Boreas Pass Auto Tour Iron Rails: from Bust to Rust

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Summit ACP FINAL Report.Pdf

CO 9 SOUTH SUMMIT ACCESS STUDY SUMMIT COUNTY LINE (MP 77.49) TO BOREAS PASS RD (MP 86.26) DEC 2020 South Summit Colorado State Highway 9 Access and Conceptual Trail Design Study SOUTH SUMMIT COLORADO STATE HIGHWAY 9 ACCESS AND CONCEPTUAL TRAIL DESIGN STUDY CO-9: M.P. 77.49 (Carroll Lane) to M.P. 86.26 (Broken Lance Drive/Boreas Pass Road) CDOT Project Code 22621 December 2020 Prepared for: Summit County 208 Lincoln Avenue Breckenridge, CO 80424 Bentley Henderson, Assistant Manager Town of Blue River 0110 Whispering Pines Circle Blue River, CO 80424 Michelle Eddy, Town Manager Town of Breckenridge 150 Ski Hill Road Breckenridge, CO 80424 Rick Holman, Town Manager Colorado Department of Transportation Region 3 – Traffic and Safety 222 South 6th Street, Room 100 Grand Junction, Colorado 81501 Brian Killian, Permit Unit Manager Prepared by: Stolfus & Associates, Inc. 5690 DTC Boulevard, Suite 330W Greenwood Village, Colorado 80111 Michelle Hansen, P.E., Project Manager SAI Reference No. 1000.005.10, 4000.031, 4000.035, 4000.036 Stolfus & Associates, Inc. South Summit Colorado State Highway 9 Access and Conceptual Trail Design Study TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... i 1.0 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Study Background ............................................................................................. 1 1.2 Study Coordination .......................................................................................... -

Technical Memorandum

Analysis and Technical Update to the Colorado Water Plan Technical Memorandum Prepared for: Colorado Water Conservation Board Project Title: Current and 2050 Planning Scenario Water Supply and Gap Results Date: September 18, 2019 Prepared by: Wilson Water Group Reviewed by: Jacobs, Brown & Caldwell Technical Update Water Supply and Gap Results Table of Contents Section 1 : Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 10 Section 2 : Definitions and Terminology ........................................................................................................ 11 Section 3 : SWSI 2010 Water Supply Methodology....................................................................................... 12 Section 4 : Technical Update Water Supply Methodology ............................................................................ 15 4.1 Current/Baseline Water Supply Methodology .......................................................................... 15 4.1.1 CDSS Basin Water Supply Methodology ..................................................................................... 16 4.1.2 Non-CDSS Basin Water Supply Methodology ............................................................................. 19 4.2 Planning Scenario A-E Water Supply Methodology .................................................................. 21 4.2.1 Planning Scenario Water Supply Adjustments ........................................................................... -

Overview of the Colorado Division of Water Resources

Colorado Division of Water Resources Water Literate Leaders of Northern Colorado • October 02, 2019 • Corey DeAngelis, Division Engineer • Mark Simpson, Poudre Water Commissioner • Jean Lever, Thompson Water Commissioner • Water Resources • Water • Parks and Wildlife Conservation Board • Oil & Gas • Reclamation, Conservation Mining and Safety Commission • State Land Board • Avalanche Information Center • Forestry https://cdnr.us/ • The position of Water Commissioner was created by the Legislature in 1879 • The office of State Hydraulic Engineer was created by the Legislature in 1881 • State Engineer is Governor Appointed • State Engineer’s Office became part of DNR in 1969 www.water.state.co.us Division of Water Resources Roles and Responsibilities • Water Administration – Surface & Underground – Water Court Participation • Interstate Compacts and Decrees • Flow Measurement (Hydrographic Program) • Public Safety (Dams and Wells) • Water Well Permitting • Public Information Service/Record Keeping DWR Water Divisions & Offices Division 1 Water Districts Map South Platte Basin Hydrology • USGS estimates total basin native flows to average about 1,400,000 acre-feet annually • Transmountain water imports average about 400,000 acre-feet annually • Total annual surface water diversions average about 4,000,000 acre-feet annually TRANSMOUNTAIN DIVERSIONS OFFICE OF THE STATE ENGINEER 1 2 3 STEAMBOAT 4 6 SPRINGS 5 6 7 30 8 TO COLORADO RIVER BASIN 31 GREELEY SOUTH 30. SARVIS DITCH 32 TO SOUTH PLATTE BASIN 31. STILLWATER DITCH 1. WILSON SUPPLY DITCH 32. DOME DITCH 9 2. DEADMAN DITCH 3. LARAMIE POUDRE TUNNEL 1 4. SKYLINE DITCH 5. CAMERON PASS DITCH 10 6. MICHIGAN DITCH 11 DENVER 7. GRAND RIVER DITCH 5 17 16 15 8. -

