Journal of Environment and Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Was Life Like in the Ancient Kingdom of Benin? Today’S Enquiry: Why Is It Important to Learn About Benin in School?

History Our main enquiry question this term: What was life like in the Ancient Kingdom of Benin? Today’s enquiry: Why is it important to learn about Benin in school? Benin Where is Benin? Benin is a region in Nigeria, West Africa. Benin was once a civilisation of cities and towns, powerful Kings and a large empire which traded over long distances. The Benin Empire 900-1897 Benin began in the 900s when the Edo people settled in the rainforests of West Africa. By the 1400s they had created a wealthy kingdom with a powerful ruler, known as the Oba. As their kingdom expanded they built walls and moats around Benin City which showed incredible town planning and architecture. What do you think of Benin City? Benin craftsmen were skilful in Bronze and Ivory and had strong religious beliefs. During this time, West Africa invented the smelting (heating and melting) of copper and zinc ores and the casting of Bronze. What do you think that this might mean? Why might this be important? What might this invention allowed them to do? This allowed them to produced beautiful works of art, particularly bronze sculptures, which they are famous for. Watch this video to learn more: https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/topics/zpvckqt/articles/z84fvcw 7 Benin was the center of trade. Europeans tried to trade with Benin in the 15 and 16 century, especially for spices like black pepper. When the Europeans arrived 8 Benin’s society was so advanced in what they produced compared with Britain at the time. -

The Perception of Edo People on International and Irregular Migration

THE PERCEPTION OF EDO PEOPLE ON INTERNATIONAL AND IRREGULAR MIGRATION BY EDO STATE TASK FORCE AGAINST HUMAN TRAFFICKING (ETAHT) Supported by DFID funded Market Development Programme in the Niger Delta being implemented by Development Alternatives Incorporated. Lead Consultant: Professor (Mrs) K. A. Eghafona Department Of Sociology And Anthropology University Of Benin Observatory Researcher: Dr. Lugard Ibhafidon Sadoh Department Of Sociology And Anthropology University Of Benin Observatory Quality Control Team Lead: Okereke Chigozie Data analyst ETAHT Foreword: Professor (Mrs) Yinka Omorogbe Chairperson ETAHT March 2019 i List of Abbreviations and Acronyms AHT Anti-human Trafficking CDC Community Development Committee EUROPOL European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation (formerly the European Police Office and Europol Drugs Unit) ETAHT Edo State Task Force Against Human Trafficking HT Human trafficking IOM International Organization for Migration LGA Local Government Area NAPTIP National Agency For Prohibition of Traffic In Persons & Other Related Matters NGO Non-Governmental Organization SEEDS (Edo) State Economic Empowerment and Development Strategy TIP Trafficking in Persons UN United Nations UNODC United Nations Office on Drug and Crime USA United States of America ii Acknowledgements This perception study was carried out by the Edo State Taskforce Against Human Trafficking (ETAHT) using the service of a consultant from the University of Benin Observatory within the framework of the project Counter Trafficking Initiative. We are particularly grateful to the chairperson of ETAHT and Attorney General of Edo State; Professor Mrs. Yinka Omorogbe for her support in actualizing this project. The effort of Mr. Chigozie Okereke and other staff of ETAHT who provided assistance towards the actualization of this task is immensely appreciated. -

Kingdom of Benin Is Not the Same As 10 Colonisation When Invaders Take Over Control of a Benin

