Ecology of Passerine Birds Wintering at Utah Lake

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesotho Fourth National Report on Implementation of Convention on Biological Diversity

Lesotho Fourth National Report On Implementation of Convention on Biological Diversity December 2009 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ADB African Development Bank CBD Convention on Biological Diversity CCF Community Conservation Forum CITES Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species CMBSL Conserving Mountain Biodiversity in Southern Lesotho COP Conference of Parties CPA Cattle Post Areas DANCED Danish Cooperation for Environment and Development DDT Di-nitro Di-phenyl Trichloroethane EA Environmental Assessment EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EMP Environmental Management Plan ERMA Environmental Resources Management Area EMPR Environmental Management for Poverty Reduction EPAP Environmental Policy and Action Plan EU Environmental Unit (s) GA Grazing Associations GCM Global Circulation Model GEF Global Environment Facility GMO Genetically Modified Organism (s) HIV/AIDS Human Immuno Virus/Acquired Immuno-Deficiency Syndrome HNRRIEP Highlands Natural Resources and Rural Income Enhancement Project IGP Income Generation Project (s) IUCN International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources LHDA Lesotho Highlands Development Authority LMO Living Modified Organism (s) Masl Meters above sea level MDTP Maloti-Drakensberg Transfrontier Conservation and Development Project MEAs Multi-lateral Environmental Agreements MOU Memorandum Of Understanding MRA Managed Resource Area NAP National Action Plan NBF National Biosafety Framework NBSAP National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan NEAP National Environmental Action -

The Maloti Drakensberg Experience See Travel Map Inside This Flap❯❯❯

exploring the maloti drakensberg route the maloti drakensberg experience see travel map inside this flap❯❯❯ the maloti drakensberg experience the maloti drakensberg experience …the person who practices ecotourism has the opportunity of immersing him or herself in nature in a way that most people cannot enjoy in their routine, urban existences. This person “will eventually acquire a consciousness and knowledge of the natural environment, together with its cultural aspects, that will convert him or her into somebody keenly involved in conservation issues… héctor ceballos-lascuráin internationally renowned ecotourism expert” travel tips for the maloti drakensberg region Eastern Cape Tourism Board +27 (0)43 701 9600 www.ectb.co.za, [email protected] lesotho south africa Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife currency Maloti (M), divided into 100 lisente (cents), have currency The Rand (R) is divided into 100 cents. Most +27 (0)33 845 1999 an equivalent value to South African rand which are used traveller’s cheques are accepted at banks and at some shops www.kznwildlife.com; [email protected] interchangeably in Lesotho. Note that Maloti are not accepted and hotels. Major credit cards are accepted in most towns. Free State Tourism Authority in South Africa in place of rand. banks All towns will have at least one bank. Open Mon to Fri: +27 (0)51 411 4300 Traveller’s cheques and major credit cards are generally 09h00–15h30, Sat: 09h00–11h00. Autobanks (or ATMs) are www.dteea.fs.gov.za accepted in Maseru. All foreign currency exchange should be found in most towns and operate on a 24-hour basis. -

South Africa Mega Birding III 5Th to 27Th October 2019 (23 Days) Trip Report

South Africa Mega Birding III 5th to 27th October 2019 (23 days) Trip Report The near-endemic Gorgeous Bushshrike by Daniel Keith Danckwerts Tour leader: Daniel Keith Danckwerts Trip Report – RBT South Africa – Mega Birding III 2019 2 Tour Summary South Africa supports the highest number of endemic species of any African country and is therefore of obvious appeal to birders. This South Africa mega tour covered virtually the entire country in little over a month – amounting to an estimated 10 000km – and targeted every single endemic and near-endemic species! We were successful in finding virtually all of the targets and some of our highlights included a pair of mythical Hottentot Buttonquails, the critically endangered Rudd’s Lark, both Cape, and Drakensburg Rockjumpers, Orange-breasted Sunbird, Pink-throated Twinspot, Southern Tchagra, the scarce Knysna Woodpecker, both Northern and Southern Black Korhaans, and Bush Blackcap. We additionally enjoyed better-than-ever sightings of the tricky Barratt’s Warbler, aptly named Gorgeous Bushshrike, Crested Guineafowl, and Eastern Nicator to just name a few. Any trip to South Africa would be incomplete without mammals and our tally of 60 species included such difficult animals as the Aardvark, Aardwolf, Southern African Hedgehog, Bat-eared Fox, Smith’s Red Rock Hare and both Sable and Roan Antelopes. This really was a trip like no other! ____________________________________________________________________________________ Tour in Detail Our first full day of the tour began with a short walk through the gardens of our quaint guesthouse in Johannesburg. Here we enjoyed sightings of the delightful Red-headed Finch, small numbers of Southern Red Bishops including several males that were busy moulting into their summer breeding plumage, the near-endemic Karoo Thrush, Cape White-eye, Grey-headed Gull, Hadada Ibis, Southern Masked Weaver, Speckled Mousebird, African Palm Swift and the Laughing, Ring-necked and Red-eyed Doves. -

