A Century of Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The African American Soldier at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, 1892-1946

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Anthropology, Department of 2-2001 The African American Soldier At Fort Huachuca, Arizona, 1892-1946 Steven D. Smith University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/anth_facpub Part of the Anthropology Commons Publication Info Published in 2001. © 2001, University of South Carolina--South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology This Book is brought to you by the Anthropology, Department of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE AFRICAN AMERICAN SOLDIER AT FORT HUACHUCA, ARIZONA, 1892-1946 The U.S Army Fort Huachuca, Arizona, And the Center of Expertise for Preservation of Structures and Buildings U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Seattle District Seattle, Washington THE AFRICAN AMERICAN SOLDIER AT FORT HUACHUCA, ARIZONA, 1892-1946 By Steven D. Smith South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology University of South Carolina Prepared For: U.S. Army Fort Huachuca, Arizona And the The Center of Expertise for Preservation of Historic Structures & Buildings, U.S. Army Corps of Engineer, Seattle District Under Contract No. DACW67-00-P-4028 February 2001 ABSTRACT This study examines the history of African American soldiers at Fort Huachuca, Arizona from 1892 until 1946. It was during this period that U.S. Army policy required that African Americans serve in separate military units from white soldiers. All four of the United States Congressionally mandated all-black units were stationed at Fort Huachuca during this period, beginning with the 24th Infantry and following in chronological order; the 9th Cavalry, the 10th Cavalry, and the 25th Infantry. -

Early Days at Fort Snelling

Library of Congress Early days at Fort Snelling. 420 EARLY DAYS AT FORT SNELLING. Previous to the organization of the Territory of Minnesota, in 1849, Fort Snelling was the only place of note beyond Prairie du Chien. For years it had been the point at which the missionary of the Cross, the man of science, the adventurous trader, made preparations for their journeys among the villages of the wandering Dakotas. Beautifully located on an elevated bluff, at the junction of the Minnesota and Mississippi, its massive walls make a strong impression on the mind of the traveler. Within its enclosure have been quartered some of the most efficient officers of the United States Army, who have received with hospitality the various scientific expeditions that have from time to time passed through the country. Its history and associations are full of interest and worthy of record in the Annals of Minnesota. On the island in front of the Fort, Pike encamped, and entered into negotiations for the site of the present Fort, as the extracts from his journal, published in a previous chapter show. In 1817, Major Long , in a report to the War Department, recommended the site for a permanent Fort. In 1819, three hundred men of the Sixth regiment, under the command of Colonel Leavenworth , left Detroit, for the purpose of commanding the Fort. They came by the way of Green Bay and Prairie du Chien. At this point a detachment was left, and the remainder ascended the Mississippi. On the 17th of September, they established a cantonment, on the South side of the Minnesota, at the present ferry. -

Fort Snelling Hosted One of 16 Officer Training Camps Established at Onset

Summer, 2017 Vol. XXV, No. 3 Fort Snelling hosted one of 16 officer training camps established at onset of World War I at Fort Snelling, 4,000 were accepted, and only about By Todd Adler 2,500 ultimately got commissions. The rest were deemed Todd Adler is an independent researcher and historian deficient in some way, either because they didn’t meas- with a special interest of Fort Snelling. He is on the board ure up to the army’s standards or because the vast num- of directors of the Fort Snelling Foundation and Friends of ber of candidates had to be culled. Many were dropped Fort Snelling. from the program through no serious fault of their own, but because there were too many applicants. When the United States joined WWI in April, 1917, the Candidates had to submit evidence and testimonials at- U.S. Army had just 200,000 personnel. In comparison, testing to their character, loyalty, education, and business Italy had 5.6 million men under arms, France and Great experience. The applications were then reviewed and di- Britain over 8 million, and Germany 11 million. Clearly, vided into A grade and B grade. Even after winnowing out the U.S. had catching up to do. In order to train the mas- a lot of candidates, there were still too many in the A sive number of men needed to fight, the army also grade category for the camp. Candidates came from all needed to recruit and train a new batch of officers to lead over Minnesota, Iowa, Nebraska, North Dakota, South them. -

