Artists in Thought from Classical Reception to Criticism As a Creative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

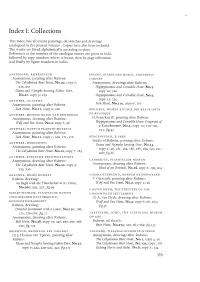

Index I: Collections

Index I: Collections This index lists ail extant paintings, oil sketches and drawings catalogued in the present volume . Copies have also been included. The works are listed alphabetically according to place. References to the number of the catalogue entries are given in bold, followed by copy numbers where relevant, then by page references and finally by figure numbers in italics. AMSTERDAM, RIJKSMUSEUM BRUGES, STEDEEÏJKE MUSEA, STEINMETZ- Anonymous, painting after Rubens : CABINET The Calydonian Boar Hunt, N o .20, copy 6; Anonymous, drawings after Rubens: 235, 237 Hippopotamus and Crocodile Hunt, N o .5, Diana and Nymphs hanting Fallow Deer, copy 12; 120 N o.21, copy 5; 239 Hippopotamus and Crocodile Hunt, N o .5, cop y 13; 120 ANTWERP, ACADEMY Anonymous, painting after Rubens: Lion Hunt, N o.ne, copy 6; 177 Lion Hunt, N o.11, copy 2; 162 BRUSSELS, MUSÉES ROYAUX DES BEAUX-ARTS DE BELGIQUE ANTWERP, MUSEUM MAYER VAN DEN BERGH Anonymous, drawing after Rubens: H.Francken II, painting after Rubens: Hippopotamus and Crocodile Hunt: Fragment of W olf and Fox Hunt, N o .2, copy 7; 96 a Kunstkammer, N o.5, copy 10; 119-120, ANTW ERP, MUSEUM PLANTIN-M O RETUS 123 ;fig .4S Anonymous, painting after Rubens: Lion Hunt, N o .n , copy 1; 162, 171, 178 BÜRGENSTOCK, F. FREY Studio of Rubens, painting after Rubens: ANTWERP, RUBENSHUIS Diana and Nymphs hunting Deer, N o .13, Anonymous, painting after Rubens : copy 2; 46, 181, 182, 186, 188, 189, 190, 191, The Calydonian Boar Hunt, N o .12, copy 7; 185 208; fig.S6 ANTWERP, STEDELIJK PRENTENKABINET Anonymous, -

The Great Apostasy

The Great Apostasy R. J. M. I. By The Precious Blood of Jesus Christ; The Grace of the God of the Holy Catholic Church; The Mediation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Our Lady of Good Counsel and Crusher of Heretics; The Protection of Saint Joseph, Patriarch of the Holy Family and Patron of the Holy Catholic Church; The Guidance of the Good Saint Anne, Mother of Mary and Grandmother of God; The Intercession of the Archangels Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael; The Intercession of All the Other Angels and Saints; and the Cooperation of Richard Joseph Michael Ibranyi To Jesus through Mary Júdica me, Deus, et discérne causam meam de gente non sancta: ab hómine iníquo, et dolóso érue me Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam 2 “I saw under the sun in the place of judgment wickedness, and in the place of justice iniquity.” (Ecclesiastes 3:16) “Woe to you, apostate children, saith the Lord, that you would take counsel, and not of me: and would begin a web, and not by my spirit, that you might add sin upon sin… Cry, cease not, lift up thy voice like a trumpet, and shew my people their wicked doings and the house of Jacob their sins… How is the faithful city, that was full of judgment, become a harlot?” (Isaias 30:1; 58:1; 1:21) “Therefore thus saith the Lord: Ask among the nations: Who hath heard such horrible things, as the virgin of Israel hath done to excess? My people have forgotten me, sacrificing in vain and stumbling in their way in ancient paths.” (Jeremias 18:13, 15) “And the word of the Lord came to me, saying: Son of man, say to her: Thou art a land that is unclean, and not rained upon in the day of wrath. -