Multi-Locus Phylogeny of African Pipits and Longclaws (Aves: Motacillidae) Highlights Taxonomic Inconsistencies

Running head: African pipit and longclaw taxonomy Multi-locus phylogeny of African pipits and longclaws (Aves: Motacillidae) highlights taxonomic inconsistencies DARREN W. PIETERSEN,1* ANDREW E. MCKECHNIE,1,2 RAYMOND JANSEN,3 IAN T. LITTLE4 AND ARMANDA D.S. BASTOS5 1DST-NRF Centre of Excellence at the Percy FitzPatrick Institute, Department of Zoology and Entomology, University of Pretoria, Hatfield, South Africa 2South African Research Chair in Conservation Physiology, National Zoological Garden, South African National Biodiversity Institute, P.O. Box 754, Pretoria 0001, South Africa 3Department of Environmental, Water and Earth Sciences, Tshwane University of Technology, Pretoria, South Africa 4Endangered Wildlife Trust, Johannesburg, South Africa 5Department of Zoology and Entomology, University of Pretoria, Hatfield, South Africa *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] 1 Abstract The globally distributed avian family Motacillidae consists of 5–7 genera (Anthus, Dendronanthus, Tmetothylacus, Macronyx and Motacilla, and depending on the taxonomy followed, Amaurocichla and Madanga) and 66–68 recognised species, of which 32 species in four genera occur in sub- Saharan Africa. The taxonomy of the Motacillidae has been contentious, with variable numbers of genera, species and subspecies proposed and some studies suggesting greater taxonomic diversity than what is currently (five genera and 67 species) recognised. Using one nuclear (Mb) and two mitochondrial (cyt b and CO1) gene regions amplified from DNA extracted from contemporary and museum specimens, we investigated the taxonomic status of 56 of the currently recognised motacillid species and present the most taxonomically complete and expanded phylogeny of this family to date. Our results suggest that the family comprises six clades broadly reflecting continental distributions: sub-Saharan Africa (two clades), the New World (one clade), Palaearctic (one clade), a widespread large-bodied Anthus clade, and a sixth widespread genus, Motacilla. -

SOUTH AFRICA: LAND of the ZULU 26Th October – 5Th November 2015

Tropical Birding Trip Report South Africa: October/November 2015 A Tropical Birding CUSTOM tour SOUTH AFRICA: LAND OF THE ZULU th th 26 October – 5 November 2015 Drakensberg Siskin is a small, attractive, saffron-dusted endemic that is quite common on our day trip up the Sani Pass Tour Leader: Lisle Gwynn All photos in this report were taken by Lisle Gwynn. Species pictured are highlighted RED. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-0514 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report South Africa: October/November 2015 INTRODUCTION The beauty of Tropical Birding custom tours is that people with limited time but who still want to experience somewhere as mind-blowing and birdy as South Africa can explore the parts of the country that interest them most, in a short time frame. South Africa is, without doubt, one of the most diverse countries on the planet. Nowhere else can you go from seeing Wandering Albatross and penguins to seeing Leopards and Elephants in a matter of hours, and with countless world-class national parks and reserves the options were endless when it came to planning an itinerary. Winding its way through the lush, leafy, dry, dusty, wet and swampy oxymoronic province of KwaZulu-Natal (herein known as KZN), this short tour followed much the same route as the extension of our South Africa set departure tour, albeit in reverse, with an additional focus on seeing birds at the very edge of their range in semi-Karoo and dry semi-Kalahari habitats to add maximum diversity. KwaZulu-Natal is an oft-underrated birding route within South Africa, featuring a wide range of habitats and an astonishing diversity of birds. -

