Copyright by Indulata Prasad May 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contributions of Lala Har Dayal As an Intellectual and Revolutionary

CONTRIBUTIONS OF LALA HAR DAYAL AS AN INTELLECTUAL AND REVOLUTIONARY ABSTRACT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF ^ntiat ai pijtl000pi{g IN }^ ^ HISTORY By MATT GAOR CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2007 ,,» '*^d<*'/. ' ABSTRACT India owes to Lala Har Dayal a great debt of gratitude. What he did intotality to his mother country is yet to be acknowledged properly. The paradox ridden Har Dayal - a moody idealist, intellectual, who felt an almost mystical empathy with the masses in India and America. He kept the National Independence flame burning not only in India but outside too. In 1905 he went to England for Academic pursuits. But after few years he had leave England for his revolutionary activities. He stayed in America and other European countries for 25 years and finally returned to England where he wrote three books. Har Dayal's stature was so great that its very difficult to put him under one mould. He was visionary who all through his life devoted to Boddhi sattava doctrine, rational interpretation of religions and sharing his erudite knowledge for the development of self culture. The proposed thesis seeks to examine the purpose of his returning to intellectual pursuits in England. Simultaneously the thesis also analyses the contemporary relevance of his works which had a common thread of humanism, rationalism and scientific temper. Relevance for his ideas is still alive as it was 50 years ago. He was true a patriotic who dreamed independence for his country. He was pioneer for developing science in laymen and scientific temper among youths. -

List of Roll Numbers for 'Ayurvedic Pharmacist-470' Examination Date 4.9.2016 (10 AM to 12 Noon)

List of Roll Numbers for 'Ayurvedic Pharmacist-470' Examination date 4.9.2016 (10 AM to 12 Noon) Applicatio Name of Father/Husba DOB Roll No Examination Centre n ID Candidate nd Name 81004 NEENA DEVI SHAMSHER 18/02/1984 470000001 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre SINGH One, District Hamirpur (HP) 69728 Dinesh S/O: Babu 12/4/1990 470000002 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre Kumar Ram One, District Hamirpur (HP) 24497 Sameena W/O Sher 17/03/1986 470000003 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre Devi Khan One, District Hamirpur (HP) 31483 Kamal S/O Jagdish 29/11/1984 470000004 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre Kumar Singh One, District Hamirpur (HP) 35534 Indu Bala D/O Vikram 7/2/1986 470000005 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre Kashyap Singh One, District Hamirpur (HP) 61994 Sunil Kumar S/O Tulsi Ram 15/11/1982 470000006 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre One, District Hamirpur (HP) 31257 Vinod Kumar S/O Amar 23/09/1984 470000007 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre Singh One, District Hamirpur (HP) 30989 Anil Kumar S/O Pratap 27/07/1986 470000008 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre Singh One, District Hamirpur (HP) 38835 Usha Devi Nikka Ram 19/11/1989 470000009 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre One, District Hamirpur (HP) 106612 Sushma W/O Rajesh 9/10/1983 470000010 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre Kumari Kumar One, District Hamirpur (HP) 51251 PRAVEEN JAVAHIR 12/8/1993 470000011 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre YADAV SINGH YADAV One, District Hamirpur (HP) 37051 Suresh S/O Baldev 15/07/1983 470000012 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre Kumar Dass One, District Hamirpur (HP) 20316 Anju Devi D/O Suram 5/12/1988 470000013 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre Singh One, District Hamirpur (HP) 51530 Sushma Govind Ram 13/04/1990 470000014 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre Kamal One, District Hamirpur (HP) 62270 Sharmila D/O Tulsi Ram 29/03/1985 470000015 Gautam College Hamirpur Centre Kumari One, District Hamirpur (HP) 24854 SANDEEP SH. -