Review of the Year 2012–2013

review of the year TH E April 2012 – March 2013 NATIONAL GALLEY TH E NATIONAL GALLEY review of the year April 2012 – March 2013 published by order of the trustees of the national gallery london 2013 Contents Introduction 5 Director’s Foreword 6 Acquisitions 10 Loans 30 Conservation 36 Framing 40 Exhibitions 56 Education 57 Scientific Research 62 Research and Publications 66 Private Support of the Gallery 70 Trustees and Committees of the National Gallery Board 74 Financial Information 74 National Gallery Company Ltd 76 Fur in Renaissance Paintings 78 For a full list of loans, staff publications and external commitments between April 2012 and March 2013, see www.nationalgallery.org.uk/about-us/organisation/ annual-review the national gallery review of the year 2012– 2013 introduction The acquisitions made by the National Gallery Lucian Freud in the last years of his life expressed during this year have been outstanding in quality the hope that his great painting by Corot would and so numerous that this Review, which provides hang here, as a way of thanking Britain for the a record of each one, is of unusual length. Most refuge it provided for his family when it fled from come from the collection of Sir Denis Mahon to Vienna in the 1930s. We are grateful to the Secretary whom tribute was paid in last year’s Review, and of State for ensuring that it is indeed now on display have been on loan for many years and thus have in the National Gallery and also for her support for very long been thought of as part of the National the introduction in 2012 of a new Cultural Gifts Gallery Collection – Sir Denis himself always Scheme, which will encourage lifetime gifts of thought of them in this way. -

Lecture on TITIAN 2020

Tuesday 3 March 2020 at 6.30 for 7 pm THE TRIUMPH OF PAINTING: TITIAN IN THE SERVICE OF PHILIP II a Lecture by PROF. CHARLES HOPE Accademia Italiana/Artstur at Ognisko, 55 Exhibition Road, SW7 2PN “Titian’s most loyal and effective patron was Philip II, for whom he worked for more than a quarter of a century, producing masterpieces such as the mythologies on display in the National Gallery. The pictures which he painted for the King changed the course of European painting.” - Charles Hope Following the recent announcement from the National Gallery of Art of their new exhibition TITIAN: LOVE DESIRE DEATH opening on Friday 13 March 2020 on Titian’s late Works, among which there will be the famous poesie painted by Titian in his later years for his Patron Philip II of Spain, we have arranged this lecture. Titian. Diana and Actaeon In the exhibition there will be three of the Poesie, belonging to the National Gallery: Diana and Actaeon, Diana and Callisto and the Death of Actaeon together with other paintings coming from all over the world. (All three illustrated here and in our website www.artstur.com) For this lecture we will have the honour of having Prof Charles Hope, former director of The WARBURG INSTITUTE. He is a specialist on the art of the Italian Renaissance, on which he has published extensively, including studies on Alberti, Mantegna, Giorgione, Vasari and especially Titian. He has been involved in the organisation of many exhibitions including The Genius of Venice 1500-1600 (Royal Academy, 1983) To book contact Accademia Italiana / Artstur Titian. -

Non-Finito I Tjelesnost Slika: Početci I Odlike (Protu)Mimetičkog Pristupa

Non-finito i tjelesnost slika: početci i odlike (protu)mimetičkog pristupa Zmijarević, Nikola Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2021 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zadar / Sveučilište u Zadru Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:162:156644 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-28 Repository / Repozitorij: University of Zadar Institutional Repository of evaluation works Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za povijest umjetnosti Diplomski sveučilišni studij povijesti umjetnosti; smjer: konzervatorski i muzejsko-galerijski (jednopredmetni) Nikola Zmijarević Non-finito i tjelesnost slika: početci i odlike (protu)mimetičkog pristupa Diplomski rad Zadar, 2021. Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za povijest umjetnosti Diplomski sveučilišni studij povijesti umjetnosti; smjer: konzervatorski i muzejsko-galerijski (jednopredmetni) Non-finito i tjelesnost slika: početci i odlike (protu)mimetičkog pristupa Diplomski rad Student/ica: Mentor/ica: Nikola Zmijarević izv. prof. dr. sc. Laris Borić Zadar, 2021. Izjava o akademskoj čestitosti Ja, Nikola Zmijarević, ovime izjavljujem da je moj diplomski rad pod naslovom Non- finito i tjelesnost slika: početci i odlike (protu)mimetičkog pristupa rezultat mojega vlastitog rada, da se temelji na mojim istraživanjima te da se oslanja na izvore i radove navedene u bilješkama i popisu literature. Ni jedan dio mojega rada nije napisan na nedopušten način, odnosno nije prepisan iz necitiranih radova i ne krši bilo čija autorska prava. Izjavljujem da ni jedan dio ovoga rada nije iskorišten u kojem drugom radu pri bilo kojoj drugoj visokoškolskoj, znanstvenoj, obrazovnoj ili inoj ustanovi. Sadržaj mojega rada u potpunosti odgovara sadržaju obranjenoga i nakon obrane uređenoga rada. Zadar, 5. -

