Women in Punk Creating Queer Identity Spaces: Strategies of Resistance Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sydney Gala 29Th November 2016

SYDNEY GALA 29TH NOVEMBER 2016 Photo: Geoffrey D’Unienville Vance Joy at Austin City Limits Photo: Ashley Mar Photo Wall at “Ketchup” Logo by Daniel Lewis Photo: Carl Dziunka Heart of St Kilda Concert, Melbourne Thank you to our Board Damian Cunningham (Audience and Sector Development Director, Live Music Office) Dean Ormston (Head of Member Services, APRA AMCOS) Emma Coyle (Industry Development Manager, Music SA) Emily Collins (Executive Officer, Music NSW) Joel Edmondson (Executive Officer, Q Music) Katie Noonan (Musician) Laura Harper (Chief Executive Officer, Music Tasmania) Maggie Collins (Programmer at BIGSOUND) Mike Harris (CEO, WAM) Paris Martine (Contrary Music) Simon Collins (Music Editor, The West Australian) and all our team & volunteers! Director - Larry Heath Publicist - Nat Files Graphic & Logo Design - Daniel Lewis Video - Filip Franzoni Photo: Geoffrey D’Unienville Program Jake Stone (DJ Set) Show kicks off at 8pm with your host KLP Performance: Colin Lillie and Leah Flanagan NSW Awards Performance: LEFT. Genre Awards Performance: High VIolet Industry and Festival Awards Performance: L-FRESH THE LION Musician and Band Awards Performance: Totally Unicorn NSW AWARDS LIVE ACT OF THE YEAR LIVE MUSIC EVENT OF THE YEAR -Presented by the City of Sydney- Byron Bay Bluesfest All our Exes Live in Texas FBi SMACS Festival Boy & Bear King Street Crawl Gang of Youths Newtown Festival RUFUS Secret Garden Shining Bird THE AAA AWARD: LIVE VOICE OF THE YEAR ALL AGES AMBASSADOR David Le’aupepe (Gang of Youths) -Presented by MusicNSW- Julia Jacklin 4Elements Music Project (4EMP) Montaigne Black Wire Records Ngaiire Campbelltown Arts Centre Vera Blue Century Venues Good Life Festival VENUE OF THE YEAR -Presented by Moshtix- Civic Underground Newtown Social Club Oxford Art Factory The Chippendale Hotel The Enmore Photo: Ian Laidlaw Yours & Owls Festival, Wollongong GENRE AWARDS HIP HOP LIVE ACT OF THE YEAR ROOTS LIVE ACT OF THE YEAR^ A.B. -

Indigo FM Playlist 9.0 600 Songs, 1.5 Days, 4.76 GB

Page 1 of 11 Indigo FM Playlist 9.0 600 songs, 1.5 days, 4.76 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Trak 3:34 A A 2 Tell It Like It Is 3:08 Soul Box Aaron Neville 3 She Likes Rock 'n' Roll 3:53 Black Ice AC/DC 4 What Do You Do For Money Honey 3:35 Bonfire (Back in Black- Remastered) AC/DC 5 I Want Your Love 3:30 All Day Venus Adalita 6 Someone Like You 3:17 Adrian Duffy and the Mayo Bothers 7 Push Those Keys 3:06 Adrian Duffy and the Mayo Bothers 8 Pretty Pictures 3:34 triple j Unearthed Aela Kae 9 Dulcimer Stomp/The Other Side 4:59 Pump Aerosmith 10 Mali Cuba 5:38 Afrocubismo AfroCubism 11 Guantanamera 4:05 Afrocubismo AfroCubism 12 Weighing The Promises 3:06 You Go Your Way, I'll Go Mine Ainslie Wills 13 Just for me 3:50 Al Green 14 Don't Wanna Fight 3:53 Sound & Color Alabama Shakes 15 Ouagadougou Boogie 4:38 Abundance Alasdair Fraser 16 The Kelburn Brewer 4:59 Abundance Alasdair Fraser 17 Imagining My Man 5:51 Party Aldous Harding 18 Horizon 4:10 Party Aldous Harding 19 The Rifle 2:44 Word-Issue 46-Dec 2006 Alela Diane 20 Let's Go Out 3:11 triple j Unearthed Alex Lahey 21 You Don't Think You Like People Like Me 3:47 triple j Unearthed Alex Lahey 22 Already Home 3:32 triple j Unearthed Alex the Astronaut 23 Rockstar City 3:32 triple j Unearthed Alex the Astronaut 24 Tidal Wave 3:47 triple j Unearthed Alexander Biggs 25 On The Move To Chakino 3:19 On The Move To Chakino Alexander Tafintsev 26 Blood 4:33 Ab-Ep Ali Barter 27 Hypercolour 3:29 Ab-Ep Ali Barter 28 School's Out 3:31 The Definitive Alice Cooper Alice Cooper 29 Department Of Youth 3:20 -