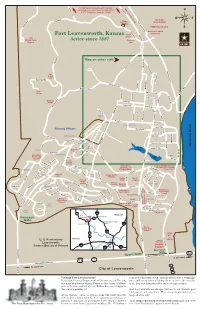

Leavenworth, Kansas, 1827-2004

THE HISTORY OF WEATHER OBSERVING IN LEAVENWORTH, KANSAS, 1827-2004 Including Fort Leavenworth and West Leavenworth General Henry Leavenworth, 1783-1834 From History of Fort Leavenworth 1827-1927 Current as of January 21, 2005 Prepared by: Stephen R. Doty Information Manufacturing Corporation Rocket Center, West Virginia This report was prepared for the Midwestern Regional Climate Center under the auspices of the Climate Database Modernization Program, NOAA's National Climatic Data Center, Asheville, North Carolina Executive Summary Weather observing in the Leavenworth, Kansas, area began in 1827 when the U.S. Army established a post at Fort Leavenworth. Military surgeons recorded observations at the Post Hospital and the Military Prison Hospital until the early 1900’s. Observations were then begun at the Army Airfield in 1926 and they continued through 1996. Meanwhile, Smithsonian Institution observers were recording the weather in Leavenworth beginning in 1857. These volunteer observers were followed by the U.S. Army Signal Service and Weather Bureau observers serving through 1893. Volunteer observers again began to record Leavenworth’s weather. The U.S. Federal Penitentiary was the site of the observations beginning in 1911 continuing through 1946 when Kansas Power and Light assumed the observing role at their generating plant, a role they continued until 1961. Radio station KCLO was the site of the observations from 1961 until 1973. The site moved to the municipal water plant in 1973 where observations continued until 1988. After this time the program moved to a series of individuals, a service that continues to this day. An U.S. Army Signal Service volunteer observer recorded observations in West Leavenworth from 1883 until 1888. -

Map of Military Road Markers Pottawatomie County 15 20 8 to Go to the St

Map of Military Road Markers Pottawatomie County 15 20 8 To go to the St. George cutoff turn east on US24 to Black Follow path to marker at Leavenworth County Go west on us highway #24 to St. Marys. Jack Road, turn south for about one mile to 1st Street, turn 39°10’16” N 96°36’42” W 1 left to Lincoln Avenue, turn left, go two blocks north to US24 and Grand Ave. (next to the Kansas State Historical Black Jack Spring. If coming from Manhattan Town Center 21 Eight Mile House marker) across the street from the St. Marys academy. go 7.3 Miles east on US24 to Black Jack Road. Follow path to the bridge that was built in 1998 Leavenworth County Road R 14 (Santa Fe Trail) and Easton 39°11’25” N 96°3’37” W 39°11’30” N 96°25’19” W 39°10’24” N 96°36’32” W Road (K192) 9 39°22’19” N 95°02’36” W 16 22 Continue west on US24 through St. Marys to K63, turn Continue north on Green Valley Road to Junietta Road and Turn around and return to parking lot. Distance walking - 2 right to Durink Street, turn left and it becomes Oregon Trail turn left or west for about four miles ( the road changes to .37 Mile and about ten minutes. Easton, Kansas Road (a gravel road). Continue west on Oregon Trail Road Blue River Road). The marker is on the north side of Blue to Pleasant View Road, turn right, continue west on Oregon From parking lot retrace same route to Fort Riley Blvd. -

Heavy Division Tactical Maneuver Planning Guides and the Army's

Tactical Alchemy: Heavy Division Tactical Maneuver Planning Guides and the Army’s Neglect of the Science of War A Monograph By Major Vincent J. Tedesco III United States Army School of Advanced Military Studies United States Army Command and General Staff College Fort Leavenworth, Kansas First Term AY 99-00 Approved for Public Release; Distribution is Unlimited SCHOOL OF ADVANCED MILITARY STUDIES MONOGRAPH APPROVAL Major Vincent J. Tedesco III Title of Monograph: Tactical Alchemy: Heavy Division Tactical Maneuver Planning Guides and the Army’s Neglect of the Science of War. Approved by: ______________________________________________ Monograph Director James J. Schneider, Ph.D. ______________________________________________ Director, School of Advanced COL Robin P. Swan, MMAS Military Studies ______________________________________________ Director, Graduate Degree Philip J. Brookes, Ph. D. Program Accepted this 13th Day of December, 1999 ABSTRACT Tactical Alchemy: Heavy Division Tactical Maneuver Planning Guides and the Army’s Neglect of the Science of War. In the wake of the Cold War, the Army increasingly finds its institutional focus shifting away from preparing for sustained mechanized land combat. This trend serves the Army’s immediate operational needs and addresses its perceived need to demonstrate relevancy, but it also raises an important question. How can the Army preserve for future use its hard won expertise in combined arms mechanized warfare? The art of these operations is well documented in doctrine, tactics, techniques, and procedures, but the science of time, space, and combat power in heavy division operations is not. In effect, the Army is already lapsing into what J.F.C. Fuller described as “military alchemy,” denying the science of war in favor of theorizing on its art. -

