1. Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Census Handbook, Anantapur

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 SERIES 2 ANDHRA PRADESH DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK ANANTAPUR PARTS XIII-A & B VILLAGE & TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE & TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS· ABSTRACT S. S. JAYA RAO OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS ANDHRA PRADESH PUBLISHED BY THE GOVERNMENT OF ANDHRA PRADESH .1986 SRI KRISHNADEVARA YA UNIVERSITY, ANANTAPUR The motif given on the cover page is the Library Building representing Sri Krishnadevaraya University, Anantapur. Land of Diamonds and Great Empires, Rayalaseema, heir to a very rich and varied cultural heritage, now proudly advances to a new milestone in her progress when the new University was inaugurated on the 22nd November, 1981. True to the legacy of the golden era, the new University is named after SRI KRISHNADEVARAYA, the greatest of the Vijayanagara Rulers. The formation of Sri Krishnadevaraya University fulfils the long cherished dreams and aspirations of the students, academicians, educationists and the general public of the region. The new University originated through the establishment of a Post-Graduate Centre at Anantapur which was commissioned in 1968 with the Departments of Telugu, English, Mathematics, Chemistry and Physics with a strength of 60 students and 26 faculty members. It took its umbrage in the local Government Arts Col/ege, Anantapur as an affiliate to the Sri Venkateswara University. In 1971, the Post-Graduate Centle moved into its own campus at a distance of 11 Kilometers from Anantapur City on the Madras Highway in an area of 243 hectares. The campus then had just two blocks, housing Physical Sciences and Humanities with a few quarters for the staff and a hostel for the boys. -

The Mapping of Geological Features of Narpala Mandal, Anantapur District, AP, India Using Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques ˆpradeep Kumar

The International journal of analytical and experimental modal analysis ISSN NO:0886-9367 The Mapping of Geological Features of Narpala Mandal, Anantapur District, AP, India Using Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques ˆPradeep Kumar. B1, Raghu Babu. K1*, Krupavathi. C1, Rajasekhar. M1, Siva Kumar Reddy. P1, Ramachandra. M1, Narayana Swamy. B1, Ravi Kumar. P1 1Department of Geology, Yogi Vemana University, Kadapa, Andhra Pradesh, India. *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract - Good geological maps are essential not only for exploration and exploitation of natural resources but also for a variety of other purposes such as location of dams, tunneling, power plants, alignment of highway lines etc. even in areas where geological mapping has been done in great detail, Remote Sensing (RS) techniques have contributed information to unknown such as identification of new faults and fractures. More or less all-digital, topographic mapping and most mapping projects required the digital maps prepared by using RS and Geographical Information System (GIS) techniques with geospatial database. In this paper we have prepared Geology, Geomorphology, Lineament, Lineament density, Slope and Land Use/Land Cover maps by using RS and GIS techniques. For preparing this maps various LANDSAT data and DEM data have been collected and processed by various techniques adopted and using ERDAS and GIS software’s. Keywords: Geological, Exploration, Topographic, Structural mapping, Land Use/Land Cover. 1. Introduction The most understandable usage of geological map is to indicate the nature of the near – surface bedrock. This is obviously of great importance to civil engineers recommended by the geologist to guide on the excavation of road cuttings or on the siting of bridges, to geographers studying the use of land and to companies exploring minerals. -