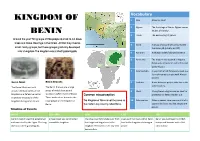

KINGDOM OF Vocabulary 1 Oba A king or chief. 2 Ogisos The first kings of Benin. Ogisos means BENIN ‘Rulers of the Sky’. 3 Trade The exchanging of goods. Around the year 900 groups of Edo people started to cut down trees and make clearings in the forest. At first they lived in 4 Guild A group of people who all complete small family groups, but these groups gradually developed the same job (usually a craft). into a kingdom. The kingdom was called Igodomigodo. 5 Animism A religion widely followed in Benin. 6 Benin city The modern city located in Nigeria. Previously, it has been called Edo and Igodomigodo. 7 Cowrie shells A sea shell which Europeans used as a form of money to trade with African leaders. Benin Moat Benin Bronzes 8 Civil war A war between people who live in the same country. The Benin Moat was built The Benin Bronzes are a large around the boundaries of the group of metal plaques and 9 Moat A long trench dug around an area for kingdom as a defensive barrier sculptures (often made of brass). Common misconception protection to keep invaders out. to protect the people of the These works of art decorate the kingdom during times of war. royal palace of the Kingdom of The Kingdom of Benin is not the same as 10 Colonisation When invaders take over control of a Benin. the modern day country called Benin. country by force, and live among the people. Timeline of Events 900 AD 900—1460 1180 1700 1897 Benin Kingdom was first established A huge moat was constructed The Oba royal family take over from A series of civil wars within Benin Benin was destroyed by British and was ruled by the Ogiso. -

Folktale Tradition of the Esan People and African Oral Literature

“OKHA”: FOLKTALE TRADITION OF THE ESAN PEOPLE AND AFRICAN ORAL LITERATURE 1ST IN THE SERIES OF INAUGURAL LECTURES OF SAMUEL ADEGBOYEGA UNIVERSITY OGWA, EDO STATE, NIGERIA. BY PROFESSOR BRIDGET O. INEGBEBOH B.A. M.A. PH.D (ENGLISH AND LITERATURE) (BENIN) M.ED. (ADMIN.) (BENIN), LLB. A.A.U (EKPOMA), BL. (ABUJA) LLM. (BENIN) Professor of English and Literature Department of Languages Samuel Adegboyega University, Ogwa. Wednesday, 11th Day of May, 2016. PROFESSOR BRIDGET O. INEGBEBOH B.A. M.A. PH.D (ENGLISH AND LITERATURE) (BENIN) M.ED. (ADMIN.) (BENIN), LLB. A.A.U (EKPOMA), BL. (ABUJA) LLM. (BENIN) 2 “OKHA”: FOLKTALE TRADITION OF THE ESAN PEOPLE AND AFRICAN ORAL LITERATURE 1ST IN THE SERIES OF INAUGURAL LECTURES OF SAMUEL ADEGBOYEGA UNIVERSITY OGWA, EDO STATE, NIGERIA. BY BRIDGET OBIAOZOR INEGBEBOH B.A. M.A. PH.D (ENGLISH AND LITERATURE) (BENIN) M.ED. (ADMIN.) (BENIN), LLB. A.A.U (EKPOMA), BL. (ABUJA) LLM. (BENIN) Professor of English and Literature Department of Languages Samuel Adegboyega University, Ogwa. Wednesday, 11th Day of May, 2016. 3 “OKHA”: FOLKTALE TRADITION OF THE ESAN PEOPLE AND AFRICAN ORAL LITERATURE Copyright 2016. Samuel Adegboyega University, Ogwa All Rights Reserved No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in any retrieval system or by any means, photocopying, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of Samuel Adegboyega University, Ogwa/Publishers. ISBN: Published in 2016 by: SAMUEL ADEGBOYEGA UNIVERSITY, OGWA, EDO STATE, NIGERIA. Printed by: 4 Vice-Chancellor, Chairman and members of the Governing Council of SAU, The Management of SAU, Distinguished Academia, My Lords Spiritual and Temporal, His Royal Majesties here present, All Chiefs present, Distinguished Guests, Representatives of the press and all Media Houses present, Staff and Students of Great SAU, Distinguished Ladies and Gentlemen. -