Autumn 2012 Catalogue:1 20/4/12 10:28 Page 1

Autumn 12 Cat. Cover multiple bags:1 16/4/12 12:19 Page 1 YaleBooks www.yalebooks.co.uk twitter.com/yalebooks yalebooks.wordpress.com Yale facebook.com/yalebooks autumn & winter 2012 Yale autumn & winter 2012 Autumn 2012 Cat. Inside Cover:1 20/4/12 10:23 Page 1 Yale sales representatives and overseas agents Great Britain Central Europe China, Hong Kong Scotland and the North Ewa Ledóchowicz & The Philippines Peter Hodgkiss PO Box 8 Ed Summerson 16 The Gardens 05-520 Konstancin-Jeziorna Asia Publishers Services Ltd Whitley Bay NE25 8BG Poland Units B & D Tel. 0191 281 7838 Tel. (+48) 22 754 17 64 17/F Gee Chang Hong Centre Mobile ’phone 07803 012 461 Fax. (+48) 22 756 45 72 65 Wong Chuk Hang Road e-mail: [email protected] Mobile ’phone (+48) 606 488 122 Aberdeen e-mail: [email protected] Hong Kong North West England, inc. Staffordshire Tel. (+852) 2553 9289/9280 Sally Sharp Australia, New Zealand, Fax. (+852) 2554 2912 53 Southway Fiji & Papua New Guinea e-mail: [email protected] Eldwick, Bingley Inbooks West Yorkshire BD16 3DT Locked Bag 535 Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, Tel. 01274 511 536 Frenchs Forest Cambodia, Indonesia & Brunei Mobile ’phone 07803 008 218 NSW 2086 APD Singapore Ptd Ltd e-mail: [email protected] Australia 52 Genting Lane #06-05 Tel: (+61) 2 8988 5082 Ruby Land Complex 1 South Wales, South and South West Fax: (+61) 2 8988 5090 Singapore 349560 England, inc. South London e-mail: [email protected] Tel. (+65) 6749 3551 Josh Houston Fax. -

Profiling Women in Sixteenth-Century Italian

BEAUTY, POWER, PROPAGANDA, AND CELEBRATION: PROFILING WOMEN IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY ITALIAN COMMEMORATIVE MEDALS by CHRISTINE CHIORIAN WOLKEN Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Edward Olszewski Department of Art History CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERISTY August, 2012 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Christine Chiorian Wolken _______________________________________________________ Doctor of Philosophy Candidate for the __________________________________________ degree*. Edward J. Olszewski (signed) _________________________________________________________ (Chair of the Committee) Catherine Scallen __________________________________________________________________ Jon Seydl __________________________________________________________________ Holly Witchey __________________________________________________________________ April 2, 2012 (date)_______________________ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. 1 To my children, Sofia, Juliet, and Edward 2 Table of Contents List of Images ……………………………………………………………………..….4 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………...…..12 Abstract……………………………………………………………………………...15 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………16 Chapter 1: Situating Sixteenth-Century Medals of Women: the history, production techniques and stylistic developments in the medal………...44 Chapter 2: Expressing the Link between Beauty and -

Annual Review 2013–2014 the National Galleries of Scotland Cares For, Develops, Researches and Displays the National Collection of Scottish