October 10 2018

INAUGURAL CEREMONY October 10 2018 “I know that there are vast numbers of men who support woman and huge numbers of women who want more so together let’s create the mother of all paradigm shifts.” Jenny Morris Chrissy Amphlett PHOTOGRAPHER: TONY MOTT 2 1 “I know that there are vast numbers of men who support woman and huge numbers of women who want more so together let’s create the mother of all paradigm shifts.” Jenny Morris Chrissy Amphlett PHOTOGRAPHER: TONY MOTT 2 1 A FEW WORDS Message From AWMA Founding Director Message from the Premier & Ministers & Executive Producer It is our great pleasure to welcome you to the first Australian Women in Music Awards. VICKI GORDON We’re proud that Queensland is the inaugural home to this phenomenal program. The Queensland Government is committed to promoting the work of women in all fields, including the arts, and positions of leadership. We have pledged to appoint 50 per cent women to government boards by 2020, because we know that companies This evening we will make Australian music history. that appoint more women do better. The inaugural Australian Women in Music Awards is the result of many Australian women contribute a great deal to the country’s contemporary music industry, and yet only one in five voices and many visions coming together, all of whom refuse to allow registered songwriters and composers in our nation are women. Women also represent almost half of all Australians women’s contribution in the Australian Music Industry to be sidelined with a music qualification, and yet hold only one in four senior roles in our key music industry organisations. -

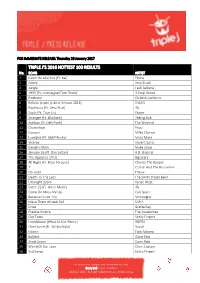

Triple J's 2016 Hottest 100 Results

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Thursday 26 January 2017 TRIPLE J’S 2016 HOTTEST 100 RESULTS No. SONG ARTIST 1 Never Be Like You {Ft. Kai} Flume 2 Adore Amy Shark 3 Jungle Tash Sultana 4 1955 {Ft. Montaigne/Tom Thum} Hilltop Hoods 5 Redbone Childish Gambino 6 Believe {triple j Like A Version 2016} DMA'S 7 Papercuts {Ft. Vera Blue} Illy 8 Say It {Ft. Tove Lo} Flume 9 Stranger {Ft. Elliphant} Peking Duk 10 Starboy {Ft. Daft Punk} The Weeknd 11 Chameleon Pnau 12 Cocoon Milky Chance 13 Love$ick {Ft. A$AP Rocky} Mura Masa 14 Viceroy Violent Soho 15 Genghis Khan Miike Snow 16 January 26 {Ft. Dan Sultan} A.B. Original 17 The Opposite Of Us Big Scary 18 All Night {Ft. Knox Fortune} Chance The Rapper 19 7 Catfish And The Bottlemen 20 On Hold The xx 21 Death To The Lads The Smith Street Band 22 Ultralight Beam Kanye West 23 Catch 22 {Ft. Anne-Marie} Illy 24 Come On Mess Me Up Cub Sport 25 Because I Love You Montaigne 26 Make Them Wheels Roll SAFIA 27 Drive Gretta Ray 28 Frankie Sinatra The Avalanches 29 Our Town Sticky Fingers 30 Innerbloom {What So Not Remix} RÜFÜS 31 One Dance {Ft. Wizkid/Kyla} Drake 32 Notion Tash Sultana 33 Bullshit Dune Rats 34 Scott Green Dune Rats 35 World Of Our Love Client Liaison 36 Sad Songs Sticky Fingers For more info, images and interviews contact: Gerry Bull, triple j Publicist 02 8333 1641 | [email protected] | triplej.net.au 37 Smoke & Retribution {Ft. -