Second State Of

Second State of the Environment 2002 Report Lesotho Lesotho Second State of the Environment Report 2002 Authors: Chaba Mokuku, Tsepo Lepono, Motlatsi Mokhothu Thabo Khasipe and Tsepo Mokuku Reviewer: Motebang Emmanuel Pomela Published by National Environment Secretariat Ministry of Tourism, Environment & Culture Government of Lesotho P.O. Box 10993, Maseru 100, Lesotho ISBN 99911-632-6-0 This document should be cited as Lesotho Second State of the Environment Report for 2002. Copyright © 2004 National Environment Secretariat. All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. Design and production by Pheko Mathibeli, graphic designer, media practitioner & chartered public relations practitioner Set in Century Gothic, Premium True Type and Optima Lesotho, 2002 3 Contents List of Tables 8 Industrial Structure: Sectoral Composition 34 List of Figures 9 Industrial Structure: Growth Rates 36 List of Plates 10 Population Growth 37 Acknowledgements 11 Rural to Urban Migration 37 Foreword 12 Incidence of Poverty 38 Executive Summary 14 Inappropriate Technologies 38 State and impacts: trends 38 Introduction 24 Human Development Trends 38 Poverty and Income Distribution 44 Socio-Economic and Cultural Environment. 26 Agriculture and Food Security 45 People, Economy and Development Ensuring Long and Healthy Lives 46 Socio-Economic Dimension 26 Ensuring -

South Africa Comprehensive I 11Th – 30Th January 2019 (20 Days) Trip Report

South Africa Comprehensive I 11th – 30th January 2019 (20 days) Trip Report Yellow-billed Hornbill by Peter Day Trip report compiled by Tour Leader: Doug McCulloch Rockjumper Birding Tours View more tours to South Africa Trip Report – RBT South Africa - Comprehensive I 2019 2 Tour Summary This was a very successful and enjoyable tour. Starting in the economic hub of Johannesburg, we spent the next three weeks exploring the wonderful diversity of this beautiful country. The Kruger National Park was great fun, and we were blessed to not only see the famous “Big 5” plus the rare African Wild Dog, but to also have great views of these animals. Memorable sightings were a large male Leopard with its kill hoisted into a tree, and two White Rhino bulls in pugilistic mood. The endangered mesic grasslands around Wakkerstroom produced a wealth of endemics, including Blue Korhaan, Botha’s and Rudd’s Larks, Yellow-breasted Pipit, Southern Bald Ibis and Meerkat. Our further exploration of eastern South Africa yielded such highlights as Blue Crane, Ground Woodpecker, Pink-throated and Green Twinspots, Drakensberg Rockjumper, Spotted and Orange Ground Thrushes, a rare Golden Pipit, Gorgeous Bushshrike, and Livingstone’s and Knysna Turacos. From Sani Pass, we winged our way to the Fairest Cape and its very own plant kingdom. This extension did not disappoint, with specials such as Cape Rockjumper, Cinnamon-breasted, Rufous-eared, Victorin’s and Namaqua Warblers, Verreaux’s Eagle, Karoo Eremomela, Cape Siskin and Protea Canary. We ended with a great count of 488 bird species, including most of the endemic targets, and made some wonderful memories to cherish! ___________________________________________________________________________________ Top 10 list: 1. -

