Negative Impact of an Invasive Small Indian Mongoose Herpestes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecology of the Small Indian Mongoose (Herpestes Auropunctatus) in North America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff U.S. Department of Agriculture: Animal and Publications Plant Health Inspection Service 2018 Ecology of the Small Indian Mongoose (Herpestes auropunctatus) in North America Are R. Berentsen USDA National Wildlife Research Center, [email protected] William C. Pitt Smithsonian Institute Robert T. Sugihara USDA/APHIS/WS/National Wildlife Research Center Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc Part of the Life Sciences Commons Berentsen, Are R.; Pitt, William C.; and Sugihara, Robert T., "Ecology of the Small Indian Mongoose (Herpestes auropunctatus) in North America" (2018). USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff Publications. 2034. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_usdanwrc/2034 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USDA National Wildlife Research Center - Staff Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. U.S. Department of Agriculture U.S. Government Publication Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Wildlife Services Ecology of the Small 12 Indian Mongoose (Herpestes auropunctatus) in North America Are R. Berentsen, William C. Pitt, and Robert T. Sugihara CONTENTS General Ecology and Distribution......................................................................... -

Species Identification of Shed Snake Skins in Taiwan and Adjacent Islands

Zoological Studies 56: 38 (2017) doi:10.6620/ZS.2017.56-38 Open Access Species Identification of Shed Snake Skins in Taiwan and Adjacent Islands Tein-Shun Tsai1,* and Jean-Jay Mao2 1Department of Biological Science and Technology, National Pingtung University of Science and Technology 1 Shuefu Road, Neipu, Pingtung 912, Taiwan 2Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, National Ilan University No.1, Sec. 1, Shennong Rd., Yilan City, Yilan County 260, Taiwan. E-mail: [email protected] (Received 28 August 2017; Accepted 25 November 2017; Published 19 December 2017; Communicated by Jian-Nan Liu) Tein-Shun Tsai and Jean-Jay Mao (2017) Shed snake skins have many applications for humans and other animals, and can provide much useful information to a field survey. When properly prepared and identified, a shed snake skin can be used as an important voucher; the morphological descriptions of the shed skins may be critical for taxonomic research, as well as studies of snake ecology and conservation. However, few convenient/ expeditious methods or techniques to identify shed snake skins in specific areas have been developed. In this study, we collected and examined a total of 1,260 shed skin samples - including 322 samples from neonates/ juveniles and 938 from subadults/adults - from 53 snake species in Taiwan and adjacent islands, and developed the first guide to identify them. To the naked eye or from scanned images, the sheds of almost all species could be identified if most of the shed was collected. The key features that aided in identification included the patterns on the sheds and scale morphology. -

Herpetological Journal FULL PAPER

Volume 27 (April 2017), 201–216 Herpetological Journal FULL PAPER Published by the British Predation of Jamaican rock iguana Cyclura( collei) nests Herpetological Society by the invasive small Asian mongoose (Herpestes auropunctatus) and the conservation value of predator control Rick van Veen & Byron S. Wilson Department of Life Sciences, University of the West Indies, Mona 7, Kingston, Jamaica The introduced small Asian mongoose (Herpestes auropunctatus) has been widely implicated in extirpations and extinctions of island taxa. Recent studies and anecdotal observations suggest that the nests of terrestrial island species are particularly vulnerable to mongoose predation, yet quantitative data have remained scarce, even for species long assumed to be at risk from the mongoose. We monitored nests of the Critically Endangered Jamaican Rock Iguana (Cyclura collei) to determine nest fate, and augmented these observations with motion-activated camera trap images to document the predatory behaviour of the mongoose. Our data provide direct, quantitative evidence of high nest predation pressure attributable to the mongoose, and together with reported high rates of predation on hatchling and juvenile iguanas (also by the mongoose), support the original conclusion that the mongoose was responsible for the apparent lack of recruitment and the aging structure of the small population that was ‘re-discovered’ in 1990. Encouragingly however, our data also demonstrate a significant reduction in nest predation pressure within an experimental mongoose-removal area. Thus, our results indicate that otherwise catastrophic levels of nest loss (at or near 100%) can be ameliorated or even eliminated by removal trapping of the mongoose. We suggest that such targeted control efforts could also prove useful in safeguarding other threatened insular species with reproductive strategies that are notably vulnerable to mongoose predation (e.g., the incubation of eggs on or underground). -

