4.1 Lope De Vega's La Dama Boba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Undergraduate Research Forum · · · Tuesday, April 1, 2014 1:00-4:00 Pm, Mulva Library

UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH FORUM · · · TUESDAY, APRIL 1, 2014 1:00-4:00 PM, MULVA LIBRARY RECEPTION FOLLOWING · · · HENDRICKSON DINING ROOM 4:00-5:30 PM SPONSORED BY THE COLLABORATIVE: CENTER FOR UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH The Undergraduate Research Forum highlights the valued tradition at St. Norbert College of collaboration taking place in laboratories, studios, and other scholarly or creative settings between our students and our faculty and staff, resulting in a rich array of scholarly research and creative work. This celebration features collaborative projects that evolved out of independent studies, class assignments, and casual interactions as well as formal collaborations supported by internal grant funding. 1 Table of Contents Abstracts………………………………..……………………3-18 Biography of Dr. George Yancy………………………….......19 Acknowledgments……………………………………………..20 Schedule…………………………………………………....21-22 2 Abstracts are listed in alphabetical order by presenter’s last name. The Afferent Connectivity of the Substance P Reactive Nucleus (SPf) in the Zebra Finch is Sexually Monomorphic Hannah Andrekus, Senior Biology Major Kevin Beine, Senior Biology Major David Bailey, Associate Professor of Biology The lateral boundary of the hippocampus in birds, a band of cells named SPf (due to high levels of the neuropeptide substance P), may be a homolog of the mammalian entorhinal cortex, the primary hippocampal input. Little is known about the regions that communicate with SPf. Prior studies in our lab revealed that, in male zebra finches, SPf receives input from cells within a number of visual, auditory, and spatial memory- forming regions. We have extended this work to female birds using the retrograde tracer DiI and fluorescence microscopy, which have revealed the connections of this region to be sexually monomorphic. -

Abstracts I Ehumanista 24 (2013) Marta Albalá Pelegrín, El Arte Nuevo De Lope De Vega a La Luz De La Teoría Dramática Italia

Abstracts i Marta Albalá Pelegrín, El Arte nuevo de Lope de Vega a la luz de la teoría dramática italiana contemporánea: Poliziano, Robortello, Guarini y el Abad de Rute Abstract: Since the end of the 15th century Italian poetic theory was the stage of numerous polemics concerning the conception of comedy that deeply influenced Western theatrical production. During the 16th century we encounter two main currents of thought: one of them was constituted by theorist who, starting with Francesco Robortello (1516-1567), reread Aristotle's Poetics as a set of rules, with which to determine and judge the quality of contemporary artistic production; the other was composed by men of letters such as Angelo Poliziano (1454-1494) or Battista Guarini (1538-1612), who conceived of comedy as a historically changeable category, one which was generically malleable, and open to the innovations of contemporary playwrights. This article reveals Lope de Vega's New Art of Making Comedies (1609) as a text belonging to this latter tradition, with which it presents numerous concomitances and points of contact at both the discursive and the conceptual level. The existence of such actual relation is attested in a contemporary work that has been overlooked up to date, the Didascalia Multiplex (1615) by the Abbot of Rute (1565-1526). Resumen: Desde finales del siglo XV la teoría poética italiana fue escenario de numerosas polémicas en torno a la concepción de la comedia que tuvieron gran impacto en la producción teatral occidental. A lo largo del siglo XVI encontramos -

Internacional… . De Hispanistas… …

ASOCIACIÓN………. INTERNACIONAL… . DE HISPANISTAS… …. ASOCIACIÓN INTERNACIONAL DE HISPANISTAS 16/09 bibliografía publicado en colaboración con FUNDACIÓN DUQUES DE SORIA © Asociación Internacional de Hispanistas © Fundación Duques de Soria ISBN: 978-88-548-3311-1 Editora: Blanca L. de Mariscal Supervisión técnica: Claudia Lozano Maquetación: Debora Vaccari Índice EL HISPANISMO EN EL MUNDO: BIBLIOGRAFÍA Y CRÓNICA ÁFRICA Argelia, Marruecos y Túnez...................................................................................... 11 Egipto........................................................................................................................ 13 AMÉRICA Argentina.................................................................................................................... 14 Canadá........................................................................................................................ 22 Chile........................................................................................................................... 25 Estados Unidos........................................................................................................... 29 México........................................................................................................................ 41 Perú.............................................................................................................................49 Venezuela.................................................................................................................. -