Wildfire Planning Indiana Creek Watershed Breckenridge, Colorado

Wildfire Planning Indiana Creek Watershed Breckenridge, Colorado Prepared for: The Town of Breckenridge P.O. Box 168 Breckenridge, CO 80424 Prepared by: 130 Ski Hill Road, Suite 100 Breckenridge, CO 80424 October 2015 Wildfire Planning Indiana Creek Watershed Breckenridge, Colorado Prepared for: The Town of Breckenridge P.O. Box 168 Breckenridge, CO 80424 Prepared by: 130 Ski Hill Road, Suite 100 Breckenridge, CO 80424 October 2015 Cover photograph: Goose Pasture Tarn and Indiana Creek watershed top left, Hayman watershed lower right Wildfire Planning: Indiana Creek Watershed Breckenridge, Colorado Wildfire Planning: Indiana Creek Watershed Breckenridge, Colorado Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Report Organization ...................................................................................................................... 1 Watershed and Geomorphic Characteristics of Indiana Creek ............................................................. 3 2.1 Water-quality Impacts from Wildfire............................................................................................ 3 2.2 Watershed Characteristics ............................................................................................................. 5 2.3 Hydrologic Impacts ...................................................................................................................... -

Trails Plan | 2009 Town of Breckenridge | Trails Plan

TOWN OF BRECKENRIDGE | TRAILS PLAN | 2009 TOWN OF BRECKENRIDGE | TRAILS PLAN TOWN OF BRECKENRIDGE TRAILS PLAN Introduction 4 Plan Philosophy 4 Plan Prioritization 5 Plan Goals and Objectives 5 Role of the Plan 5 Plan Assumptions 6 Plan Implementation 6 Plan Organization 6 How This PlanW as Developed 6 Winter and Summer Elements 7 Disclaimer 7 Planning Areas 7 Area 1: Ski Hill Road/Peak 7/8 Base Area 7 Peaks Trailhead and Trails 7 Freeride Park 8 Shock Hill/Nordic Center 8 Cucumber Gulch Preserve 9 Claimjumper/Recreation Center Connection 9 Peak 7 Neighborhood Connection 10 New Nordic World/Peak 6 Expansion 10 Iowa Hill Trailhead 10 American Way Access 10 Area 2: Core/Upper Four Seasons Area 11 Riverwalk Connection 11 Klack Placer 11 The Cedars/Trails End Connection 11 F&D Placer to Burro Connection 12 Maggie Pond Access 12 Four O’Clock Ski Run 12 Timber Trail 12 Maggie Placer Trail 13 Area 3: Breckenridge South 13 Aspen Grove/Aspen Alley Trail 13 Wakefield Trailhead 13 Little Mountain 13 Blue River/Hoosier Pass Recpath 14 The Burro Trail Accesses 14 Bekkedal/Gold King (lots 1&2) to Burro Connection 14 Ski Area Equestrian Trails 14 Now Colorado/Silver Queen Connection 15 Riverwood Trail 15 PAGE 1 TRAILS PLAN | TOWN OF BRECKENRIDGE TOWN OF BRECKENRIDGE | TRAILS PLAN Area 3: Breckenridge South (continued) Breckenridge Park Estates Trailhead 15 Fredonia Gulch Trailhead 16 Bemrose Ski Circus 16 Wheeler Trail Resurrection 16 Pennsylvania Gulch and Indiana Creek Road Winter Access 16 Spruce Creek Trail Spur 16 Lehman Gulch Trail 17 Monte Cristo -

