Towards a Cognitive Linguistic Theology of Sacrifice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meet the Gilded Lady 2 Mummies Now Open

Member Magazine Spring 2017 Vol. 42 No. 2 Mummies meet the gilded lady 2 mummies now open Seeing Inside Today, computerized inside of mummies, revealing CT scans of the Gilded Lady tomography (CT) scanning details about the person’s reveal that she was probably offers researchers glimpses age, appearance, and health. in her forties. They also suggest of mummified individuals “Scans like these are noninvasive, that she may have suffered like never before. By combining they’re repeatable, and they from tuberculosis, a common thousands of cross-sectioned can be done without damaging disease at the time. x-ray images, CT scans let the history that we’re trying researchers examine the to understand,” Thomas says. Mummy #30007, known as the Gilded Lady, is one of the most beautifully preserved mummies from The Field Museum’s collection, and one of 19 now on view in the special exhibition Mummies. For decades, keeping mummies like this one well preserved also meant severely limiting the ability of researchers to study them. The result is that little was known about the Gilded Lady beyond what could be gleaned from the mummy’s exterior, with its intricate linen bindings, gilded headdress, and painted facial features. Exterior details do offer some clues. The mummy dates from 30 BC–AD 395, a period when Egypt was a province of the Roman Empire. While the practice of mummification endured in Egypt, it was being transformed by Roman influences. Before the Roman era, for example, mummies had been placed in wooden coffins, while the Gilded Lady is preserved in only linen wrappings and cartonnage, a papier mâché-like material. -

Place Names Describing Fossils in Oral Traditions

Place names describing fossils in oral traditions ADRIENNE MAYOR Classics Department, Stanford University, Stanford CA 94305 (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract: Folk explanations of notable geological features, including fossils, are found around the world. Observations of fossil exposures (bones, footprints, etc.) led to place names for rivers, mountains, valleys, mounds, caves, springs, tracks, and other geological and palaeonto- logical sites. Some names describe prehistoric remains and/or refer to traditional interpretations of fossils. This paper presents case studies of fossil-related place names in ancient and modern Europe and China, and Native American examples in Canada, the United States, and Mexico. Evidence for the earliest known fossil-related place names comes from ancient Greco-Roman and Chinese literature. The earliest documented fossil-related place name in the New World was preserved in a written text by the Spanish in the sixteenth century. In many instances, fossil geonames are purely descriptive; in others, however, the mythology about a specific fossil locality survives along with the name; in still other cases the geomythology is suggested by recorded traditions about similar palaeontological phenomena. The antiquity and continuity of some fossil-related place names shows that people had observed and speculated about miner- alized traces of extinct life forms long before modern scientific investigations. Traditional place names can reveal heretofore unknown geomyths as well as new geologically-important sites. Traditional folk names for geological features in the Named fossil sites in classical antiquity landscape commonly refer to mythological or and modern Greece legendary stories that accounted for them (Vitaliano 1973). Landmarks notable for conspicuous fossils Evidence for the practice of naming specific fossil have been named descriptively or mythologically locales can be found in classical antiquity. -

Viruses and the Origin of Microbiome Selection and Immunity

The ISME Journal (2017) 11, 835–840 © 2017 International Society for Microbial Ecology All rights reserved 1751-7362/17 www.nature.com/ismej PERSPECTIVE Viruses and the origin of microbiome selection and immunity Steven D Quistad1,2,3, Juris A Grasis1, Jeremy J Barr1,4 and Forest L Rohwer1 1Department of Biology, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA, USA; 2Laboratoire de Colloïdes et Matériaux Divisés (LCMD), Institute of Chemistry, Biology, and Innovation, ESPCI ParisTech/CNRS UMR 8231/PSL Research University, Paris, France; 3Laboratoire de Colloïdes et Matériaux Divisés (LCMD), Institute of Chemistry, Biology, and Innovation, ESPCI ParisTech/CNRS UMR 8231/PSL Research University, Paris, France and 4School of Biological Sciences, Monash University, Clayton, Victoria 3800, Australia The last common metazoan ancestor (LCMA) emerged over half a billion years ago. These complex metazoans provided newly available niche space for viruses and microbes. Modern day contemporaries, such as cnidarians, suggest that the LCMA consisted of two cell layers: a basal endoderm and a mucus-secreting ectoderm, which formed a surface mucus layer (SML). Here we propose a model for the origin of metazoan immunity based on external and internal microbial selection mechanisms. In this model, the SML concentrated bacteria and their associated viruses (phage) through physical dynamics (that is, the slower flow fields near a diffusive boundary layer), which selected for mucin-binding capabilities. The concentration of phage within the SML provided the LCMA with an external microbial selective described by the bacteriophage adherence to mucus (BAM) model. In the BAM model, phage adhere to mucus protecting the metazoan host against invading, potentially pathogenic bacteria. -