Vmdo Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2018-2019 VMDO ANNUAL REPORT 2018-2019 i We acknowledge the traditional Aboriginal owners of country throughout Victoria and pay our respects to them, their culture and their Elders past, present and future. Contents 3 CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER’S REPORT 4 GENERAL MANAGER’S REPORT 6 ABOUT THE VMDO 8 STRATEGIC PLAN 2018 – 2021 15 THE YEAR IN REVIEW 16 THE FUTURE 22 MARKET DEVELOPMENT 28 MUSIC BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT 34 MUSIC BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT – FIRST PEOPLES 38 SUPPORT ACTS FOR THE BIG NAMES 40 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 40 ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURE 41 MUSIC VICTORIA BOARD 45 VMDO STEERING COMMITTEE 47 VMDO STAFF VMDO ANNUAL REPORT 2018-2019 1 “I think what I was struck by is that, very much like Nashville, there is such a deep music community here and there’s so much support that is really lovely and wonderful. You don’t get that in a lot of places. I feel that kinship in Melbourne the way we have it in Nashville” – Cameo Carlson, mtheory 2 VMDO ANNUAL REPORT 2018-2019 CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER’S REPORT Patrick Donovan, Music Victoria Music Victoria was contracted by Creative Victoria in 2018 to manage the Victorian Music Development Office as a major two year project. It was part of the State Government’s unprecedented 2014 Music Works commitment, which at the time was the largest contemporary music funding commitment made by a state or federal government in Australia, and will fund the Music Market development at the Collingwood Arts Precinct which will house the VMDO in 2020. Music Victoria hired general manager Bonnie Dalton, set up the office, and recruited consultants to develop the strategic and business plans, which included the vision: The VMDO will grow the prosperity of Victorian music businesses. -

Type Artist Album Barcode Price 32.95 21.95 20.95 26.95 26.95

Type Artist Album Barcode Price 10" 13th Floor Elevators You`re Gonna Miss Me (pic disc) 803415820412 32.95 10" A Perfect Circle Doomed/Disillusioned 4050538363975 21.95 10" A.F.I. All Hallow's Eve (Orange Vinyl) 888072367173 20.95 10" African Head Charge 2016RSD - Super Mystic Brakes 5060263721505 26.95 10" Allah-Las Covers #1 (Ltd) 184923124217 26.95 10" Andrew Jackson Jihad Only God Can Judge Me (white vinyl) 612851017214 24.95 10" Animals 2016RSD - Animal Tracks 018771849919 21.95 10" Animals The Animals Are Back 018771893417 21.95 10" Animals The Animals Is Here (EP) 018771893516 21.95 10" Beach Boys Surfin' Safari 5099997931119 26.95 10" Belly 2018RSD - Feel 888608668293 21.95 10" Black Flag Jealous Again (EP) 018861090719 26.95 10" Black Flag Six Pack 018861092010 26.95 10" Black Lips This Sick Beat 616892522843 26.95 10" Black Moth Super Rainbow Drippers n/a 20.95 10" Blitzen Trapper 2018RSD - Kids Album! 616948913199 32.95 10" Blossoms 2017RSD - Unplugged At Festival No. 6 602557297607 31.95 (45rpm) 10" Bon Jovi Live 2 (pic disc) 602537994205 26.95 10" Bouncing Souls Complete Control Recording Sessions 603967144314 17.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Dropping Bombs On the Sun (UFO 5055869542852 26.95 Paycheck) 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Groove Is In the Heart 5055869507837 28.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Mini Album Thingy Wingy (2x10") 5055869507585 47.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre The Sun Ship 5055869507783 20.95 10" Bugg, Jake Messed Up Kids 602537784158 22.95 10" Burial Rodent 5055869558495 22.95 10" Burial Subtemple / Beachfires 5055300386793 21.95 10" Butthole Surfers Locust Abortion Technician 868798000332 22.95 10" Butthole Surfers Locust Abortion Technician (Red 868798000325 29.95 Vinyl/Indie-retail-only) 10" Cisneros, Al Ark Procession/Jericho 781484055815 22.95 10" Civil Wars Between The Bars EP 888837937276 19.95 10" Clark, Gary Jr. -

