Kanban Implementation from a Change Management Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Implementation of Kanban, a Lean Tool, in Switchgear Manufacturing Industry – a Case Study

Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management Paris, France, July 26-27, 2018 Implementation of Kanban, a Lean tool, In Switchgear Manufacturing Industry – A Case Study Shashwat Gawande College Of Engineering, Pune Department of Industrial Engineering and management Savitribai Phule Pune University Pune, Maharashtra 44, India [email protected] Prof. J.S Karajgikar College Of Engineering, Pune Department of Industrial Engineering and management Savitribai Phule Pune University Pune, Maharashtra 44, India [email protected] Abstract Kanban is a scheduling system for lean and just in time manufacturing industries or services firms. It is a very effective tool for running a production system as a whole, in this system problem areas are highlighted by measuring lead time and cycle time of the full process the other benefits of the Kanban system is to establish an upper limit to work in process inventory to avoid over capacity. The objective of this case study is to implement a standard Kanban System for a Electrical manufacturing MNC company. With this system, the firm implemented use of just in time to reduce the inventory cost stocked during the process. This case study also shows that the Kanban implementation is not only bounded to the company but to their vendor also, from where, some of the components are been assembled. A replenishment strategy was also developed, tested and improved at the company location. A complete instruction manual is also developed as a reference Keywords Value Steam Mapping, Kanban, Root Cause Analysis, Replenishment Strategy 1. Introduction Lean manufacturing or simply ‘lean’ is a systematic method for waste reduction within a manufacturing system without affecting productivity. -

Material Replenishment System

MATERIAL REPLENISHMENT SYSTEM REPLENISHMENT METHODS FOR VISUALIZING MATERIAL NEEDS IN A LEAN MANUFACTURING COMPANY Examensarbete – Högskoleingenjör Industriell ekonomi Stefan Andersson Johan Elfvenfrost År: 2016.18.07 I Svensk titel: Material återfyllningssystem Engelsk titel: Material replenishment system Utgivningsår: 2016 Författare: Stefan Andersson, Johan Elfvenfrost Handledare: Sara Lorén, Högskolan i Borås Magnus Hansson Fallenius, IAC Group Göteborg Examinator: Andreas Hagen II Abstract This thesis work has been written both for and in co-operation with the company IAC Group Gothenburg. The main purpose of the report is to find a new alternative material replenishment system which will improve the internal material flow and eliminate unnecessary work activities such as manual call offs. The aim is to find a new system to reduce the incidental costs incurred and improve customer service in quality and performance. Observations and interviews were conducted and an analysis of the current situation was made. Waste was identified in the form of unnecessary transport, specifically in milk runs, where time was spent looking for materials to be loaded. This creates uncertainty and may contribute to increased costs and poor customer service. Three different options for a new replenishment system were developed which were compared with the theory and present situation. The proposal was evaluated with respect to cost, available support, complexity and future compatibility. The analysis of the theory and current state shows the importance of a long-term solution with few risks of waste. The solution that best cope with this is an e-Kanban system that automates the replenishment system and would make manual material call offs disappear completely. -