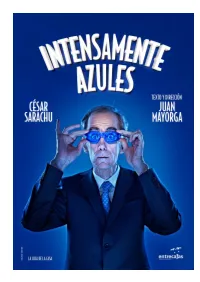

César Sarachu Actor

Mi hija pequeña me ha pedido que no vaya a ver sus partidos de baloncesto con gafas de nadar. Al explicarle que con ellas por fin entiendo las reglas e interpreto correctamente las jugadas, me ha respondido que puedo seguir yendo a sus partidos con gafas de nadar siempre que no me siente junto a los otros padres… Una mañana, al despertar, encontré en el suelo, rotas, mis gafas de miope. Tras algunos instantes de desconcierto, recuperé la calma al recordar que tenía otras gafas graduadas: las de natación, que mi familia me había regalado en un cumpleaños. El caso es que empecé a moverme con ellas por la casa, lo que sorprendió un poco a mis hijos –a mi mujer no; a ella no le sorprendió nada-, sobre todo cuando salí al supermercado a comprar leche, que hacía falta. Fue en el súper donde me di cuenta de que, tanto como el modo en que yo veía a la gente, cambiaba el modo en que la gente me veía a mí. Pruebe a ponerse unas gafas graduadas de natación y salga al mundo. Nadie se conformará con la explicación más sencilla –“Esta persona lleva esas gafas para no romperse la crisma”-. Unos te toman por provocador. Otros te tratan como alguien que necesita ayuda –ésos son los más peligrosos-. Algunos te prestan una atención que jamás te dieron. Y hay quien no te ve, quien te descarta como un error de su percepción –ante ésos vives en un estado de presencia ausencia muy interesante; ser una persona con gafas intensamente azules es lo más cerca que yo he estado de ser un ángel- Al salir del súper, en la calle, saqué la libreta DIN-A7 que siempre me acompaña y empecé a escribir sobre lo que me pasaba y sobre lo que podía pasarme –desde niño me ha costado diferenciar lo uno de lo otro; detrás de mis gafas azules, me resultaba imposible distinguir-. -

Preludio a La Dama Boba De Lope De Vega (Historia Y Crítica)

PRELUDIO A LA DAMA BOBA DE LOPE DE VEGA (HISTORIA Y CRÍTICA) Javier Espejo Surós y Carlos Mata Induráin (eds.) BIADIG | BIBLIOTECA ÁUREA DIGITAL DEL GRISO | 54 LA VERSIÓN DE LA DAMA BOBA DE FEDERICO GARCÍA LORCA Juan Aguilera Sastre Isabel Lizarraga Vizcarra Después del triunfal estreno de Bodas de sangre el 29 de julio de 1933 en el bonaerense Teatro Maipo, Lola Membrives lograba con- vencer a Federico García Lorca para que, acompañado por Manuel Fontanals, viajase a la capital porteña. Desde su llegada el 13 de octu- bre, a lo largo de casi medio año iba a consolidar de manera rotunda su prestigio como poeta, conferenciante y, sobre todo, como autor dramático tras las reposiciones en el Teatro Avenida de Bodas de san- gre, La zapatera prodigiosa y Mariana Pineda. Pero ni siquiera podía sospechar que aquel viaje iba a depararle un triunfo más: el de su versión escénica de La dama boba, de Lope de Vega, que realizó por encargo expreso de la actriz Eva Franco y se estrenó el 3 de marzo de 1934 en el Teatro de la Comedia. Llegó a alcanzar 161 representa- ciones consecutivas hasta el 17 de mayo (cerca de 200 en total), muy por encima de las 150 de Bodas de sangre en sucesivas reposiciones, las 70 de La zapatera prodigiosa o las 20 de Mariana Pineda. Este éxito espectacular continuaría posteriormente en España, con motivo del tricentenario de la muerte de Lope. Se estrenó al aire libre el 27 de agosto de 1935 en la Chopera del Retiro, a cargo de la compañía de Margarita Xirgu, dirigida por Cipriano de Rivas Cherif, y de allí pasó al escenario del Teatro Español y más tarde a los de Barcelona, Va- lencia, Bilbao, Logroño y Santander, así como a La Habana y Méxi- co, las primeras etapas de la gira americana de la compañía en 1936. -