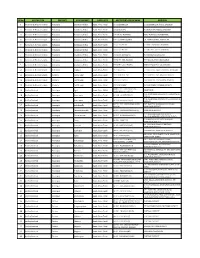

Sl.No. STATES/UTS DISTRICT SUB DISTRICT CATEGORY REPORTING UNITS NAME ADDRESS

Sl.No. STATES/UTS DISTRICT SUB DISTRICT CATEGORY REPORTING UNITS NAME ADDRESS 1 Andaman & Nicobar Islands Andamans Andamans Urban Stand Alone-Fixed ICTC BAMBOOFLAT CHC BAMBOOFLAT, SOUTH ANDAMAN 2 Andaman & Nicobar Islands Andamans Andamans Urban Stand Alone-Fixed ICTC BARATANG PHC BARATANG MIDDLE ANDAMAN 3 Andaman & Nicobar Islands Andamans Andamans Urban Stand Alone-Fixed ICTC DR. R.P HOSPITAL DR.R.P HOSPITAL, MAYABUNDER. 4 Andaman & Nicobar Islands Andamans Andamans Urban Stand Alone-Fixed ICTC G.B.PANT HOSPITAL G.B. PANT HOSPITAL, PORT BLAIR 5 Andaman & Nicobar Islands Andamans Andamans Urban Stand Alone-Fixed ICTC,CHC RANGAT CHC RANGAT,MIDDLE ANDAMAN 6 Andaman & Nicobar Islands Andamans Andamans Urban Stand Alone-Fixed ICTC,PHC HUT BAY PHC HUT BAY, LITTLE ANDAMAN 7 Andaman & Nicobar Islands Andamans Andamans Urban Stand Alone-Fixed ICTCS, PHC HAVELOCK PHC HAVELOCK, HAVELOCK 8 Andaman & Nicobar Islands Andamans Andamans Urban Stand Alone-Fixed ICTCS, PHC NEIL ISLANDS PHC NEIL ISLANDS, NEIL ISLANDS 9 Andaman & Nicobar Islands Andamans Andamans Urban Stand Alone-Fixed ICTCS,PHC GARACHARMA, DISTRICT HOSPITAL GARACHARMA 10 Andaman & Nicobar Islands Andamans Diglipur Stand Alone-Fixed ICTC DIGLIPUR CHC DIGLIPUR , NORTH & MIDDLE ANDAMAN 11 Andaman & Nicobar Islands Nicobars Car Nicobar Stand Alone-Fixed ICTC CAMPBELL BAY PHC CAMPBELL BAY, NICOBAR DISTRICT 12 Andaman & Nicobar Islands Nicobars Car Nicobar Stand Alone-Fixed ICTC CAR NICOBAR B.J.R HOSPITAL, CAR NICOBAR,NICOBAR 13 Andaman & Nicobar Islands Nicobars Car Nicobar Stand Alone-Fixed -

PROFILE of ANANTAPUR DISTRICT the Effective Functioning of Any Institution Largely Depends on The

PROFILE OF ANANTAPUR DISTRICT The effective functioning of any institution largely depends on the socio-economic environment in which it is functioning. It is especially true in case of institutions which are functioning for the development of rural areas. Hence, an attempt is made here to present a socio economic profile of Anantapur district, which happens to be one of the areas of operation of DRDA under study. Profile of Anantapur District Anantapur offers some vivid glimpses of the pre-historic past. It is generally held that the place got its name from 'Anantasagaram', a big tank, which means ‘Endless Ocean’. The villages of Anantasagaram and Bukkarayasamudram were constructed by Chilkkavodeya, the Minister of Bukka-I, a Vijayanagar ruler. Some authorities assert that Anantasagaram was named after Bukka's queen, while some contend that it must have been known after Anantarasa Chikkavodeya himself, as Bukka had no queen by that name. Anantapur is familiarly known as ‘Hande Anantapuram’. 'Hande' means chief of the Vijayanagar period. Anantapur and a few other places were gifted by the Vijayanagar rulers to Hanumappa Naidu of the Hande family. The place subsequently came under the Qutub Shahis, Mughals, and the Nawabs of Kadapa, although the Hande chiefs continued to rule as their subordinates. It was occupied by the Palegar of Bellary during the time of Ramappa but was eventually won back by 136 his son, Siddappa. Morari Rao Ghorpade attacked Anantapur in 1757. Though the army resisted for some time, Siddappa ultimately bought off the enemy for Rs.50, 000. Anantapur then came into the possession of Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan. -