APPLICATION of KANBAN SYSTEM for IMPLEMENTING LEAN MANUFACTURING (A CASE STUDY) 1 2 3 B.Vijaya Ramnath, C

Journal of Engineering Research and Studies Research Article APPLICATION OF KANBAN SYSTEM FOR IMPLEMENTING LEAN MANUFACTURING (A CASE STUDY) 1 2 3 B.Vijaya Ramnath, C. Elanchezhian and R. Kesavan Address for Correspondence 1,2 Research Scholar, 3Asst. Professor, Department of Production Technology, Anna University, MIT Campus, Chennai-44, Tamilnadu Email: [email protected] ====================================================================== ABSTRACT This paper deals with implementation of lean manufacturing in Engine valve machining cell in a leading auto components manufacturing industry in the South India. The main objective of this paper is to provide a background on lean manufacturing, present an overview of manufacturing wastes and introduce the tools and techniques that are used to transform a company into a high performing lean enterprise. Value stream mapping is a main tool used to identify the opportunities for various lean techniques. The focus of the lean manufacturing approach is on cost reduction by eliminating Non- Value added activities. Applications have spanned many sectors including automotive, electronics and consumer products manufacturing. In this paper, Value Stream Mapping (VSM) is used to map the current operating state for production line. This map is used to identify sources of waste and to identify lean tools for reducing the waste. To eliminate the wastes found from the current state map Kanban system is suggested for pre machining section and single piece flow concept is suggested for machining section. Then a future state map has been developed for the system with lean tools applied to it KEYWORDS: Lean manufacturing, Value Stream Mapping and Kanban System 1. INTRODUCTION system focused on and driven by customers, Many manufacturers are now critically both internal and external. -

A Framework of E-Kanban System for Indonesia Automotive Mixed-Model Production Line

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN: 2319-7064 ResearchGate Impact Factor (2018): 0.28 | SJIF (2018): 7.426 A Framework of e-Kanban System for Indonesia Automotive Mixed-Model Production Line Santo Wijaya1, Fransisca Debora2, Galih Supriadi3, Insan Ramadhan4 1Department of Computer Engineering, META Industry of Polytechnic, Cikarang Technopark Building, Lippo Cikarang, West Java 17550, Indonesia 2Department of Industrial Engineering, META Industry of Polytechnic, Cikarang Technopark Building, Lippo Cikarang, West Java 17550, Indonesia 3PT. Trimitra Chitrahasta, Delta Silicon 2 Industrial Estate, West Java 17530, Indonesia 4Agency for the Assessment and Application of Technology, Puspiptek Serpong, Indonesia Abstract: The paper describes a development framework of e-Kanban (electronic Kanban) system for Indonesia automotive mixed- model production line. It is intended to solve problems found during the implementation of traditional kanban system in the subjected company. The traditional kanban system posed inefficiencies in the production line and it has been identified in this paper. The impact is significant in causing delay information for production instruction, loss of kanban cards, inaccurate inventory, and other human- related errors. We also identified that these inefficiencies are also increasing with the increase of product variety and volume in mixed- model production line. The presented framework is the extension of the traditional kanban system that has been running for over one year in the subject company. Design framework objective is to handle all the inefficiencies problem occurred and improve the overall efficiency of material and information flow within the production line. It is a combination of paper-based kanban and software-based kanban system. Paper-based kanban handles the movement of man and material in the production line. -

Bringing Lean to Life: Making Processes Flow in Healthcare

NH S Improving Quality BRINGING LEAN TO LIFE Making processes flow in healthcare IMPROVEMENT. PEOPLE. QUALITY. STAFF. DATA. SATcEknPoSw.leLdgEeAmNen. tsPATIENTS. PRODUCTIVITY. IDEAS. This document has been written in partnership by: RZEoë LDord ESIGN. MAPPING. SOLUTIONS. EXPERIENCE. Email: [email protected] Lisa Smith SEmHail:A [email protected] OCESSES. TOOLS. MEASURES. INVOLVEMENT. STRENGTH. SUPPORT. LEARN. CHANGE. TEST. IMPLEMENT. PREPARATION. KNOW-HOW. SCOPE. INNOVATION. FOCUS. ENGAGEMENT. DELIVERY. DIAGNOSIS. LAUNCH. RESOURCES. EVALUATION. NHS. PLANNING. TECHNIQUES. FRAMEWORK. AGREEMENT. UNDERSTAND. IMPLEMENTATION. SUSTAIN. Bringing Lean to Life - Making processes flow in healthcare Contents Introduction - what is the problem in healthcare? 4 Identifying waste 18 What is Lean? 6 Making value flow 21 A3 thinking 7 Understanding pull 22 An example A3 report 8 Understanding Takt time 23 The importance of data and measures 10 Using 5S to improve safety 24 Example statistical process control (SPC) charts 11 Plan, Do, Check, Adjust (PDCA) cycle 25 Current state value stream mapping 12 Continuous improvement 26 Analysing your current state and designing your 14 Value stream mapping symbols 27 future state value stream map Standard work to produce high quality every time 15 Visual management 16 3 4 Bringing Lean to Life - Making processes flow in healthcare Introduction - what is the problem in healthcare? We all come to work to do our very best - to The processes are to blame, not the people This booklet provides a basic introduction and achieve what we are capable of and to add real overview of Lean; the culture, principles and value for our patients and ensure clinical Often, there is ambiguity in how certain tasks tools to understand to enable you to tackle and expertise is supported by process excellence to should be performed – so people work it out for resolve issues within healthcare. -