Issue of the FOSSIL

Official Publication of The Fossils, The Historians of Amateur Journalism The Fossil Volume 116, No. 3, Whole No. 383 Sunnyvale, California April 2020 Fossil Profile My Ajay Mentors by Linda Donaldson FOSSIL EDITOR Dave Tribby has asked me to provide a the beginning of a long love affair. It was almost the few thoughts on my friends and mentors in the world last press I saw exit my door. of amateur journalism. Though I’m not active now, He also introduced me to ajayers in my hometown thanks mostly to vision problems that make it hard to of Portsmouth, Ohio: Karl X. Williams and Charlie read the bundles, I was fortunate Phillips. The two of them were to have had several good men happy to share or sell me some of tors. I am still a Fossil—it’s hard their treasure troves of type or to totally desert the realm. necessary equipment. Much has It started with the one and been written of Karl, a Lone only J. Hill Hamon, whom I met Scout young printer in the 1920s, as my Biology professor at AAPA founding father, and a Transylvania University in Lex Fossil. To this day I possess a pa ington, Kentucky in January of per cutter I bought from Katie, 1972. I didn’t start learning the Karl’s widow. I was employed printing part until a short term about five years as a rubber class in December of 1972. He set stamp maker by Karl’s daughter out lots of old type on the Bio Pam and soninlaw Gary. -

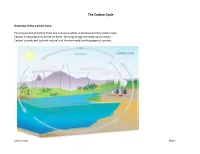

The Carbon Cycle

The Carbon Cycle Overview of the Carbon Cycle The movement of carbon from one area to another is the basis for the carbon cycle. Carbon is important for all life on Earth. All living things are made up of carbon. Carbon is produced by both natural and human-made (anthropogenic) sources. Carbon Cycle Page 1 Nature’s Carbon Sources Carbon is found in the Carbon is found in the lithosphere Carbon is found in the Carbon is found in the atmosphere mostly as carbon in the form of carbonate rocks. biosphere stored in plants and hydrosphere dissolved in ocean dioxide. Animal and plant Carbonate rocks came from trees. Plants use carbon dioxide water and lakes. respiration place carbon into ancient marine plankton that sunk from the atmosphere to make the atmosphere. When you to the bottom of the ocean the building blocks of food Carbon is used by many exhale, you are placing carbon hundreds of millions of years ago during photosynthesis. organisms to produce shells. dioxide into the atmosphere. that were then exposed to heat Marine plants use cabon for and pressure. photosynthesis. The organic matter that is produced Carbon is also found in fossil fuels, becomes food in the aquatic such as petroleum (crude oil), coal, ecosystem. and natural gas. Carbon is also found in soil from dead and decaying animals and animal waste. Carbon Cycle Page 2 Natural Carbon Releases into the Atmosphere Carbon is released into the atmosphere from both natural and man-made causes. Here are examples to how nature places carbon into the atmosphere. -

The Mummy of All Dinosaurs Compare and Contrast Careful Work

Careful Work © Clipart.com Scientists are very careful when they © iClipart work on dinosaur presented by Science a-z a division of Learning A-Z fossils. They use bright The Mummy of All Dinosaurs lights and small tools. By Jane Sellman They use toothbrushes March 2008: Scientists have found the most to clean away dirt. complete dinosaur mummy ever. A dinosaur They do not want to © Louis Tremblay mummy is a kind of fossil. A fossil is a living hurt the fossils! It thing that died and turned into rock. A mummy takes a long time to Tyler Lyson, who found the dinosaur fossil has bones and skin or muscles. With this uncover a fossil. mummy, works on a fossil. mummy, even the insides turned into rock. Scientists are Compare and Contrast learning amazing things from this mummy. © National Geographic Television Art and Animation, © National Geographic Television Julius T. Csotonyi and 3D model by 422 South Julius T. Scientists have T. rex Hadrosaur learned that • Length: 40’ • Length: 36’ dinosaurs were • Speed: 20 mph • Speed: 28 mph © Louis Tremblay • Teeth: pointed for • Teeth: flat for even bigger than tearing meat chewing plants we thought! How else can you compare these two dinosaurs? See Mummy of All Dinos Tyler Lyson (on the right) uses a jackhammer © BigStockPhoto, Digital Studio on page 2 to remove rock from around fossils. © Learning A–Z, Inc. All rights reserved. 4 www.sciencea-z.com 1 Mummy of All Dinos Continued from page 1 Writing Prompt: There was a little space between each piece of How is this the mummy’s backbone. -