Herpestes Auropunctatus (Small Indian Mongoose)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour Herpestes auropunctatus (Small Indian Mongoose) Family: Herpestidae (Mongooses) Order: Carnivora (Carnivores) Class: Mammalia (Mammals) Fig. 1. Small Indian mongoose, Herpestes auropunctatus. [http://kiwifoto.com/galleries/mammals/small_indian_mongoose/, downloaded 21 September 2012] TRAITS. Herpestes auropunctatus (formerly known as H. javanicus) is native to south Asia and has been introduced to Trinidad and Tobago (and other Caribbean islands) for control of rats and snakes. This animal is small and slender with short legs (Fig. 1). Its head is elongated with a pointed muzzle and small ears (Csurhes & Fisher 2010). The mongoose’s tail is muscular at the bottom and tapers gradually throughout its length, it also possess five toes that contains retractable claws. Its body length is between 50-67 cm for females and 54-67 cm for males. Its weight ranges from 305-662 grams. Their bodies are covered with short hair that is coloured pale to dark brown with golden flecks (Csurhes & Fisher 2010). Both males and females have an extensible anal pad with glands that are ducted lateral to the anus. ECOLOGY. Its habitat range is the largest in the family Herpestidae. It can thrive in a large range of habitats inclusive of agricultural land, coastal areas, natural forests, planted forests, grassland, wetland areas. However, climatically it is best able to survive in tropical zones (Csurhes & Fisher 2010). Carnivorous, with a varied and opportunistic diet, this diet is dependent on the habitat it is in and the food availability. This diet includes small mammals, UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour birds, reptiles, invertebrates and plant matter. -

Report of Rapid Biodiversity Assessments at Cenwanglaoshan Nature Reserve, Northwest Guangxi, China, 1999 and 2002

Report of Rapid Biodiversity Assessments at Cenwanglaoshan Nature Reserve, Northwest Guangxi, China, 1999 and 2002 Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden in collaboration with Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region Forestry Department Guangxi Forestry Survey and Planning Institute South China Institute of Botany South China Normal University Institute of Zoology, CAS March 2003 South China Forest Biodiversity Survey Report Series: No. 27 (Online Simplified Version) Report of Rapid Biodiversity Assessments at Cenwanglaoshan Nature Reserve, Northwest Guangxi, China, 1999 and 2002 Editors John R. Fellowes, Bosco P.L. Chan, Michael W.N. Lau, Ng Sai-Chit and Gloria L.P. Siu Contributors Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden: Gloria L.P. Siu (GS) Bosco P.L. Chan (BC) John R. Fellowes (JRF) Michael W.N. Lau (ML) Lee Kwok Shing (LKS) Ng Sai-Chit (NSC) Graham T. Reels (GTR) Roger C. Kendrick (RCK) Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region Forestry Department: Xu Zhihong (XZH) Pun Fulin (PFL) Xiao Ma (XM) Zhu Jindao (ZJD) Guangxi Forestry Survey and Planning Institute (Comprehensive Tan Wei Fu (TWF) Planning Branch): Huang Ziping (HZP) Guangxi Natural History Museum: Mo Yunming (MYM) Zhou Tianfu (ZTF) South China Institute of Botany: Chen Binghui (CBH) Huang Xiangxu (HXX) Wang Ruijiang (WRJ) South China Normal University: Li Zhenchang (LZC) Chen Xianglin (CXL) Institute of Zoology CAS (Beijing): Zhang Guoqing (ZGQ) Chen Deniu (CDN) Nanjing University: Chen Jianshou (CJS) Wang Songjie (WSJ) Xinyang Teachers’ College: Li Hongjing (LHJ) Voluntary specialist: Keith D.P. Wilson (KW) Background The present report details the findings of visits to Northwest Guangxi by members of Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden (KFBG) in Hong Kong and their colleagues, as part of KFBG's South China Biodiversity Conservation Programme. -