Village & Townwise Primary Census Abstract, Yamunanagar, Part XII A

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES -8 HARYANA DISTRICT CEN.SUS HANDBOOK PART XII - A & B VILLAGE & TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE &TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT DISTRICT YAMUNANAGAR Direqtor of Census Operations Haryana Published by : The Government of Haryana. 1995 ir=~~~==~==~==~====~==~====~~~l HARYANA DISTRICT YAMUNANAGAR t, :~ Km 5E3:::a::E0i:::=::::i====310==::::1i:5==~20. Km C.O.BLOCKS A SADAURA B BILASPUR C RADAUR o JAGADHRI E CHHACHHRAULI C.D.BLOCK BOUNDARY EXCLUDES STATUTORY TOWN (S) BOUNDARIES ARE UPDATED UPTO 1.1.1990 W. R.C. WORKSHOP RAILWAY COLONY DISTRICT YAMUNANAGAR CHANGE IN JURI50lC TION 1981-91 KmlO 0 10 Km L__.j___l BOUNDARY, STATE ... .. .. .. _ _ _ DISTRICT _ TAHSIL C D. BLOCK·:' .. HEADQUARTERS: DISTRICT; TAHSIL; e.D. BLOCK @:©:O STATE HIGHWAY.... SH6 IMPORT ANi MEiALLED ROAD RAILWAY LINE WITH STATION. BROAD GAUGE RS RIVER AND STREAMI CANAL ~/--- - Khaj,wan VILLAGE HAVING 5000 AND ABOVE POPULATION WITH NAME - URBAN AREA WITH POPULATION SIZE-CLASS I,II,IV &V .. POST AND TElEGRAPH OFFICE. PTO DEGREE COLLEGE AND TECHNICAL INSTITUTION ... ••••1Bl m BOUNDARY, STATE DISTRICT REST HOUSE, TRAVELLERS' BUNGALOW, FOREST BUNGALOW RH TB rB CB TA.HSIL AND CANAL BUNGALOW NEWLY CREATED DISTRICT YAMuNANAGAR Other villages having PTO/RH/TB/FB/CB, ~tc. are shown as .. .Damla HAS BEEN FORMED BY TRANSFERRING PTO AREA FROM :- Western Yamuna Canal W.Y.C. olsTRle T AMBAl,A I DISTRICT KURUKSHETRA SaSN upon Survt'y of India map with tn. p.rmission of theo Survt'yor Gf'nf'(al of India CENSUS OF INDIA - 1991 A - CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS The publications relating to Haryana bear series No. -

Gaya Travel Guide - Page 1

Gaya Travel Guide - http://www.ixigo.com/travel-guide/gaya page 1 and Nagkut Mountain. Brahmayoni offers a Max: 31.0°C Min: Rain: 8.0mm 19.20000076 sensational view of the plains. Shopaholics 2939453°C Gaya must visit the famous G B Road and May One of the most important cities in Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen. Reaching Gaya is easy as it is well-connected India, Gaya is also known as the Max: 34.0°C Min: Rain: 20.0mm to other regions through rail, road and air. 22.60000038 land of Vishnu and Buddhism. It 1469727°C Bodhgaya is the nearest airport from where Jun serves as the second largest city of a large number of international flights for Bihar after Patna and brings a lot of Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, Thailand, Japan and Myanmar ply on a daily umbrella. tourism to the state. Famous For : City basis. You can also travel to Patna, which is Max: 33.0°C Min: Rain: 137.0mm around 125 km from Gaya and has direct 21.89999961 8530273°C Gaya is of great religious importance to trains for Kolkata, Delhi and Mumbai. Jul Hindus and Buddhists and is home to Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, numerous ancient temples and When To umbrella. archaeological sites. An amalgamation of Max: 29.5°C Min: Rain: 315.0mm 21.10000038 age-old cultures and modern lifestyle, this 1469727°C city is a must-visit for all the travellers. From VISIT Aug three sides it is surrounded by small rocky Pleasant weather. -

