6. Photography, Authenticity and Victoria's Aborigines Protection Act

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY and CULTURE Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc

ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY AND CULTURE Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University, and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National University. Aboriginal History Inc. is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to the Editors, Aboriginal History Inc., ACIH, School of History, RSSS, 9 Fellows Road (Coombs Building), The Australian National University, Acton, ACT, 2601, or [email protected]. WARNING: Readers are notified that this publication may contain names or images of deceased persons. ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY AND CULTURE UNCLE ROY PATTERSON AND JENNIFER JONES Published by ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760464066 ISBN (online): 9781760464073 WorldCat (print): 1224453432 WorldCat (online): 1224452874 DOI: 10.22459/OTL.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photograph: Patterson family photograph, circa 1904 This edition © 2020 ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. Contents Acknowledgements ....................................... vii Note on terminology ......................................ix Preface .................................................xi Introduction: Meeting and working with Uncle Roy ..............1 Part 1: Sharing Taungurung history 1. -

Fighting Extinction Challenge Teacher Answers Middle Years 9-10

Fighting Extinction Challenge Teacher Answers Middle Years 9-10 Wurundjeri Investigation We are all custodians of the land, just as the Wurundjeri have been for thousands of years. During your independent investigation around the Sanctuary look for ways that the Wurundjeri people lived on country and record these observations in the box below. Look (what you saw) Hear (what you heard) I wonder… (questions to ask an expert or investigate back at school ) Bunjil Soundscapes Waa Information from education Mindi officers Signs about plant uses Dreaming stories at feature shows Signs about animal dreaming Information about Wurundjeri stories Seasons Sculptures Didjeridoo Scar Tree Bark Canoe Gunyah Information about Coranderrk William Barak sculpture Information about William Barak Artefacts (eg eel trap, marngrook, possum skin cloak) 1. Identify and explain how did indigenous people impact upon their environment? Indigenous people changed the landscape using fire stick farming which also assisted hunting Aboriginal people used their knowledge of the seasons to optimise hunting, gathering, eel farming and more Aboriginal people used organic local materials to create tools to assist them with hunting and gathering their food i.e. eel traps, woven grass baskets, rock fish traps etc. They only ever took what they needed from the land and had a deep respect and spiritual connection to the land and their surroundings. 2. How are humans impacting on natural resources in today’s society? How does this affect wildlife? When the land is disrespected, damaged or destroyed, this can have real impact on the wellbeing of people, plants and animals. European settlers and modern day humans have caused land degradation by: •Introducing poor farming practices causing land degradation •Introducing noxious weeds •Changing water flow courses and draining wetlands •Introducing feral animals •Destroying habitat through urbanization, logging and farming practices 3. -

3 Researchers and Coranderrk

3 Researchers and Coranderrk Coranderrk was an important focus of research for anthropologists, archaeologists, naturalists, historians and others with an interest in Australian Aboriginal people. Lydon (2005: 170) describes researchers treating Coranderrk as ‘a kind of ethno- logical archive’. Cawte (1986: 36) has argued that there was a strand of colonial thought – which may be characterised as imperialist, self-congratulatory, and social Darwinist – that regarded Australia as an ‘evolutionary museum in which the primi- tive and civilised races could be studied side by side – at least while the remnants of the former survived’. This chapter considers contributions from six researchers – E.H. Giglioli, H.N. Moseley, C.J.D. Charnay, Rev. J. Mathew, L.W.G. Büchner, and Professor F.R. von Luschan – and a 1921 comment from a primary school teacher, named J.M. Provan, who was concerned about the impact the proposed closure of Coranderrk would have on the ability to conduct research into Aboriginal people. Ethel Shaw (1949: 29–30) has discussed the interaction of Aboriginal residents and researchers, explaining the need for a nuanced understanding of the research setting: The Aborigine does not tell everything; he has learnt to keep silent on some aspects of his life. There is not a tribe in Australia which does not know about the whites and their ideas on certain subjects. News passes quickly from one tribe to another, and they are quick to mislead the inquirer if it suits their purpose. Mr. Howitt, Mr. Matthews, and others, who made a study of the Aborigines, often visited Coranderrk, and were given much assistance by Mr. -

