Subspeciation in the Pipit Anthus Cinnamomeus Rüppell of the Afrotropics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesotho Fourth National Report on Implementation of Convention on Biological Diversity

Lesotho Fourth National Report On Implementation of Convention on Biological Diversity December 2009 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ADB African Development Bank CBD Convention on Biological Diversity CCF Community Conservation Forum CITES Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species CMBSL Conserving Mountain Biodiversity in Southern Lesotho COP Conference of Parties CPA Cattle Post Areas DANCED Danish Cooperation for Environment and Development DDT Di-nitro Di-phenyl Trichloroethane EA Environmental Assessment EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EMP Environmental Management Plan ERMA Environmental Resources Management Area EMPR Environmental Management for Poverty Reduction EPAP Environmental Policy and Action Plan EU Environmental Unit (s) GA Grazing Associations GCM Global Circulation Model GEF Global Environment Facility GMO Genetically Modified Organism (s) HIV/AIDS Human Immuno Virus/Acquired Immuno-Deficiency Syndrome HNRRIEP Highlands Natural Resources and Rural Income Enhancement Project IGP Income Generation Project (s) IUCN International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources LHDA Lesotho Highlands Development Authority LMO Living Modified Organism (s) Masl Meters above sea level MDTP Maloti-Drakensberg Transfrontier Conservation and Development Project MEAs Multi-lateral Environmental Agreements MOU Memorandum Of Understanding MRA Managed Resource Area NAP National Action Plan NBF National Biosafety Framework NBSAP National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan NEAP National Environmental Action -

Zambia and Namibia a Tropical Birding Custom Trip

Zambia and Namibia A Tropical Birding Custom Trip October 31 to November 17, 2009 Guide: Ken Behrens All photos by Ken Behrens unless noted otherwise All Namibia and most Zambia photos taken during this trip INTRODUCTION Southern Africa offers a tremendous diversity of habitats, birds, and mammals, and this tour experienced nearly the full gamut: from the mushitus of northern Zambia, with their affinity to the great Congolese rainforests, to the bare dunes and gravel plains of the Namib desert. This was a custom tour with dual foci: a specific list of avian targets for Howard and good general mammal viewing for Diane. On both fronts, we were highly successful. We amassed a list of 479 birds, including a high proportion of Howard’s targets. Of course, this list could have been much higher, had the focus been general birding rather than target birding. ‘Mammaling’ was also fantastic, with 51 species seen. We enjoyed an incredible experience of one of the greatest gatherings of mammals on earth: a roost of straw-coloured fruit bats in Zambia that includes millions of individuals. In Namibia’s Etosha National Park, it was the end of the dry season, and any place with water had mammals in incredible concentrations. The undoubted highlight there was seeing lions 5 different times, including a pride with a freshly killed rhino and a female that chased and killed a southern oryx, then shared it with her pride. In Zambia, much of our birding was in miombo, a type of broadleaf woodland that occurs in a broad belt across south / central Africa, and that has a large set of specialty birds. -

Miombo Ecoregion Vision Report

MIOMBO ECOREGION VISION REPORT Jonathan Timberlake & Emmanuel Chidumayo December 2001 (published 2011) Occasional Publications in Biodiversity No. 20 WWF - SARPO MIOMBO ECOREGION VISION REPORT 2001 (revised August 2011) by Jonathan Timberlake & Emmanuel Chidumayo Occasional Publications in Biodiversity No. 20 Biodiversity Foundation for Africa P.O. Box FM730, Famona, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe PREFACE The Miombo Ecoregion Vision Report was commissioned in 2001 by the Southern Africa Regional Programme Office of the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF SARPO). It represented the culmination of an ecoregion reconnaissance process led by Bruce Byers (see Byers 2001a, 2001b), followed by an ecoregion-scale mapping process of taxa and areas of interest or importance for various ecological and bio-physical parameters. The report was then used as a basis for more detailed discussions during a series of national workshops held across the region in the early part of 2002. The main purpose of the reconnaissance and visioning process was to initially outline the bio-physical extent and properties of the so-called Miombo Ecoregion (in practice, a collection of smaller previously described ecoregions), to identify the main areas of potential conservation interest and to identify appropriate activities and areas for conservation action. The outline and some features of the Miombo Ecoregion (later termed the Miombo– Mopane Ecoregion by Conservation International, or the Miombo–Mopane Woodlands and Grasslands) are often mentioned (e.g. Burgess et al. 2004). However, apart from two booklets (WWF SARPO 2001, 2003), few details or justifications are publically available, although a modified outline can be found in Frost, Timberlake & Chidumayo (2002). Over the years numerous requests have been made to use and refer to the original document and maps, which had only very restricted distribution. -