Annual Review 2013–2014 The National Galleries of Scotland cares for, develops, researches and displays the national collection of Scottish © Keith Hunter Photography © Andrew Lee © Keith Hunter Photography and international fine art and, Scottish National Gallery Scottish National Portrait Gallery Scottish National Gallery with a lively and innovative The Scottish National Gallery comprises The Scottish National Portrait Gallery of Modern Art One three linked buildings at the foot of is about the people of Scotland – past Home to Scotland’s outstanding national programme of exhibitions, the Mound in Edinburgh. The Gallery and present, famous or forgotten. The collection of modern and contemporary education and publications, houses the national collection of fine portraits are windows into their lives art, the Scottish National Gallery of art from the early Renaissance to the and the displays throughout the beautiful Modern Art comprises two buildings, aims to engage, inform end of the nineteenth century, including Arts and Crafts building help explain Modern One and Modern Two. The early the national collection of Scottish art how the men and women of earlier times part of the collection features French and inspire the broadest from around 1600 to 1900. The Gallery made Scotland the country it is today. and Russian art from the beginning of possible public. is joined to the Royal Scottish Academy Photography and film also form part of the twentieth century, cubist paintings building via the underground Weston the collection and help to make Scotland’s and superb holdings of Expressionist and Link, which contains a restaurant, café, colourful history come alive. modern British art. -

Opera & Ballet 2017

12mm spine THE MUSIC SALES GROUP A CATALOGUE OF WORKS FOR THE STAGE ALPHONSE LEDUC ASSOCIATED MUSIC PUBLISHERS BOSWORTH CHESTER MUSIC OPERA / MUSICSALES BALLET OPERA/BALLET EDITION WILHELM HANSEN NOVELLO & COMPANY G.SCHIRMER UNIÓN MUSICAL EDICIONES NEW CAT08195 PUBLISHED BY THE MUSIC SALES GROUP EDITION CAT08195 Opera/Ballet Cover.indd All Pages 13/04/2017 11:01 MUSICSALES CAT08195 Chester Opera-Ballet Brochure 2017.indd 1 1 12/04/2017 13:09 Hans Abrahamsen Mark Adamo John Adams John Luther Adams Louise Alenius Boserup George Antheil Craig Armstrong Malcolm Arnold Matthew Aucoin Samuel Barber Jeff Beal Iain Bell Richard Rodney Bennett Lennox Berkeley Arthur Bliss Ernest Bloch Anders Brødsgaard Peter Bruun Geoffrey Burgon Britta Byström Benet Casablancas Elliott Carter Daniel Catán Carlos Chávez Stewart Copeland John Corigliano Henry Cowell MUSICSALES Richard Danielpour Donnacha Dennehy Bryce Dessner Avner Dorman Søren Nils Eichberg Ludovico Einaudi Brian Elias Duke Ellington Manuel de Falla Gabriela Lena Frank Philip Glass Michael Gordon Henryk Mikolaj Górecki Morton Gould José Luis Greco Jorge Grundman Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen Albert Guinovart Haflidi Hallgrímsson John Harbison Henrik Hellstenius Hans Werner Henze Juliana Hodkinson Bo Holten Arthur Honegger Karel Husa Jacques Ibert Angel Illarramendi Aaron Jay Kernis CAT08195 Chester Opera-Ballet Brochure 2017.indd 2 12/04/2017 13:09 2 Leon Kirchner Anders Koppel Ezra Laderman David Lang Rued Langgaard Peter Lieberson Bent Lorentzen Witold Lutosławski Missy Mazzoli Niels Marthinsen Peter Maxwell Davies John McCabe Gian Carlo Menotti Olivier Messiaen Darius Milhaud Nico Muhly Thea Musgrave Carl Nielsen Arne Nordheim Per Nørgård Michael Nyman Tarik O’Regan Andy Pape Ramon Paus Anthony Payne Jocelyn Pook Francis Poulenc OPERA/BALLET André Previn Karl Aage Rasmussen Sunleif Rasmussen Robin Rimbaud (Scanner) Robert X. -

Metamorphoses: `The Transformation and Transmutation of the Arcadian Dream'