University of Washington A0007 B0007

U.S. Department of Education Washington, D.C. 20202-5335 APPLICATION FOR GRANTS UNDER THE National Resource Centers and Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowships CFDA # 84.015A PR/Award # P015A180007 Gramts.gov Tracking#: GRANT12653993 OMB No. , Expiration Date: Closing Date: Jun 25, 2018 PR/Award # P015A180007 **Table of Contents** Form Page 1. Application for Federal Assistance SF-424 e3 2. Standard Budget Sheet (ED 524) e6 3. Assurances Non-Construction Programs (SF 424B) e8 4. Disclosure Of Lobbying Activities (SF-LLL) e10 5. ED GEPA427 Form e11 Attachment - 1 (1242-UW SAC GEPA) e12 6. Grants.gov Lobbying Form e19 7. Dept of Education Supplemental Information for SF-424 e20 8. ED Abstract Narrative Form e21 Attachment - 1 (1243-UW SAC ABSTRACT) e22 9. Project Narrative Form e24 Attachment - 1 (1241-UW SAC PROJECT NARRATIVE) e25 10. Other Narrative Form e80 Attachment - 1 (1235-UW SAC APPLICANT PROFILE) e81 Attachment - 2 (1236-UW SAC DIVERSE PERSPECTIVES AND AREAS OF NATIONAL NEED) e82 Attachment - 3 (1237-UW SAC APPENDIX B (CV AND POSITION DESCRIPTIONS)) e84 Attachment - 4 (1238-UW SAC APPENDIX C (COURSE LIST)) e137 Attachment - 5 (1239-UW SAC APPENDIX D (PMFs)) e147 Attachment - 6 (1240-UW SAC LETTERS OF SUPPORT) e154 11. Budget Narrative Form e160 Attachment - 1 (1234-UW SAC BUDGET NARRATIVE) e161 This application was generated using the PDF functionality. The PDF functionality automatically numbers the pages in this application. Some pages/sections of this application may contain 2 sets of page numbers, one set created by the applicant and the other set created by e-Application's PDF functionality. -

Department of Drugs Control License Register

License Register Department of Drugs Control Firm: 10158 To: 41190 Sr/Firm No Firm Name , I.C / Manager Firm Address Issue Dt Cold Stor. 24 Hr Open District / R.Pharmacist , Competent Person Renewal Dt Lic App Firm Cons Inspection Dt Circle:Ludhiana 1 / R a.nand medical hall/ vpo saloudi,saloudi, 30/07/2001 - - YES/NO 22333 nirmal singh/ tehsil samrala-141114 SATISH KUMAR LD5 d.pharm PAR No R.P/No C.P Phon No:9855247152,9872173763,SAM *** 20-14639/NB~31/12/17 *** 21-14639/B~31/12/17 2 / R abhi medicos/ village garhi tarkhana,po. macchiwara, - 11/01/2018 - YES/NO 17342 gurmit lal/ tehsil samrala-141114 GURMIT LAL LD5 gurmit lal s/o kashmira lal resident of PRO 28633-nikhil shah/No C.P Phon No:9988917400,9988917400,SAM village shamgarh tehsil samrala distt ludhiana *** 20-128392~10/01/23 *** 21-128393~10/01/23 3 / R ahuja medical store/ vpo behlolpur,behlolpur, 25/03/2002 - 25/03/2017 - 15/03/2017 YES/NO 16202 gurbinder singh/ tehsil samrala-141114 GURBINDER SINGH LD5 d.pharm PRO 12252-gurbinder singh/No C.P Phon No:9592263566,9592263566,SAM *** 20-113505~24/03/22 *** 21-113506~24/03/22 4 / R aman medical store/ malerkotla road,guru harkrishan nagar, 22/05/2014 - 01/03/2019 - YES/NO 15072 vinod kumar/ khanna-141401 VINOD KUMAR LD5 PAR 32768-pawan kumar/No C.P Phon No:9855006172,9855506172,KH1 *** 20-139663~29/02/24~09/10/17 *** 21-139664~29/02/24~09/10/17 5 / R aman medical store/ village khanna khurd,khanna khurd, 10/05/2017 - 10/05/2017 - 05/05/2017 NO/NO 34718 harbhinder singh/ tehsil khanna, distt. -

Soorma’ Puts up a Good Fight 3% DA for Punjab Govt the Police with Help of Withdrawals at Rs 25,000