Womens Connect with Like-Minded People? Maybe Just a Microwave Or Fridge for Your Lunch? Angela Griffin the SRC Has You Covered

1 THE TEAM CONTENTS Managing Editor 4 / Colleges: helpful or harmful when addressing sexual assault on campus? by Anonymous Angela Griffin 8 / The Right to Choose by Angela Griffin Designer 10 / #Metoo and #Withyou: How the #Metoo Amy Ge movement affected Korea by Christina Kim 12 / The Virgin Mary Series by Kate Alderton Contributors 18 / Sister can you hear me now by Hayley Anonymous, Angela Griffin, Christina Kim, Barrington Kate Alderton, Hayley Barrington, Abby Butler, Inderpreet Singh, Chantel Karin, Ella Bannon, 20 / The off-key treatment of women in the Lizzie Butterworth, Mary Rosenthall, Ruby Leonard, Alessandra Buxton, Ruby Pandolfi, music industry by Abby Butler Jemima Waddell, Cee Jay, Georgia Griffiths, Lili Occiuto, Mary Rosenthall, Zoe Ford 22 / He’s just not that inclusive of you by Inderpreet Singh Cover 23 / Natural Hair Art by Chantel Karin Annabel Caley 24 / Realities of Self Care by Ella Cannon 26 / Fighting Activist Burnout by Lizzie Butterworth 28 / Nature of Consent by Mary Rosenthall 30 / What is a mother-daughter relationship? by Ruby Leonard 32 / Fuck me please, I’m bleeding. by Alessandra Buxton 34 / What has sustainability got to do with periods? by Ruby Pandolfi Uncaptioned images used in this publication are in the public domain, kindly provided by the 36 / The rights of your butt and the nuances of British Library in their online collection on Flickr. club culture by Jemima Waddell Tharunka acknowledges the traditional custodians of this land, the Gadigal and Bedigal people of the 38 / Good Night by Cee Jay Eora nation, on which our university now stands. -

Triple J's 2017 Hottest 100 Songs No. Song Artist 1 HUMBLE. Kendrick

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Saturday 27 January 2018 triple j's 2017 Hottest 100 songs No. Song Artist 1 HUMBLE. Kendrick Lamar 2 Let Me Down Easy Gang Of Youths 3 Chateau Angus & Julia Stone 4 Ubu Methyl Ethel 5 The Deepest Sighs, The Frankest Shadows Gang Of Youths 6 Green Light Lorde 7 Go Bang PNAU 8 Sally {Ft. Mataya} Thundamentals 9 Lay It On Me Vance Joy 10 What Can I Do If The Fire Goes Out? Gang Of Youths 11 SWEET BROCKHAMPTON 12 Fake Magic Peking Duk & AlunaGeorge 13 Young Dumb & Broke Khalid 14 Homemade Dynamite Lorde 15 Regular Touch Vera Blue 16 Feel The Way I Do The Jungle Giants 17 Marryuna {Ft. Yirrmal} Baker Boy 18 Exactly How You Are Ball Park Music 19 The Man The Killers 20 Let You Down {Ft. Icona Pop} Peking Duk 21 Birthdays The Smith Street Band 22 Lemon To A Knife Fight The Wombats 23 Not Worth Hiding Alex The Astronaut 24 rockstar {Ft. 21 Savage} Post Malone 25 Weekends Amy Shark 26 Feel It Still Portugal. The Man 27 Be About You Winston Surfshirt 28 Mystik Tash Sultana 29 Mended Vera Blue 30 Low Blows Meg Mac 31 Lay Down Touch Sensitive 32 NUMB {Ft. GRAACE} Hayden James 33 Slow Mover Angie McMahon For more info, images and interviews contact: Gerry Bull, triple j Publicist 02 8333 1641 | [email protected] | triplej.net.au 34 DNA. Kendrick Lamar 35 Passionfruit Drake 36 I Haven't Been Taking Care Of Myself Alex Lahey 37 Slide {Ft. Frank Ocean/Migos} Calvin Harris 38 bellyache Billie Eilish 39 Got On My Skateboard Skegss 40 True Lovers Holy Holy 41 Blood {triple j Like A Version 2017} Gang Of Youths 42 Cola CamelPhat & Elderbrook 43 Murder To The Mind Tash Sultana 44 In Motion {Ft. -