Dolomite Mineral Occurrence in Narpala Mandal in Ananthapuramu District, Andhra Pradesh, South India

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 8, ISSUE 12, DECEMBER 2019 ISSN 2277-8616 Dolomite Mineral Occurrence In Narpala Mandal In Ananthapuramu District, Andhra Pradesh, South India. T.Madhu, B.Narayana swamy, U.Imran Basha, M.Rajasekhar Abstract: Dolomite is a carbonate rock that in its pure form consists essentially of a double carbonate corresponding to CaMg (CO3)2. Dolomite is applied to a carbonate rock in which at least the minimum amount of 41 percent magnesium carbonate is present. Dolomite closely resembles limestone, but close inspection shows many differences between them. Replacement of calcium in limestone by magnesium results in the recrystallization of the limestone to form dolomite. This replacement process, called dolomitization, generally tends to destroy the original or earlier texture and structure of the rock. Complete recrystallization produces a rock in which many dolomite crystals are well outlined. In general, dolomite is more even grained and less fine grained than limestone. The weathered surface of dolomite commonly is mottled and shows the outlines of dolomitic grains and generally shows the extent of dolomitization. Factors governing the kind of materials found in limestone also apply to dolomite. Dharwar Super group, peninsular gneissic Complex-II and Cuddapah Super group. Small exposures of Meta basalt representing Kadiri Schist Belt and amphibolites representing Ramagiri Schist Belt are found in south east corner and west central part of the toposheets respectively. Western part of the toposheet is covered by rocks of PGC-II and is intruded by dolerite dykes and quartz veins. Conglomerate, dolomite, quartzite and shale belonging to Cuddapah Super group is exposed successively towards east. -

Irrigation Profile Anathapuram

10/31/2018 District Irrigation Profiles IRRIGATION PROFILE OF ANANTAPURAMU DISTRICT *Click here for Ayacut Map INTRODUCTION Ananthapuramu District is situated in Rayalseema region of Andhra Pradesh state and lies between 13°-40'N to 15°-15'N Latitude and 76°-50'E to 78°-30'E Longitude with a population of 40,83,315 (2011 census). One of the famous spiritual center in this district is Puttaparthi and it is 80Km. away from Ananthapuramu. The District falls partly in Krishna basin and partly in Pennar basin. The District is surrounded by Bellary, Kurnool Districts on the North, Kadapa and Kolar Districts of Karnataka on South East and North respectively. The district is principally a hot country and temperatures vary from 17°C-40°C. The important rivers flowing in the District are (1) Pennar (2) Jayamangali (3) Chitravathi (4) Vedavathi (also called Hagari), (5) Papagni, (6) Maddileru. The district head quarter is connected by S.C. Railways broad gauge railway line from Secunderabad, Guntakal, Bangalore and Bellary (Via) Guntakal to Pakala. Most of the area in this District is covered under Minor Irrigation Sources only in addition to one completed Major Irrigation Project viz., Tungabhadra Project High level canal (TBP HLC) system stage-I (A joint venture of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh States). The Right Bank High level canal (R.B.H.L.C.) takes off from right bank of T.B. Dam and runs in Karnataka and enters in Andhra Pradesh at Km. 105.437 and contemplated to irrigate an ayacut of 2.849 Lakh acres out of this 1,45,236 acres in Ananthapuramu district and remaining is Kurnool and Kadapa District. -

Penukonda Assembly Andhra Pradesh Factbook | Key Electoral Data of Penukonda Assembly Constituency | Sample Book

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.electionsinindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/AP-158-0118 ISBN : 978-93-87415-92-8 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 166 for the use of this publication. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency at a Glance | Features of Assembly as per 1-2 Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps 2 Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency in District | Boundaries 3-9 of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary Constituency | Town & Village-wise Winner Parties- 2014-PE, 2014-AE, 2009-PE and 2009-AE Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 10-16 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population | Towns and Villages by 17-18 Population Size | Sex Ratio -