What Is Authorial Philology? I a Paola Italia, Giulia Raboni, Et Al

I TAL What is Authorial Philology? I A PAOLA ITALIA, GIULIA RABONI, ET AL. R , ABON A stark departure from traditional philology, What is Authorial Philology? is the first comprehensive treatment of authorial philology as a discipline in its I , , own right. It provides readers with an excellent introduction to the theory ET and practice of editing ‘authorial texts’ alongside an exploration of authorial AL philology in its cultural and conceptual architecture. The originality and . distinction of this work lies in its clear systematization of a discipline whose W autonomous status has only recently been recognised. What is Authorial This pioneering volume offers both a methodical set of instructions on how to read critical editions, and a wide range of practical examples, expanding Philology? upon the conceptual and methodological apparatus laid out in the first two chapters. By presenting a thorough account of the historical and theoretical framework through which authorial philology developed, Paola Italia, Giulia HAT Raboni and their co-authors successfully reconceptualize the authorial text as I S an ever-changing organism, subject to alteration and modification. A UTHO What is Authorial Philology? will be of great didactic value to students and researchers alike, providing readers with a fuller understanding of the rationale behind different editing practices, and addressing both traditional and newer RI AL methods such as the use of the digital medium and its implications. Spanning P PAOLA ITALIA, GIULIA RABONI, ET AL. the whole Italian tradition from Petrarch to Carlo Emilio Gadda, and with H I examples from key works of European literature, this ground-breaking volume LOLO provokes us to consider important questions concerning a text’s dynamism, the extent to which an author is ‘agentive’, and, most crucially, about the very G Y nature of what we read. -

Performing Recognition: El Castigo Sin Venganza and the Politics of the ‘Literal’ Translation

Performing Recognition: El castigo sin venganza and the Politics of the ‘Literal’ Translation Sarah Maitland Cielos, / hoy se ha de ver en mi casa / no más de vuestro castigo. – El castigo sin venganza In the opening scene of El castigo sin venganza the Duke of Ferrara is in disguise. So soon before his wedding to Casandra, and despite the rumours of his debauchery, it is imperative that his hunt for female entertainment goes unnoticed. His position requires him to take a wife; in so doing, he ensures justice for the people by avoiding civil war. Yet by denying his freedom-loving nature, he must do injustice to himself. When he learns of Casandra’s affair with his son Federico, rather than make their adultery public he contrives her death at Federico’s own hand. What the people see, however, is the righteous execution of the man who murdered Casandra out of jealousy for his lost inheritance. Through lies and subterfuge the Duke ensures that in public his honour is protected while in private he enacts their punishment. This is a play that deals in disguise. It locates itself in the slippery distinctions between duty and desire, private sentiment and public action, moral justice and its public fulfilment. Unlike today, where transparent democracy demands that every stage of the criminal justice process is available to public scrutiny, in Ferrara, where honour is directly proportional to public standing, due process is a function of public perception. This situation places the Duke in an invidious position. He has been harmed on two fronts – by his wife’s adultery and his son’s treachery – but to seek justice would be to make their betrayal public, damaging his reputation and thereby creating a third, even greater harm: the loss of support for the legitimacy of his rule. -

