British and German Army Women

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interaction and Perception in Anglo-German Armies: 1689-1815

Interaction and Perception in Anglo-German Armies: 1689-1815 Mark Wishon Ph.D. Thesis, 2011 Department of History University College London Gower Street London 1 I, Mark Wishon confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 ABSTRACT Throughout the ‘long eighteenth century’ Britain was heavily reliant upon soldiers from states within the Holy Roman Empire to augment British forces during times of war, especially in the repeated conflicts with Bourbon, Revolutionary, and Napoleonic France. The disparity in populations between these two rival powers, and the British public’s reluctance to maintain a large standing army, made this external source of manpower of crucial importance. Whereas the majority of these forces were acting in the capacity of allies, ‘auxiliary’ forces were hired as well, and from the mid-century onwards, a small but steadily increasing number of German men would serve within British regiments or distinct formations referred to as ‘Foreign Corps’. Employing or allying with these troops would result in these Anglo- German armies operating not only on the European continent but in the American Colonies, Caribbean and within the British Isles as well. Within these multinational coalitions, soldiers would encounter and interact with one another in a variety of professional and informal venues, and many participants recorded their opinions of these foreign ‘brother-soldiers’ in journals, private correspondence, or memoirs. These commentaries are an invaluable source for understanding how individual Briton’s viewed some of their most valued and consistent allies – discussions that are just as insightful as comparisons made with their French enemies. -

The German Military and Hitler

RESOURCES ON THE GERMAN MILITARY AND THE HOLOCAUST The German Military and Hitler Adolf Hitler addresses a rally of the Nazi paramilitary formation, the SA (Sturmabteilung), in 1933. By 1934, the SA had grown to nearly four million members, significantly outnumbering the 100,000 man professional army. US Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of William O. McWorkman The military played an important role in Germany. It was closely identified with the essence of the nation and operated largely independent of civilian control or politics. With the 1919 Treaty of Versailles after World War I, the victorious powers attempted to undercut the basis for German militarism by imposing restrictions on the German armed forces, including limiting the army to 100,000 men, curtailing the navy, eliminating the air force, and abolishing the military training academies and the General Staff (the elite German military planning institution). On February 3, 1933, four days after being appointed chancellor, Adolf Hitler met with top military leaders to talk candidly about his plans to establish a dictatorship, rebuild the military, reclaim lost territories, and wage war. Although they shared many policy goals (including the cancellation of the Treaty of Versailles, the continued >> RESOURCES ON THE GERMAN MILITARY AND THE HOLOCAUST German Military Leadership and Hitler (continued) expansion of the German armed forces, and the destruction of the perceived communist threat both at home and abroad), many among the military leadership did not fully trust Hitler because of his radicalism and populism. In the following years, however, Hitler gradually established full authority over the military. For example, the 1934 purge of the Nazi Party paramilitary formation, the SA (Sturmabteilung), helped solidify the military’s position in the Third Reich and win the support of its leaders. -

WHO's WHO in the WAR in EUROPE the War in Europe 7 CHARLES DE GAULLE

who’s Who in the War in Europe (National Archives and Records Administration, 342-FH-3A-20068.) POLITICAL LEADERS Allies FRANKLIN DELANO ROOSEVELT When World War II began, many Americans strongly opposed involvement in foreign conflicts. President Roosevelt maintained official USneutrality but supported measures like the Lend-Lease Act, which provided invaluable aid to countries battling Axis aggression. After Pearl Harbor and Germany’s declaration of war on the United States, Roosevelt rallied the country to fight the Axis powers as part of the Grand Alliance with Great Britain and the Soviet Union. (Image: Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-128765.) WINSTON CHURCHILL In the 1930s, Churchill fiercely opposed Westernappeasement of Nazi Germany. He became prime minister in May 1940 following a German blitzkrieg (lightning war) against Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. He then played a pivotal role in building a global alliance to stop the German juggernaut. One of the greatest orators of the century, Churchill raised the spirits of his countrymen through the war’s darkest days as Germany threatened to invade Great Britain and unleashed a devastating nighttime bombing program on London and other major cities. (Image: Library of Congress, LC-USW33-019093-C.) JOSEPH STALIN Stalin rose through the ranks of the Communist Party to emerge as the absolute ruler of the Soviet Union. In the 1930s, he conducted a reign of terror against his political opponents, including much of the country’s top military leadership. His purge of Red Army generals suspected of being disloyal to him left his country desperately unprepared when Germany invaded in June 1941. -