Walata Tyamateetj a Guide to Government Records About Aboriginal People in Victoria

walata tyamateetj A guide to government records about Aboriginal people in Victoria Public Record Office Victoria and National Archives of Australia With an historical overview by Richard Broome walata tyamateetj means ‘carry knowledge’ in the Gunditjmara language of western Victoria. Published by Public Record Office Victoria and National Archives of Australia PO Box 2100, North Melbourne, Victoria 3051, Australia. © State of Victoria and Commonwealth of Australia 2014 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the National Archives of Australia and Public Record Office Victoria. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be directed to the Publishing Manager, National Archives of Australia, PO Box 7425, Canberra Business Centre ACT 2610, Australia, and the Manager, Community Archives, Public Record Office Victoria, PO Box 2100, North Melbourne Vic 3051, Australia. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Victoria. Public Record Office, author. walata tyamateetj: a guide to government records about Aboriginal people in Victoria / Public Record Office Victoria and National Archives of Australia; with an historical overview by Richard Broome. ISBN 9780987283702 (paperback) ISBN 9780987283719 (ebook) Victoria. Public Record Office.–Catalogs. National Archives of Australia. Melbourne Office.–Catalogs. Aboriginal Australians–Victoria–Archives. Aboriginal Australians–Victoria–Bibliography–Catalogs. Public records–Victoria–Bibliography–Catalogs. Archives–Victoria–Catalogs. Victoria–Archival resources. National Archives of Australia. Melbourne Office, author. Broome, Richard, 1948–. 016.99450049915 Public Record Office Victoria contributors: Tsari Anderson, Charlie Farrugia, Sebastian Gurciullo, Andrew Henderson and Kasia Zygmuntowicz. National Archives of Australia contributors: Grace Baliviera, Mark Brennan, Angela McAdam, Hilary Rowell and Margaret Ruhfus. -

'The Happiest Time of My Life …': Emotive Visitor Books and Early

‘The happiest time of my life …’: Emotive visitor books and early mission tourism to Victoria’s Aboriginal reserves1 Nikita Vanderbyl On the afternoon of 16 January 1895, a group of visitors to the Gippsland Lakes, Victoria, gathered to perform songs and hymns with the Aboriginal residents of Lake Tyers Aboriginal Mission. Several visitors from the nearby Lake Tyers House assisted with the preparations and an audience of Aboriginal mission residents and visitors spent a pleasant summer evening performing together and enjoying refreshments. The ‘program’ included an opening hymn by ‘the Aborigines’ followed by songs and hymns sung by friends of the mission, the missionary’s daughter and a duet by two Aboriginal women, Mrs E. O’Rourke and Mrs Jennings, who in particular received hearty applause for their performance of ‘Weary Gleaner’. The success of this shared performance is recorded by an anonymous hand in the Lake Tyers visitor book, noting that 9 pounds 6 shillings was collected from the enthusiastic audience.2 The missionary’s wife, Caroline Bulmer, was most likely responsible for this note celebrating the success of an event that stands out among the comments of visitors to Lake Tyers. One such visitor was a woman named Miss Florrie Powell who performed the song ‘The Old Countess’ after the duet by Mrs O’Rourke and Mrs Jennings. She wrote effusively in the visitor book that ‘to give you an idea 1 Florrie Powell 18 January 1895, Lake Tyers visitor book, MS 11934 Box 2478/5, State Library of Victoria. My thanks to Tracey Banivanua Mar, Diane Kirkby, Catherine Bishop, Lucy Davies and Kate Laing for their feedback on an earlier draft of this article, and to Richard White for mentoring as part of a 2015 Copyright Agency Limited Bursary. -

Today We're Alive – Generating Performance in a Cross-Cultural

Faculty of Education and Social Work The University of Sydney Today We’re Alive – generating performance in a cross-cultural context, an Australian experience. By Linden Wilkinson A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2014 Faculty of Education and Social Work Office of Doctoral Studies AUTHOR’S DECLARATION This is to certify that: l. this thesis comprises only my original work towards the Doctorate of Philosophy. ll. due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all other material used. lll. the thesis does not exceed the word length for this degree. lV. no part of this work has been used for the award of another degree. V. this thesis meets the University of Sydney’s Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) requirements for the conduct of this research. Signature: Name: Linden Wilkinson Date: 17th September, 2014 Acknowledgements I wish to acknowledge my supervisors, Associate Professor Dr Michael Anderson and Dr Paul Dwyer, for their support, rigour and encouragement in relation to this project. I would also like to thank my family for their patience. And I would like to express my profound gratitude to everyone, who shared their time, their wisdom and their memories so willingly to this undertaking. The Myall Creek story goes on… Finally to the actors – to Fred, Anna, Lily, Genevieve, Aunty Rhonda & Terry in 2011, to Bjorn, Rosie, Frankie & Russell in 2013 – thanks for your skill, your trust, your imagination and your humour. And thanks for saying, “Yes.” i Today We’re Alive generating performance in a cross-cultural context, an Australian experience Abstract Using a mixed methods approach this thesis explores the construction and dissemination of a cross-cultural play within the Australian context. -

A Brief History of the Lake Tyers Aboriginal Community; the Lake Tyers Aboriginal Community Has Had a Controversial History Since Being Set up in 1861