Denver, South Park & Pacific Railroad

Denver Public Library, Western History Department. History Western Library, Public Denver W.H. Rau, publisher, from C.S. Ryland Collection. Ryland C.S. from publisher, Rau, W.H. pulls away from the Nathrop Station, by Joseph Collier, courtesy of the the of courtesy Collier, Joseph by Station, Nathrop the from away pulls 1880’s. late the in Canon Platte lower of defile A passenger and cargo train of the Denver, South Park & Pacific Railroad Railroad Pacific & Park South Denver, the of train cargo and passenger A Denver South Park & Pacific 112 threads the narrow narrow the threads 112 Pacific & Park South Denver the original dream was never fully realized. realized. fully never was dream original the railroad system wholly contained within the state, state, the within contained wholly system railroad and the DSP&P became the largest narrow gauge gauge narrow largest the became DSP&P the and Although 335 miles of track were eventually laid laid eventually were track of miles 335 Although South Park & Pacific Railway Company in 1872. 1872. in Company Railway Pacific & Park South Denver’s leading businessmen formed The Denver Denver The formed businessmen leading Denver’s would outweigh the costs, Evans and a group of of group a and Evans costs, the outweigh would the challenge and convinced that the benefits benefits the that convinced and challenge the to achieve a functional rail line. Still undaunted by by undaunted Still line. rail functional a achieve to would require tunneling through tons of solid rock rock solid of tons through tunneling require would Excessive grades and treacherous winter weather weather winter treacherous and grades Excessive wagon roads and even foot trails seemed unlikely. -

Ipomopsis Globularis (Brand) W.A

Ipomopsis globularis (Brand) W.A. Weber (Hoosier Pass ipomopsis): A Technical Conservation Assessment Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Species Conservation Project March 15, 2005 Susan Spackman Panjabi and David G. Anderson Colorado Natural Heritage Program 8002 Campus Delivery — Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO 80523 Peer Review Administered by Center for Plant Conservation Panjabi, S.S. and D.G. Anderson (2005, March 15). Ipomopsis globularis (Brand) W.A. Weber (Hoosier Pass ipomopsis): a technical conservation assessment. [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/ipomopsisglobularis.pdf [date of access]. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This research was facilitated by the helpfulness and generosity of many experts, particularly Dr. Barry Johnston, William Jennings, Tim Hogan, Loraine Yeatts, Dr. Ron Hartman, and Dr. J. Mark Porter. Their interest in the project and time spent answering questions were extremely valuable, and their insights into the distribution, habitat, taxonomy, and ecology of Ipomopsis globularis were crucial to this project. Thanks also to Greg Hayward, Gary Patton, Jim Maxwell, Andy Kratz, and Joy Bartlett for assisting with questions and project management. Jane Nusbaum and Barbara Brayfield provided crucial financial oversight. Dr. J. Mark Porter provided critical literature on the taxonomic relationships within the genus Ipomopsis. Loraine Yeatts, Tim Hogan, Ron Abbott, Nancy Redner, Benjamin Madsen, and Kim Regier provided valuable insights based on their experiences with I. globularis. Sara Mayben and Benjamin Madsen provided information specific to the South Park Ranger District of the Pike- San Isabel National Forest. Gary Nichols offered insight regarding land use activities in Park County. -

