SFRA Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Microfilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the mateiial submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

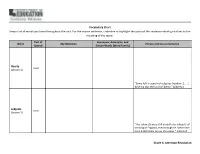

Vocabulary Chart Keep a List of Words You Learn Throughout the Unit. For

Vocabulary Chart Keep a list of words you learn throughout the unit. For the source sentence, underline or highlight the parts of the sentence which give clues to the meaning of the word. Part of Synonyms, Antonyms, and Word My Definition Picture and Source Sentence Speech Similar Words (Word Family) liberty noun (Lesson 1) “Some left in search of religious freedom. [. .] America was the land of liberty.” (Liberty!) subjects noun (Lesson 1) “The colonists were still proud to be subjects of the king of England, even though he ruled them from 3,000 miles across the ocean.” (Liberty!) Grade 4: American Revolution Part of Synonyms, Antonyms, and Word My Definition Picture and Source Sentence Speech Similar Words (Word Family) opportunity noun (Lesson 1) “But in America, if you worked hard, you might become one of the richest people in the land. [. .] they were very glad to live in the new and wonderful land of opportunity‐‐ America.” (Liberty!) ally noun (Lesson 1) “[The English settlers] had a powerful ally‐‐England. They called England the ‘Mother Country.’ [. .] Now that her children were in danger, the Mother Country sent soldiers to help the settlers’ own troops defend the colonies against their enemies.” (Liberty!) Grade 4: American Revolution Part of Synonyms, Antonyms, and Word My Definition Picture and Source Sentence Speech Similar Words (Word Family) possession noun (Lesson 1) “France lost almost all her possessions in North America. Britain got Canada and most of the French lands east of the Mississippi.” (Liberty!) declaration noun (Lesson 3) “The Declaration of Independence, which was signed by members of the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, showed that the colonies wanted to be free.” (...If You Lived at the Time...) Grade 4: American Revolution Part of Synonyms, Antonyms, and Word My Definition Picture and Source Sentence Speech Similar Words (Word Family) interested verb (Lesson 3) “Each colony was interested only in its local problems. -

Cyclopaedia 15 – Alternate History Overview

Cyclopaedia 15 – Alternate History By T.R. Knight (InnRoads Ministries * Article Series) Overview dimensions, or technological changes to explore these historical changes. Steampunk, Alternate History brings up many thoughts dieselpunk, and time/dimensional travel and feelings. To historical purists, this genre stories are good examples of this subcategory of fiction can look like historical revisionism. of Alternate History. Alternate History rides a Speculative fiction fans view these as “What fine line between Historical Fiction and If” scenarios that challenge us to think Science Fiction at this point. outside historical norms to how the world could be different today. Within the science Whatever type of Alternate History you fiction genre, alternate history can take on enjoy, each challenges your preconceived many sub-genres such as time travel, understandings and feelings for a time period alternate timelines, steampunk, and in history, perhaps offering you new dieselpunk. All agree that Alternate History perspectives on the people and events speculates to altered outcomes of key events involved. in history. These minor or major alterations Most common types of have ripple effects, creating different social, political, cultural, and/or scientific levels in Alternate History? the world. Alternate History has so many sub-genres Alternate History takes some queues from associated with it. Each one has its own Science Fiction as a genre. Just like Science unique alteration of history, many of which Fiction, Alternate History can be organized are considered genres or themes unto into two sub-categories that are “Hard” and themselves. “Soft” like Science Fiction. 80s Cold War invasion of United “Hard” Alternate History could be viewed as States stories and themes that stay as true to actual Axis victory in World War II history as possible with just one or two single Confederate victory in American changes that change the outcome, such as Civil War the Confederate Army winning the Civil War Dieselpunk or the Axis winning World War 2. -

