Il Manuale Delle Stelle Variabili

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art and Culture

www.gradeup.co 1 www.gradeup.co Art and Culture GI tag to Manipur black rice, Gorakhpur terracotta Why in the news? • Recently Chinnaraja G. Naidu, Deputy Registrar, Geographical Indications, confirmed that the GI tag had been given for the two-products Manipur black rice and Gorakhpur terracotta. About Manipur black rice • It is also known as Chak-Hao (Black Rice). • It is scented glutinous rice, which has been in cultivation in Manipur over centuries, is characterized by its distinctive aroma. • It is usually eaten during community feasts and is served as Chak-Hao kheer. • Traditional medical practitioners have also used it as part of traditional medicine. • This rice takes the longest cooking time of 40-45 minutes due to the presence of a fibrous bran layer and higher crude fiber content. About Gorakhpur terracotta • It is a centuries-old traditional art form, where the potters make various animal figures like horses, elephants, camel, goat, and ox with hand-applied ornamentation. • Some of the major products of craftsmanship include the Hauda elephants, Mahawatdar horse, deer, camel, five-faced Ganesha, singled-faced Ganesha, elephant table, chandeliers, and hanging bells. What is Terracotta? • It is a type of ceramic pottery which is often used for pipes, bricks, and sculptures. 2 www.gradeup.co • Terracotta pottery is made by baking terracotta clay. • The terracotta color is a natural brown orange. What is a Geographical Indication? • A GI or Geographical Indication is a name, or a sign given to certain products that relate to a specific geographical location or origins like a region, town, or country. -

Download This Article in PDF Format

EPJ Web of Conferences 228, 00023 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/202022800023 mm Universe @ NIKA2 NIKA2 observations around LBV stars Emission from stars and circumstellar material 1,3, 2 1 J. Ricardo Rizzo ∗, Alessia Ritacco , and Cristobal Bordiu 1Centro de Astrobiología (CSIC-INTA), Ctra. M-108, km. 4, E-28850 Torrejón de Ardoz, Madrid, Spain 2Institut de Radioastronomie Milimétrique (IRAM), E-18012 Granada, Spain 3ISDEFE, Beatriz de Bobadilla 3, E-28040 Madrid, Spain Abstract. Luminous Blue Variable (LBV) stars are evolved massive objects, previous to core-collapse supernova. LBVs are characterized by photometric and spectroscopic variability, produced by strong and dense winds, mass-loss events and very intense UV radiation. LBVs strongly disturb their surroundings by heating and shocking, and produce important amounts of dust. The study of the circumstellar material is therefore crucial to understand how these massive stars evolve, and also to characterize their effects onto the interstellar medium. The versatility of NIKA2 is a key in providing simultaneous observations of both the stellar continuum and the extended, circumstellar contribution. The NIKA2 frequencies (150 and 260 GHz) are in the range where thermal dust and free-free emission compete, and hence NIKA2 has the capacity to provide key information about the spatial distribution of circumstellar ionized gas, warm dust and nearby dark clouds; non-thermal emission is also possible even at these high frequencies. We show the results of the first NIKA2 survey towards five LBVs. We detected emission from four stars, three of them immersed in tenuous circumstellar material. The spectral indices show a complex distribution and allowed us to separate and characterize different components. -

