History of the Government Sponsored Enterprises.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SC13-2384 Exhibit D (Lavalle)

EXHIBIT D REPORT ON NYE LAVALLE’S INVESTIGATIONS, RESEARCH BACKGROUND, BONA FIDES, EXPERTISE, & EXPERIENCE IN PREDATORY MORTGAGE SECURITIZATION, SERVICING, FORECLOSURE & ROBO-SIGNING PRACTICES INTRODUCTION 1. My name is Aneurin Adlai Lavalle. I am most commonly referred to as Nye Lavalle. I am a resident of the State of Florida. 2. I provide this report based upon facts and information personally known by me and to me and gathered from my research and investigation over a period of more than twenty-years. 3. I have a research background and as a consumer and shareholder advocate, I have developed a series of skills, procedures, and protocols over 20-years that has led me to be an expert in predatory mortgage securitization, servicing, and foreclosure fraud issues with a specialty in robo-signing.1 4. I have been accepted by Courts as an expert in matters relating to predatory mortgage securitization, servicing, and foreclosure fraud issues. 5. My findings, analyses, opinions, and many of my protocols, opinions, and conclusions have been reviewed, corroborated, and adopted by state and Federal regulatory agencies such as the Federal Reserve, Office of Comptroller of the Currency; Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Federal Housing Financing Agency, U.S. Attorney General and Attorneys General from all 50 states, FILED, 02/04/2015 12:11 am, JOHN A. TOMASINO, CLERK, SUPREME COURT including Florida, but especially by those in New York, Delaware, Nevada, and California. 1 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nye_Lavalle 1 6. In addition, numerous state and federal courts, including the Supreme and highest courts of the states of Massachusetts,2 Maryland,3 and Kansas4 have agreed with some of my opinions, findings, conclusions, and analyses I have developed over the last twenty-years. -

Ginnie Mae: How Does It Work and What Does It Do?

Economic Policy Program Housing Commission Ginnie Mae: How Does it Work and What Does it Do? The Government National Mortgage What Does Ginnie Mae Do? Association (or Ginnie Mae) is a Ginnie Mae only guarantees securities created by approved government corporation within the issuers and backed by mortgages covered by other federal U.S. Department of Housing and programs. Urban Development (HUD). It was The Ginnie Mae guarantee ensures that investors in these established in 1968 when Fannie mortgage-backed securities (MBS) do not experience any Mae was privatized. Its mission is disruption of the timely payment of principal and interest, thus shielding them from losses resulting from borrower to expand funding for mortgages defaults. As a result, these MBS appeal to a wide range that are insured or guaranteed by of investors and trade at a price similar to that of U.S. other federal agencies. When these government bonds of comparable maturity. However, the guarantee also places Ginnie Mae, and ultimately American mortgages are bundled into securities, taxpayers, at risk of losses not covered by the other federal Ginnie Mae provides a full-faith-and- programs (see When Does a Ginnie Mae Guarantee Apply?). credit guarantee on these securities, thus lessening the risk for investors and broadening the market for the securities. WWW.BIPARTISANPOLICY.ORG When Does a Ginnie Mae Why Does Ginnie Mae Use the Term Guarantee Apply? “Issuer/Servicer?” Ginnie Mae guarantees MBS backed by loans covered Ginnie Mae MBS can include mortgages by the following programs: purchased from multiple originators n The Federal Housing Administration’s single-family and multifamily mortgage insurance programs, which and serviced by third parties. -

