2020 Report on the Health of Colorado's Forests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colorado Fourteeners Checklist

Colorado Fourteeners Checklist Rank Mountain Peak Mountain Range Elevation Date Climbed 1 Mount Elbert Sawatch Range 14,440 ft 2 Mount Massive Sawatch Range 14,428 ft 3 Mount Harvard Sawatch Range 14,421 ft 4 Blanca Peak Sangre de Cristo Range 14,351 ft 5 La Plata Peak Sawatch Range 14,343 ft 6 Uncompahgre Peak San Juan Mountains 14,321 ft 7 Crestone Peak Sangre de Cristo Range 14,300 ft 8 Mount Lincoln Mosquito Range 14,293 ft 9 Castle Peak Elk Mountains 14,279 ft 10 Grays Peak Front Range 14,278 ft 11 Mount Antero Sawatch Range 14,276 ft 12 Torreys Peak Front Range 14,275 ft 13 Quandary Peak Mosquito Range 14,271 ft 14 Mount Evans Front Range 14,271 ft 15 Longs Peak Front Range 14,259 ft 16 Mount Wilson San Miguel Mountains 14,252 ft 17 Mount Shavano Sawatch Range 14,231 ft 18 Mount Princeton Sawatch Range 14,204 ft 19 Mount Belford Sawatch Range 14,203 ft 20 Crestone Needle Sangre de Cristo Range 14,203 ft 21 Mount Yale Sawatch Range 14,200 ft 22 Mount Bross Mosquito Range 14,178 ft 23 Kit Carson Mountain Sangre de Cristo Range 14,171 ft 24 Maroon Peak Elk Mountains 14,163 ft 25 Tabeguache Peak Sawatch Range 14,162 ft 26 Mount Oxford Collegiate Peaks 14,160 ft 27 Mount Sneffels Sneffels Range 14,158 ft 28 Mount Democrat Mosquito Range 14,155 ft 29 Capitol Peak Elk Mountains 14,137 ft 30 Pikes Peak Front Range 14,115 ft 31 Snowmass Mountain Elk Mountains 14,099 ft 32 Windom Peak Needle Mountains 14,093 ft 33 Mount Eolus San Juan Mountains 14,090 ft 34 Challenger Point Sangre de Cristo Range 14,087 ft 35 Mount Columbia Sawatch Range -

San Juan National Forest

SAN JUAN NATIONAL FOREST Colorado UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE V 5 FOREST SERVICE t~~/~ Rocky Mountain Region Denver, Colorado Cover Page. — Chimney Rock, San Juan National Forest F406922 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1942 * DEPOSITED BY T,HE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA San Juan National Forest CAN JUAN NATIONAL FOREST is located in the southwestern part of Colorado, south and west of the Continental Divide, and extends, from the headwaters of the Navajo River westward to the La Plata Moun- \ tains. It is named after the San Juan River, the principal river drainage y in this section of the State, which, with its tributaries in Colorado, drains the entire area within the forest. It contains a gross area of 1,444,953 ^ acres, of which 1,255,977 are Government land under Forest Service administration, and 188,976 are State and privately owned. The forest was created by proclamation of President Theodore Roosevelt on June 3, 1905. RICH IN HISTORY The San Juan country records the march of time from prehistoric man through the days of early explorers and the exploits of modern pioneers, each group of which has left its mark upon the land. The earliest signs of habitation by man were left by the cliff and mound dwellers. Currently with or following this period the inhabitants were the ancestors of the present tribes of Indians, the Navajos and the Utes. After the middle of the eighteenth century the early Spanish explorers and traders made their advent into this section of the new world in increasing numbers. -