ABSTRACTS More Hostile Toward the Idea

Newberry Center for Renaissance Studies modernity. Similar to but not synonymous with indigeneity and aboriginality, autochthony has a range of meanings, including that 2016 Multidisciplinary life literally springs from the earth itself, and that territorial sovereignty belongs to native-born inhabitants rather than Graduate Student Conference immigrants. In contrast to ancient Athenians, who were proud to claim autochthony, English authors from Edmund Spenser to Thomas Browne were more ambivalent about and ultimately ABSTRACTS more hostile toward the idea. In the Faerie Queene (1596), Spenser grounds an historical fiction of English origins on the triumph of settlers over autochthones. Browne, for his part, deems autochthony “repugnant” to chronology, theology, and THURSDAY AFTERNOON SESSIONS philosophy. Whereas ancient and present-day expressions of autochthony function primarily as political myth-ideologies, early modern autochthony was additionally inextricable from 1: COSMOGRAPHY, SPACE, PLACE theological and scientific questions, including genesis and Chair: Monica Solomon Philosophy, Notre Dame spontaneous generation. This paper works to give new perspective on the ways seventeenth-century authors conceived The Medieval Heliocentrism of Mercury and Venus: A New and related to the “earth itself” during a time of geo-fugal Interpretation of William of Conches’ Argument for tendencies, including shifts from predominantly terrestrial to Planetary Order maritime existence, and the gradual turn from Ptolemaic James Brannon History of Science, Wisconsin-Madison geocentrism toward Copernican heliocentrism. I show that despite their adamant disavowal of autochthony, both Spenser The twelfth-century scholar William of Conches adhered to the and Browne explore and experiment with the concept’s peculiar established planetary order of the moon closest to earth, with consequences for historiography. -

Comedia Performance

Comedia Performance Journal of The Association for Hispanic Classical Theater Volume 12, Number 1, Spring 2015 www.comediaperformance.org Comedia Performance Journal of the Association For Hispanic Classical Theater Barbara Mujica, Editor Box 571039 Georgetown University Washington, D. C. 20057 We dedicate this issue to the memory of our colleagues Vern G. Williamsen Francisco Ruiz Ramón Shirley Whitaker Volume 12, Number 1 Spring 2015 ISSN 1553-6505 Comedia Performance This issue was guest-edited by David Johnston (Queen’s University Belfast), Donald R. Larson (The Ohio State University), Susan Paun de García (Denison University), and Jonathan Thacker (Merton College, University of Oxford). Editorial Board Barbara Mujica – Editor Department of Spanish and Portuguese, Box 571039 Georgetown University Washington, D. C. 20057-1039 [email protected] [email protected] Gwyn Campbell – Managing Editor Department of Romance Languages Washington and Lee University Lexington, VA 24450 [email protected] Sharon Voros – Book Review Editor Department of Modern Languages US Naval Academy Annapolis, MD 21402-5030 [email protected] Darci Strother – Theater Review Editor Department of World Languages & Hispanic Literatures California State University San Marcos San Marcos, CA 92096-0001 [email protected] Michael McGrath – Interviews Editor Department of Foreign Languages P.O. Box 8081 Georgia Southern University Statesboro, GA 30460 [email protected] Editorial Staff Ross Karlan – Editorial Assistant [email protected] -

La Dama Boba

La dama boba 1 La dama boba Lope de Vega La dama boba 1 Personas que hablan en ella: LISEO, caballero galán TURÍN, lacayo LEANDRO, estudiante OCTAVIO, viejo MISENO, su amigo DUARDO, caballero FENISO, caballero LAURENCIO, caballero galán RUFINO, maestro NISE, dama FINEA, su hermana CELIA, criada CLARA, criada PEDRO, lacayo MÚSICOS La dama boba 2 Acto primero Salen LISEO, caballero, y TURÍN, lacayo, los dos de camino LISEO: ¡Qué lindas posadas! TURÍN: ¡Frescas! LISEO: ¿No hay calor? TURÍN: Chinches y ropa tienen fama en toda Europa. LISEO: ¡Famoso lugar en Illescas! No hay en todos los que miras quien le iguale. TURÍN: Aun si supieses la causa... LISEO: ¿Cuál es? TURÍN: Dos meses de guindas y de mentiras. LISEO: Como aquí, Turín, se juntan de la corte y de Sevilla, Andalucía y Castilla, La dama boba 3 unos a otros preguntan: unos de las Indias cuentan, y otros, con discursos largos de provisiones y cargos, cosas que al vulgo alimentan. ¿No tomaste las medidas? TURÍN: Una docena tomé. LISEO: ¿E imágenes? TURÍN: Con la fe que son de España admitidas por milagrosas en todo cuanto en cualquiera ocasión les pide la devoción y el nombre. LISEO: Pues, de ese modo, lleguen las postas, y vamos. TURÍN: ¿No has de comer? LISEO: Aguardar a que se guise es pensar que a media noche llegamos; y un desposado, Turín, ha de llegar cuando pueda lucir. TURÍN: Muy atrás se queda con el repuesto Marín; La dama boba 4 pero yo traigo que comas. LISEO: ¿Qué traes? TURÍN: Ya lo verás. LISEO: Dilo. -