Ground Water Brochure Anantapur District, Andhra Pradesh

For Official Use Only CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GROUND WATER BROCHURE ANANTAPUR DISTRICT, ANDHRA PRADESH SOUTHERN REGION HYDERABAD September 2013 CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GROUND WATER BROCHURE ANANTAPUR DISTRICT, ANDHRA PRADESH (AAP- 2012-13) By V.VINAY VIDYADHAR, ASSISTANT HYDROGEOLOGIST SOUTHERN REGION BHUJAL BHAWAN, GSI Post, Bandlaguda NH.IV, FARIDABAD -121001 Hyderabad-500068 HARYANA, INDIA Andhra Pradesh Tel: 0129-2418518 Tel: 040-24225201 Gram: Bhumijal Gram: Antarjal GROUND WATER BROCHURE ANANTAPUR DISTRICT, ANDHRA PRADESH CONTENTS S.No CHAPTER District at a Glance 1 Introduction 2 Rainfall & Climate 3 Geomorphology & Soil Types 4 Geology 5 Hydrogeology & Ground Water Scenario 6 Ground Water Resources 7 Ground Water Quality 8 Ground Water Development 9 Ground Water Related Issues and Problems 10 Conclusions DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 1. GENERAL North Latitude: 13° 40’ 16°15’ Location East Longitude 70° 50’ 78°38’ Geographical area (sq.km) 19,197 Headquarters Anantapur No. of revenue mandals 65 No. of revenue villages 964 Population (2011) Total 4083315 Population density (persons/sq.km) 213 Work force Cultivators 4,85,056 Agricultural labour 4,62,292 Major rivers Pennar, Papagni Maddileru, Tadikaluru Naravanka Soils Red sandy soil, Mixed red and black soil Agroclimatic zone Scarce Rainfall zone and 2. RAINFALL Normal annual rainfall Total 535 mm Southwest monsoon 316 mm Northeast monsoon 146 mm Summer 72 mm Cumulative departure from - 31% 3. LAND USE (2012) (Area in ha) Forest 196978 Barren and uncultivated 167469 Cultivable waste 48856 Current fallows 85754 Net area sown 1049255 4. -

Handbook of Statistics Ananthapuramu District 2016

HAND BOOK OF STATISTICS ANANTHAPURAMU DISTRICT 2016 Compiled and Published by CHIEF PLANNING OFFICER ANANTHAPURAMU DISTRICT OFFICERS AND STAFF ASSOCIATED WITH THE PUBLICATION Sri Ch. Vasudeva Rao : Chief Planning Officer Smt. P. SeshaSri : Dy.Director Sri J. Nagi Reddy : Asst. Director Sri S. Sreenivasulu : Statistical Officer Sri T.Ramadasulu : Dy.Statistical Officer, I/c C. Rama Shankaraiah : Data Entry Operator INDEX TABLE NO. CONTENTS PAGE NO. GENERAL A SALIENT FEATURES OF ANANTHAPURAMU DISTRICT B COMPARISON OF THE DISTRICT WITH THE STATE C ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISONS IN THE DISTRICT D PUBLIC REPRESENTATIVES/NON OFFICIALS E PROFILE OF ASSEMBLY / PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCY 1 - POPULATION 1.1 VARIATION IN POPULATION OF - 1901 TO 2011 1.2 POPULATION STATISTICS SUMMERY-Census 2001- 2011 TOTAL NO.OF VILLAGES, HMLETS, HOUSEHOLDS, 1.3 AREA,POPULATION,DENSITY OF POPULATION AND SEX RATIO, MANDAL-WISE-Census 2011 RURAL AND URBAN POPULATION , MANDAL - WISE, 1.4 2011 CENSUS 1.5 POPULATION OF TOWNS AND CITIES - 2011 1.6 LITERACY, MANDAL - WISE, 2011 SCHEDULED CASTE POPULATION AND LITERACY RATE - CENSUS 1.7 2011 SCHEDULED TRIBES POPULATION AND LITERACY RATE - CENSUS 1.8 2011 DISTRIBUTION OF POPULATION BY WORKERS AND NON WORKERS - 1.9 MANDAL WISE 2011 CLASSIFICATION OF VILLAGES ACCORDING TO POPULATION SIZE, 1.10 MANDAL - WISE, 2011 HOUSELESS AND INSTITUTIONAL POPULATION, MANDAL-WISE- 1.11 CENSUS 2011 DISTRIBUTION OF PERSONS ACCORDING TO DIFFERENT AGE 1.12 GROUPS, 2011 CENSUS 1.13 RELEGION WISE MANDAL POPULATION - CENSUS 2011 2- MEDICAL AND PUBLIC HEALTH 2.1 GOVT.,MEDICAL FACILITIES FOR 2015-16 GOVERNMENT MEDICAL FACILITIES (ALLOPATHIC) MANDAL- 2.2 WISE(E.S.I.Particulars included), 2015-16 GOVT.,MEDICAL FACILITIES( INDIAN MEDICINE ), MANDAL-WISE - 2.3 2015-16 2.4 FAMILY WELFARE ACHIEVEMENTS DURING (2015-16) 3 - CLIMATE 3.1 MAXIMUM & MINIMUM TEMPERATURE (2015 & 2016) DISTRICT AVERAGE RAINFALL, SEASON-WISE AND MONTH WISE - 3.2 (2009-10 to 2015-16) 3.3 ANNUAL RAINFALL,STATION WISE, (2011-12 to 2015-16) TABLE NO. -