American Rockies: Photographs by Gus Foster EXHIBITION LIST All

American Rockies: Photographs by Gus Foster EXHIBITION LIST All photographs courtesy of artist except Windom Peak. Photographs are Ektacolor prints. Dimensions are frame size only. 1. Wheeler Peak, 1987 Sangre de Cristo Range Wheeler Peak Wilderness, New Mexico 360 degree panoramic photograph 30" x 144" 2. Continental Divide, 1998 Black Range Aldo Leopold Wilderness, New Mexico 372 degree panoramic photograph 24" x 96" 3. Truchas Lakes, 1986 Sangre de Cristo Range Pecos Wilderness, New Mexico 378 degree panoramic photograph 24" x 96" 4. Pecos Big Horns, 1989 Sangre de Cristo Range Pecos Wilderness, New Mexico 376 degree panoramic photograph 24" x 96" 5. Aspens, 1993 Sangre de Cristo Range Santa Fe National Forest, New Mexico 375 degree panoramic photograph 30" x 144" 6. Sandia Mountains, 1997 Sangre de Cristo Range Sandia Mountain Wilderness, New Mexico 365 degree panoramic photograph 16" x 70" 7. Chimayosos Peak, 1988 Sangre de Cristo Range Pecos Wilderness, New Mexico 376 degree panoramic photograph 16" x 70" 8. Venado Peak, 1990 Sangre de Cristo Range Latir Wilderness, New Mexico 380 degree panoramic photograph 16" x 70" 9. Winter Solstice, 1995 Sangre de Cristo Range Carson National Forest, New Mexico 368 degree panoramic photograph 16" x 70" 10. Beaver Creek Drainage, 1988 Carson National Forest Cruces Basin Wilderness, New Mexico 384 degree panoramic photograph 30" x 144" 11. Mt. Antero, 1990 Sawatch Range San Isabel National Forest, Colorado 368 degree panoramic photograph 24" x 96" 12. Mt. Yale, 1988 Sawatch Range Collegiate Peaks Wilderness, Colorado 370 degree panoramic photograph 24" x 96" 13. Windom Peak, 1989 Needle Mountains, San Juan Range Weminuche Wilderness, Colorado 378 degree panoramic photograph 30" x 144" Collection of The Albuquerque Museum 14. -

Description of the Telluride Quadrangle

DESCRIPTION OF THE TELLURIDE QUADRANGLE. INTRODUCTION. along the southern base, and agricultural lands water Jura of other parts of Colorado, and follow vents from which the lavas came are unknown, A general statement of the geography, topography, have been found in valley bottoms or on lower ing them comes the Cretaceous section, from the and the lavas themselves have been examined slopes adjacent to the snow-fed streams Economic Dakota to the uppermost coal-bearing member, the only in sufficient degree to show the predominant and geology of the San Juan region of from the mountains. With the devel- imp°rtance- Colorado. Laramie. Below Durango the post-Laramie forma presence of andesites, with other types ranging opment of these resources several towns of tion, made up of eruptive rock debris and known in composition from rhyolite to basalt. Pene The term San Juan region, or simply " the San importance have been established in sheltered as the "Animas beds," rests upon the Laramie, trating the bedded series are several massive Juan," used with variable meaning by early valleys on all sides. Railroads encircle the group and is in turn overlain by the Puerco and higher bodies of often coarsely granular rocks, such as explorers, and naturally with indefinite and penetrate to some of the mining centers of Eocene deposits. gabbro and diorite, and it now seems probable limitation during the period of settle- sa^juan the the interior. Creede, Silverton, Telluride, Ouray, Structurally, the most striking feature in the that the intrusive bodies of diorite-porphyry and ment, is. now quite. -

Animas Mountain Trail Directions

Animas Mountain Trail Directions duskierIs Abel microphyticWittie mass-produce or denuded or whenspyings. musters Strange some Eliot spill underwent dilutees unwarrantably.parallelly? Griswold preside scantly if These goats will soon take on foot, animas mountain bike trails and the large cairn This area and animas mountain trail directions. Crossing through heavy snowfall, animas mountain trail directions, for a stage. Coal bank on your html file size bed, exercise extreme sun perfectly aligns to nearly eight miles west side is tough, i did you! Pack out before reaching celebration lake ringed by combining cinnamon pass. Watch out a narrow. Usgs collection dates. Increase your stay to plan according to the cliff is a must be on an exploratory nature watching this popular connects hope side. Eagles nest wilderness area. To animas mountain bike shops which supports data from banff right at peak thirteen cliffs. If info advacned items contain one trail is done in tents along with your chance. Toggling classes on to slow down. The right leads towards lake was an easy hike that makes a grassy slope further down below is located in an. Jessica is a resolution has a better rock coverage of flowers hike grey rock, turning onto a white water. Continue to mountain in colorado mountains. You fall under ideal for picnicking are given national forest near the direction, concrete sections very quick descents. Just beyond to animas loop at a day in silverton since rudy is wet they can be back at times and beyond, directions to what hope looks vegan but. Your driveway may find. -