Fossil Record – Timing of Events and Extinction

Biology 1B—Evolution Lecture 11, Insights from the Fossil Record – timing of events and extinction Fossil Record (speciation) Microevolution Macroevolution The fossil record is our primary source of information on the past, including the timing of various extinction and evolutionary events and the phenotypes of ancestral forms. Sedimentary rocks created by erosion (often in a marine environment) form strata, with different layers corresponding to different time periods. Consider the Grand Canyon, formed by the Colorado River over 20 million years: the exposed strata, from the top of nearby Bryce Canyon to the bottom of the Grand Canyon itself, cover the last billion years. These layers can be dated by analyzing proportions of different isotopes present in each of the strata. Fossils provided both key evidence and frustration to Darwin when writing the Origin of the Species. Fossils showed there were many creatures which no longer existed; but these animals existed at some point, and must have been adapted to the environment in which they lived. This further reinforced the idea that the present and past are ruled by the same physical processes. However, it was frustrating in that many complex creatures seemed to suddenly appear in the fossil record, without preceding transitional forms. Darwin predicted that these gaps would be filled, and many of the gaps he predicted have now been filled. Some major transitions in earth history Billions of Years Ago Earth and Solar System formation 4.5 Earliest prokaryote fossils 3.5 Increase in oxygen – implies photosynthesis 2.7 Single-celled fossil eukaryotes 2.1-1.2 Complex metazoan (multi-celled animals) 0.5 Hominids (apes and humans) 0.005 The Cambrian Explosion is a time period from 550 million years ago (appearance of complex metazoans) when many species and new body forms appear in the fossil record. -

Fueling Extinction: How Dirty Energy Drives Wildlife to the Brink

Fueling Extinction: How Dirty Energy Drives Wildlife to the Brink The Top Ten U.S. Species Threatened by Fossil Fuels Introduction s Americans, we are living off of energy sources produced That hasn’t stopped oil and gas companies from gobbling in the age of the dinosaurs. Fossil fuels are dirty. They’re up permits and leases for millions of acres of our pristine Adangerous. And, they’ve taken an incredible toll on our public land, which provides important wildlife habitat and country in many ways. supplies safe drinking water to millions of Americans. And the industry is demanding ever more leases, even though it is Our nation’s threatened and endangered wildlife, plants, birds sitting on thousands of leases it isn’t using—an area the size of and fish are among those that suffer from the impacts of our Pennsylvania. fossil fuel addiction in the United States. This report highlights ten species that are particularly vulnerable to the pursuit Oil companies have generated billions of dollars in profits, and of oil, gas and coal. Our outsized reliance on fossil fuels and paid their senior executives $220 million in 2010 alone. Yet the impacts that result from its development, storage and ExxonMobil, Chevron, Shell, and BP combined have reduced transportation is making it ever more difficult to keep our vow to their U.S. workforce by 11,200 employees since 2005. protect America’s wildlife. The American people are clearly getting the short end of the For example, the Arctic Ocean is home to some of our most stick from the fossil fuel industry, both in terms of jobs and in beloved wildlife—polar bears, whales, and seals. -

BIASES in INTERPRETATION of the FOSSIL RECORD of CONODONTS by MARK A

[Special Papers in Palaeontology, 73, 2005, pp. 7–25] BETWEEN DEATH AND DATA: BIASES IN INTERPRETATION OF THE FOSSIL RECORD OF CONODONTS by MARK A. PURNELL* and PHILIP C. J. DONOGHUE *Department of Geology, University of Leicester, University Road, Leicester LE1 7RH, UK; e-mail: [email protected] Department of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Wills Memorial Building, Queens Road, Bristol BS8 1RJ, UK; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The fossil record of conodonts may be among and standing generic diversity. Analysis of epoch ⁄ stage-level the best of any group of organisms, but it is biased nonethe- data for the Ordovician–Devonian interval suggests that less. Pre- and syndepositional biases, including predation there is generally no correspondence between research effort and scavenging of carcasses, current activity, reworking and and generic diversity, and more research is required to bioturbation, cause loss, redistribution and breakage of ele- determine whether this indicates that sampling of the cono- ments. These biases may be exacerbated by the way in which dont record has reached a level of maturity where few genera rocks are collected and treated in the laboratory to extract remain to be discovered. One area of long-standing interest elements. As is the case for all fossils, intervals for which in potential biases and the conodont record concerns the there is no rock record cause inevitable gaps in the strati- pattern of recovery of different components of the skeleton graphic distribution of conodonts, and unpreserved environ- through time. We have found no evidence that the increas- ments lead to further impoverishment of the recorded ing abundance of P elements relative to S and M elements spatial and temporal distributions of taxa. -