Housing and the Financial Crisis

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Housing and the Financial Crisis Volume Author/Editor: Edward L. Glaeser and Todd Sinai, editors Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 978-0-226-03058-6 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/glae11-1 Conference Date: November 17-18, 2011 Publication Date: August 2013 Chapter Title: The Future of the Government-Sponsored Enterprises: The Role for Government in the U.S. Mortgage Market Chapter Author(s): Dwight Jaffee, John M. Quigley Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c12625 Chapter pages in book: (p. 361 - 417) 8 The Future of the Government- Sponsored Enterprises The Role for Government in the US Mortgage Market Dwight Jaffee and John M. Quigley 8.1 Introduction The two large government- sponsored housing enterprises (GSEs),1 the Federal National Mortgage Association (“Fannie Mae”) and the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (“Freddie Mac”), evolved over three- quarters of a century from a single small government agency, to a large and powerful duopoly, and ultimately to insolvent institutions protected from bankruptcy only by the full faith and credit of the US government. From the beginning of 2008 to the end of 2011, the two GSEs lost capital of $266 billion, requiring draws of $188 billion under the Treasured Preferred Stock Purchase Agreements to remain in operation; see Federal Housing Finance Agency (2011). This downfall of the two GSEs was primarily a question of “when,” not “if,” given that their structure as a public/private Dwight Jaffee is the Willis Booth Professor of Banking, Finance, and Real Estate at the University of California, Berkeley. -

Primers Federal Home Loan Banks Feb. 8, 2021

The NAIC’s Capital Markets Bureau monitors developments in the capital markets globally and analyzes their potential impact on the investment portfolios of U.S. insurance companies. Please see the Capital Markets Bureau website at INDEX. Federal Home Loan Banks Analyst: Jennifer Johnson Executive Summary • The Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB) system was established in 1932 for the purpose of providing liquidity and transparency to the capital markets. • It is comprised of 11 regional banks that are government-sponsored entities (GSEs) and support the market for homes. These FHLB regional banks provide low-cost financing to member financial institutions, which in turn make loans to individuals. • Each FHLB regional bank is structured as a cooperative of mortgage lenders, or members, which sets its credit standards and lending policies. To become a member, a financial institution must purchase shares of the regional bank. • FHLB regional bank members may apply for a loan or “advance” based on required credit limits and borrowing capacity. Each loan or advance is secured by eligible collateral, and lending capacity is based on applicable discount rates on the eligible collateral. The more liquid and easily valued the collateral, the lower the discount rate. • Eligible collateral may include U.S. government or government agency securities; residential mortgage loans; residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS); multifamily mortgage loans; cash; deposits in an FHLB regional bank; and other real estate-related assets such as commercial What is thereal FHLB estate? loans. • U.S. insurers interact with the FHLB system via borrowing, investing in FHLB debt and owning stock in FHLB regional banks. -

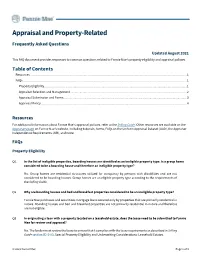

Appraisal and Property Related Faqs

Appraisal and Property-Related Frequently Asked Questions Updated August 2021 This FAQ document provides responses to common questions related to Fannie Mae’s property eligibility and appraisal policies. Table of Contents Resources .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 FAQs ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Property Eligibility ............................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Appraiser Selection and Management ............................................................................................................................................. 2 Appraisal Submission and Forms ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 Appraisal Policy ................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Resources For additional information about Fannie Mae’s appraisal policies, refer to the Selling Guide. Other resources are available on the Appraisers page on Fannie Mae’s -

Fred Solomon 703-903-3861 Frederick [email protected]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 14, 2019 MEDIA CONTACT: Fred Solomon 703-903-3861 [email protected] Freddie Mac Sells $307 Million in NPLs Awards 3 SPO Pools to 2 Winners McLean, Va. - Freddie Mac (OTCQB: FMCC) today announced it sold via auction 1,789 non-performing residential first lien loans (NPLs) from its mortgage-related investments portfolio. The loans, totaling approximately $307 million, are currently serviced by NewRez LLC, doing business as Shellpoint Mortgage Servicing. The transaction is expected to settle in July 2019. The sale is part of Freddie Mac’s Standard Pool Offerings (SPO®). Bids for the upcoming Extended Timeline Pool Offering (EXPO), which is a smaller sized pool of loans, are due from qualified bidders by May 21, 2019. Freddie Mac, through its advisors, began marketing the transaction on April 11, 2019 to potential bidders, including non-profits and Minority, Women, Disabled, LGBT, Veteran or Service-Disabled Veteran-Owned Businesses (MWDOBs), neighborhood advocacy organizations and private investors active in the NPL market. For the SPO® offerings, the loans were offered as three separate pools of mortgage loans. The three pools consist of mortgage loans secured by geographically diverse properties. Investors had the flexibility to bid on each pool individually and/or any combination of pools. Given the delinquency status of the loans, the borrowers have likely been evaluated previously for or are already in various stages of loss mitigation, including modification or other alternatives to foreclosure, or are in foreclosure. Mortgages that were previously modified and subsequently became delinquent comprise approximately 57 percent of the aggregate pool balance. -