(Ekpo) Masquerade in Edo Belief: the Socio – Economic Relevance

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 19, Issue 1, Ver. VIII (Jan. 2014), PP 64-68 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org (Ekpo) Masquerade In Edo Belief: The Socio – Economic Relevance T. O. Ebhomienlen and M. O. Idemudia Abstract: This paper examines EKPO (masquerade) among the Edo and its socio-economic contributions to development. It sees EKPO Cult and its Festivals as a vehicle for social stability and cohesion. Masquerades features prominently in African traditional religions. It is not out of place to assert that the preponderance of masquerades in most African Socio- religious Cult is a reflection of their unitary mode of expressing that which they perceive and thought of the divine or out of the sphere of humans. The African recognizes the place of the ancestors and gives them appropriate veneration and reverence as they are seen as human representatives in the spirit world. This paper further seeks to reveal that masquerade is one of the ways the African use to convey the continuous participation of the ancestors in human affairs. Hence, the Yoruba and the Edo conceive of masquerades as visible symbolic representation of the ancestors. They consider them as sacred and special cult is accorded them. To both people, Masquerade is a bridge of the chasm between the living and the living dead. The literature also discusses that masquerade though a spiritual phenomenon is also a vehicle for Socio- economic development among the Edo people. The thrust of this paper is in this regards. A comparative and evaluative method is adopted in the crux of the discourse. -

BELIEF and RITUAL in the EDO TRADITIONAL RELIGION MICHAEL ROBERT WELTON B.A., University of British Columbia, 1964 a THESIS SUBM

BELIEF AND RITUAL IN THE EDO TRADITIONAL RELIGION by MICHAEL ROBERT WELTON B.A., University of British Columbia, 1964 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of ANTHROPOLOGY AND SOCIOLOGY We accept this thesis as conforming to the required staiydard^ THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, 1969 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and Study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thes,is for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada ABSTRACT The primary purpose of this study is to describe the Edo traditional religious system. Four assumptions undergird the general theoretical framework of the study. 1. That the divinities are personified beings capable of responding to ritual action as well as manifesting themselves in culture. 2. That the interaction between man and divinity will be patterned after such relationships and obligations that characterize social relations. 3. That interaction with divinity will be related to the attainment of goals at different levels of social structural reference. 4. That the divinity-to-group coordination will reflect the con• flicts and competition within the social structure. I have first of all sought to determine what the Edo beliefs about divinity are, i.e. -

African Civilisation from the Earliest Times to 1500 AD HDS101

COURSE MANUAL African Civilisation from the earliest Times to 1500 AD HDS101 University of Ibadan Distance Learning Centre Open and Distance Learning Course Series Development Copyright © 2016 by Distance Learning Centre, University of Ibadan, Ibadan. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN: 978-021 General Editor : Prof. Bayo Okunade University of Ibadan Distance Learning Centre University of Ibadan, Nigeria Telex: 31128NG Tel: +234 (80775935727) E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.dlc.ui.edu.ng Vice-Chancellor’s Message The Distance Learning Centre is building on a solid tradition of over two decades of service in the provision of External Studies Programme and now Distance Learning Education in Nigeria and beyond. The Distance Learning mode to which we are committed is providing access to many deserving Nigerians in having access to higher education especially those who by the nature of their engagement do not have the luxury of full time education. Recently, it is contributing in no small measure to providing places for teeming Nigerian youths who for one reason or the other could not get admission into the conventional universities. These course materials have been written by writers specially trained in ODL course delivery. The writers have made great efforts to provide up to date information, knowledge and skills in the different disciplines and ensure that the materials are user- friendly. In addition to provision of course materials in print and e-format, a lot of Information Technology input has also gone into the deployment of course materials. -

African Value System and the Impact of Westernization: a Critical Evaluation of Esan Society in Edo State, Nigeria