Takt Time Grouping: a Method to Implement Kanban-Flow Manufacturing in an Unbalanced Process with Moving Constraints Mitchell Alan Millstein University of Missouri-St

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Dissertations UMSL Graduate Works 7-6-2014 Takt Time Grouping: A Method to Implement Kanban-Flow Manufacturing in an Unbalanced Process with Moving Constraints Mitchell Alan Millstein University of Missouri-St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation Part of the Business Commons Recommended Citation Millstein, Mitchell Alan, "Takt Time Grouping: A Method to Implement Kanban-Flow Manufacturing in an Unbalanced Process with Moving Constraints" (2014). Dissertations. 242. https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation/242 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the UMSL Graduate Works at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Takt Time Grouping A Method to Implement Kanban-Flow Manufacturing in an Unbalanced Process with Moving Constraints & Comparison to One Piece Flow and Drum Buffer Rope: Which is Better, When and Why Mitchell A. Millstein M.B.A, Washington University – St. Louis, MO, 1996 B.S., Engineering, Rutgers University – New Brunswick, NJ, 1988 A Thesis Submitted to The Graduate School at the University of Missouri – St. Louis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Ph.D. in Business Administration with an emphasis in Logistics and Supply Chain Management Advisory Committee Joseph P. Martinich, Ph.D. Chairperson Robert M. Nauss, Ph.D. L. Douglas Smith, Ph.D. Donald C. Sweeney II, Ph.D. Revision: July 2, 2014 Copyright, Mitchell A. Millstein, 2014 1 Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................................... 7 Section 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................................ -

Toyota Production System Toyota Production System

SNS COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AN AUTONOMOUS INSTITUTION Kurumbapalayam (Po), Coimbatore – 641 107 Accredited by NBA – AICTE and Accredited by NAAC – UGC with ‘A’ Grade Approved by AICTE, New Delhi & Affiliated to Anna University, Chennai TOYOTA PRODUCTION SYSTEM 1 www.a2zmba.com Vision Contribute to Indian industry and economy through technology transfer, human resource development and vehicles that meet global standards at competitive price. Contribute to the well-being and stability of team members. Contribute to the overall growth for our business associates and the automobile industry. 2 www.a2zmba.com Mission Our mission is to design, manufacture and market automobiles in India and overseas while maintaining the high quality that meets global Toyota quality standards, to offer superior value and excellent after-sales service. We are dedicated to providing the highest possible level of value to customers, team members, communities and investors in India. www.a2zmba.com 3 7 Principles of Toyota Production System Reduced setup time Small-lot production Employee Involvement and Empowerment Quality at the source Equipment maintenance Pull Production Supplier involvement www.a2zmba.com 4 Production System www.a2zmba.com 5 JUST-IN-TIME Produced according to what needed, when needed and how much needed. Strategy to improve return on investment by reducing inventory and associated cost. The process is driven by Kanban concept. www.a2zmba.com 6 KANBAN CONCEPT Meaning- Sign, Index Card It is the most important Japanese concept opted by Toyota. Kanban systems combined with unique scheduling tools, dramatically reduces inventory levels. Enhances supplier/customer relationships and improves the accuracy of manufacturing schedules. A signal is sent to produce and deliver a new shipment when material is consumed. -