THE 2019 STRATEGIC PLAN for the CONSERVATORSHIPS of FANNIE MAE and FREDDIE MAC October 2019

THE 2019 STRATEGIC PLAN FOR THE CONSERVATORSHIPS OF FANNIE MAE AND FREDDIE MAC October 2019 Page Footer Division of Conservatorship THE 2019 STRATEGIC PLAN FOR THE CONSERVATORSHIPS OF FANNIE MAE AND FREDDIE MAC Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................. 1 Introduction ........................................................................................... 6 A History of the Federal Housing Finance Agency and the Conservatorships of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac .................................. 6 A New Conservatorship Strategic Plan ........................................................ 9 I. Changes to the Market 9 II. Changes to the Regulator 10 III. Changes to the Enterprises 10 Executing the Strategic Plan: A New Scorecard With 3 Key Objectives ............ 11 I. Section 1: Foster a CLEAR National Housing Finance Markets 12 II. Section 2: Operate in a Safe and Sound Manner Appropriate for Conservatorship 13 III. Section 3: Prepare to Exit Conservatorship 15 Conclusion ............................................................................................ 16 i THE 2019 STRATEGIC PLAN FOR THE CONSERVATORSHIPS OF FANNIE MAE AND FREDDIE MAC Executive Summary September 6, 2019, marked 11 years since the Federal National Mortgage Association and the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, respectively, and together the Enterprises) were placed into conservatorships in the middle of the financial crisis of 2008. A root cause of the -

Uniform Collateral Data Portal® (UCDP®) User Guide for Fannie Mae Messaging

Uniform Collateral Data Portal® (UCDP®) User Guide for Fannie Mae Messaging September 2021 © 2021 Fannie Mae September 2021 Page 1 of 24 Table of Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 What is the UCDP User Guide for Fannie Mae Messaging? ............................................................................................................... 3 Who should read this manual? .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 What’s in this manual? .......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 1. View/Edit Pages for Appraisal Submissions .......................................................................................................................... 3 Figure 1.0.1 View/Edit Page with Fannie Mae Tabs .............................................................................................................................. 4 Table 1.0.2 Appraisal Information Subsections .................................................................................................................................... 5 2. Viewing and Editing Appraisal Information ......................................................................................................................... -

Your Step-By-Step Mortgage Guide

Your Step-by-Step Mortgage Guide From Application to Closing Table of Contents In this Guide, you will learn about one of the most important steps in the homebuying process — obtaining a mortgage. The materials in this Guide will take you from application to closing and they’ll even address the first months of homeownership to show you the kinds of things you need to do to keep your home. Knowing what to expect will give you the confidence you need to make the best decisions about your home purchase. 1. Overview of the Mortgage Process ...................................................................Page 1 2. Understanding the People and Their Services ...................................................Page 3 3. What You Should Know About Your Mortgage Loan Application .......................Page 5 4. Understanding Your Costs Through Estimates, Disclosures and More ...............Page 8 5. What You Should Know About Your Closing .....................................................Page 11 6. Owning and Keeping Your Home ......................................................................Page 13 7. Glossary of Mortgage Terms .............................................................................Page 15 Your Step-by-Step Mortgage Guide your financial readiness. Or you can contact a Freddie Mac 1. Overview of the Borrower Help Center or Network which are trusted non- profit intermediaries with HUD-certified counselors on staff Mortgage Process that offer prepurchase homebuyer education as well as financial literacy using tools such as the Freddie Mac CreditSmart® curriculum to help achieve successful and Taking the Right Steps sustainable homeownership. Visit http://myhome.fred- diemac.com/resources/borrowerhelpcenters.html for a to Buy Your New Home directory and more information on their services. Next, Buying a home is an exciting experience, but it can be talk to a loan officer to review your income and expenses, one of the most challenging if you don’t understand which can be used to determine the type and amount of the mortgage process. -