The Small Indian Mongoose Herpestes Auropuncatus in The

The Small Indian Mongoose Herpestes auropuncatus (Hodgson 1836)in the Balkans A synopsis of it’s introduction and recent information. David Bird Background 1.The Area • The Mediterranean basin to which the Balkans and the Adriatic sea belong is regarded as a one of the biodiversity hotspots especially where Reptiles and Amphibians are concerned (Myers,N.et.al 2000) with several endemic species and subspecies so should be a conservation priority for Europe. The Balkans is not only important for herpetofauna but for many other taxa and has a book dedicated to it (Griffiths,H.I et al. 2004). Chapter 10 of the book concerns the herpetofauna giving details of the number of endemic species for specific areas (Džukić & Kalezić 2004) the so called “Adriatic triangle” which covers Montenegro and adjacent Albania & Croatia having 10 endemic species. A recent checklist and bibliography has been produced for Croatia (Jelić 2014). Any invasive alien predator becoming widespread in this region may have dire consequences for its herpetological biodiversity . 2. The Problem itself • The Small Indian Mongoose has been successfully introduced into many areas around the World especially on islands for biological control of pest and unwanted species especially snakes but is now considered to be one of the worst invasive animals appearing on the I.U.C.N.’s worst 100 invasive species list ( I.U.C.N. 2000). Island species with no experience of predatory mammals have been badly affected with some species of herpetofauna having become extinct (Honneger,R.E. 1981). At least 64 islands around the World have this mongoose on them and they have been eradicated from 6 islands. -

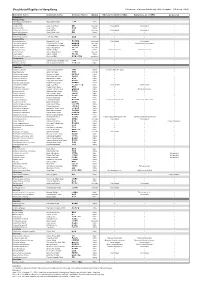

Checklist of Reptiles in Hong Kong © Programme of Ecology & Biodiversity, HKU (Last Update: 10 September 2012)

Checklist of Reptiles in Hong Kong © Programme of Ecology & Biodiversity, HKU (Last Update: 10 September 2012) Scientific name Common name Chinese Name Status Ades & Kendrick (2004) Karsen et al. (1998) Uetz et al. Testudines Platysternidae Platysternon megacephalum Big-headed Terrapin 大頭龜 Native Cheloniidae Caretta caretta Loggerhead Turtle 蠵龜 Uncertain Not included Not included Chelonia mydas Green Turtle 緣海龜 Native Eretmochelys imbricata Hawksbill Turtle 玳瑁 Uncertain Not included Not included Lepidochelys olivacea Pacific Ridley Turtle 麗龜 Native Dermochelyidae Dermochelys coriacea Leatherback Turtle 稜皮龜 Native Geoemydidae Cuora amboinensis Malayan Box Turtle 馬來閉殼龜 Introduced Not included Not included Cuora flavomarginata Yellow-lined Box Terrapin 黃緣閉殼龜 Uncertain Cistoclemmys flavomarginata Cuora trifasciata Three-banded Box Terrapin 三線閉殼龜 Native Mauremys mutica Chinese Pond Turtle 黃喉水龜 Uncertain Mauremys reevesii Reeves' Terrapin 烏龜 Native Chinemys reevesii Chinemys reevesii Ocadia sinensis Chinese Striped Turtle 中華花龜 Uncertain Sacalia bealei Beale's Terrapin 眼斑水龜 Native Trachemys scripta elegans Red-eared Slider 巴西龜 / 紅耳龜 Introduced Trionychidae Palea steindachneri Wattle-necked Soft-shelled Turtle 山瑞鱉 Uncertain Pelodiscus sinensis Chinese Soft-shelled Turtle 中華鱉 / 水魚 Native Squamata - Serpentes Colubridae Achalinus rufescens Rufous Burrowing Snake 棕脊蛇 Native Achalinus refescens (typo) Ahaetulla prasina Jade Vine Snake 綠瘦蛇 Uncertain Amphiesma atemporale Mountain Keelback 無顳鱗游蛇 Native -