121012-AAS-221 Program-14-ALL, Page 253 @ Preflight

221ST MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY 6-10 January 2013 LONG BEACH, CALIFORNIA Scientific sessions will be held at the: Long Beach Convention Center 300 E. Ocean Blvd. COUNCIL.......................... 2 Long Beach, CA 90802 AAS Paper Sorters EXHIBITORS..................... 4 Aubra Anthony ATTENDEE Alan Boss SERVICES.......................... 9 Blaise Canzian Joanna Corby SCHEDULE.....................12 Rupert Croft Shantanu Desai SATURDAY.....................28 Rick Fienberg Bernhard Fleck SUNDAY..........................30 Erika Grundstrom Nimish P. Hathi MONDAY........................37 Ann Hornschemeier Suzanne H. Jacoby TUESDAY........................98 Bethany Johns Sebastien Lepine WEDNESDAY.............. 158 Katharina Lodders Kevin Marvel THURSDAY.................. 213 Karen Masters Bryan Miller AUTHOR INDEX ........ 245 Nancy Morrison Judit Ries Michael Rutkowski Allyn Smith Joe Tenn Session Numbering Key 100’s Monday 200’s Tuesday 300’s Wednesday 400’s Thursday Sessions are numbered in the Program Book by day and time. Changes after 27 November 2012 are included only in the online program materials. 1 AAS Officers & Councilors Officers Councilors President (2012-2014) (2009-2012) David J. Helfand Quest Univ. Canada Edward F. Guinan Villanova Univ. [email protected] [email protected] PAST President (2012-2013) Patricia Knezek NOAO/WIYN Observatory Debra Elmegreen Vassar College [email protected] [email protected] Robert Mathieu Univ. of Wisconsin Vice President (2009-2015) [email protected] Paula Szkody University of Washington [email protected] (2011-2014) Bruce Balick Univ. of Washington Vice-President (2010-2013) [email protected] Nicholas B. Suntzeff Texas A&M Univ. suntzeff@aas.org Eileen D. Friel Boston Univ. [email protected] Vice President (2011-2014) Edward B. Churchwell Univ. of Wisconsin Angela Speck Univ. of Missouri [email protected] [email protected] Treasurer (2011-2014) (2012-2015) Hervey (Peter) Stockman STScI Nancy S. -

Luminous Blue Variables: an Imaging Perspective on Their Binarity and Near Environment?,??

A&A 587, A115 (2016) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201526578 & c ESO 2016 Astrophysics Luminous blue variables: An imaging perspective on their binarity and near environment?;?? Christophe Martayan1, Alex Lobel2, Dietrich Baade3, Andrea Mehner1, Thomas Rivinius1, Henri M. J. Boffin1, Julien Girard1, Dimitri Mawet4, Guillaume Montagnier5, Ronny Blomme2, Pierre Kervella7;6, Hugues Sana8, Stanislav Štefl???;9, Juan Zorec10, Sylvestre Lacour6, Jean-Baptiste Le Bouquin11, Fabrice Martins12, Antoine Mérand1, Fabien Patru11, Fernando Selman1, and Yves Frémat2 1 European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere, Alonso de Córdova 3107, Vitacura, 19001 Casilla, Santiago de Chile, Chile e-mail: [email protected] 2 Royal Observatory of Belgium, 3 avenue Circulaire, 1180 Brussels, Belgium 3 European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere, Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 2, 85748 Garching b. München, Germany 4 Department of Astronomy, California Institute of Technology, 1200 E. California Blvd, MC 249-17, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 5 Observatoire de Haute-Provence, CNRS/OAMP, 04870 Saint-Michel-l’Observatoire, France 6 LESIA (UMR 8109), Observatoire de Paris, PSL, CNRS, UPMC, Univ. Paris-Diderot, 5 place Jules Janssen, 92195 Meudon, France 7 Unidad Mixta Internacional Franco-Chilena de Astronomía (CNRS UMI 3386), Departamento de Astronomía, Universidad de Chile, Camino El Observatorio 1515, Las Condes, Santiago, Chile 8 ESA/Space Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, MD 21218, -

Gaia Data Release 2 Special Issue

A&A 623, A110 (2019) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201833304 & © ESO 2019 Astrophysics Gaia Data Release 2 Special issue Gaia Data Release 2 Variable stars in the colour-absolute magnitude diagram?,?? Gaia Collaboration, L. Eyer1, L. Rimoldini2, M. Audard1, R. I. Anderson3,1, K. Nienartowicz2, F. Glass1, O. Marchal4, M. Grenon1, N. Mowlavi1, B. Holl1, G. Clementini5, C. Aerts6,7, T. Mazeh8, D. W. Evans9, L. Szabados10, A. G. A. Brown11, A. Vallenari12, T. Prusti13, J. H. J. de Bruijne13, C. Babusiaux4,14, C. A. L. Bailer-Jones15, M. Biermann16, F. Jansen17, C. Jordi18, S. A. Klioner19, U. Lammers20, L. Lindegren21, X. Luri18, F. Mignard22, C. Panem23, D. Pourbaix24,25, S. Randich26, P. Sartoretti4, H. I. Siddiqui27, C. Soubiran28, F. van Leeuwen9, N. A. Walton9, F. Arenou4, U. Bastian16, M. Cropper29, R. Drimmel30, D. Katz4, M. G. Lattanzi30, J. Bakker20, C. Cacciari5, J. Castañeda18, L. Chaoul23, N. Cheek31, F. De Angeli9, C. Fabricius18, R. Guerra20, E. Masana18, R. Messineo32, P. Panuzzo4, J. Portell18, M. Riello9, G. M. Seabroke29, P. Tanga22, F. Thévenin22, G. Gracia-Abril33,16, G. Comoretto27, M. Garcia-Reinaldos20, D. Teyssier27, M. Altmann16,34, R. Andrae15, I. Bellas-Velidis35, K. Benson29, J. Berthier36, R. Blomme37, P. Burgess9, G. Busso9, B. Carry22,36, A. Cellino30, M. Clotet18, O. Creevey22, M. Davidson38, J. De Ridder6, L. Delchambre39, A. Dell’Oro26, C. Ducourant28, J. Fernández-Hernández40, M. Fouesneau15, Y. Frémat37, L. Galluccio22, M. García-Torres41, J. González-Núñez31,42, J. J. González-Vidal18, E. Gosset39,25, L. P. Guy2,43, J.-L. Halbwachs44, N. C. Hambly38, D. -