Fort Union and the Santa Fe Trail

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 36 Number 1 Article 3 1-1-1961 Fort Union and the Santa Fe Trail Robert M. Utley Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Utley, Robert M.. "Fort Union and the Santa Fe Trail." New Mexico Historical Review 36, 1 (1961). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol36/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. FORT UNION AND THE SANTA FE TRAIL By ROBERT M. UTLEY * OR over half a century a wide band of wagon ruts joined FNew Mexico, first as a Mexican province, later as Ameri can territory, to the Missouri frontier and the States. Be tween the American conquest in 1846 and the coming of the railroad in the decade of the seventies, the Santa Fe Trail was a momentous avenue of commerce, transportation, and communication. In Kansas the Trail divided, to enter New Mexico by two routes. The Cimarron Cutoff, shortest but most dangerous fork, turned southwest from the Arkansas River and followed the dry course of the Cimarron River into the Oklahoma pan handle, reaching New Mexico near present Clayton..The Mountain Branch, 100 miles longer and with the treacherous barrier of Raton Pass, kept to the north bank of the Arkansas, turned southwest along the base of the Rockies, and dropped into New Mexico at Raton Pass. -

THE COMBINED ARMS CENTER and FORT LEAVENWORTH VOLUNTEER and SPECIAL AWARDS and RECOGNITION HANDBOOK Version 1

THE COMBINED ARMS CENTER AND FORT LEAVENWORTH VOLUNTEER AND SPECIAL AWARDS AND RECOGNITION HANDBOOK Version 1 Please contact the Combined Arms Center Secretary to the General Office for comments, questions, or any discovery of obsolete or incorrect information. CAC SGS email: [email protected] CAC SGS Phone Number: 684-0020 As of 14 April 2021 CAC & FLKS Volunteer and Special Awards and Recognition Handbook 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS MAIN SECTIONS AND HEADERS Page # Section I: General Overview 5 1.1 Purpose 5 1.2 Awards Overview 5 1.3 Preparing a Nomination 6 1.4 Presentation of the Award(s) 8 Section II: Volunteer Information 9 2.1 Volunteer Code of Ethics 9 2.2 Types of Volunteers 9 2.3 Volunteer Management Information System 10 2.4 Manual Tracking of Volunteer Hours 12 2.5 Volunteer Recognition Requirements and Recommendations 12 Section III: Summary of Types of Awards 13 Section IV: Unit Directorate/Organizational Awards 36 4.1 Certificate of Appreciation/Achievement 36 4.2 Audie Murphy Volunteer Service Award Certificate 37 4.3 Volunteer Spotlight 38 4.4 Star of the Frontier 39 4.5 Keeper of the Tower 40 Section V: Installation Awards and Recognition 41 5.1 CAC Child of the Frontier Certificate of Appreciation 41 5.2 CAC Newborn Request for Orders 42 5.3 The Elizabeth Smith Award 43 5.4. The Joanne von Schlemmer Award 44 5.5 Twilight Toll Certificate of Recognition 45 5.6 Outstanding Spouse Volunteer of the Year 46 5.7 Outstanding Soldier Volunteer of the Year 47 5.8 Outstanding Youth Volunteer of the Year 48 5.9 Department of the Army Civilian Volunteer of the Year 49 5.10 Outstanding Family Volunteer of the Year 50 Section VI: TRADOC Volunteer Award 51 6.1 Margaret C. -

FT LVN Post Map JAN 2018

Kickapoo Rd To Military Correctional Complex: USDB Rd Joint Regional Correctional Facility (JRCF) N & U.S. Disiplinary Barracks (USDB) To Kinder Range W E USMP Sherman Sheridan Dr Cemetery Chief Joseph Loop Army Airfield Sabalu Road FMWR Flying Activity S Sheridan Dr Motorcycle Safety Classroom Fort Leavenworth, Kansas Thrift USDB Rd Shop 15th Military Police Active since 1827 Envision Brigade Store Map on other side Sheridan Dr Bluntville Ave Mcclellan Ave Mcclellan Sylvan Trail Chief Joseph Loop Rod & Gun Club Wainwright Rd Harrison Dr McPherson Ave McPherson Ave Riley Ave McClellan Ave Hunt Lodge McPherson Ave Nez Perce Way Riverside Ave Sumner Place W Warehouse Rd Brunner Organ Ave Rd Warehouse E Range Scott Ave Kearny Ave Sheridan Drive Kearny Ave Lowe Dr Main Post Biddle Blvd Custer Ave Nez Perce Scott Ave McClellan Ave Grant Ave Pope Ave Thomas Ave Pope Ave Infantry Barracks Augur Ave Housing Villages Doniphan Dr Meade Ave Ave Upton Sheridan Dr East Cheyenne Buford Ave 9th Cav Rd StanleyStanley Ave McDowell Ave McDowell Reynolds Ave HancockNew Ave Oregon Biddle Blvd Missouri River Merritt Ave Gibbon 9th Cav Ct Sedgwick Ave CheyenneIowa Ave Hancock Lake Pool Pick Ave 5th Artillery Rd Rose Loop Upper Kansa Old Oregon MacArthur Cody Rd Wint Sherman Ave Elementary Walker Ave Smith School Lake Wint Ave On Post 4th Artillery Rd Dragoon Dr Housing Grant Ave (FLFHC) 14th Cavalry Loop Trails West Swift St Lewis & Clark Center Clubhouse & Stimson CommandAve & General Staff Lower Kansa Fairway Grille College (CGSC) Pottawatomie Kansas Ave -