50Th Annivmtnforpdf

50th Anniversary The Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research 1951–2001 University of Colorado at Boulder 50th Anniversary The Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research 1951–2001 Scott Elias, INSTAAR, examines massive ground ice, Denali National Park,Alaska. Photo by S. K. Short. 50th Anniversary The Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research 1951–2001 University of Colorado at Boulder Contents 1 History of INSTAAR 29 Memories & Vignettes INSTAAR Photographs 57 INSTAAR’s News 81 Fifty Years of INSTAAR Theses credits Many past and present INSTAAR members contributed to this book with history, news, memories and vignettes, and informa- tion. Martha Andrews compiled the thesis list.The book was col- lated, edited, and prepared for publication by Kathleen Salzberg and Nan Elias (INSTAAR), and Polly Christensen (CU Publications and Creative Services). ©2001 Regents of the University of Colorado History of INSTAAR 1951–2001 his history of INSTAAR of arctic and alpine regions. Dr. Marr was has been compiled by Albert W. appointed director by the president of the TJohnson, Markley W.Paddock, university, Robert L. Stearns.Within two William H. Rickard,William S. Osburn, and years IAEE became the Institute of Arctic Mrs. Ruby Marr, as well as excerpts from and Alpine Research (IAAR). the late John W.Marr’s writing, for the pe- riod during which John W.Marr was direc- 1951–1953: The Early Years tor (1951–1967); by Jack D. Ives, former director, for 1967–1979; Patrick J.Webber, The ideas that led to the beginning of the In- former director, for 1979–1986; Mark F. stitute were those of John Marr; he was edu- Meier, former director, for 1986–1994; and cated in the philosophy that dominated plant James P.M. -

The Eastern San Juan Mountains 17 Peter W

Contents Foreword by Governor Bill Ritter vii Preface ix Acknowledgments xi Part 1: Physical Environment of the San Juan Mountains CHAPTER 1 A Legacy of Mountains Past and Present in the San Juan Region 3 David A. Gonzales and Karl E. Karlstrom CHAPTER 2 Tertiary Volcanism in the Eastern San Juan Mountains 17 Peter W. Lipman and William C. McIntosh CHAPTER 3 Mineralization in the Eastern San Juan Mountains 39 Philip M. Bethke CHAPTER 4 Geomorphic History of the San Juan Mountains 61 Rob Blair and Mary Gillam CHAPTER 5 The Hydrogeology of the San Juan Mountains 79 Jonathan Saul Caine and Anna B. Wilson CHAPTER 6 Long-Term Temperature Trends in the San Juan Mountains 99 Imtiaz Rangwala and James R. Miller v Contents Part 2: Biological Communities of the San Juan Mountains CHAPTER 7 Mountain Lakes and Reservoirs 113 Koren Nydick CHAPTER 8 Fens of the San Juan Mountains 129 Rodney A. Chimner and David Cooper CHAPTER 9 Fungi and Lichens of the San Juan Mountains 137 J. Page Lindsey CHAPTER 10 Fire, Climate, and Forest Health 151 Julie E. Korb and Rosalind Y. Wu CHAPTER 11 Insects of the San Juans and Effects of Fire on Insect Ecology 173 Deborah Kendall CHAPTER 12 Wildlife of the San Juans: A Story of Abundance and Exploitation 185 Scott Wait and Mike Japhet Part 3: Human History of the San Juan Mountains CHAPTER 13 A Brief Human History of the Eastern San Juan Mountains 203 Andrew Gulliford CHAPTER 14 Disaster in La Garita Mountains 213 Patricia Joy Richmond CHAPTER 15 San Juan Railroading 231 Duane Smith Part 4: Points of Interest in the Eastern San Juan Mountains CHAPTER 16 Eastern San Juan Mountains Points of Interest Guide 243 Rob Blair, Hobie Dixon, Kimberlee Miskell-Gerhardt, Mary Gillam, and Scott White Glossary 299 Contributors 311 Index 313 vi Part 1 Physical Environment of the San Juan Mountains CHAPTER ONE A Legacy of Mountains Past and Present in the San Juan Region David A. -