Science Fiction List Literature 1

Science Fiction List Literature 1. “The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall,” Edgar Allan Poe (1835, US, short story) 2. Looking Backward, Edward Bellamy (1888, US, novel) 3. A Princess of Mars, Edgar Rice Burroughs (1912, US, novel) 4. Herland, Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1915, US, novel) 5. “The Comet,” W.E.B. Du Bois (1920, US, short story) 6. Fahrenheit 451, Ray Bradbury (1951, US, novel) 7. Limbo, Bernard Wolfe (1952, US, novel) 8. The Stars My Destination, Alfred Bester (1956, US, novel) 9. Venus Plus X, Theodore Sturgeon (1960, US, novel) 10. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, Philip K. Dick (1968, US, novel) 11. The Left Hand of Darkness, Ursula K. Le Guin (1969, US, novel) 12. The Female Man, Joanna Russ (1975, US, novel) 13. “The Screwfly Solution,” “The Girl Who Was Plugged In,” “The Women Men Don’t See,” “Houston, Houston Do You Read?”, James Tiptree Jr./Alice Sheldon (1977, 1973, 1973, 1976, US, novelettes, novella) 14. Native Tongue, Suzette Haden Elgin (1984, US, novel) 15. Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand, Samuel R. Delany (1984, US, novel) 16. Neuromancer, William Gibson (1984, US-Canada, novel) 17. The Handmaid’s Tale, Margaret Atwood (1985, Canada, novel) 18. The Gilda Stories, Jewelle L. Gómez (1991, US, novel; extended edition 2016) 19. Dawn, Octavia E. Butler (1987, US, novel); Parable of the Sower, Butler (1993, US, novel); Bloodchild and Other Stories, Butler (1995, US, short stories; extended edition 2005) 20. Red Spider, White Web, Misha Nogha/Misha (1990, US, novel) 21. The Rag Doll Plagues, Alejandro Morales (1991, US, novel) 22. -

Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: a Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Summer 8-7-2012 Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant James H. Shimkus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Shimkus, James H., "Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/95 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING SPECULATIVE FICTION IN COLLEGE: A PEDAGOGY FOR MAKING ENGLISH STUDIES RELEVANT by JAMES HAMMOND SHIMKUS Under the Direction of Dr. Elizabeth Burmester ABSTRACT Speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, and horror) has steadily gained popularity both in culture and as a subject for study in college. While many helpful resources on teaching a particular genre or teaching particular texts within a genre exist, college teachers who have not previously taught science fiction, fantasy, or horror will benefit from a broader pedagogical overview of speculative fiction, and that is what this resource provides. Teachers who have previously taught speculative fiction may also benefit from the selection of alternative texts presented here. This resource includes an argument for the consideration of more speculative fiction in college English classes, whether in composition, literature, or creative writing, as well as overviews of the main theoretical discussions and definitions of each genre. -

Nicoletti Emma 2014.Pdf

Reading Literature in the Anthropocene: Ecosophy and the Ecologically-Oriented Ethics of Jeff Noon’s Nymphomation and Pollen Emma Nicoletti 10012001 B.A. (Hons), The University of Western Australia, 2005 Dip. Ed., The University of Western Australia, 2006 This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities (English and Cultural Studies) 2014 ii Abstract This thesis examines the science fiction novels Nymphomation and Pollen by Jeff Noon. The reading brings together ideas from the eco-sciences, environmental humanities and ecocriticism in order to analyse the ecological dimensions of these texts. Although Noon’s work has been the subject of academic critique, critical discussions of his oeuvre have overlooked the engagement of Nymphomation and Pollen with ecological issues. This is a gap in the scholarship on Noon’s work that this thesis seeks to rectify. These novels depict landscapes and communities as being degraded because of the influence of information technologies and homogeneous ideologies, making them a productive lens through which to consider and critically respond to some of the environmental and social challenges faced by humanity in an anthropogenic climate. In order to discuss the ecological dimensions of these novels, the thesis advances the notion of an “ecosophical reading practice.” This idea draws on Felix Guattari’s concept of “ecosophy,” and combines it with the notions of “ecological thinking” developed in the work of theorists Timothy Morton, Lorraine Code and Gregory Bateson. While Morton’s work is extensively cited in ecocritical scholarship, with a few exceptions, the work of the other theorists is not. -

Vector 187 Speller Et Al 1996-02

1 8 Vector 7 THE CRITICAL JOURNAL OF THE BSFA £2.25 February 1996 Just Lousy With Information Neal Stephenson Interviewed Stephen Baxter on H.G.Wells’ The Invisible Man Hardback Reviews - page 11 Letters - page 3 Paperback Reviews - page 26 Page 2 Editorial Vector 187 On a New Year’s Day visit to Camden, I discovered that the Penguin bookshop had closed down. I remember this particular shop because it seemed to me to sum up the Contents elements of Camden I disliked: it had a cult book section, and I always felt that if you needed a marketing category to tell you Editorial 2 something was a cult, then you were coming to it for the wrong by Andrew Butler reasons. If it has to be explained, you won’t understand it. But cult books have re-emerged, in a joint Waterstones Frontline Despatches 3 / Observer promotion of sixteen cult books read in 1966 and Letters Edited by Gary Dalkin 1996. Leaving aside the arbitrariness of the thirty year gap, the two lists provide interesting reading as to what is considered Cognititve Mapping 2: Language 4 cult material, and what is left out. In 1966, Beat writing is by Paul Kincaid represented by Kerouac’s On the Road and Burroughs’s seminal (in all senses of the word) The Naked Lunch. Three Just Lousy With Information 5 other books on the list may be loosely considered fantasy: Neal Stephenson interviewed by Tanya Brown Hesse’s Steppenwolf, Kafka’s Metamorphosis and Peake’s The Invisible Man 9 Gormenghast. No Lord of the Rings, and no science fiction: no Dune, no Stranger in a Strange Land, no Sirens of Titan. -