123 chandigarh | gurugram | jalandhar | bathinda | jammu | srinagar | vol.3 no.283 | 26 pages | ~5.00 | regd.no.chd/0006/2018-2020 established in 1881 SENA WOOS VOTERS WITH GURU NANAK TEACHINGS TRANSCEND TIME KIPCHOGE BREACHES 2-HR ~10 MEALS NATION SPECTRUM MARATHON BARRIER SPORT /thetribunechd /thetribunechd www.tribuneindia.com sunday, october 13,2019 India, China to set up trade mechanism Policy holding back benefits to NEW MOMENTUM Will enhance defence & security ties| No mention of Kashmir war wounded to be corrected Sandeep Dikshit AjayBanerjee Here comes the catch. The Tribune News Service MODI GIFTS SILK Tribune News Service THE 2014 TWEAK battle casualty and war wound- Mamallapuram, October 12 SHAWL TO PREZ XI NewDelhi, October 12 While those under the ‘low ed classified as ‘LMC’ under India and China have decid- An erroneous policy of the the 2012 policy get weightage Prime Minister Modi gifted a medical category’ continue ed to set up a high-level Indian Army is holding back to get benefits, in 2014 the for promotions, fee exemption mechanism on trade and handmade silk shawl to benefits to a particular of children’s education, reser- Chinese President Xi Jinping. Army policy was tweaked, investment and focus more category of personnel wound- vation in educational institu- The shawl has zari laying out that benefits on defence and security ties. embellishment of Xi’s image ed in war, including those who would be stopped to war tions, income tax exemptions The biggest takeaway from in gold against bright red were hit by the enemy bullet wounded who had and preference in foreign post- the two-day India-China sec- silk background. -

Prof. S. M. S. Chahal Curriculum Vitae 1. Name : Sukh Mohinder Singh

Prof. S. M. S. Chahal Curriculum Vitae 1. Name : Sukh Mohinder Singh Chahal 2. Designation : Professor (Re- employed) 3. Department : Human Genetics 4. Date of Birth : 24.07.1955 5. Residential Address : A-9 Campus, Punjabi University, Patiala Correspondence Address : Department of Human Genetics, Punjabi University, Patiala 147 002, Punjab (India) Telephones : (0175) 2286304 (Residence) (0175) 3046277 (Office) Cell phone : 09876096304 e-mail : [email protected] [email protected] 6. Areas of Specialization : Human Biochemical and Population Genetics/ Biological Anthropology 7. Academic Qualifications S. Degree Year Board / University % of Division/ Subjects No. held marks taken Rank 1 Ph. D. 1981 University of - - Human Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Genetics England 2 M. Sc. 1976 University of Delhi, 60.4 First/ Physical Delhi Anthropology 3 B. Sc. 1974 University of Delhi, 59.4 High Zoology, Delhi Second Chemistry, Botany 4. Pre- 1972 University of Delhi, 61.1 First Zoology, Medical Delhi Botany, Chemistry, English 5. Higher 1971 C.B.S.E., New Delhi 69.3 First Biology, Secondary Physics, Chemistry, English 8. Membership of Professional Bodies/ Organizations Life Member, Indian Anthropological Society, Calcutta Life Member, Genetic Association of India, Bareilly Life Member, Indian Anthropological Association, Delhi Life Member, Ethnographic and Folk Cultural Society, Lucknow Life Member, Indian Society for Human Ecology, Delhi Life Member, Punjab Academy of Sciences, Patiala Life Member, Indian National Confederation and Academy of Anthropologists (INCAA), Kolkata Member, Indian Science Congress Association (ISCA), Calcutta Member, International Association of Human Biologists (IAHB) 9. Medals/ Awards/ Honours/ Received Secured IIIrd position in M.Sc. (Anthropology) examination of University of Delhi, Delhi (1976). -

Evening & Weekend

Evening & Weekend MBA Student Facebook 2018-2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS CLASS OF 2019 ...............................................................................................................3 CLASS OF 2020 ............................................................................................................ 28 CLASS OF 2021 ............................................................................................................ 49 Evening & Weekend MBA Staff Program Office Staff ................................................................................................ 70 Admissions Staff .......................................................................................................71 Lifecycle Staff ............................................................................................................72 First Name Index .........................................................................................................74 EVENING & WEEKEND MBA PROGRAM MBA WEEKEND & EVENING 1 CLASS OF 2019 OF CLASS Suraj Abraham Melanie Akwule Nvidia Corporation GE Digital Senior Hardware Engineer Technical Product Manager, National Institute of Data & Analytics Technology, Karnataka Georgia Tech Electronics and Business Administration Communication 14903 15219 Soumya Aladi Jane Alston HEARST Health - FDB David Grant Medical Center Product Success Manager General Surgeon National Institute of 14623 Technology, Kurukshetra Electrical Engineering 14904 Ganesh Alwarsamy Jon Amadei Cognizant Technology Square, Inc. Solutions -