P. 1 AC27 Inf. 7 (English Only / Únicamente En Inglés / Seulement

AC27 Inf. 7 (English only / únicamente en inglés / seulement en anglais) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________ Twenty-seventh meeting of the Animals Committee Veracruz (Mexico), 28 April – 3 May 2014 Species trade and conservation IUCN RED LIST ASSESSMENTS OF ASIAN SNAKE SPECIES [DECISION 16.104] 1. The attached information document has been submitted by IUCN (International Union for Conservation of * Nature) . It related to agenda item 19. * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat or the United Nations Environment Programme concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. AC27 Inf. 7 – p. 1 Global Species Programme Tel. +44 (0) 1223 277 966 219c Huntingdon Road Fax +44 (0) 1223 277 845 Cambridge CB3 ODL www.iucn.org United Kingdom IUCN Red List assessments of Asian snake species [Decision 16.104] 1. Introduction 2 2. Summary of published IUCN Red List assessments 3 a. Threats 3 b. Use and Trade 5 c. Overlap between international trade and intentional use being a threat 7 3. Further details on species for which international trade is a potential concern 8 a. Species accounts of threatened and Near Threatened species 8 i. Euprepiophis perlacea – Sichuan Rat Snake 9 ii. Orthriophis moellendorfi – Moellendorff's Trinket Snake 9 iii. Bungarus slowinskii – Red River Krait 10 iv. Laticauda semifasciata – Chinese Sea Snake 10 v. -

List of Reptile Species in Hong Kong

List of Reptile Species in Hong Kong Family No. of Species Common Name Scientific Name Order TESTUDOFORMES Cheloniidae 4 Loggerhead Turtle Caretta caretta Green Turtle Chelonia mydas Hawksbill Turtle Eretmochelys imbricata Olive Ridley Turtle Lepidochelys olivacea Dermochelyidae 1 Leatherback Turtle Dermochelys coriacea Emydidae 1 Red-eared Slider * Trachemys scripta elegans Geoemydidae 3 Three-banded Box Turtle Cuora trifasciata Reeves' Turtle Mauremys reevesii Beale's Turtle Sacalia bealei Platysternidae 1 Big-headed Turtle Platysternon megacephalum Trionychidae 1 Chinese Soft-shelled Turtle Pelodiscus sinensis Order SQUAMATA Suborder LACERTILIA Agamidae 1 Changeable Lizard Calotes versicolor Lacertidae 1 Grass Lizard Takydromus sexlineatus ocellatus Scincidae 11 Chinese Forest Skink Ateuchosaurus chinensis Long-tailed Skink Eutropis longicaudata Chinese Skink Plestiodon chinensis chinensis Five-striped Blue-tailed Skink Plestiodon elegans Blue-tailed Skink Plestiodon quadrilineatus Vietnamese Five-lined Skink Plestiodon tamdaoensis Slender Forest Skink Scincella modesta Reeve's Smooth Skink Scincella reevesii Brown Forest Skink Sphenomorphus incognitus Indian Forest Skink Sphenomorphus indicus Chinese Waterside Skink Tropidophorus sinicus Varanidae 1 Common Water Monitor Varanus salvator Dibamidae 1 Bogadek's Burrowing Lizard Dibamus bogadeki Gekkonidae 8 Four-clawed Gecko Gehyra mutilata Chinese Gecko Gekko chinensis Tokay Gecko Gekko gecko Bowring's Gecko Hemidactylus bowringii Brook's Gecko* Hemidactylus brookii House Gecko* Hemidactylus -

Flavor Preference of Oral Rabies Vaccine Baits by Small Indian Mongooses (Herpestes Auropunctatus) in Southwestern Puerto Rico