How Synckanban Addresses the 8 Types of Waste in Lean

SYNCHRONO THOUGHT LEADERSHIP Forms of Waste 8 in Lean Manufacturing How SyncKanban™ Software Addresses the 8 Types of Waste in Lean At the heart of lean manufacturing is one very simple principle: remove as much waste as possible from your processes. Waste is specifically defined as anything that doesn’t add value to the customer. When the lean manufacturing philosophy was first introduced, the Toyota Production System (TPS) founder, Taiichi Ohno, identified seven types of waste. Since then, lean thinkers have added one to give us the eight types of waste we focus on today: 1. Overproduction 2. Waiting 3. Inventory 4. Transportation 5. Over-processing 6. Motion 7. Defects 8. Workforce 1 8 FORMS OF WASTE IN LEAN MANUFACTURING There are many ways to eliminate these eight forms of waste, from costly and time-consuming initiatives focused on redesigning the factory floor to an afternoon spent cleaning and organizing a work center. When comparing the level of effort to potential return, implementing eKanban is one of the most attractive lean initiatives there is. Manufacturers we’ve worked with have increased inventory turns by as much as 91% and cut inventory costs in half through eKanban initiatives that took less than three months to implement – and that includes training employees on the new processes and procedures. In this paper, we’ll discuss how SyncKanbanTM eKanban software from Synchrono can help you address all eight forms of waste to help you reach your lean goals this year. Below are definitions of several terms that you will find referenced in this paper. -

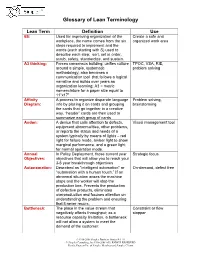

Glossary of Lean Terminology

Glossary of Lean Terminology Lean Term Definition Use 6S: Used for improving organization of the Create a safe and workplace, the name comes from the six organized work area steps required to implement and the words (each starting with S) used to describe each step: sort, set in order, scrub, safety, standardize, and sustain. A3 thinking: Forces consensus building; unifies culture TPOC, VSA, RIE, around a simple, systematic problem solving methodology; also becomes a communication tool that follows a logical narrative and builds over years as organization learning; A3 = metric nomenclature for a paper size equal to 11”x17” Affinity A process to organize disparate language Problem solving, Diagram: info by placing it on cards and grouping brainstorming the cards that go together in a creative way. “header” cards are then used to summarize each group of cards Andon: A device that calls attention to defects, Visual management tool equipment abnormalities, other problems, or reports the status and needs of a system typically by means of lights – red light for failure mode, amber light to show marginal performance, and a green light for normal operation mode. Annual In Policy Deployment, those current year Strategic focus Objectives: objectives that will allow you to reach your 3-5 year breakthrough objectives Autonomation: Described as "intelligent automation" or On-demand, defect free "automation with a human touch.” If an abnormal situation arises the machine stops and the worker will stop the production line. Prevents the production of defective products, eliminates overproduction and focuses attention on understanding the problem and ensuring that it never recurs. -

Lean Manufacturing Techniques for Textile Industry Copyright © International Labour Organization 2017

Lean Manufacturing Techniques For Textile Industry Copyright © International Labour Organization 2017 First published (2017) Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Licensing), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with a reproduction rights organization may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. ILO Cataloging in Publication Data/ Lean Manufacturing Techniques for Textile Industry ILO Decent Work Team for North Africa and Country Office for Egypt and Eritrea- Cairo: ILO, 2017. ISBN: 978-92-2-130764-8 (print), 978-92-2-130765-5 (web pdf) The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. The responsibility for opinions expressed in signed articles, studies and other contributions rests solely with their authors, and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the International Labour Office of the opinions expressed in them. Reference to names of firms and commercial products and processes does not imply their endorsement by the International Labour Office, and any failure to mention a particular firm, commercial product or process is not a sign of disapproval. -