African Journal of History and Archaeology Vol. 3 No. 1 2018 ISSN 2579-048X www.iiardpub.org African Value System and the Impact of Westernization: A Critical Evaluation of Esan Society in Edo State, Nigeria Enato, Lucky Success Ehimeme Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma Department of History and International Studies, Edo state, Nigeria, P.M.B. 14 Abstract Africans from the pre-colonial era have their unique and distinct culture which is evidenced in their entire ways of life – socially, politically, religiously, economically and technologically. Their value systems as elements of their culture are depicted in marriage and family institutions, religious practices, social and economic systems, cultural values and legal system and so on. However, the eventual contact with Western culture through colonialism and, with the subsequent upsurge of globalization and modernity, these values are not only being challenged but also eroded. Consequent upon this onslaught on the Esan value systems by western values, which has been tagged “cultural imperialism”, with its affirmative, debilitating and disruptive impact, what would be the response of Esans to salvage their pristine values that shaped their society morally, economically, politically and religiously in the past. This paper is an attempt to make a critical evaluation of the western values viz-a-viz Esan value system, stressing that Esans have some valuable and enriching cultures that are worthy of preservation in the face of western cultural onslaught. The methodology adopted in this work is both primary and secondary sources. Keywords: Value System, Impact, Westernization, Critical Evaluation, Africa, Esan Society Introduction Esan people are in Edo State of Nigeria. -

The Dark Side of Migration Remittances and Development: the Case of Edo Sex Trade in Europe

Pécs Journal of International and European Law - 2016/I The Dark Side of Migration Remittances and Development: The Case of Edo Sex Trade in Europe Catherine Enoredia Odorige PhD Candidate, National University of Public Service Budapest Migrants’ remittances outflow to developing nations has gained wide attention in recent times. This is due to the fact that it has surpassed the amount in total aid money from developed nations to these developing nations. According to World Bank estimates in 2011 remittances by migrants in the United Kingdom to India is 4billion USD compared to 450million USD aid to the country in that same year1. When looked at in real terms it means how much impact these money can have on the developmental strides of developing countries in the long and short run. The remittance flow to developing nations in 2008 was put at 336 billion US dollars and in 2009 it was 316 billion US dollars from developed countries.2 These remittances have in no small way had increased positive impact on the ways of life of persons and relatives living in these less developed countries. It is a relief to many homes from the grip of intense poverty. But the question is how much of these remittances are from legitimate and morally right sources? This paper seeks to look at remittances from Europe to Edo state of the federal republic of Nigeria and analyse the possible sources of remittances that have had an impact on the lives of the peoples of Edo state. Keywords: migration, remittances, human trafficking, human traffickers and sex trade. -

African, Oceanic and Pre-Columbian Art Thursday May 15, 2014 New York

African, Oceanic and Pre-Columbian Art Thursday May 15, 2014 New York African, Oceanic and Pre-Columbian Art Thursday May 15, 2014 at 1pm New York Bonhams Inquiries Automated Results Service 580 Madison Avenue Fredric Backlar, Specialist +1 (800) 223 2854 New York, New York 10022 +1 (323) 436 5416 bonhams.com +1 (212) 644 9001 (after May 6) Online bidding will be available [email protected] for this auction. For further Preview information please visit: Sunday May 11, 12pm to 5pm Rae Smith, Business Manager www.bonhams.com/21475 Monday May 12, 10am to 7pm +1 (323) 436 5412 Tuesday May 13, 10am to 5pm +1 (212) 644 9001 (after May 7) Please see pages 2 to 5 Wednesday May 14, 10am to 5pm [email protected] for bidder information including Thursday May 15, 10am to 1pm Conditions of Sale, after-sale collection and shipment. Bids +1 (212) 644 9001 Illustrations +1 (212) 644 9009 fax Front cover: Lot 75 First session page: Lot 17 To bid via the internet please Second session page: Lot 98 visit www.bonhams.com Third session page: Lot 186 Back cover: Lot 183 Sale Number: 21475 Lots 1 - 201 Catalog: $35 © 2014, Bonhams & Butterfields Auctioneers Corp.; All rights reserved. Bond No. 57BSBGL0808 Principal Auctioneer: Malcolm J. Barber, License No. 1183017 CONDITIONS OF SALE The following Conditions of Sale, as amended by any liable for the payment of any deficiency plus all costs and 9. The copyright in the text of the catalog and the published or posted notices or verbal announcements expenses of both sales, our commission at our standard photographs, digital images and illustrations of lots in during the sale, constitute the entire terms and rates, all other charges due hereunder, attorneys’ fees, the catalog belong to Bonhams or its licensors. -