Experiences and Perceptions of Gender in the Australian Music Industry

[PB 20.1 (2019) 8-39] Perfect Beat (print) ISSN 1038-2909 https://doi.org/10.1558/prbt.39800 Perfect Beat (online) ISSN 1836-0343 Hannah Fairlamb Bianca Fileborn Experiences and perceptions of gender in the Australian music industry Hannah Fairlamb is an Adelaide musician and University of Adelaide researcher, currently working on Kaurna coun- North Terrace try in State Government gender policy. She Adelaide SA 5000 is co-founder and co-director of youth music Australia mentoring project Girls Rock! Adelaide, and is [email protected] working towards solidifying this not-for-profit organization in the music industry landscape in South Australia. Dr Bianca Fileborn is a Lecturer in Criminology Room W606, John Medley Building and DECRA ARC Fellow in the School of Social and School of Social and Political Sciences Political Sciences, University of Melbourne. Her Faculty of Arts current work focuses on public harassment and University of Melbourne victim-centred justice, sexual violence and safety Parkville VIC 3010 at music festivals, and safety and harassment of Australia users of taxi and ride share services. [email protected] Abstract This article reports results from an online survey (n=207) about experiences and perceptions of gender from those working in the Australian music industry. Taking a feminist approach, theory on gender and hegemonic masculinity is used to discuss power in a gendered context in this industry. Literature shows women and girls experience a range of difficulties in the music industry worldwide, such as negative assumptions about their skill levels. The small body of research on gender and the Australian music industry has discussed topics such as the forget- ting of women in Australian popular music history. -

Battle for Syria: What Has a Usyd Academic Got to Do with Bashar Al-Assad? / P

Battle for Syria: What has a USyd academic got to do with Bashar al-Assad? / p. 19 Double page full colour Life on Manus Island: Four Sydney Writers’ Festival: pull-out poster: Risako birthdays in detention and a Rupi Kaur, John Safran and Katsumata’s artwork / p. 16 movie filmed in secret / p. 10 Melina Marchetta / p. 13 S1W13 / FIRST PUBLISHED 1929 S1W13 / FIRST HONI SOIT LETTERS SciSoc’s Final BBQ SUDS Presents: The Normal Heart Acknowledgement of Country When: Wednesday, June 7, 12:00pm- When: Wednesday, June 7 - Saturday, What’s on Women2:00pm in Science: Talks #4 WomenJune 10, in7:30pm Science: (7:00pm Talks Saturday)#4 We acknowledge the traditional custodians of this land, the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation. The University of Sydney – where we write, publish and distribute When:Where: Wednesday School of Chemistry, April 26, 4-5pm USyd- When:Where: Wednesday The Actor’s AprilPulse, 26, Redfern 4-5pm Honi Soit – is on the sovereign land of these people. As students and journalists, we recognise our complicity in the ongoing colonisation of Indigenous land. In Where:Price: FREE New with Law aAnnex 2017 SciSocRoom 428T-shirt / Where:Price: TBA New Law Annex Room 428 HowAccess much: $2 /Free Non-Access $6 How much: Free recognition of our privilege, we vow to not only include, but to prioritise and centre the experiences of Indigenous people, and to be reflective when we fail to. We Did you see that article? So awful recognise our duty to be a counterpoint to the racism that plagues the mainstream media, and to adequately represent the perspectives of Indigenous students at this week Honey, we should get lunch together I’m so happy Women in Science I’mhow sothe happy ceiling Womenfell down in inScience that lit - our University. -