An Old Santa Fe Trail Map Recovered

An Old Santa Fe Trail Map Recovered By Margaret Sears ample of disparity among various figures reported by both freighters. [This may be simply that the actual shipment [Due to space limitations,the maps identified herein, which was more than the contract.] are the subject of this article, are located on the Santa Fe Trail Association website www.santafetrail.org/publications/new- Upon returning to Fort Leavenworth the freighters turned research/ . The advantage of online copies is that they can be in their records. The government determined that the mile- enlarged to see details more clearly. Hard copies are available age reported was greater than the distance of the Santa Fe from SFTA. Email [email protected] or call 620-285-2054.] Trail the freighters traveled. All trains did not take the same route. Some took the Mountain Route, or Raton Route as Some years ago the late William Chalfant, renowned Santa that alternate track was also called, through southern Colo- Fe Trail historian/author, informed the National Park Ser- rado, while others took the Cimarron Route, which crossed vice, National Trails Intermountain Region (NTIR) office the Arkansas River 12 miles east of present Dodge City, in Santa Fe that he had uncovered an article from the July then entered into the present Oklahoma panhandle. Nor Great Bend Register 20, 1876, [Kansas] stating: were any military orders given that they follow a particular route.5 A “train,” as described by the U.S. Court of Claims During the years 1863, 1864, and 1865 the government consisted of 25 wagons, each drawn by 4-6 yoke of oxen.6 contracted with a firm in Leavenworth to transport freight from Fort Leavenworth to Fort Union, at a certain To compound the problem, there were other short devia- price per mile. -

Fort Leavenworth National Cemetery Lodge

HISTORIC AMERICAN LANDSCAPES SURVEY FORT LEAVENWORTH NATIONAL CEMETERY, LODGE HALS No. KS-1-A Location: 395 Biddle Boulevard, Leavenworth, Leavenworth County, Kansas. The coordinates for the Fort Leavenworth National Cemetery, Lodge are 94.888227 W and 39.275444 N, and they were obtained in August 2012 with, it is assumed, NAD 1983. There is no restriction on the release of the locational data to the public. Present Owner: National Cemetery Administration, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Prior to 1988, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs was known as the Veterans Administration. The Veterans Administration took over management of Fort Leavenworth National Cemetery from the U.S. Army in 1973 (Public Law 93-43). Date: 1904-05. Builder/Contractor: Unknown. Description: In 1905, the two-story, brick lodge replaced the nineteenth-century, Second Empire style stone lodge; it kept the L-shaped floor plan but raised the second floor – eliminating the mansard – and covered the whole with hipped roofs. A small, triple window dormer was cut into the roof on the southeast front elevation. The foundations of the lodge were stone and concrete and the roof was initially covered in slate. The window lintels and sills appear in early twentieth- century photographs to be made of stone, and the double-hung sash glazed with one-over-one lights. The chimneystack was constructed of brick and is visible above the roofline. There were twenty-six screens and twenty-three window shades in the building. Maintenance ledgers from the Veterans Administration for the cemetery supplied the 1905 construction date for the present lodge, and the ledgers listed a series of repairs undertaken in the 1920s to 1960s. -

Prairie Generals and Colonels at Cantonment Missouri and Fort Atkinson

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Prairie Generals and Colonels at Cantonment Missouri and Fort Atkinson Full Citation: Virgil Ney, “Prairie Generals and Colonels at Cantonment Missouri and Fort Atkinson,” Nebraska History 56 (1975): 51-76. URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1975Generals.pdf Date: 8/25/2015 Article Summary: This article presents the history of Fort Atkinson (at the present-day town of Fort Calhoun, Nebraska) as well as biographies of General Henry Atkinson and General Henry Leavenworth, commanders at the fort at different times between 1820 and 1827. Cataloging Information: Names: Henry Atkinson, Paul Wilhelm, James O Pattie, Marvin F Kivett, Gabriel H Manigault, George Izard, John C Calhoun, Jacob Brown, Mary Ann Bulitt, Edward Graham Atkinson, Benjamin W Atkinson, Alexander Macomb, Henry Leavenworth, Henry Dodge, Stephen W Kearny, Elizabeth Eunice