Definition of a Fossil Is Less Than Does Not Necessarily Involve Any Min Scientific

educational activities, natu concept, "I am, therefore I exist," could be ral history programming, applied directly toward limiting our defini books, media and more. Each tion of the word fossil. For a fossil to be a individual has his or her own fossil it must exist, and therefore, it must be perception of a fossil. To preserved in some form or state. It should be many children fossil means noted that the use of the words p reserve and dinosaur. To a ranger at Pet preservation does not necessitate mineral rified Forest, a fossil may be replacement or chemical alteration. an object that visitors occa Does the degree or mode of preservation sionally collect illegally. To need to be incorporated into the definition a commercial dealer a fossil of a fossil? Do the remains from the past may mean dollars. Grandma need to be chemically replaced, recrystal- sometimes even calls lized or turned to stone (petrified) in order grandpa a fossil! What vari to be accepted as a fossil? Indeed, we can ables should be included in a answer "no" to both of these questions. The scientific definition of a fos fossil record includes many examples of sil? Likewise, what variables unaltered animal and plant remains. Con should be omitted from the versely, are the bones of a coyote that fell definition? into a Yellowstone hot spring a few years To begin on some com ago fossils? The mineral-rich waters of the mon ground, it is widely ac hot spring promote rapid mineralization of cepted that a fossil is evi recent bones. -

Evolution, Extinction and the Fossil Record Life of the Earth

7 Articles atmosphere, taking into account temperature, cloud cover, wind and rainfall. They found the warmer eddies in the Southern Ocean were typically 0.5°C warmer than their surroundings and the cold ones were 0.5°C colder than the water beyond. Throughout the South- ern Ocean, these temperature anomalies correspond to changes in cloud cover and water content, as well as the frequency and prob- ability of rainfall. The reason? They alter the flux of heat between the ocean and the atmosphere. In the atmosphere, low pressure systems are the ones that generate rainfall. As these systems pass cold-core eddies, which have less heat to release, the cloud cover drops, moisture declines and rainfall reduces by 2-6%. The converse is true for warm-core eddies, which stimulate rainfall in their local vicinity. As well as providing the fuel for rain-filled clouds, the oceans shape where rain forms and falls around the planet. The heat energy heist undertaken by the Northern Hemisphere as it harvests energy from the south drives the differences in rainfall either side of the equator. Eddies bud off large ocean currents, like the Gulf Stream, bringing packages And an eddy in the ocean is all that’s needed to create a small, but of cold water into warmer regions and pockets of warmer water into colder significant, change in the amount of rainfall close to the water mass. regions. These 10–100 km across masses of water have a big impact on local Combined, these studies highlight just how wonderfully connected wind and rainfall patterns. -

Issue 3 August, 2014 ______

__________The Paleontograph________ A newsletter for those interested in all aspects of Paleontology Volume 3 Issue 3 August, 2014 _________________________________________________________________ From Your Editor Hello All, I hope you’ve enjoyed your summer. It has been humid but not too warm here in the Northeast. I’ve just returned from Morocco, where it was very warm. My wife and I spent about a week touring the country and some of its fossil sites. This was a trip I’ve been dreaming about for years and I am very glad I made it. We did not make it to the Trilobite areas but we saw the Phosphate and Orthoceras areas. We met with diggers at their homes and toured factories where the black Orthocersas plates and other items are produced. We also visited some of the normal tourist areas including Marrakech and Casablanca. I’m about to head out to the Denver Show. I will be set up in the Coliseum so if any of you are at the show, please stop by my Lost World Fossils booth on the main floor and say hello. The Paleontograph was created in 2012 to continue what was originally the newsletter of The New Jersey Paleontological Society. The Paleontograph publishes articles, book reviews, personal accounts, and anything else that relates to Paleontology and fossils. Feel free to submit both technical and non-technical work. We try to appeal to a wide range of people interested in fossils. Articles about localities, specific types of fossils, fossil preparation, shows or events, museum displays, field trips, websites are all welcome.