María Guerrero En El Museo Nacional Del Prado” Julia Amezúa

“María Guerrero en el Museo Nacional del Prado” Julia Amezúa MARÍA GUERRERO EN EL MUSEO NACIONAL DEL PRADO JULIA AMEZÚA (Escuela de Arte y Superior CRBC. Palencia). IV Encuentro entre el Profesorado. 23 de abril de 2016. 1 “María Guerrero en el Museo Nacional del Prado” Julia Amezúa ÍNDICE 1.- Introducción................................................................................................4 1.1. Características de la unidad didáctica...........................................4 1.2. Objetivos........................................................................................5 1.3. Contenidos.....................................................................................6 1.4. Metodología....................................................................................7 1.5. Recursos y materiales didácticos...................................................9 1.6. Criterios de evaluación. .................................................................9 2.- Primera parte. ¿Quién es María Guerrero?................................................10 2.1.- Presentación de la actriz. .............................................................10 2.2.- Realización del test María Guerrero..............................................11 2.3.- Guía didáctica para el profesor. Comentario del test.....................13 3.- Segunda parte. “Doña Inés del alma mía”...................................................18 3.1.- Puesta en común sobre el retrato..................................................19 3.2.- Conoce al pintor -

Locos Y Bobos : Dos Máscaras Fingidas En Elteatro De Lope De Vega (Con Un Excurso Calderoniano) Adrián J

Publié dans eHumanista 24, 271-292, 2013, 1 source qui doit être utilisée pour toute référence à ce travail Locos y bobos : dos máscaras fingidas en elteatro de Lope de Vega (con un excurso calderoniano) Adrián J. Sáez CEA-Université de Neuchâtel “Ihr könntet gar keine bessere Maske tragen […] als euer eignes Gesicht” (Nietzsche, Also sprach Zarathustra). En la comedia áurea, y especialmente en los géneros cómicos, proliferan los personajes ingeniosos y tracistas que para lograr sus fines simulan ser lo que no son, adoptan una identidad fingida. Pueden valerse para ello de máscaras, mutaciones de vestuario (Juárez Almendros), registro y nombre (signos externos), como los hábitos transexuales —dama vestida de hombre y el inverso, menos frecuente (Fernández Mosquera)— o los disfraces de jardineros (Trambaioli, “Variaciones”; “El jardinero fingido”), maestros, etc., sin olvidar el embozo que oculta la identidad y permite una mayor libertad, al margen de la mirada de la sociedad; o bien se puede ofrecer una nueva cara al mundo mediante un cambio de actitud o estado mental (signos más internos): baste recordar la devoción simulada por la protagonista de la tirsiana Marta la piadosa (Fernández Rodríguez, 2006) los nobles que se hacen pasar por villanos y viceversa (Eiroa)1. De ambos mecanismos se generan lances metateatrales, “una técnica por la que los personajes asumen conscientemente identidades diferentes a las suyas” e interpretan un papel de cara al resto de figuras (García Reidy 184). Este segundo paradigma —signos de procedencia interna— puede definirse como una máscara en sentido metafórico, dentro de la tensión entre ser y parecer, el arte del fingimiento articulado en la gran metáfora del theatrum mundi2.