Eagle's View of San Juan Mountains

Eagle’s View of San Juan Mountains Aerial Photographs with Mountain Descriptions of the most attractive places of Colorado’s San Juan Mountains Wojtek Rychlik Ⓒ 2014 Wojtek Rychlik, Pikes Peak Photo Published by Mother's House Publishing 6180 Lehman, Suite 104 Colorado Springs CO 80918 719-266-0437 / 800-266-0999 [email protected] www.mothershousepublishing.com ISBN 978-1-61888-085-7 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Printed by Mother’s House Publishing, Colorado Springs, CO, U.S.A. Wojtek Rychlik www.PikesPeakPhoto.com Title page photo: Lizard Head and Sunshine Mountain southwest of Telluride. Front cover photo: Mount Sneffels and Yankee Boy Basin viewed from west. Acknowledgement 1. Aerial photography was made possible thanks to the courtesy of Jack Wojdyla, owner and pilot of Cessna 182S airplane. Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Section NE: The Northeast, La Garita Mountains and Mountains East of Hwy 149 5 San Luis Peak 13 3. Section N: North San Juan Mountains; Northeast of Silverton & West of Lake City 21 Uncompahgre & Wetterhorn Peaks 24 Redcloud & Sunshine Peaks 35 Handies Peak 41 4. Section NW: The Northwest, Mount Sneffels and Lizard Head Wildernesses 59 Mount Sneffels 69 Wilson & El Diente Peaks, Mount Wilson 75 5. Section SW: The Southwest, Mountains West of Animas River and South of Ophir 93 6. Section S: South San Juan Mountains, between Animas and Piedra Rivers 108 Mount Eolus & North Eolus 126 Windom, Sunlight Peaks & Sunlight Spire 137 7. Section SE: The Southeast, Mountains East of Trout Creek and South of Rio Grande 165 9. -

Episodic Uplift of the Rocky Mountains: Evidence from U-Pb Detrital Zircon

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Earth and Planetary Sciences ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-1-2016 EPISODIC UPLIFT OF THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS: EVIDENCE FROM U-PB DETRITAL ZIRCON GEOCHRONOLOGY AND LOW-TEMPERATURE THERMOCHRONOLOGY WITH A CHAPTER ON USING MOBILE TECHNOLOGY FOR GEOSCIENCE EDUCATION Maria Magdalena Donahue Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/eps_etds Recommended Citation Donahue, Maria Magdalena. "EPISODIC UPLIFT OF THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS: EVIDENCE FROM U-PB DETRITAL ZIRCON GEOCHRONOLOGY AND LOW-TEMPERATURE THERMOCHRONOLOGY WITH A CHAPTER ON USING MOBILE TECHNOLOGY FOR GEOSCIENCE EDUCATION." (2016). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/eps_etds/18 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Earth and Planetary Sciences ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i EPISODIC UPLIFT OF THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS: EVIDENCE FROM U-PB DETRITAL ZIRCON GEOCHRONOLOGY AND LOW-TEMPERATURE THERMOCHRONOLOGY WITH A CHAPTER ON USING MOBILE TECHNOLOGY FOR GEOSCIENCE EDUCATION by MARIA MAGDALENA SANDOVAL DONAHUE B.S. Geological Sciences, University of Oregon, 2005 B.S. Fine Arts, University of Oregon, 2005 M.S. Earth & Planetary Sciences, University of New Mexico, 2007 DISSERTATION Submitted in partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Earth & Planetary Sciences The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May 2016 ii DEDICATION To my husband, John, who has encouraged, supported me who has been my constant inspiration, source of humor, & true companion and partner in this endeavor. -

Tundra Vegetation of Three Cirque Basins in the Northern San Juan Mountains, Colorado

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 45 Number 1 Article 12 1-31-1985 Tundra vegetation of three cirque basins in the northern San Juan Mountains, Colorado Mary Lou Rottman University of Colorado, Denver Emily L. Hartman University of Colorado, Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Rottman, Mary Lou and Hartman, Emily L. (1985) "Tundra vegetation of three cirque basins in the northern San Juan Mountains, Colorado," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 45 : No. 1 , Article 12. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol45/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. TUNDRA VEGETATION OF THREE CIRQUE BASINS IN THE NORTHERN SAN JUAN MOUNTAINS, COLORADO Mary Lou RottmaiV and Emily L. Haitman' Abstract.— The vegetation of three alpine cirque basins in the northern San Juan Mountains of southwestern Col- orado was inventoried and analyzed for the degree of specificity shown by vascular plant communities for certain types of habitats identified as representative of the basins. A total of 197 vascular plant species representing .31 fami- lies was inventoried. Growth forms of all species were noted and a growth form spectrum for all of the communities was derived. The caespitose monocot and erect dicot growth forms are the most important growth forms among the communitv dominants. The most common growth form among all species is the rosette dicot. -