Virtual Catastrophe: the Ecologically-Oriented Ethics of Jeff

Virtual Catastrophe: The Ecologically-Oriented Ethics of Jeff Noon’s Pollen Emma Nicoletti Jeff Noon's “Vurt” novels—Vurt , Pollen , Automated Alice , and Nymphomation—occupy an unusual niche within the science fiction subgenre of cyberpunk. 1 Typically, cyberpunk texts are set in near-future dystopian worlds, which are dominated by advanced virtual technologies and powerful corporations, and against this backdrop the skilled computer hacker uncovers conspiracies (often for financial profit). While Noon’s “Vurt” novels certainly include these broad aspects of cyberpunk, their execution of this “formula” differs from the typical cyberpunk mould. In these novels, the action is restricted to Manchester rather than the more cyberpunk-esque urban sprawl settings of North America or Japan, their featured “vurt” technology has an organic rather than mechanistic basis, 2 and, furthermore, they are about “looking reality in the face” rather than fleeing the messiness of the material world to the sterile safety of cyberspace. 3 For Val Gough, this last peculiarity sees Noon's novels constituting an instance of feminist cyberpunk fiction because “for Noon … the meat world constitutes an ethical challenge and a promise of redemption every bit as important as those of virtual reality or cyberspace.” 4 On the other hand, I see in all three cyberpunk-oddities of Noon's novels the promise of an ecologically-aware cyberpunk fiction: Manchester's history of industrialism and redevelopment as a haven for COLLOQUY text theory critique 23 (2012). © Monash University. www.arts.monash.edu.au/ecps/colloquy/journal/issue023/nicoletti.pdf 32 Emma Nicoletti ░ “yuppie” consumers situate it squarely in the environmentalist discourses on pollution and mass consumerism; 5 the depiction of technology as grounded in material reality acknowledges the dependency of all technology on the earth's resources; and, registering our inability to fully escape our bodies or our world nods to the importance of accepting the existence of a material reality that supports all life. -

Yandros; by Our Records, He Began Subscribing with Issue ?#152, in 1965

Published, by Robert & Juanita Coulson, Route 3, Hartford City, IN 473U8, USA British Agent is Alan Dodd, '77 Stanstead Road, Hoddesdon, Herts., Great Britain Price: US, 750, $ for $3*00, 10 for S5«00 - Britain, 35p, 5 for El.fjO, 10 for E2.5O .. CONTENTS . Ramblings (editorial)- - - ------- _ _ _ _ JWC --------- ----------- ------- _______ _ 2 Rumblings ( " )- -------------------------. - RSC-----------.------------------ --------- ---------------- 4 A Coulumn - - — — _________ Bruce Coulson -------------6 An Advertisement Brought To You - - by Darrell Schweitzer, John Miesel, and ■ . • . Sandra Miesel--------8 Star. Laden Trek To A Black Wormhole - - Thomas Stratton - - - - - ------ --- -11 ; Grumblings (letters) - -- -- -- -- -- — ---------------- 14 Special Book Review - -- -- -- -- - rsc. - - - - - - ----------- - - - 13 Things That Go BumpJ In The Mailbox - - the. readers - — — ________ 18 Golden Minutes (book reviews) - - RSC ________ 20 Strange Fruit (fanzine reviews)-----------RSC -----------------. - ------------------------ ------ 39 ARTWORK . Cover by Fred. Jac.obcic Cover logo by Dave Locke Page 1 - - Joyce Scrivner (-wThe State of Reading Yaidro.; part 2 of a series) "2-------- - JWC Page 9 - - — - Alexis Gilliland «4------ -~- JWC " 10 - - - - - Alexis Gilliland " 6 - - - - - - - - - JWC . "L .14 ------ - Al Sirois " 8 - - - - - Alexis Gilliland ’’ 16 ----- - - Jann Frank "An Advertisement Brought To You" copyright 1980 by the authors Irv Jacobs, P.O. Box 57U, National City, CA 92050, is planning to dispose of his old YANDROs; by our records, he began subscribing with issue ?#152, in 1965. He wants 250 apiece, plus pos tage, and wants to sell them as a lot. NEW ADDRESSES ' Bruce Coulson and Lori Huff, 2454 Indiana Ave., Columbus, OH 43202 Ruth Berman, 2809 Dewey, #120, Norman, OK 73069 (for college year only; she’s teaching Freshman Corrip.) Jim Turner, 9218 8th. Ave. NW, Seattle, WA 98117 Hank Luttrell, 2619 Monroe St., Madison, WI 53711 Lesleigh Luttrell, 51h Stang St. -