The Maloti Drakensberg Experience See Travel Map Inside This Flap❯❯❯

exploring the maloti drakensberg route the maloti drakensberg experience see travel map inside this flap❯❯❯ the maloti drakensberg experience the maloti drakensberg experience …the person who practices ecotourism has the opportunity of immersing him or herself in nature in a way that most people cannot enjoy in their routine, urban existences. This person “will eventually acquire a consciousness and knowledge of the natural environment, together with its cultural aspects, that will convert him or her into somebody keenly involved in conservation issues… héctor ceballos-lascuráin internationally renowned ecotourism expert” travel tips for the maloti drakensberg region Eastern Cape Tourism Board +27 (0)43 701 9600 www.ectb.co.za, [email protected] lesotho south africa Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife currency Maloti (M), divided into 100 lisente (cents), have currency The Rand (R) is divided into 100 cents. Most +27 (0)33 845 1999 an equivalent value to South African rand which are used traveller’s cheques are accepted at banks and at some shops www.kznwildlife.com; [email protected] interchangeably in Lesotho. Note that Maloti are not accepted and hotels. Major credit cards are accepted in most towns. Free State Tourism Authority in South Africa in place of rand. banks All towns will have at least one bank. Open Mon to Fri: +27 (0)51 411 4300 Traveller’s cheques and major credit cards are generally 09h00–15h30, Sat: 09h00–11h00. Autobanks (or ATMs) are www.dteea.fs.gov.za accepted in Maseru. All foreign currency exchange should be found in most towns and operate on a 24-hour basis. -

South Africa Mega Birding III 5Th to 27Th October 2019 (23 Days) Trip Report

South Africa Mega Birding III 5th to 27th October 2019 (23 days) Trip Report The near-endemic Gorgeous Bushshrike by Daniel Keith Danckwerts Tour leader: Daniel Keith Danckwerts Trip Report – RBT South Africa – Mega Birding III 2019 2 Tour Summary South Africa supports the highest number of endemic species of any African country and is therefore of obvious appeal to birders. This South Africa mega tour covered virtually the entire country in little over a month – amounting to an estimated 10 000km – and targeted every single endemic and near-endemic species! We were successful in finding virtually all of the targets and some of our highlights included a pair of mythical Hottentot Buttonquails, the critically endangered Rudd’s Lark, both Cape, and Drakensburg Rockjumpers, Orange-breasted Sunbird, Pink-throated Twinspot, Southern Tchagra, the scarce Knysna Woodpecker, both Northern and Southern Black Korhaans, and Bush Blackcap. We additionally enjoyed better-than-ever sightings of the tricky Barratt’s Warbler, aptly named Gorgeous Bushshrike, Crested Guineafowl, and Eastern Nicator to just name a few. Any trip to South Africa would be incomplete without mammals and our tally of 60 species included such difficult animals as the Aardvark, Aardwolf, Southern African Hedgehog, Bat-eared Fox, Smith’s Red Rock Hare and both Sable and Roan Antelopes. This really was a trip like no other! ____________________________________________________________________________________ Tour in Detail Our first full day of the tour began with a short walk through the gardens of our quaint guesthouse in Johannesburg. Here we enjoyed sightings of the delightful Red-headed Finch, small numbers of Southern Red Bishops including several males that were busy moulting into their summer breeding plumage, the near-endemic Karoo Thrush, Cape White-eye, Grey-headed Gull, Hadada Ibis, Southern Masked Weaver, Speckled Mousebird, African Palm Swift and the Laughing, Ring-necked and Red-eyed Doves. -