A Historical View: Transmount Ain Diversion Development in Colorado

A HISTORICAL VIEW: TRANSMOUNT AIN DIVERSION DEVELOPMENT IN COLORADO John N. Winchester, P.E.' ABSTRACT As the headwaters for seven major rivers, water resources in Colorado have been diverted for use for over ISO years. Transbasin diversions have been developed to move water from one river basin to another, including transmountain diversions, which move water over the continental divide. Transmountain diversions have historically been developed to provide water for irrigated agriculture and municipal purposes. This paper briefly discusses the development of each of Colorado's 30 transmountain diversions between the Colorado, South Platte, Arkansas and Rio Grande river basins, and provides a summary of diversions for recent years. INTRODUCTION Many people in the Colorado water community have traditionally divided transbasin diversions into two categories: transmountain diversions, which move water from one side of the continental divide to the other, and transbasin, where water is moved between basins that ultimately drain to the same ocean. In addition to surface water diversions, there are also geological formations that allow wells located in one basin to pump water native to another. BACKGROUND Based on the 2000 Census and the Colorado State Engineer's records, the front range of Colorado (the east slope, excluding the North Platte and Rio Grande basins) has 89% of the state's population but only 16% of the state's water (USCB, 2000; SE~, 2000). Because the front range and the eastern plains of Colorado are in a semi-arid environment, transmountain diversions, diversions from one side of the continental divide to the other, have been constructed to move water to the eastern slope to help satisfy the region's demand for water. -

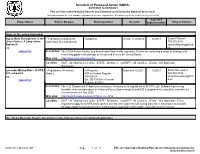

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA)

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2021 to 06/30/2021 Pike and San Isabel National Forests and Cimarron and Comanche National Grasslands This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring Nationwide Gypsy Moth Management in the - Vegetation management Completed Actual: 11/28/2012 01/2013 Susan Ellsworth United States: A Cooperative (other than forest products) 775-355-5313 Approach [email protected]. EIS us *UPDATED* Description: The USDA Forest Service and Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service are analyzing a range of strategies for controlling gypsy moth damage to forests and trees in the United States. Web Link: http://www.na.fs.fed.us/wv/eis/ Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Nationwide. Locatable Mining Rule - 36 CFR - Regulations, Directives, In Progress: Expected:12/2021 12/2021 Sarah Shoemaker 228, subpart A. Orders NOI in Federal Register 907-586-7886 EIS 09/13/2018 [email protected] d.us *UPDATED* Est. DEIS NOA in Federal Register 03/2021 Description: The U.S. Department of Agriculture proposes revisions to its regulations at 36 CFR 228, Subpart A governing locatable minerals operations on National Forest System lands.A draft EIS & proposed rule should be available for review/comment in late 2020 Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=57214 Location: UNIT - All Districts-level Units. STATE - All States. COUNTY - All Counties. LEGAL - Not Applicable. -

Major Water Transfers Between Basins

Major Water Transfers Between Basins Michael Sullivan Colorado Division of Water Resources Flood Update High Velocity Flows Moving Big Rocks Colorado’s Major Basins and Subbasins Green Laramie North Yampa Platte White South Platte and Republican Colorado Gunnison San Miguel Arkansas Dolores Rio Grande Mancos San Juan La Plata Conejos TRANSMOUNTAIN DIVERSIONS OFFICE OF THE STATE ENGINEER 1 2 3 R VE 4 RI STEAMBOAT 5 7 YA 6 SPRINGS 6 MPA R 8 IV E ER T T 9 A L P 41 TO COLORADO RIVER BASIN 10 SOUTH 40. DIVIDE HIGHLINE FEEDER DITCH 42 GREELEY 41. SARVIS DITCH 43 TO SOUTH PLATTE BASIN 42. STILLWATER DITCH 43. DOME DITCH 1. WILSON SUPPLY DITCH 44. REDLANDS POWER CANAL 11 2. DEADMAN DITCH 1 3. BOB CREEK DITCH 4. COLUMBINE DITCH 13 12 5. LARAMIE POUDRE TUNNEL 6. SKYLINE DITCH 14 DENVER 7. CAMERON PASS DITCH 5 20 19 18 IVER 22 21 8. MICHIGAN DITCH O R GLENWOOD RAD 9. GRAND RIVER DITCH OLO SPRINGS C 15 10. ALVA B. ADAMS TUNNEL 23 11. MOFFAT WATER TUNNEL GRAND JUNCTION 39 16 12. BERTHOUD PASS DITCH 17 13. STRAIGHT CREEK TUNNEL 40 24 14. VIDLER TUNNEL 15. HAROLD D. ROBERTS TUNNEL 16. BOREAS PASS DITCH 44 17. HOOSIER PASS TUNNEL R DELTA 4 E IV 2 R TO GUNNISON RIVER BASIN 25 ON 36. RED MOUNTAIN DITCH GUNNIS 37. CARBON LAKE DITCH PUEBLO TO ARKANSAS BASIN A 38. MINERAL POINT DITCH MONTROSE RKA 18. COLUMBINE DITCH NSA 39. LEON TUNNEL S R 19. EWING DITCH IVE R 20. WURTZ DITCH D 28 21. -