SF Tube Talk 24 Frames

Spring 2000 ConNotations Volume 10, Issue 1 The Quarterly Science Fiction, Fantasy & Convention Newszine of the Central Arizona Speculative Fiction Society new existance as a being of light and SF Tube Talk blames Janeway and the Voyager crew for 24 Frames In This Issue pushing her into her current state. Kes Special Features by Lee Whiteside manages to travel back in time three years Movie & Video Reviews and intends to arrange for the Vidians to Beyond 2000 Trekking on to a New Adventure capture Voyager as part of her revenge. Currently in Theatres: by Shane Shellenbarger.....................4 There has been lots of rumors and As with any time travel episode, expect to A.E. Van Vogt Obituary speculation about what the next Star Trek be totally confused and for things to The Road to El Dorado Adam Niswander & Daryl Mallett ....6 series will be and when it will start. Rick pretty much be the same at the end of the From Dreamworks featuring the voices of : News & Reviews Berman and Brannon Braga have been episode. In a likely much more light- Kenneth Brannagh, Kevin Kline, Rosie SF Tube Talk developing the series for Viacom but have hearted episode, currently titled “Live Perez, Edward James Olmos and Armand by Lee Whiteside .................................1 given out little info on what they are Fast and Prosper”, three alien con artists Assante Directed by Eric “Bibo” Peterson ........................................1 working on. Reports early in the year were have assumed the identities of Janeway, and Don Paul. 24 Frames. that Viacom set up some focus groups to Tuvok and Chakotay and have been FYI................................................2 get reaction to several concepts although scamming people all over the place. -

Ad Pages Template

VOLUME 26 | ISSUE 19 | MAY 11-17, 2017 | FREE | 2017 11-17, | MAY 19 ISSUE | 26 VOLUME ARCHULETA ON PUBLIC CLOAK, DAGGER & HEY MISTER, PINK FREUD, CHICHARRA HEALTH AND GIVING BACK JESSAMYN LOVELL CHECK OUT SISTER! AND DEAF POETS PAGE: 7 PAGE: 13 PAGE 24 MAKIN’ OUT IN THE BACK ROW SINCE 1992 SINCE ROW BACK THE IN OUT MAKIN’ PAGE: 16 MAY 11-17, 2017 WEEKLY ALIBI [3] alibi VOLUME 26 | ISSUE 19 | MAY 11-17, 2017 EDITORIAL MANAGING EDITOR/COPY EDITOR: Renee Chavez (ext. 255) [email protected] FILM EDITOR: Devin D. O’Leary (ext. 230) [email protected] MUSIC EDITOR/NEWS EDITOR: August March (ext. 245) [email protected] ARTS/LIT EDITOR: Maggie Grimason (ext. 239) [email protected] CALENDARS EDITOR: Children’s Choice is oering Megan Reneau (ext. 260) [email protected] STAFF WRITER: WEEK-LONG Joshua Lee (ext. 243) [email protected] SOCIAL MEDIA COORDINATOR: SUMMER CAMPS Samantha Carrillo (ext. 223) [email protected] in Music, Science, Puppets, Sports, CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: Cecil Adams, Gustavo Arellano, Robin Babb, Bob eater, Flash Mob, Dance, Film, Brezsny, Carolyn Carlson, Doug Cohen, Desmond Fox, Taylor Grabowsky, Kristi D. Lawrence, Sara MacNeil, Percussion, and Harry Potter! Hosho McCreesh, Geoffrey Plant, Mikee Riggs PRODUCTION EDITORIAL DESIGNER: Valerie Serna (ext.254) [email protected] GRAPHIC DESIGNER: Jesse Philips (ext.240) [email protected] STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER: Eric Williams [email protected] CONTRIBUTING ARTISTS: Max Cannon, Michael Ellis, Jodie Herrera, KAZ, Ryan North, Jen Sorensen Check out: SALES SALES DIRECTOR: Tierna Unruh-Enos (ext. 248) [email protected] childrens-choice.org ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES: Kittie Blackwell (ext.