Longbilled Pipit Ground to Feed on Incapacitated Insects

382 Motacillidae: wagtails, pipits and longclaws Habitat: It generally frequents slopes in rela- tively arid and eroded, broken veld, often steppe- like with erosion scars, stones and outcrop rock interspersed with grass clumps and low scrub. It is often among low trees and light woodland on stony ground, but will visit adjacent well-grazed areas and bare or burnt ground liberally scattered with the droppings of stock. It is sparse at the coast with populations most numerous c. 500– 2500 m, penetrating some way into desert in the western parts of the range, e.g. the lower Orange River and along the inland edge of the Namib. Movements: It is more sedentary than other sympatric pipits of comparable size, and not sub- ject to the well-defined seasonal altitudinal shifts seen in some other species. This is reflected in the models. Breeding: Atlas breeding records indicate a spring/summer season with a September–Decem- ber peak, which agrees with published informa- tion (Dean 1971; Irwin 1981; Tarboton et al. 1987b; Maclean 1993b). Interspecific relationships: The Wood Pipit is this species’ counterpart in the Brachystegia woodland of much of southcentral Africa. It is believed to be allopatric with the Wood Pipit (Clancey 1988b), but further research is needed, particularly in the eastern highlands in Zimbabwe where the Wood Pipit occurs in rocky grassland habitat (Irwin 1981) normally typical of Long- billed Pipit. This pipit frequently consorts with other pipits, longclaws and rockthrushes on recently burnt Longbilled Pipit ground to feed on incapacitated insects. Nicholsonse Koester Historical distribution and conservation: As it largely inhabits land unsuitable for agriculture, it has probably Anthus similis suffered little from habitat loss and degradation. -

Multi-Locus Phylogeny of African Pipits and Longclaws (Aves: Motacillidae) Highlights Taxonomic Inconsistencies

Running head: African pipit and longclaw taxonomy Multi-locus phylogeny of African pipits and longclaws (Aves: Motacillidae) highlights taxonomic inconsistencies DARREN W. PIETERSEN,1* ANDREW E. MCKECHNIE,1,2 RAYMOND JANSEN,3 IAN T. LITTLE4 AND ARMANDA D.S. BASTOS5 1DST-NRF Centre of Excellence at the Percy FitzPatrick Institute, Department of Zoology and Entomology, University of Pretoria, Hatfield, South Africa 2South African Research Chair in Conservation Physiology, National Zoological Garden, South African National Biodiversity Institute, P.O. Box 754, Pretoria 0001, South Africa 3Department of Environmental, Water and Earth Sciences, Tshwane University of Technology, Pretoria, South Africa 4Endangered Wildlife Trust, Johannesburg, South Africa 5Department of Zoology and Entomology, University of Pretoria, Hatfield, South Africa *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] 1 Abstract The globally distributed avian family Motacillidae consists of 5–7 genera (Anthus, Dendronanthus, Tmetothylacus, Macronyx and Motacilla, and depending on the taxonomy followed, Amaurocichla and Madanga) and 66–68 recognised species, of which 32 species in four genera occur in sub- Saharan Africa. The taxonomy of the Motacillidae has been contentious, with variable numbers of genera, species and subspecies proposed and some studies suggesting greater taxonomic diversity than what is currently (five genera and 67 species) recognised. Using one nuclear (Mb) and two mitochondrial (cyt b and CO1) gene regions amplified from DNA extracted from contemporary and museum specimens, we investigated the taxonomic status of 56 of the currently recognised motacillid species and present the most taxonomically complete and expanded phylogeny of this family to date. Our results suggest that the family comprises six clades broadly reflecting continental distributions: sub-Saharan Africa (two clades), the New World (one clade), Palaearctic (one clade), a widespread large-bodied Anthus clade, and a sixth widespread genus, Motacilla. -