A brief history of the Lake Tyers Aboriginal community; The Lake Tyers Aboriginal community has had a controversial history since being set up in 1861. Waters, Jeff . ABC Premium News ; Sydney [Sydney]21 Dec 2013. ProQuest document link ABSTRACT (ABSTRACT) Nine years later, Victoria's Aboriginal protection board voted for a policy of concentrating all 'full-blood' and 'half- caste' Aboriginal people on the Lake Tyers Station. In an interview she told ABC Gippsland her childhood as one of 11 children at Lake Tyers was "happy and carefree", but that all changed when her family was pressured to leave the mission. According to the ABC's Mission Beats website: "Between 1956 and 1965, the residents requested, protested and petitioned for Lake Tyers Mission Station to become an independent, Aboriginal run farming cooperative. This campaign received support and assistance from the Melbourne-based Aborigines Advancement League (AAL), with Pastor Sir Doug Nichols providing a much-needed voice among Melbourne's bureaucrats. When the Board moved to close Lake Tyers in February 1963, Nichols resigned his position on the Board in protest." FULL TEXT The traditional owners of the land which includes what is now called Lake Tyers in East Gippsland are the Krowathunkooloong clan - one of five forming the Gunaikurnai nation, who largely resisted white settlement in the area. In 1861 the Lake Tyers Mission Station was established by the Church of England missionary Reverend John Bulmer, to house some of the Gunaikurnai survivors of the conflict. The peninsula, which has a lake on each side, was known to its traditional owners as Bung Yarnda. -

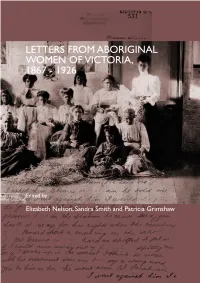

Letters from Aboriginal Women of Victoria, 1867-1926, Edited by Elizabeth Nelson, Sandra Smith and Patricia Grimshaw (2002)

LETTERS FROM ABORIGINAL WOMEN OF VICTORIA, 1867 - 1926 LETTERS FROM ABORIGINAL WOMEN OF VICTORIA, 1867 - 1926 Edited by Elizabeth Nelson, Sandra Smith and Patricia Grimshaw History Department The University of Melbourne 2002 © 2002 Copyright is held on individual letters by the individual contributors or their descendants. No reproduction without permission. All rights reserved. Published in 2002 by The History Department The University of Melbourne Melbourne, Australia The National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Letters from aboriginal women in Victoria, 1867-1926. ISBN 0 7340 2160 7. 1. Aborigines, Australian - Women - Victoria - Correspondence. 2. Aborigines, Australian - Women - Victoria - Social conditions. 3. Aborigines, Australian - Government policy - Victoria. 4. Victoria - History. I. Grimshaw, Patricia, 1938- . II. Nelson, Elizabeth, 1972- . III. Smith, Sandra, 1945- . IV. University of Melbourne. Dept. of History. (Series : University of Melbourne history research series ; 11). 305.8991509945 Front cover details: ‘Raffia workers at Coranderrk’ Museum of Victoria Photographic Collection Reproduced courtesy Museum Victoria Layout and cover design by Design Space TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 7 Map 9 Introduction 11 Notes on Editors 21 The Letters: Children and family 25 Land and housing 123 Asserting personal freedom 145 Regarding missionaries and station managers 193 Religion 229 Sustenance and material assistance 239 Biographical details of the letter writers 315 Endnotes 331 Publications 357 Letters from Aboriginal Women of Victoria, 1867 - 1926 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We have been helped to pursue this project by many people to whom we express gratitude. Patricia Grimshaw acknowledges the University of Melbourne Small ARC Grant for the year 2000 which enabled transcripts of the letters to be made. -

1 Aboriginal Mission Tourism in Nineteenth Century Victoria

1 Aboriginal Mission Tourism in Nineteenth Century Victoria This study is concerned with the history of tourism at the Coranderrk Aboriginal station that operated near Healesville some 65km northeast of Melbourne from 1863 until its formal closure in 1924. The title of this account is ‘A peep at the Blacks’. It is adapted from the title of an 1877 newspaper article written by John Stanley James, the nineteenth century travel writer, who used the pseudonym ‘The Vagabond’. He was one of many journalists, researchers, and dignitaries who visited Coranderrk during its 60 years of operation to gaze at the residents. Coranderrk was one of six reserves that operated across Victoria in the second half of the nineteenth century (see Figure 1.1). Although all six reserves were places of Aboriginal incarceration, Cor- anderrk, because of its proximity to Melbourne, became emblematic in shaping the views of Melbourne-based policy makers (Lydon, 2002: 81). Many tropes or themes mediated the tourist gaze – the view that they were both a ‘fossil race’ and a ‘dying race’ made it imperative that they be researched before they became non-existent. Before commencing a fine-grained study of Coranderrk it is necessary to take heed of Hall’s and Tucker’s (2004: 8) observation that ‘Any understanding of the cre- ation of a destination… involves placing the development of the representation of that destination within the context of the historical consumption and production of places and the means by which places have become incorporated within the global capital system’. In terms of an international culture network, Lydon (2002) has shown how images of Coranderrk Aboriginal people became scientific currency within an inter- national network extending as far afield as England, Italy, Russia, and France. -