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Nachlass EDUARD SCHÖNFELD (1828-1891) Inhaltsverzeichnis Bearbeitet von Anne Hoffsümmer und Lea Korb Bonn, 2017 – 2018 zuletzt aktualisiert am 09.09.2020 Eduard Schönfeld wurde am 22.12.1828 in Hildburghausen geboren, wo er bis zu seinem Abitur 1847 die Schule besuchte. Er war Kind einer jüdischen Familie, trat jedoch nach seinem Schulabschluss dem evangelischen Glauben bei. Auf Anraten seines Vaters studierte Schönfeld zunächst Bauwesen, entschied sich aber nach kurzer Zeit für die Naturwissenschaften und begann, in Marburg bei dem Gauß-Schüler Christian Ludwig Gerling unter anderem Astronomie zu studieren. Nachdem Schönfeld auf einer Reise nach Bonn Bekanntschaft mit Friedrich Wilhelm August Argelander gemacht hatte, entschloss er sich, das Studium der Astronomie 1852 in Bonn fortzusetzen. Dort erhielt er schon ein Jahr später eine Stelle als Assistent, durch die er die Möglichkeit erhielt, gemeinsam mit Adalbert Krüger an der bekannten „Bonner Durchmusterung“, Argelanders großem Projekt, mitzuwirken. Mit einer Abhandlung über die Bahnelemente des Kleinplaneten Thetis promovierte Schönfeld 1854. Seine Habilitation folgte drei Jahre später. Eduard Schönfeld zog 1859 nach Mannheim, um dort die Stelle als Direktor der Mannheimer Sternwarte anzutreten. In der Mannheimer Zeit widmete er sich unter anderem der Bestimmung der Positionen von Nebelflecken mithilfe des Ringmikrometer. Eduard Schönfeld war Mitbegründer und Vorstandsmitglied der Astronomischen Gesellschaft sowie lange Jahre ihr Schriftführer und Herausgeber der Vierteljahrsschrift. Nach Argelanders Tod im Jahr 1875 übernahm Schönfeld dessen Stelle als Direktor der Bonner Sternwarte und ergänzte die Arbeit zur Bonner Durchmusterung, indem er die Bereiche -2°- -23° der südlichen Deklination erforschte. 1883 wurde er Geheimer Regierungsrat und war 1887/88 Rektor der Universität Bonn. -

Ejections De Mati`Ere Par Les Astres : Des Étoiles Massives Aux Quasars

Universite´ de Liege` Faculte´ des Sciences Ejections de matiere` par les astres : des etoiles´ massives aux quasars par Damien HUTSEMEKERS Docteur en Sciences Chercheur Qualifie´ du FNRS Dissertation present´ ee´ en vue de l’obtention du grade d’Agreg´ e´ de l’Enseignement Superieur´ 2003 Illustration de couverture : la n´ebuleuse du Crabe, constitu´ee de gaz ´eject´e`agrande vitesse par l’explosion d’une ´etoile en supernova. Clich´eobtenu avec le VLT et FORS2, ESO, 1999. Table des matieres` Preface´ et remerciements 5 Introduction 7 Articles 21 I Les nebuleuses´ eject´ ees´ par les etoiles´ massives 23 1 HR Carinae : a Luminous Blue Variable surrounded by an arc-shaped nebula 25 2 The nature of the nebula associated with the Luminous Blue Variable star WRA751 37 3 A dusty nebula around the Luminous Blue Variable candidate HD168625 45 4 Evidence for violent ejection of nebulae from massive stars 57 5 Dust in LBV-type nebulae 63 II Quasars de type BAL et microlentilles gravitationnelles 73 6 The use of gravitational microlensing to scan the structureofBALQSOs 75 7 ESO & NOT photometric monitoring of the Cloverleaf quasar 89 8 Selective gravitational microlensing and line profile variations in the BAL quasar H1413+117 99 9 An optical time-delay for the lensed BAL quasar HE2149-2745 113 3 III Quasars de type BAL : polarisation 127 10 A procedure for deriving accurate linear polarimetric measurements 129 11 Optical polarization of 47 quasi-stellar objects : the data 137 12 Polarization properties of a sample of Broad Absorption Line and gravitatio- -