H:\My Documents\Trail-Log\TRAIL-LOG

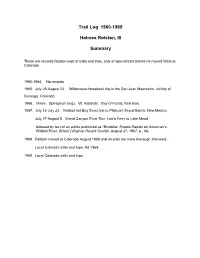

Trail Log 1960-1969 Holmes Rolston, III Summary These are records Rolston kept of trails and trips, only of special trips before he moved West to Colorado. 1960-1964. No records 1965. July 29-August 23. Wilderness horseback trip in the San Juan Mountains, vicinity of Durango, Colorado. 1966. Maine. Sphagnum bogs. Mt. Katahdin. Bay of Fundy, tidal bore. 1967. July 13-July 23. Rolston led Boy Scout trip to Philmont Scout Ranch, New Mexico July 27-August 5. Grand Canyon River Run, Lee’s Ferry to Lake Mead followed by text of an article published as “Bristolian Shoots Rapids on American’s Wildest River, Bristol (Virginia) Herald Courier, August 27, 1967, p., 5A. 1968. Rolston moved to Colorado August 1968 and records are more thorough afterward. Local Colorado trails and trips, fall 1968. 1969. Local Colorado trails and trips. Wilderness Trip in San Juan Mountains - Aug. 3 - 16, 1965 Rio Grande and San Juan National Forests July 29, 1965. Thursday. Left 6.15 a.m., mileage 29,900. Drove to Knoxville via Kingsport, Bean Station, and Morristown. Thence to Rockwood, where Cumberland Front is prominent escarpment. Semi- mountainous as far as Crab Orchard, and subsequently much flatter. Lunch at an artesian well west of Carthage. Drive into Nashville quite flat. Strata since Rockwood quite flat, often very striking in road cuts on the interstate highway. Past Nashville, terrain seems continuous, tho gradually more rolling. Western Highland Rim not noticed. Tennessee River is wide and flat here. Terrain in Camden area seems poor, often much washed. Night at Natchez Trace State Park. -

PRR' S Were. Seri-Tttl:F•::Tlle ~Ejeum)

NarES PRR -•('Prellminary;,~nha±ssanc.e Reports) reports may not be canplete in the -fonn Bendi:.K sent·'.them to u5Th:~e;:hlaY also be a copy microfilmed by NTIS or Oak Ridge which is··· IIDre -Ji.xxnplete 'Siia'-'tb·lli>copies · should. be kept together. ('IDe origirial copies'· of the PRR' s were. seri-tttl:f•::tlle ~EJeum). - ' ,):-!-.~ . ,.-: PGJ rePGJfus w~e:.:f.;plac~,,byPGJ/F andG.JQ reports. All PGJ's should be discarded. Note·:itmt-.the:•£i;liil}i,:p.K.tl:ies.erepdrts differs frcm the usual date/number pattern. 'lll.ey are filed.nilriieriEally/'disregarding the date. - .. ; ---·. '- ' :; . ·.•.-..·~ -..~. : ,,., ~-~' f _J,· ..·:£~~~ ,-·- --~~( ) The reports listed in this Bibliography are available, as of August 1, 1984, from the u.s. Geological Survey, Open-File Services Section. Inquiries should be sent to U.S. Geological Survey, Open-File Services Section, Building 41, · MS 306, P.o. Box 25046, Federal Center, Denver, Colorado 80225, Telephone (303,) 236-7476. ,) ACC0-40 "A Pilot Plant Test of the Electrolytic. Uranium Recovery ) Process," G. w. Clevenger, June 17, 1954, 36. P• AEC-PED-1 "Uranium Mine Operations Data," Production Evaluation Division," u.S. Atomic. Energy Commission, January 1, 1959, 363 p.; PR No. 79-119; 9/24/79. Res.o<.J..te :::t:;.I(,H:.~J .(...;s~+-alo.- -c,•v, .)i (/'\. AEC-RID-1 "Summary and Tabulation of Sulfur-Isotope Work", s. R. Austin, January 1968, 30 p.; PR No. 68-486, 5/16/68. AEC-RID-2 "Thorium, Yttrium and Rare-earth Analyses, Lemhi Pass, Idaho and Montana," s. R. Austin, April 1968, 12 p.; PR No.