G for Licenses Guaranteed to Hunters Due to Natural Disaster Relief + Number

AS APPROVED – 01/13/2021 FINAL REGULATIONS - CHAPTER W-0 - GENERAL PROVISIONS ARTICLE II - LICENSE TYPES AND REQUIREMENTS #001 - Hunt Codes A. Hunt Codes are a series of eight sequential letters and numbers which denote the species, sex of animal, unit number, season, and hunt type for each choice shown on the application: 1. Species - The first character of the hunt code is a letter denoting species: A for pronghorn B for black bear C for desert bighorn sheep D for deer E for elk G for mountain goat H for small game or furbearer L for mountain lion M for moose P for greater prairie-chicken S for rocky mountain bighorn sheep T for wild turkey 2. Sex of Animal - The second character of the hunt code is a letter denoting the sex of the animal for which the license is valid: E for either-sex (antlerless or antlered) of animal, as defined in #200 F for antlerless or doe animals, as defined in #200 M for antlered or buck animals, as defined in #200 3. Unit Number - The third through fifth characters are numbers denoting the unit or group of units in which the license is valid. Units are numbered sequentially beginning with the number 1. Zeros appear before the unit number when it is less than three characters in length, i.e. 001, 023, etc. Where the license is valid in more than one unit, the lowest numbered complete unit in the group is used, and the season table shows the complete list of valid units or portions thereof. -

Design Narrative

Fremont Recpath Summit County Extension Design Narrative Section 5 Alternatives 62 Fremont Recpath Summit County Extension Design Narrative 5.0 Summit County Extension: Alternatives The Summit County Extension: Design Narrative describes the action alternatives for connecting the Tenmile Canyon Recpath at Copper Mountain to the terminus of the Climax segment of the pathway at the northern boundary of the Climax property, as well as alternative routes explored in the field that were reviewed but not advanced for further study due to environmental, physical, or budgetary constraints, or reviewed but not considered to be feasible or constructible. 5.1 Alternative 1: No Action Under the No Action Alternative, no development of a separated Pathway or expansion of the roadway surface to better accommodate bicycle travel would be pursued over Fremont Pass. The Bicycle Level of Service would remain extremely low, and the local, regional, and statewide goals for improved intermodal connectivity of the Summit and Lake County Bicycle Pathway Systems would remain unsatisfied. Photo Plate 50 Existing condition Lack of shoulder width to accommodate safe shared use of the road surface 63 Fremont Recpath Summit County Extension Design Narrative 5.2 Action Alternative 2: Historic Rail Grade Alignment (Preferred Alternative) Preliminary pathway layout considerations have prioritized following an alignment that overlays the historic route of the Highline Extension of the Denver, South Park and Pacific Railroad. 5.2.1 Historic Context: DSP&P Highline Extension Map 4 Historic Rail Lines: Fremont Pass The preferred alignment for the Summit County Extension of the Fremont Recpath follows the rail bed of the historic High Line Extension of the Denver South Park and Pacific Railroad (DSP&P).