Financial Crises and Policy Responses

Financial Crises and Policy Responses A MARKET-BASED VIEW FROM THE SHADOW FINANCIAL REGULATORY COMMITTEE, 1986–2015 ROBERT LITAN NOVEMBER 2016 AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE Financial Crises and Policy Responses A MARKET-BASED VIEW FROM THE SHADOW FINANCIAL REGULATORY COMMITTEE, 1986–2015 ROBERT LITAN NOVEMBER 2016 AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE © 2016 by the American Enterprise Institute. All rights reserved. The American Enterprise Institute (AEI) is a nonpartisan, nonprofit, 501(c)(3) educational organization and does not take institutional posi- tions on any issues. The views expressed here are those of the author(s). Table of Contents Preface ................................................................................................................................................................................... v I. Financial Crises and Challenges: The Origins of the Shadow Financial Regulatory Committee ..... 1 II. A Brief 30-Year History of Finance ..................................................................................................................... 5 III. The S&L Crises of the 1980s ................................................................................................................................. 7 IV. The Banking Crises of the 1980s and Policy Responses .............................................................................. 11 V. Deposit Insurance and Safety-Net Reform .................................................................................................... 17 VI. Banking Regulation -

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in Conservatorship: Frequently Asked Questions

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in Conservatorship: Frequently Asked Questions Updated May 31, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44525 Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in Conservatorship: Frequently Asked Questions Summary Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are chartered by Congress as government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) to provide liquidity in the mortgage market and promote homeownership for underserved groups and locations. The GSEs purchase mortgages, retain the credit risk (for a fee), and package them into mortgage-backed securities (MBSs) that they either keep as investments or sell to institutional investors. In the years following the housing and mortgage market turmoil that began around 2007, the GSEs experienced financial difficulty. By 2008, the GSEs’ financial condition had weakened, generating concerns over their ability to meet their combined obligations on $1.2 trillion in bonds and $3.7 trillion in MBSs that they had guaranteed at the time. In response, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), the GSEs’ primary regulator, took control of them in a process known as conservatorship. Subject to the terms of the Senior Preferred Stock Purchase Agreements (PSPAs) between the U.S. Treasury and the GSEs, Treasury provided funds to keep the GSEs solvent. The GSEs initially agreed to pay Treasury a 10% cash dividend on funds received, and dividends were suspended for all other GSE stockholders. If the GSEs had enough profit at the end of the quarter, the dividend came out of the profit. When the GSEs did not have enough cash to pay their dividend to Treasury, they asked for additional cash to make the payment instead of issuing additional stock. -

Elizabeth a Duke: a Framework for Analyzing Bank Lending

Elizabeth A Duke: A framework for analyzing bank lending Speech by Ms Elizabeth A Duke, Member of the Board of Governors of the US Federal Reserve System, at the 13th Annual University of North Carolina Banking Institute, Charlotte, North Carolina, 30 March 2009. The original speech, which contains figures and various links to the documents mentioned, can be found on the US Federal Reserve System’s website. * * * In August 2008 I joined the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, leaving behind a 30-year career as a commercial banker to become a central banker. My time as a commercial banker spanned numerous business cycles. It also encompassed at least one severe financial system crisis, in the late 1980s through the early 1990s, albeit one that was not as severe as the current one. From my time as a commercial banker, I already understood the factors considered by bankers in the initial lending decision as well as those in loss mitigation when collecting those same loans. As a central banker, I have come to appreciate even more fully the role of credit in our economic well-being. So I thought it would be appropriate for me to provide my perspective on credit conditions in our economy and the current crisis. Today, I would like to discuss a three-dimensional view of the flow of credit to households and businesses and describe the evolving role of banks in the U.S. economy. I will begin by taking a look at recent trends in aggregate borrowing by households and by the nonfinancial business sector.