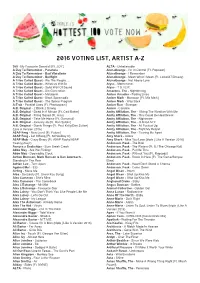

Artist A-Z, Triple J's 2016 Voting List

2016 VOTING LIST, ARTIST A-Z 360 - My Favourite Downfall {Ft. JOY.} ALTA - Unbelievable A Day To Remember - Paranoia AlunaGeorge - I'm In Control {Ft. Popcaan} A Day To Remember - Bad Vibrations AlunaGeorge - I Remember A Day To Remember - Bullfight AlunaGeorge - Mean What I Mean {Ft. Leikeli47/Dreezy} A Tribe Called Quest - We The People.... AlunaGeorge - Not Above Love A Tribe Called Quest - Whateva Will Be Alyss - Motherland A Tribe Called Quest - Solid Wall Of Sound Alyss - T S I E R A Tribe Called Quest - Dis Generation Amazons, The - Nightdriving A Tribe Called Quest - Melatonin Amber Arcades - Fading Lines A Tribe Called Quest - Black Spasmodic Amber Mark - Monsoon {Ft. Mia Mark} A Tribe Called Quest - The Space Program Amber Mark - Way Back A-Trak - Parallel Lines {Ft. Phantogram} Amber Run - Stranger A.B. Original - 2 Black 2 Strong Aminé - Caroline A.B. Original - Dead In A Minute {Ft. Caiti Baker} Amity Affliction, The - I Bring The Weather With Me A.B. Original - Firing Squad {Ft. Hau} Amity Affliction, The - This Could Be Heartbreak A.B. Original - Take Me Home {Ft. Gurrumul} Amity Affliction, The - Nightmare A.B. Original - January 26 {Ft. Dan Sultan} Amity Affliction, The - O.M.G.I.M.Y. A.B. Original - Dumb Things {Ft. Paul Kelly/Dan Sultan} Amity Affliction, The - All Fucked Up {Live A Version 2016} Amity Affliction, The - Fight My Regret A$AP Ferg - New Level {Ft. Future} Amity Affliction, The - Tearing Me Apart A$AP Ferg - Let It Bang {Ft. ScHoolboy Q} Amy Shark - Adore A$AP Mob - Crazy Brazy {Ft. -

ARIA TOP 100 VINYL ALBUM CHART 2018 TY TITLE Artist COMPANY CAT NO

CHART KEY TY THIS YEAR ARIA TOP 100 VINYL ALBUM CHART 2018 TY TITLE Artist COMPANY CAT NO. 1 GREATEST HITS Queen UNI/UMA 2758364 2 GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY: AWESOME MIX VOL. 1 Soundtrack HWR/UMA 8731446 3 NEVERMIND Nirvana UNI/UMA 2777908 4 TRANQUILITY BASE HOTEL & CASINO Arctic Monkeys DOM/EMI WIGCD339 5 BACK TO BLACK Amy Winehouse ISL/UMA 5304758 6 GO FARTHER IN LIGHTNESS Gang Of Youths SME 88985442992 7 GREATEST HITS II Queen UNI/UMA 2758365 8 ABBEY ROAD The Beatles EMI 3824682 9 THE BEATLES The Beatles CAP/EMI 3824662 10 PULP FICTION Original Soundtrack UMA 1130432 11 THE DARK SIDE OF THE MOON Pink Floyd PLG/WAR 0289552 12 CURRENTS Tame Impala MOD/UMA 4730676 13 RUMOURS Fleetwood Mac RHI/WAR 8122796778 14 ÷ Ed Sheeran ATL/WAR 9029585903 15 MTV - UNPLUGGED IN NEW YORK Nirvana GEF/UMA GEFD24727 16 DAMN. Kendrick Lamar INR/UMA 5760871 17 LEGEND: THE BEST OF BOB MARLEY AND THE WAILERS Bob Marley And The Wailers ISL/UMA 5489042 18 FLOW STATE Tash Sultana LLR/SME 19075870562 19 INTERNATIONALIST Powderfinger UMA 6758857 20 MTV UNPLUGGED (LIVE IN MELBOURNE) Gang Of Youths MOSY/SME 19075896422 21 REPUTATION Taylor Swift BIG/UMA 3003310 22 THRILLER Michael Jackson EPI/SME 5044222000 23 MY OWN MESS Skegss WAR RATBAG014CD 24 ODDMENTS King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard FLL/INE FLT-009RCD 25 EYES LIKE THE SKY King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard FLL/INE FLT-005RCD 26 FLOAT ALONG - FILL YOUR LUNGS King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard FLL/INE FLT-006RCD 27 MELODRAMA Lorde UNI/UMA 5754709 28 BECAUSE THE INTERNET Childish Gambino LIB/UMA LIB161CD 29 TRENCH Twenty