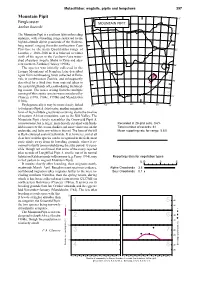

Mountain Pipit

Motacillidae: wagtails, pipits and longclaws 397 Mountain Pipit 14˚ Bergkoester MOUNTAIN PIPIT Anthus hoeschi 1 5 The Mountain Pipit is a southern African breeding 18˚ endemic, with a breeding range restricted to the highest-altitude alpine grasslands of the Drakens- berg massif, ranging from the northeastern Cape Province to the main Quathlamba range of 22˚ Lesotho, c. 1800–3000 m. It is believed to winter 6 north of the region in the Zambezi–Zaire water- 2 shed of eastern Angola, Shaba in Zaire and adja- cent northern Zambia (Clancey 1990b). 26˚ The species was initially collected in the Erongo Mountains of Namibia, later described again from nonbreeding birds collected at Balo- vale in northwestern Zambia, and subsequently 3 7 described for a third time from material taken in 30˚ the eastern highlands of Lesotho during the breed- ing season. The issues arising from the multiple naming of this cryptic species were considered by 4 8 Clancey (1978, 1984c, 1990b) and Mendelsohn 34˚ (1984). 18˚ 22˚ 26˚ Phylogenetically it may be most closely linked 10˚ 14˚ 30˚ 34˚ to Jackson’s Pipit A. latistriatus, another enigmatic form of high-altitude grasslands occurring above the treeline of western African mountains, east to the Rift Valley. The Mountain Pipit closely resembles the Grassveld Pipit A. cinnamomeus, but is larger, more heavily streaked with black- Recorded in 28 grid cells, 0.6% ish brown over the crown, duskier and more vinaceous on the Total number of records: 61 underside, and lacks any white in the tail. The base of the bill Mean reporting rate for range: 5.6% is flesh-coloured and not yellowish. -

Biodiversity Observations

Biodiversity Observations http://bo.adu.org.za An electronic journal published by the Animal Demography Unit at the University of Cape Town The scope of Biodiversity Observations consists of papers describing observations about biodiversity in general, including animals, plants, algae and fungi. This includes observations of behaviour, breeding and flowering patterns, distributions and range extensions, foraging, food, movement, measurements, habitat and colouration/plumage variations. Biotic interactions such as pollination, fruit dispersal, herbivory and predation fall within the scope, as well as the use of indigenous and exotic species by humans. Observations of naturalised plants and animals will also be considered. Biodiversity Observations will also publish a variety of other interesting or relevant biodiversity material: reports of projects and conferences, annotated checklists for a site or region, specialist bibliographies, book reviews and any other appropriate material. Further details and guidelines to authors are on this website. Lead Editor: Arnold van der Westhuizen – Paper Editor: Les G Underhill CHECKLIST AND ANALYSIS OF THE BIRDS OF NAMIBIA AS AT 31 JANUARY 2016 CJ Brown, JM Mendelsohn, N Thomson & M Boorman Recommended citation format: Brown CJ, Mendelsohn JM, Thomson N, Boorman M 2017. Checklist and analysis of the birds of Namibia as at 31 January 2016. Biodiversity Observations 8.20: 1–153 URL: http://bo.adu.org.za/content.php?id=315 Published online: 22 April 2017 – ISSN 2219-0341 – Biodiversity Observations 8.20: -

Pipitsrefs V1.5.Pdf

Introduction I have endeavoured to keep typos, errors, omissions etc in this list to a minimum, however when you find more I would be grateful if you could mail the details during 2018 & 2019 to: [email protected]. Please note that this and other Reference Lists I have compiled are not exhaustive and are best employed in conjunction with other sources. Grateful thanks to Tom Shevlin (http://irishbirds.ie/) and Paul Archer for the cover images. Joe Hobbs Index The general order of species follows the International Ornithologists' Union World Bird List (Gill, F. & Donsker, D. (eds.) 2018. IOC World Bird List. Available from: http://www.worldbirdnames.org/ [version 8.1 accessed January 2018]). Note¹ - For completeness, the list continues to include both Long-tailed Pipit Anthus longicaudatus and Kimberley Pipit A. pseudosimilis despite their suspect provenance (see Davies, G.B.P. & Peacock, D.S. 2014. Reassessment of plumage characters and morphometrics of Anthus longicaudatus Liversidge, 1996 and Anthus pseudosimilis Liversidge and Voelker, 2002 (Aves: Motacillidae). Annals of the Ditsong National Museum of Natural History 4: 187-206). Version Version 1.5 (February 2018). Cover Main image: Tawny Pipit. Great Saltee Island, Co. Wexford, Ireland. 11th May 2008. Picture by Tom Shevlin. Vignette: Buff-bellied Pipit. Clonea, Ballinclamper, Co. Waterford. 22nd November 2011. Picture by Paul Archer. Species Page No. African Rock Pipit [Anthus crenatus] 30 Alpine Pipit [Anthus gutturalis] 32 Australian Pipit [Anthus australis] 6 Berthelot’s Pipit -