Military Rearmament and Industrial Competition in Spain Jean-François Berdah

Military Rearmament and Industrial Competition in Spain Jean-François Berdah To cite this version: Jean-François Berdah. Military Rearmament and Industrial Competition in Spain: Germany versus Great Britain, 1921-1931. Tid og Tanke, Oslo: Unipub, 2005, pp.135-168. hal-00180498 HAL Id: hal-00180498 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00180498 Submitted on 19 Oct 2007 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Military Rearmament and Industrial Competition in Spain: Germany vs. Britain (1921-1931) Jean-François Berdah Toulouse II-Le Mirail University, France The loss of Cuba, the Philippines and Porto Rico as a consequence of the Spanish military defeat against the US Navy in 1898 was considered by the public opinion not only as a tragic humiliation, but also as a national disaster. In spite of the subsequent political and moral crisis, the Spanish government and the young King Alfonso XIII intended nevertheless to rebuild the Army according to their strong belief that Spain still remained a great power. But very soon the conscience of the poor technical level of the national industry forced the Spanish government to gain the support of the foreign knowledge and financial resources. -

European Security and Defence

Berlin BSC Security Conference 17th Congress on European Security and Defence European Security and Defence – remaining Transatlantic, acting more European 27 – 28 November 2018 About the Congress: » One of the largest yearly events on European Security and Defence Vienna House Andel’s Berlin » Meeting place for up to 1 000 participants from more than Landsberger Allee 106 50 countries D-10369 Berlin » International forum for members of parliament, politicians and representatives of the armed forces, security organisations and www.euro-defence.eu industry » Partner in 2018: The Netherlands » Former Partners: Russia, United Kingdom, Turkey, USA, France, Sweden » Exhibition with companies from Europe and abroad » Organised by the – Germany’s leading independent Newspaper for the Civil and Military Services Advisory Board Prof Ioan Mircea Pa s¸ cu Niels Annen Michel Barnier Wolfgang Hellmich MEP, Vice-President of the European Parliament, MP, Minister of State, Chief Negotiator, Head of MP, Chairman of former Defence Minister of Romania, Congress German Federal Foreign Task Force under Article the Defence Committee, President BSC 2018 Office 50 TEU with UK, former German Bundestag Advisor of President Juncker on Security and Defence, European Commission Dr Hans-Gert Pöttering Ambassador Ji r˘ í S˘ ediv´y Dr Peter Tauber Dr Karl von Wogau Robert Walter former President of the Permanent Represen- MP, Parliamentary State Secretary General of President of the European Parliament, tative of the Czech Secretary, German Federal the Kangaroo Group, -

Lessons Learned? the Evaluation of Desert Warfare and Amphibious Landing Practices in the German, British and Turkish Armies After 1918

Lessons Learned? The Evaluation of Desert Warfare and Amphibious Landing Practices in the German, British and Turkish Armies after 1918 Gerhard GRÜSSHABER Dr. phil., Munich/Germany E-Mail: [email protected] Geliş Tarihi: 03.03.2019 - Kabul Tarihi: 21.04.2019 ABSTRACT GRÜSSHABER, Gerhard, Lessons Learned? The Evaluation of Desert Warfare and Amphibious Landing Practices in the German, British and Turkish Armies After 1918, CTAD, Year 15, Issue 29 (Spring 2019), pp. 3-33. The article focuses on the question if and how the three belligerents of the First World War applied their military experiences gained in desert warfare and the conduct and defence of amphibious operations during the interwar years and the Second World War. This question is of particular relevance, since the conditions for the campaigns in North Africa (1940-43) and the invasion of northern France (1944) in many ways resembled those of the 1915-18 operations at Gallipoli as well as in the Sinai desert and in Palestine. The following article is an extended version of a chapter of the authorʼs dissertation The ‘German Spiritʼ in the Ottoman and Turkish Army, 1908-1938. A History of Military Knowledge Transfer, DeGruyter Oldenbourg, Berlin, 2018, pp. 180- 190. 4 Cumhuriyet Tarihi Araştırmaları Dergisi Yıl 15 Sayı 29 (Bahar 2019) Keywords: First World War; Gallipoli; D-Day; Afrikakorps; Second World War ÖZ GRÜSSHABER, Gerhard, Dersler Alınmış mı? Çöl Savaşının Değerlendirmesi ve Alman, İngiliz ve Türk Ordularında 1918 Sonrası Amfibik Çıkarma Uygulamaları, CTAD, Yıl 15, Sayı 29 (Bahar 2019), s. 3-33. Bu makale, iki dünya savaşı arası dönemde ve İkinci Dünya Savaşı sırasında Birinci Dünya Savaşı’nın üç muharibinin çöl savaşında edindikleri askeri deneyimler ile amfibik harekatın yürütülmesi ve savunulmasını uygulayıp uygulamadıkları sorusuna odaklanıyor. -