Sanctioned School Assistant Posts (New) First Secon Sl

For Latest updates, GOs RCs Please logon to www.teachersteam.tk ANNEXURE -I DIRECTOR, RMSA Letter to C & DSE No. 714/RMSA , Dated :15-1-2012 RMSA- Sanctioned School Assistant Posts (New) First Secon Sl. District School code & Name Management Langu d Total Bio Phy No. Eng Social MATHS medium age Lang. 1 Srikakulam 0101601 - ZPHS NARSIPURAM GORA Zilla Parishad TE 1 1 2 Srikakulam 0101602 - ZPHS KAMBARA VALASA Zilla Parishad TE 1 1 2 3 Srikakulam 0101603 - ZPHS VEERAGHATTAM Zilla Parishad TE 1 1 4 Srikakulam 0101604 - ZPHS KATHULAKAVITI Zilla Parishad TE 1 1 2 5 Srikakulam 0101605 - ZPHS VANDUVA Zilla Parishad TE 1 1 2 6 Srikakulam 0101607 - ZPHS TETTANGI Zilla Parishad TE 1 1 2 7 Srikakulam 0101608 - ZPHS NEELANAGARAM Zilla Parishad TE 1 1 2 8 Srikakulam 0101609 - ZPHS TALAVARAM Zilla Parishad TE 1 1 2 9 Srikakulam 0101613 - ZPHS VEERAGHATTAM (GIRLS) Zilla Parishad TE 1 1 2 10 Srikakulam 0102601 - ZPHS V.K.GUMADA Zilla Parishad TE 1 1 2 11 Srikakulam 0102602 - ZPHS M.S.PURAM Zilla Parishad TE 1 1 12 Srikakulam 0102603 - ZPHS KOPPARA Zilla Parishad TE 1 1 13 Srikakulam 0102604 - ZPHS VANGARA Zilla Parishad TE 1 1 2 14 Srikakulam 0102605 - ZPHS MARUVADA Zilla Parishad TE 1 1 15 Srikakulam 0102606 - ZPHS KONANGIPADU Zilla Parishad TE 1 1 2 16 Srikakulam 0102607 - ZPHS ARASADA Zilla Parishad TE 1 1 2 17 Srikakulam 0103601 - ZPHS KANDISA Zilla Parishad TE 1 1 2 18 Srikakulam 0103602 - ZPHS REGADI Zilla Parishad TE 1 1 2 19 Srikakulam 0103603 - ZPHS SANKILI Zilla Parishad TE 1 1 20 Srikakulam 0103604 - ZPHS DEVUDALA Zilla Parishad TE 1 1 21 Srikakulam -