Perspectives on Nigerian Peoples and Culture

Perspect ives on Nigerian Peoples and Cult ure i ii Perspectives on Nigerian Peoples and Culture Edited by Joh n E. A gaba Chris S. Orngu iii © Department of History, Benue State University, Makurdi, 2016 All rights Reserved. This book is copyright and so no part of it should be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner (Department of H istory, Benue State U niversity, M akurdi). ISBN: 978-978-954-726-5 A Publication of the Department of History, Benue State University, Makurdi, Nigeria. Department of History, BSU Publication Series No. 1, 2016 iv Dedication Our Students v Acknowledgements We acknowledge the contributors for their collective resourcefulness in putting this volume together. We also deeply appr eci at e t h e sch ol ar s w h ose or i gi n al i deas h ave added val u e t o the chapters in this volume. vi Contents Dedication v Acknow;edgements vi Contents vii Foreword ix Chapter One Conceptual Perspectives of Culture Chris Orngu 1 Chapter Two Notable Ethnic Groups in Northern Nigeria Terwase T. Dzeka and Emmanuel S. Okla 7 Chapter Three Notable Ethnic Group in Southern Nigeria Toryina A. Varvar and Faith O. Akor 22 Chapter Four Culture Zones in Nigeria Armstrong M. Adejo and Elijah Terdoo Ikpanor 36 Chapter Five Traditional Crafts and Cultural Festivals in N igeria Emmanuel C. Ayangaor 53 Chapter Six The Evolution of the Nigerian State Saawua G. -

Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting in Nigeria: a Scoping Review

FEMALE GENITAL MUTILATION/CUTTING IN NIGERIA: A SCOPING REVIEW May 2017 FEMALE GENITAL MUTILATION/CUTTING IN NIGERIA: A SCOPING REVIEW BLESSING UCHENNA MBERU AFRICAN POPULATION AND HEALTH RESEARCH CENTRE MAY 2017 The Evidence to End FGM/C: Research to Help Girls and Women Thrive generates evidence to inform and influence investments, policies, and programmes for ending female genital mutilation/cutting in different contexts. Evidence to End FGM/C is led by the Population Council, Nairobi in partnership with the Africa Coordinating Centre for the Abandonment of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (ACCAF), Kenya; the Gender and Reproductive Health & Rights Resource Center (GRACE), Sudan; the Global Research and Advocacy Group (GRAG), Senegal; Population Council, Nigeria; Population Council, Egypt; Population Council, Ethiopia; MannionDaniels, Ltd. (MD); Population Reference Bureau (PRB); University of California, San Diego (Dr. Gerry Mackie); and University of Washington, Seattle (Prof. Bettina Shell-Duncan). The Population Council confronts critical health and development issues—from stopping the spread of HIV to improving reproductive health and ensuring that young people lead full and productive lives. Through biomedical, social science, and public health research in 50 countries, we work with our partners to deliver solutions that lead to more effective policies, programmes, and technologies that improve lives around the world. Established in 1952 and headquartered in New York, the Council is a nongovernmental, nonprofit organisation governed by an international board of trustees. www.popcouncil.org Suggested Citation: Blessing Uchenna Mberu “Female genital mutilation/cutting in Nigeria: A scoping review. May 2017,” Evidence to End FGM/C: Research to Help Women Thrive. New York: Population Council, http://www.popcouncil.org/ uploads/pdfs/2017RH_FGMC-NigeriaScopingReview.pdf.