International Intervention and the Use of Force: Military and Police Roles

004SSRpaperFRONT_16pt.ai4SSRpaperFRONT_16pt.ai 1 331.05.20121.05.2012 117:27:167:27:16 SSR PAPER 4 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K International Intervention and the Use of Force: Military and Police Roles Cornelius Friesendorf DCAF DCAF a centre for security, development and the rule of law SSR PAPER 4 International Intervention and the Use of Force Military and Police Roles Cornelius Friesendorf DCAF The Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF) is an international foundation whose mission is to assist the international community in pursuing good governance and reform of the security sector. The Centre develops and promotes norms and standards, conducts tailored policy research, identifies good practices and recommendations to promote democratic security sector governance, and provides in‐country advisory support and practical assistance programmes. SSR Papers is a flagship DCAF publication series intended to contribute innovative thinking on important themes and approaches relating to Security Sector Reform (SSR) in the broader context of Security Sector Governance (SSG). Papers provide original and provocative analysis on topics that are directly linked to the challenges of a governance‐driven security sector reform agenda. SSR Papers are intended for researchers, policy‐makers and practitioners involved in this field. ISBN 978‐92‐9222‐202‐4 © 2012 The Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces EDITORS Alan Bryden & Heiner Hänggi PRODUCTION Yury Korobovsky COPY EDITOR Cherry Ekins COVER IMAGE © isafmedia The views expressed are those of the author(s) alone and do not in any way reflect the views of the institutions referred to or represented within this paper. -

Weapons Transfers and Violations of the Laws of War in Turkey

WEAPONS TRANSFERS AND VIOLATIONS OF THE LAWS OF WAR IN TURKEY Human Rights Watch Arms Project Human Right Watch New York AAA Washington AAA Los Angeles AAA London AAA Brussels Copyright 8 November 1995 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 95-81502 ISBN 1-56432-161-4 HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH Human Rights Watch conducts regular, systematic investigations of human rights abuses in some seventy countries around the world. It addresses the human rights practices of governments of all political stripes, of all geopolitical alignments, and of all ethnic and religious persuasions. In internal wars it documents violations by both governments and rebel groups. Human Rights Watch defends freedom of thought and expression, due process and equal protection of the law; it documents and denounces murders, disappearances, torture, arbitrary imprisonment, exile, censorship and other abuses of internationally recognized human rights. Human Rights Watch began in 1978 with the founding of its Helsinki division. Today, it includes five divisions covering Africa, the Americas, Asia, the Middle East, as well as the signatories of the Helsinki accords. It also includes five collaborative projects on arms transfers, children's rights, free expression, prison conditions, and women's rights. It maintains offices in New York, Washington, Los Angeles, London, Brussels, Moscow, Dushanbe, Rio de Janeiro, and Hong Kong. Human Rights Watch is an independent, nongovernmental organization, supported by contributions from private individuals and foundations worldwide. It accepts no government funds, directly or indirectly. The staff includes Kenneth Roth, executive director; Cynthia Brown, program director; Holly J. -

The German Military Mission to Romania, 1940-1941 by Richard L. Dinardo

The German Military Mission to Romania, 1940–1941 By RICHARD L. Di NARDO hen one thinks of security assistance and the train- ing of foreign troops, W Adolf Hitler’s Germany is not a country that typically comes to mind. Yet there were two instances in World War II when Germany did indeed deploy troops to other countries that were in noncombat cir- cumstances. The countries in question were Finland and Romania, and the German mili- tary mission to Romania is the subject of this article. The activities of the German mission to Romania are discussed and analyzed, and some conclusions and hopefully a few take- aways are offered that could be relevant for military professionals today. Creation of the Mission The matter of how the German military mission to Romania came into being can be covered relatively quickly. In late June 1940, the Soviet Union demanded from Romania the cession of both Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina. The only advice Germany could give to the Romanian government was to agree to surrender the territory.1 Fearful of further Soviet encroachments, the Roma- nian government made a series of pleas to Germany including a personal appeal from Wikimedia Commons King Carol II to Hitler for German military assistance in the summer of 1940. Hitler, Finnish Volunteer Battalion of German Waffen-SS return home from front in 1943 however, was not yet willing to undertake such a step. Thus, all Romanian requests were rebuffed with Hitler telling Carol that Romania brought its own problems upon itself by its prior pro-Allied policy. -