Ecology of Passerine Birds Wintering at Utah Lake

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1951-06-01 Ecology of Passerine birds wintering at Utah Lake Joseph R. Murphy Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Murphy, Joseph R., "Ecology of Passerine birds wintering at Utah Lake" (1951). Theses and Dissertations. 7834. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/7834 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. j!) /,_ ., ) Cvl <::::-.. , rOL ,/I . ,-,:/ _··. , Mi7 \q_5\ ECOLOGYOF PASSERINEBIRDS WINTERINGAT UTAHLAKE A Thesis submitted to the Department of Zoology and Entomology ot Brigham Young University In partial fulfillment or the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Joseph R. Murphy June 19,1 ..-: '" Thia thesis by Joseph a. KurphJ 11 accepted 1n its present form by the Special Thesis Committee as satlsty1n1 the thesis requirements tor the degree ot Master of Arts. signed 11 II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this thesis is due in a large part to the aid and assistance which have been rendered to the writer by several individuals and organizations. Appreciation is especially extended to Dr. c. Lynn Hayward, the writer's Special Thesis Committee chairman, and to Dr. B. F. Harrison, committee member. Dr. Hayward has given freely of his time and knowledge in guiding the thesis work; Dr. Harrison has made many valuable suggestions and helped greatly in the identification of plants occurring in the study area. -

SOUTH AFRICA: LAND of the ZULU 26Th October – 5Th November 2015

Tropical Birding Trip Report South Africa: October/November 2015 A Tropical Birding CUSTOM tour SOUTH AFRICA: LAND OF THE ZULU th th 26 October – 5 November 2015 Drakensberg Siskin is a small, attractive, saffron-dusted endemic that is quite common on our day trip up the Sani Pass Tour Leader: Lisle Gwynn All photos in this report were taken by Lisle Gwynn. Species pictured are highlighted RED. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-0514 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report South Africa: October/November 2015 INTRODUCTION The beauty of Tropical Birding custom tours is that people with limited time but who still want to experience somewhere as mind-blowing and birdy as South Africa can explore the parts of the country that interest them most, in a short time frame. South Africa is, without doubt, one of the most diverse countries on the planet. Nowhere else can you go from seeing Wandering Albatross and penguins to seeing Leopards and Elephants in a matter of hours, and with countless world-class national parks and reserves the options were endless when it came to planning an itinerary. Winding its way through the lush, leafy, dry, dusty, wet and swampy oxymoronic province of KwaZulu-Natal (herein known as KZN), this short tour followed much the same route as the extension of our South Africa set departure tour, albeit in reverse, with an additional focus on seeing birds at the very edge of their range in semi-Karoo and dry semi-Kalahari habitats to add maximum diversity. KwaZulu-Natal is an oft-underrated birding route within South Africa, featuring a wide range of habitats and an astonishing diversity of birds. -

Second State Of

Second State of the Environment 2002 Report Lesotho Lesotho Second State of the Environment Report 2002 Authors: Chaba Mokuku, Tsepo Lepono, Motlatsi Mokhothu Thabo Khasipe and Tsepo Mokuku Reviewer: Motebang Emmanuel Pomela Published by National Environment Secretariat Ministry of Tourism, Environment & Culture Government of Lesotho P.O. Box 10993, Maseru 100, Lesotho ISBN 99911-632-6-0 This document should be cited as Lesotho Second State of the Environment Report for 2002. Copyright © 2004 National Environment Secretariat. All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. Design and production by Pheko Mathibeli, graphic designer, media practitioner & chartered public relations practitioner Set in Century Gothic, Premium True Type and Optima Lesotho, 2002 3 Contents List of Tables 8 Industrial Structure: Sectoral Composition 34 List of Figures 9 Industrial Structure: Growth Rates 36 List of Plates 10 Population Growth 37 Acknowledgements 11 Rural to Urban Migration 37 Foreword 12 Incidence of Poverty 38 Executive Summary 14 Inappropriate Technologies 38 State and impacts: trends 38 Introduction 24 Human Development Trends 38 Poverty and Income Distribution 44 Socio-Economic and Cultural Environment. 26 Agriculture and Food Security 45 People, Economy and Development Ensuring Long and Healthy Lives 46 Socio-Economic Dimension 26 Ensuring -