Pulsating Variable Stars and the Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram

- !% ! $1!%" % Studying intrinsically pulsating variable stars plays a very important role in stellar evolution under- standing. The Hertzsprung-Russell diagram is a powerful tool to track which stage of stellar life is represented by a particular type of variable stars. Let's see what major pulsating variable star types are and learn about their place on the H-R diagram. This approach is very useful, as it also allows to make a decision about a variability type of a star for which the properties are known partially. The Hertzsprung-Russell diagram shows a group of stars in different stages of their evolution. It is a plot showing a relationship between luminosity (or abso- lute magnitude) and stars' surface temperature (or spectral type). The bottom scale is ranging from high-temperature blue-white stars (left side of the diagram) to low-temperature red stars (right side). The position of a star on the diagram provides information about its present stage and its mass. Stars that burn hydrogen into helium lie on the diagonal branch, the so-called main sequence. In this article intrinsically pulsating variables are covered, showing their place on the H-R diagram. Pulsating variable stars form a broad and diverse class of objects showing the changes in brightness over a wide range of periods and magnitudes. Pulsations are generally split into two types: radial and non-radial. Radial pulsations mean the entire star expands and shrinks as a whole, while non- radial ones correspond to expanding of one part of a star and shrinking the other. Since the H-R diagram represents the color-luminosity relation, it is fairly easy to identify not only the effective temperature Intrinsic variable types on the Hertzsprung–Russell and absolute magnitude of stars, but the evolutionary diagram. -

Variable Star

Variable star A variable star is a star whose brightness as seen from Earth (its apparent magnitude) fluctuates. This variation may be caused by a change in emitted light or by something partly blocking the light, so variable stars are classified as either: Intrinsic variables, whose luminosity actually changes; for example, because the star periodically swells and shrinks. Extrinsic variables, whose apparent changes in brightness are due to changes in the amount of their light that can reach Earth; for example, because the star has an orbiting companion that sometimes Trifid Nebula contains Cepheid variable stars eclipses it. Many, possibly most, stars have at least some variation in luminosity: the energy output of our Sun, for example, varies by about 0.1% over an 11-year solar cycle.[1] Contents Discovery Detecting variability Variable star observations Interpretation of observations Nomenclature Classification Intrinsic variable stars Pulsating variable stars Eruptive variable stars Cataclysmic or explosive variable stars Extrinsic variable stars Rotating variable stars Eclipsing binaries Planetary transits See also References External links Discovery An ancient Egyptian calendar of lucky and unlucky days composed some 3,200 years ago may be the oldest preserved historical document of the discovery of a variable star, the eclipsing binary Algol.[2][3][4] Of the modern astronomers, the first variable star was identified in 1638 when Johannes Holwarda noticed that Omicron Ceti (later named Mira) pulsated in a cycle taking 11 months; the star had previously been described as a nova by David Fabricius in 1596. This discovery, combined with supernovae observed in 1572 and 1604, proved that the starry sky was not eternally invariable as Aristotle and other ancient philosophers had taught. -