Indigenous and Minority Placenames

Indigenous and Minority Placenames Indigenous and Minority Placenames Australian and International Perspectives Edited by Ian D. Clark, Luise Hercus and Laura Kostanski Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Clark, Ian D., 1958- author. Title: Indigenous and minority placenames : Australian and international perspectives Ian D. Clark, Luise Hercus and Laura Kostanski. Series: Aboriginal history monograph; ISBN: 9781925021622 (paperback) 9781925021639 (ebook) Subjects: Names, Geographical--Aboriginal Australian. Names, Geographical--Australia. Other Authors/Contributors: Hercus, Luise, author. Kostanski, Laura, author. Dewey Number: 919.4003 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Nic Welbourn and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Notes on Contributors . .vii 1 . Introduction: Indigenous and Minority Placenames – Australian and International Perspectives . 1 Ian D. Clark, Luise Hercus, and Laura Kostanski 2 . Comitative placenames in central NSW . 11 David Nash 3. The diminutive suffix dool- in placenames of central north NSW 39 David Nash 4 . Placenames as a guide to language distribution in the Upper Hunter, and the landnám problem in Australian toponomastics . 57 Jim Wafer 5 . Illuminating the cave names of Gundungurra country . 83 Jim Smith 6 . Doing things with toponyms: the pragmatics of placenames in Western Arnhem Land . -

4 International Dignitaries and Their Impressions of Coranderrk

4 International Dignitaries and Their Impressions of Coranderrk Coranderrk was the site of many visits from international dignitaries, including royalty, and members of the political elite. This chapter looks at 14 of these visitors as diverse as media baron Lord Northcliffe to acclaimed English historian James Froude. Unfortunately we do not have details of the nature of every visit – in some cases we just have a matter-of-fact newspaper account that a visit took place. In other cases we have both newspaper accounts and published accounts from the dignitary. Where we have some detail we are able to reconstruct the performances the Cor- anderrk residents arranged for the visitors. Typically, these performances included boomerang throwing, spear throwing, and fire making. On some occasions the visi- tors were given gifts of baskets and clubs. On one very special occasion the visiting party was given a specially-made basket and some nicely carved emu eggs as gifts for the Queen. When the Victorian Governor Lord Brassey visited Coranderrk in late 1897, William Barak presented him with a picture of a corroboree painted in black on yellow on a slab of wood about 3 ft long by 2 ft high. When the new Anglican Bishop of Melbourne visited in October 1904 the Coranderrk people performed a corroboree with singing. In June 1910, artist Hugh Fisher of the Visual Instruction Committee of the Colonial Office visited Coranderrk to collect information and photographs and make paintings to be used in the preparation of educational lectures on Australia. At Coranderrk Fisher made a sketch of Anthony Anderson. -

Invasion and Dispossession

CORANDERRK Invasion and dispossession The Kulin clans who established the Coranderrk Aboriginal station in 1863 were true survivors. They had inhabited the lands and waters of central Victoria for thousands of years. Yet their world would change forever in 1835, when the first wave of British settlers arrived on their shores. These newcomers occupied the Kulin’s ancestral lands and claimed them as their own, bringing with them large herds of cattle and sheep, as well as firearms, alcohol and disease. At the heart of the ensuing conflict was the fundamental issue of land. To the original inhabitants it was an inseparable part of their identity, spirituality and way of life; to the newcomers, it was a vital source of economic wealth, and the primary reason why they had migrated to this part of the world. The British colonial invasion of Victoria was swift, as pastoralists, squatters and convict workers took possession of vast tracts of land around Port Phillip Bay.1 The introduction of large-scale pastoralism caused massive disruptions to local hunter-gatherer economies, and although the Kulin sought to defend their lands, they were soon overwhelmed by the sheer number of settlers who continued to arrive. Before long, the settlers had taken possession of most of the habitable land in Victoria, displacing the Kulin, as well as many other Aboriginal nations, and driving them to the edge of survival. The Aboriginal population of Victoria was greatly reduced as a result of colonisation.2 Those who survived were pushed to the fringes of colonial society and were not welcome in the newly founded city of Melbourne.