Developing and Building a Lean Based Rfid Electronic

DEVELOPING AND BUILDING A LEAN BASED RFID ELECTRONIC KANBAN PROTOTYPE A Thesis presented to The Faculty of California Polytechnic State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Industrial Engineering by Ryan T. Chang June 2012 © 2012 Ryan Chang ALL RIGHTS RESERVED COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP ii TITLE DEVELOPING AND BUILDING A LEAN BASED RFID ELECTRONIC KANBAN PROTOTYPE AUTHOR: Ryan T. Chang DATE SUBMITTED: June 2012 COMMITTEE CHAIR: Dr. Tali Freed, Professor, Industrial and Manufacturing Engineering COMMITTEE MEMBER: Dr. Lizabeth Schlemer, Associate Professor, Industrial and Manufacturing Engineering COMMITTEE MEMBER: Dr. Tao Yang, Professor, Industrial and Manufacturing Engineering ABSTRACT DEVELOPING AND BUILDING A LEAN BASED iii RFID ELECTRONIC KANBAN PROTOTYPE Ryan T. Chang The kanban system is a popular Toyota lean manufacturing tool used to help facilitate material movement between workstations and suppliers. Since the 1950’s, the original kanban system has undergone many different variations due to the advancement of technology and unique company implementation. This report focuses on the development and building of a new variation of the kanban system using lean principles while integrating radio frequency identification (RFID) technology with a fully electronic based kanban card system. This new type of kanban system will be called the RFID E-Kanban in this report. Since the lean philosophy is to reduce non-value added waste to a process, the new prototype kanban system meets four design objectives that are consistent with the principles of lean and the original purpose of the kanban system. 1. The RFID E-Kanban prototype must support the process of continuous improvement 2. -

Simpler, Faster, Better, Less Costly - Lean.Ohio.Gov

Day 3 Simpler, Faster, Better, Less Costly - Lean.Ohio.gov REVIEW ACTIVITY What You Choose to Remember • Groups of 3 • What you Chose to Remember from Days #1 & #2 • Everyone Contributes Simpler, Faster, Better, Less Costly - Lean.Ohio.gov 3-3 OVERVIEW What We Will Cover • Poka Yoke, Pareto Diagram • Batching-Single Piece Flow • Push-Pull • Standardized Work • Kanban • Brainstorming, Affinity Diagram, Impact-Control Matrix • Clean Sheet Redesign Simpler, Faster, Better, Less Costly - Lean.Ohio.gov 3-4 Poka Yoke POKA YOKE “Mistake Proofing” Simpler, Faster, Better, Less Costly - Lean.Ohio.gov 3-6 POKA YOKE * TypicalPoka Yoke Reactions: “What ancan idiot!” we do to prevent that mistake from ever happening again?”“Most people know enough to remove the hose before they drive off - why should we change things for one fool?” “There’s just nothing that can be done to help some people” Simpler, Faster, Better, Less Costly - Lean.Ohio.gov 3-7 POKA YOKE * Simpler, Faster, Better, Less Costly - Lean.Ohio.gov 3-8 POKA YOKE * Simpler, Faster, Better, Less Costly - Lean.Ohio.gov 3-9 POKA YOKE Simpler, Faster, Better, Less Costly - Lean.Ohio.gov 3-10 POKA YOKE * 3-11 Simpler, Faster, Better, Less Costly - Lean.Ohio.gov POKA YOKE * Simpler, Faster, Better, Less Costly - Lean.Ohio.gov 3-12 POKA YOKE: RAILROAD CROSSING SAFETY 3-13 Simpler, Faster, Better, Less Costly - Lean.Ohio.gov POKA YOKE: RAILROAD CROSSING SAFETY Simpler, Faster, Better, Less Costly - Lean.Ohio.gov 3-14 POKA YOKE: RAILROAD CROSSING SAFETY Simpler, Faster, Better, Less Costly - Lean.Ohio.gov