Romanian-German Relations Before and During the Holocaust

ROMANIAN-GERMAN RELATIONS BEFORE AND DURING THE HOLOCAUST Introduction It was a paradox of the Second World War that Ion Antonescu, well known to be pro- Occidental, sided with Germany and led Romania in the war against the Allies. Yet, Romania’s alliance with Germany occurred against the background of the gradually eroding international order established at the end of World War I. Other contextual factors included the re-emergence of Germany as a great power after the rise of the National Socialist government and the growing involvement of the Soviet Union in European international relations. In East Central Europe, the years following the First World War were marked by a rise in nationalism characterized by strained relations between the new nation-states and their ethnic minorities.1 At the same time, France and England were increasingly reluctant to commit force to uphold the terms of the Versailles Treaty, and the Comintern began to view ethnic minorities as potential tools in the “anti-imperialist struggle.”2 In 1920, Romania had no disputes with Germany, while its eastern border was not recognized by the Soviet Union. Romanian-German Relations during the Interwar Period In the early twenties, relations between Romania and Germany were dominated by two issues: the reestablishment of bilateral trade and German reparations for war damages incurred during the World War I German occupation. The German side was mainly interested in trade, whereas the Romanian side wanted first to resolve the conflict over reparations. A settlement was reached only in 1928. The Berlin government acted very cautiously at that time. -

German Army Map of Spain 1:50.000: 1940-1944

GERMAN ARMY MAP OF SPAIN 1: 50 000: 1940-1944 Scharfe, W. Freie Universitaet Berlin, Institut fuer Geographische Wissenschaften, Fachrichtung Kartographie, Malteserstr. 74-100, D - 12249 Berlin, Deutschland. Tel: 0049 - 30 - 838 70 330. Fax: 0049 - 30 - 838 70 760. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT During the Second World War the German Armed Forces produced a huge quantity of topographic map series covering real or possible combat areas in Europe, Africa and Asia by copying respective national map series. At the beginning these map series were named “Special edition” (Sonderausgabe), however, since summer 1943 “German Army Map” (Deutsche Heereskarte). The research on this giant map corpus is at its very start. A special historic and regional field concerns the German Army Map of Spain 1 : 50 000 - produced between 1940 and 1944 - which must be seen as a part of the German plan to capture Gibraltar and to bring Spain as a German ally into the Second World War. Via intelligence service connections between the German Armed Forces and the respective Spanish map authorities, which had survived the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939/Legion Condor), published maps as well as map proofs of the Mapa Nacional de España en escala de 1 : 50 000 were sent to the “Department of Wartime Map and Survey Service” (Abteilung für Kriegskarten-Karten- und -Vermessungswesen) - a depart-ment of the German General Staff of the Army. This department organized to copy the sheets and to add German labelling together with complete legends by map specialists of the “Army Map House” (Heeresplankammer). -

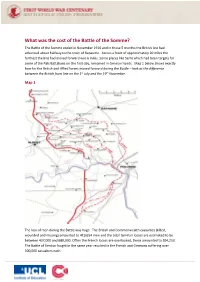

A Five Year Legacy Project Involving the Entire School

What was the cost of the Battle of the Somme? The Battle of the Somme ended in November 1916 and in those 5 months the British line had advanced about halfway to the town of Bapaume. Across a front of approximately 20 miles the furthest the line had moved forward was 6 miles. Some places like Serre which had been targets for some of the Pals Battalions on the first day, remained in German hands. Map 1 below shows exactly how far the British and Allied forces moved forward during the Battle – look at the difference between the British front line on the 1st July and the 19th November. Map 1 The loss of men during the Battle was huge. The British and Commonwealth casualties (killed, wounded and missing) amounted to 419,654 men and the total German losses are estimated to be between 437,000 and 680,000. Often the French losses are overlooked, these amounted to 204,253. The Battle of Verdun fought in the same year resulted in the French and Germans suffering over 300,000 casualties each. There was also an enormous personal cost – many villages, towns and cities in Britain were affected by the losses at the Battle of the Somme, especially communities that had raised Pals Battalions of volunteer soldiers. The cost of the Somme might be measured in other ways. In 1914 Britain’s National Debt amounted to £700 million, in July 1916 this had risen to £2,500 million. By the end of the War it had risen to £7,500 million.