Vertebrate Distributions Indicate a Greater Maputaland-Pondoland-Albany Region of Endemism

Page 1 of 15 Research Article Vertebrate distributions indicate a greater Maputaland-Pondoland-Albany region of endemism Authors: The Maputaland-Pondoland-Albany (MPA) biodiversity hotspot (-274 316 km^) was primarily Sandun J. Perera' recogni.sed based on its high plant endemism. Here we present the results of a qualitative Dayani Ratnayake-Perera' 5erban Prochej' biogeographical study of the endemic vertebrate fauna of south-eastern Africa, in an exercise that (1) refines the delimitation of the MPA hotspot, (2) defines zoogeographical units and (3) Affiliation: idenfifies areas of vertebrate endemism. Inifially we listed 62 vertebrate species endemic and 'School of Environmental 60 near endemic to the MPA hotspot, updating previous checklists. Then the distribufions of Sciences, University of 495 vertebrate taxa endemic to south-eastern Africa were reviewed and 23 endemic vertebrate KwaZulu-Natal, Westviile campus, Durban, distributions (EVDs: distribution ranges congruent across several endemic vertebrate taxa) South Africa were recognised, amongst which the most frequently encountered were located in the Eastern Escarpment, central KwaZulu-Natal, Drakensberg and Maputaland. The geographical Correspondence to: patterns illustrated by the EVDs suggest that an expansion of the hotspot to incorporate Sandun Perera secfions of the Great Escarpment from the Amatola-Winterberg-Sneeuberg Mountains Email: through the Drakensberg to the Soutpansberg would be justified. This redefinifion gives rise sandun.perera (Bigmail.com to a Greater Maputaland-Pondoland-Albany (GMPA) region of vertebrate endemism adding 135% more endemics with an increase of only 73% in surface area to the MPA hotspot. The Postal address: School of Environmental GMPA region has a more natural boundary in terms of EVDs as well as vegetafion units. -

The Mountain Pipit Anthus Hoeschi: Museum Specimens Revisited

28 MOUNTAIN PIPIT Durban Natural Science Museum Novitates 38 THE MOUNTAIN PIPIT ANTHUS HOESCHI: MUSEUM SPECIMENS REVISITED a.J.F.K. CraIg Department of Zoology & Entomology, Rhodes University, Grahamstown 6140, South Africa email: [email protected] raig, a.J.F.K. 2015. The Mountain pipit Anthus hoeschi: museum specimens revisited. Durban Natural Science Museum Novitates 38: C28-40. The current name for the Mountain Pipit, which breeds in summer in the high Drakensberg of South Africa and Lesotho, is Anthus hoeschi (type specimen from Namibia), with the taxa editus (Lesotho) and lwenarum (Zambia) as synonyms. Critical examination of the museum material on which this decision was based, comparing measurements and plumage characteristics of these taxa, suggests that Anthus editus should be the name used for this breeding population and it should not be lumped with Namibian and Zambian birds. The proposed long-distance migration to the north-west beyond the borders of South Africa is not supported by the available data and it is likely that the Mountain Pipit is a local altitudinal migrant. KEYWORDS: Mountain Pipit, Anthus hoeschi, editus, lwenarum, moult, morphology, taxonomy, museum specimens. INTRODUCTION Voelker (1999a, b) reviewed the phylogeny of the genus Anthus, The Mountain Pipit Anthus hoeschi has been recognised as a species and collected material in South Africa for DNA studies. However, he separate from the Grassveld (now African) Pipit A. cinnamomeus for did not sample tissues from existing museum material. He concluded some 30 years (Clancey 1984). The decision to treat as conspecific that hoeschi, based on two specimens from a locality “90 km N and the taxa A.