Durham E-Theses Pastoral elements and imagery in Ovid's metamorphoses: `the transformation and transmutation of the Arcadian dream' Dibble, Alison Jane How to cite: Dibble, Alison Jane (2002) Pastoral elements and imagery in Ovid's metamorphoses: `the transformation and transmutation of the Arcadian dream', Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3836/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS AND ANCIENT HISTORY 2002 M.A. by Research PASTORAL ELEMENTS AND IMAGERY IN OVID'S METAMORPHOSES: 'THE TRANSFORMATION AND TRANSMUTATION OF THE ARCADIAN DREAM' ALISON JANE DIBBLE PASTORALELEMENTSANDIMAGERYIN OVID'S METAMORPHOSES: 'THE TRANSFORMATION AND TRANSMUTATION OF THE ARCADIAN DREAM.' ALISON J. DIBBLE 'They, looking back, all the eastern side beheld Of Paradise, so late their happy seat, Waved over by that flaming brand, the gate With dreadful faces thronged and fiery arms: Some natural tears they dropped, but wiped them soon; The world was all before them, where to choose Their place of rest, and Providence their guide; They, hand in hand, with wandering steps and slow, Through Eden took their solitary way. -

Titian Titian (C.488/1490 – 1576) Is Considered the Most Important Member of the 16Th-Century Venetian School. He Was One of T

Titian Titian (c.488/1490 – 1576) is considered the most important member of the 16th-century Venetian school. He was one of the most versatile of Italian painters, equally adept with portraits, landscape backgrounds, and mythological and religious subjects. His painting methods, particularly in the application and use of colour, would exercise a profound influence not only on painters of the Italian Renaissance, but on future generations of Western art. During the course of his long life, Titian's artistic manner changed drastically but he retained a lifelong interest in colour. Although his mature works may not contain the vivid, luminous tints of his early pieces, their loose brushwork and subtlety of tone are without precedent in the history of Western painting. 01 Self-Portrait c1567 Dating to about 1560, when Titian was at least 70 years old, this is the latter of two surviving self-portraits by the artist. The work is a realistic and unflattering depiction of the physical effects of old age, and as such shows none of the self-confidence of his earlier self-portrait. He looks remote and gaunt, staring into the middle distance, seemingly lost in thought. Still, this portrait projects dignity, authority and the mark of a master painter to a greater extent than the earlier surviving self-portrait. The artist is dressed in simple but expensive clothes. In the lower left corner of the canvas he holds a paintbrush. Although the presence of the paintbrush is understated, it is the element that gives legitimacy to his implied status. This is one of the earliest self-portraits in western art in which the artist reveals himself as a painter. -

'A Boy with a Bird' in the National Gallery: Two Responses to a Titian

02 TB 28 pp001-096 5 low res_REV_TB 27 Prelims.qxd 11/03/2011 14:25 Page 1 NATIONAL GALLERY TECHNICAL BULLETIN VOLUME 28, 2007 National Gallery Company Limited Distributed by Yale University Press 02 TB 28 pp001-096 5 low res_REV_TB 27 Prelims.qxd 11/03/2011 14:25 Page 2 This volume of the Technical Bulletin has been funded by the American Friends of the National Gallery, London with a generous donation from Mrs Charles Wrightsman. Series editor Ashok Roy © National Gallery Company Limited 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. First published in Great Britain in 2007 by National Gallery Company Limited St Vincent House, 30 Orange Street London wc2h 7hh www.nationalgallery.co.uk British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this journal is available from the British Library isbn 978 1 85709 357 5 issn 0140 7430 525049 Publisher Kate Bell Project manager Jan Green Editor Diana Davies Designer Tim Harvey Picture research Suzanne Bosman Production Jane Hyne and Penny Le Tissier Repro by Alta Image, London Printed in Italy by Conti Tipocolor FRONT COVER Claude-Oscar Monet, Irises (NG 6383), detail of plate 2, page 59. TITLE PAGE Bernardo Daddi, Four Musical Angels, Oxford, Christ Church, detail of plate 2, page 5. Photographic credits PARIS All photographs reproduced in this Bulletin are Durand-Ruel © The National Gallery, London, unless credited © Archives Durand-Ruel: p.