GOVERNMENT of ANDHRA PRADESH ABSTRACT Agriculture

GOVERNMENT OF ANDHRA PRADESH ABSTRACT Agriculture Department – Restructured Weather Based Crop Insurance Scheme (R.W.B.C.I.S)- Kharif, 2018 – Implementation of RWBCIS - Notification of Cluster/ District wise Crops - Orders – Issued. __________________________________________________________________________________ AGRICULTURE & COOPERATION (AGRI.II) DEPARTMENT G.O.MS.No. 54 Dated: 17-05-2018 Read the following: 1. G.O.Rt.No.305 , Agri. & Coop. (Agri.II) Dept., dated: 07.05.2018. 2. From the Special Commissioner of Agriculture, A.P., Guntur, Lr. No. Crop Ins. (2)10/2018 Dt. 15.05.2018. *** ORDER: The following Notification shall be published in the Andhra Pradesh State Extra-Ordinary Gazette dated:18.05.2018. NOTIFICATION In the G.O. first read above, Government have accorded administrative approval for implementation of Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana (PMFBY) & Restructured Weather Based Crop Insurance Scheme (RWBCIS) during Kharif, 2018 as recommended by the Financial Bid Processing Committee. 2. In the Letter second read above, the Special Commissioner of Agriculture, A.P., Guntur has requested the Government to issue NOTIFICATION orders for implementation of Restructured Weather Based Crop Insurance Scheme (RWBCIS) during Kharif 2018 season. 3. The following contents are included in the Notification. Restructured Weather Based Crop Insurance Scheme (RWBCIS) “Further, the claims under Restructured Weather Based Crop Insurance Scheme (R.W.B.C.I.S) shall be settled on the basis of the weather data furnished by the APSDPS/ State Govt. Mandal level Rain Gauge Stations/IMD Weather Stations for the notified crops & districts and not on the basis of individual declaration of crop damage Annavari Certificate/Gazette notification declaring the area Drought /Flood/ Cyclone affected etc., issued by the Government.” 4. -

District Survey Report - 2018

District Survey Report - 2018 DEPARTMENT OF MINES AND GEOLOGY Government of Andhra Pradesh DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT - ANANTAPURAMU DISTRICT Prepared by ANDHRA PRADESH SPACE APPLICATIONS CENTRE (APSAC) ITE & C Department, Govt. of Andhra Pradesh 2018 DMG, GoAP 1 District Survey Report - 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS APSAC wishes to place on record its sincere thanks to Sri. B.Sreedhar IAS, Secretary to Government (Mines) and the Director, Department of Mines and Geology, Govt. of Andhra Pradesh for entrusting the work for preparation of District Survey Reports of Andhra Pradesh. The team gratefully acknowledge the help of the Commissioner, Horticulture Department, Govt. of Andhra Pradesh and the Director, Directorate of Economics and Statistics, Planning Department, Govt. of Andhra Pradesh for providing valuable statistical data and literature. The project team is also thankful to all the Joint Directors, Deputy Directors, Assistant Directors and the staff of Mines and Geology Department for their overall support and guidance during the execution of this work. Also sincere thanks are due to the scientific staff of APSAC who has generated all the thematic maps. VICE CHAIRMAN APSAC DMG, GoAP 2 District Survey Report - 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents Page Acknowledgements List of Figures List of Tables 1 Salient Features of the District 1 1.1 Historical Background 1 1.2 Topography 1 1.3 Places of Tourist Importance 2 1.4 Rainfall and Climate 6 1.5 Winds 12 1.6 Population 13 1.7 Transportation: 14 2 Land Utilization, Forest and Slope in the District