Gaya Water Supply Phase 1 (GWSP1) Subproject

Initial Environmental Examination Document Stage: Draft Project Number: 41603-024 May 2017 IND: Bihar Urban Development Investment Program — Gaya Water Supply Phase 1 (GWSP1) Subproject Prepared by Urban Development and Housing Department, Government of Bihar for the Asian Development Bank. This draft initial environmental examination report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. ABBREVIATIONS ADB — Asian Development Bank BOQ — bill of quantity BPLE — Bihar Public Land Encroachment Act BSPCB — Bihar State Pollution Control Board, BUIDCo — Bihar Urban Infrastructure Development Corporation BUDIP — Bihar Urban Development Investment Program C & P — consultation and participation CBO — community-based organization CFE — Consent for Establishment CFO — Consent for Operation CGWB — Central Ground Water Board CITES Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species — of Wild Fauna and Flora CMS — Convention on Migratory Species of Wild Animals CWR — clear water reservoir DFO — Divisional Forest Officer DSC — design and supervision consultants EAC — Expert Appraisal Committee EARF — environmental assessment -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details State Incapacity by Design Unused Grants, Poverty and Electoral Success in Bihar Athakattu Santhosh Mathew A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy from the University of Sussex Institute of Development Studies University of Sussex December 2011 ii I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature: iii UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX ATHAKATTU SANTHOSH MATHEW DPHIL DEVELOPMENT STUDIES STATE INCAPACITY BY DESIGN Unused Grants, Poverty and Electoral Success in Bihar SUMMARY This thesis offers a perspective on why majority-poor democracies might fail to pursue pro- poor policies. In particular, it discusses why in Bihar, the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) party led by Lalu Prasad Yadav, which claimed to represent the poor and under-privileged, did not claim and spend large amounts of centre–state fiscal transfers that could have reduced poverty, provided employment and benefitted core supporters. -

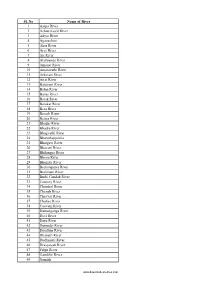

List of Rivers in India

Sl. No Name of River 1 Aarpa River 2 Achan Kovil River 3 Adyar River 4 Aganashini 5 Ahar River 6 Ajay River 7 Aji River 8 Alaknanda River 9 Amanat River 10 Amaravathi River 11 Arkavati River 12 Atrai River 13 Baitarani River 14 Balan River 15 Banas River 16 Barak River 17 Barakar River 18 Beas River 19 Berach River 20 Betwa River 21 Bhadar River 22 Bhadra River 23 Bhagirathi River 24 Bharathappuzha 25 Bhargavi River 26 Bhavani River 27 Bhilangna River 28 Bhima River 29 Bhugdoi River 30 Brahmaputra River 31 Brahmani River 32 Burhi Gandak River 33 Cauvery River 34 Chambal River 35 Chenab River 36 Cheyyar River 37 Chaliya River 38 Coovum River 39 Damanganga River 40 Devi River 41 Daya River 42 Damodar River 43 Doodhna River 44 Dhansiri River 45 Dudhimati River 46 Dravyavati River 47 Falgu River 48 Gambhir River 49 Gandak www.downloadexcelfiles.com 50 Ganges River 51 Ganges River 52 Gayathripuzha 53 Ghaggar River 54 Ghaghara River 55 Ghataprabha 56 Girija River 57 Girna River 58 Godavari River 59 Gomti River 60 Gunjavni River 61 Halali River 62 Hoogli River 63 Hindon River 64 gursuti river 65 IB River 66 Indus River 67 Indravati River 68 Indrayani River 69 Jaldhaka 70 Jhelum River 71 Jayamangali River 72 Jambhira River 73 Kabini River 74 Kadalundi River 75 Kaagini River 76 Kali River- Gujarat 77 Kali River- Karnataka 78 Kali River- Uttarakhand 79 Kali River- Uttar Pradesh 80 Kali Sindh River 81 Kaliasote River 82 Karmanasha 83 Karban River 84 Kallada River 85 Kallayi River 86 Kalpathipuzha 87 Kameng River 88 Kanhan River 89 Kamla River 90