South Africa Comprehensive I 11Th – 30Th January 2019 (20 Days) Trip Report

South Africa Comprehensive I 11th – 30th January 2019 (20 days) Trip Report Yellow-billed Hornbill by Peter Day Trip report compiled by Tour Leader: Doug McCulloch Rockjumper Birding Tours View more tours to South Africa Trip Report – RBT South Africa - Comprehensive I 2019 2 Tour Summary This was a very successful and enjoyable tour. Starting in the economic hub of Johannesburg, we spent the next three weeks exploring the wonderful diversity of this beautiful country. The Kruger National Park was great fun, and we were blessed to not only see the famous “Big 5” plus the rare African Wild Dog, but to also have great views of these animals. Memorable sightings were a large male Leopard with its kill hoisted into a tree, and two White Rhino bulls in pugilistic mood. The endangered mesic grasslands around Wakkerstroom produced a wealth of endemics, including Blue Korhaan, Botha’s and Rudd’s Larks, Yellow-breasted Pipit, Southern Bald Ibis and Meerkat. Our further exploration of eastern South Africa yielded such highlights as Blue Crane, Ground Woodpecker, Pink-throated and Green Twinspots, Drakensberg Rockjumper, Spotted and Orange Ground Thrushes, a rare Golden Pipit, Gorgeous Bushshrike, and Livingstone’s and Knysna Turacos. From Sani Pass, we winged our way to the Fairest Cape and its very own plant kingdom. This extension did not disappoint, with specials such as Cape Rockjumper, Cinnamon-breasted, Rufous-eared, Victorin’s and Namaqua Warblers, Verreaux’s Eagle, Karoo Eremomela, Cape Siskin and Protea Canary. We ended with a great count of 488 bird species, including most of the endemic targets, and made some wonderful memories to cherish! ___________________________________________________________________________________ Top 10 list: 1. -

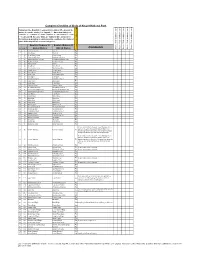

Kruger Comprehensive

Complete Checklist of birds of Kruger National Park Status key: R = Resident; S = present in summer; W = present in winter; E = erratic visitor; V = Vagrant; ? - Uncertain status; n = nomadic; c = common; f = fairly common; u = uncommon; r = rare; l = localised. NB. Because birds are highly mobile and prone to fluctuations depending on environmental conditions, the status of some birds may fall into several categories English (Roberts 7) English (Roberts 6) Comments Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps # Rob # Global Names Old SA Names Rough Status of Bird in KNP 1 1 Common Ostrich Ostrich Ru 2 8 Little Grebe Dabchick Ru 3 49 Great White Pelican White Pelican Eu 4 50 Pinkbacked Pelican Pinkbacked Pelican Er 5 55 Whitebreasted Cormorant Whitebreasted Cormorant Ru 6 58 Reed Cormorant Reed Cormorant Rc 7 60 African Darter Darter Rc 8 62 Grey Heron Grey Heron Rc 9 63 Blackheaded Heron Blackheaded Heron Ru 10 64 Goliath Heron Goliath Heron Rf 11 65 Purple Heron Purple Heron Ru 12 66 Great Egret Great White Egret Rc 13 67 Little Egret Little Egret Rf 14 68 Yellowbilled Egret Yellowbilled Egret Er 15 69 Black Heron Black Egret Er 16 71 Cattle Egret Cattle Egret Ru 17 72 Squacco Heron Squacco Heron Ru 18 74 Greenbacked Heron Greenbacked Heron Rc 19 76 Blackcrowned Night-Heron Blackcrowned Night Heron Ru 20 77 Whitebacked Night-Heron Whitebacked Night Heron Ru 21 78 Little Bittern Little Bittern Eu 22 79 Dwarf Bittern Dwarf Bittern Sr 23 81 Hamerkop