Flavor Preference of Oral Rabies Vaccine Baits by Small Indian Mongooses (Herpestes auropunctatus) in Southwestern Puerto Rico Are R. Berentsen and Fabiola B. Torres-Toledo USDA APHIS, Wildlife Services, National Wildlife Research Center, Fort Collins, Colorado Mel J. Rivera-Rodriguez USDA APHIS, Wildlife Services, Auburn, Alabama Amy J. Davis, and Amy T. Gilbert USDA APHIS, Wildlife Services, National Wildlife Research Center, Fort Collins, Colorado ABSTRACT: The small Indian mongoose is an invasive pest species and rabies reservoir in Puerto Rico and other islands in the Caribbean. In the United States and Europe, rabies in wild carnivores is largely controlled through oral rabies vaccination (ORV), but no ORV program for mongooses exists. The oral rabies vaccine currently licensed for use in wild carnivores in the United States has not been reported as immunogenic for mongooses. A mongoose-specific bait has been developed but field-based bait flavor preference trials have not been performed in Puerto Rico. We evaluated removal of egg-flavored (treatment) vs. unflavored (control), water- filled placebo ORV baits in a subtropical dry forest in southwestern Puerto Rico from 2014-2015. During six trials at four plots we distributed 350 baits (175 treatment and 175 control) and monitored baits for five days or until at least 50% of baits had been removed or were rendered unavailable to mongooses due to inundation by fire ants. The estimated overall probability of bait removal within five days was 85% (95% CI 75-91%) and 45% (95% CI 35-55%) for treatment and control baits, respectively. Removal rate estimates in the spring were 95% (95% CI 86-98%) and 63% (95% CI 49-76%) for treatment and control baits, respectively. -

Biology and Impacts of Pacific Island Invasive Species. 1. a Worldwide

Biology and Impacts of Pacific Island Invasive Species. 1. A Worldwide Review of Effects of the Small Indian Mongoose, Herpestes javanicus (Carnivora: Herpestidae)1 Warren S. T. Hays2 and Sheila Conant3 Abstract: The small Indian mongoose, Herpestes javanicus (E. Geoffroy Saint- Hilaire, 1818), was intentionally introduced to at least 45 islands (including 8 in the Pacific) and one continental mainland between 1872 and 1979. This small carnivore is now found on the mainland or islands of Asia, Africa, Europe, North America, South America, and Oceania. In this review we document the impact of this species on native birds, mammals, and herpetofauna in these areas of introduction. The small Indian mongoose has been 1), typically has an adult body mass in the introduced to numerous islands, including range of 300 to 900 g and a body length eight in the Pacific. Beyond its native range from 500 to 650 mm (Nellis 1989). It has in southern Asia, this species now occurs on the slender body shape typical of the herpes- islands or mainlands elsewhere in Asia, Africa, tid family, with short legs, short brown fur, Europe, North America, South America, and and a tail that makes up roughly 40% of the Oceania. Its negative effects on native biota animal’s total length. Dentition is 3:1:4:2, of these areas are a concern to natural-area with a wide carnassial shear region. Females managers. have 36 chromosomes and males have 35, because the Y chromosome has translocated name onto an autosome (Fredga 1965). A more complete species description may Herpestes javanicus (E. -

Human-Snake Conflict Patterns in a Dense Urban-Forest Mosaic Landscape

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 14(1):143–154. Submitted: 9 June 2018; Accepted: 25 February 2019; Published: 30 April 2019. HUMAN-SNAKE CONFLICT PATTERNS IN A DENSE URBAN-FOREST MOSAIC LANDSCAPE SAM YUE1,3, TIMOTHY C. BONEBRAKE1, AND LUKE GIBSON2 1School of Biological Sciences, University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong, China 2School of Environmental Science and Engineering, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen, China 3Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract.—Human expansion and urbanization have caused an escalation in human-wildlife conflicts worldwide. Of particular concern are human-snake conflicts (HSC), which result in over five million reported cases of snakebite annually and significant medical costs. There is an urgent need to understand HSC to mitigate such incidents, especially in Asia, which holds the highest HSC frequency in the world and the highest projected urbanization rate, though knowledge of HSC patterns is currently lacking. Here, we examined the relationships between season, weather, and habitat type on HSC incidents since 2002 in Hong Kong, China, which contains a mixed landscape of forest, dense urban areas, and habitats across a range of human disturbance and forest succession. HSC frequency peaked in the autumn and spring, likely due to increased activity before and after winter brumation. There were no considerable differences between incidents involving venomous and non-venomous species. Dense urban areas had low HSC, likely due to its inhospitable environment for snakes, while forest cover had no discernible influence on HSC. We found that disturbed or lower quality habitats such as shrubland or areas with minimal vegetation had the highest HSC, likely because such areas contain intermediate densities of snakes and humans, and intermediate levels of disturbance.