Among the Intrinsic Variables, the RV Tauri Stars Days

496 ASTRONOMY: PA YNE-GAPOSCHKIN AND BRENTON PROC. N. A. S. A STUDY OF THE RV TAURI VARIABLES By CECILIA PAYNE-GAPOSCHKIN AND VIRGINIA K. BRENTON HARVARD COLLEGE OBSERVATORY Communicated October 16, 1942 1. Definitions.-Among the intrinsic variables, the RV Tauri stars stand out with rather definite characteristics. Three principal criteria may be used for assigning stars to the class. (a) Successive minima differ in depth. Deep and shallow minima are conventionally called "primary" and "secondary." (b) Primary and secondary minima interchange phases at intervals. (c) The stars are variable in spectrum and in radial velocity. The spectrum is of Class F, G or K at maximum. The shortest known period is 38 days (EZ Aquilae), the longest is 146 days (R Scuti). Although the period usually assigned to these stars is that from one primary minimum to the next, a comparison with the velocity curve shows that the star undergoes a type of pulsation with one-half that period. The brighter RV Tauri stars have recently been studied on the Harvard collection of stellar photographs. Of the twenty-nine stars now assigned to the class, fourteen proved to be bright enough for intensive study. A discussion of about sixteen thousand observations of these stars has been completed,' and the present note is intended to summarize some of the physical results. 2. The Secondary Characteristics.-Many RV Tauri stars show rather marked irregularities in period, and though over a long interval a mean period can always be assigned, instantaneous elements for short intervals may require periods differing by one or two per cent. -

Variabelbulletinen Nr. 1

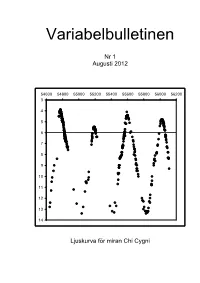

Variabelbulletinen Nr 1 Augusti 2012 54600 54800 55000 55200 55400 55600 55800 56000 56200 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Ljuskurva för miran Chi Cygni 2 Variabelbulletinen Nr 1. Augusti 2012. ISSN 2001-3930 En publikation från Svensk AmatörAstronomisk Förening Variabelsektionen (SAAF/V) Sektionsledare Chris Allen Ansvariga för databasen SVO Thomas Karlsson och Robert Wahlström Redaktör Hans Bengtsson Icke signerat material har författats av redaktören. Innehållsförteckning Introduktion. …………………...…………………………………………………………………….……………………….…… 4 Hans Bengtsson: Klassiska miror och legendariska variabilister. ………………...…….…..... 4 Thomas Karlsson: Epsilon Aurigae. ….……………………...……………………………...………………..…. 16 Hans Bengtsson: Våra variabler. Första delen. ………………………………………..…….....….……. 16 Thomas Karlsson: Ljusstark supernova i M101. ………………………………………………..…….… 26 Gustav Holmberg: Några RCB-stjärnor säsongen 2011-2012. …....…………...……….……. 28 Thomas Karlsson: Bestämning av period för 58 variabler. …………..……………...……….…... 31 Thomas Karlsson: Maxima för miror. ………………………………………………………………...……….… 33 Thomas Karlsson: Fotometri i Sagitta och Vulpecula. …………………………………………….… 34 Statistisk från SVO. ……………..…………………………………………...………………………………………...…… 38 Hans Bengtsson: Variabelmöten – en ny tradition. …………...……………………………………….. 39 Hans Bengtsson: Flera flugor i samma smäll. …………………………...............................…………... 40 Förstasidan Ljuskurva för miran Chi Cygni. Följande observatörer har bidragit till diagrammet: Chris Allen (45), Hans Bengtsson (102), Göran Fredriksson (9), -

A a Averages Aberration – Annual – Constant – Diurnal – of Starlight Absolut

Index A appearance APQ triplet A averages Arago Point aberration arclet , , –annual arcs , –constant area measurement –diurnal area number , –ofstarlight –Beck absolute magnitude armillary sphere Absorption Av ASCOM achromat ASCOM driver active galaxy , , , Association of Lunar and Planetary Observers active nuclei , active solar regions asteroid , activity center , –absolutemagnitude –development – asteroid family activity cycle –lightcurve activity herd –oppositioneffect adaptive Laplace filtering , –phasefunction afocal – polarimetry air mass –spectroscopy Airy disk –visualbrightness albedo Asteroid Belt Alt-Azimuthal asteroid profile amateur asteroid-like appearance –astronomer asteroid-like comet –observer astigmatism – working group astrometric data reduction amateur–professional partnership , astrometry of asteroids American Association of Variable Star Observers astronomical education , , –hands-onastronomy –SolarDivision – in the classroom Andromeda Nebula –planetarium () Annefrank , – public observatory annular eclipse , , , – science museum annular/total eclipse – societies and organizations anti-tail , astronomical research antireflection coating astronomical societies aperture photometry Astronomical Society of the Pacific aperture stop astronomy aphelion astronomy day () APL , astronomy olympiad apochromat astronomy vacation , Apollo astrophotography Apollo shock asymptotic (or second) giant branch (AGB) apparition light curve atmosphere of