A Tale of Two Rivers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S T a T E O F N E W Y O R K 3695--A 2009-2010

S T A T E O F N E W Y O R K ________________________________________________________________________ 3695--A 2009-2010 Regular Sessions I N A S S E M B L Y January 28, 2009 ___________ Introduced by M. of A. ENGLEBRIGHT -- Multi-Sponsored by -- M. of A. KOON, McENENY -- read once and referred to the Committee on Tourism, Arts and Sports Development -- recommitted to the Committee on Tour- ism, Arts and Sports Development in accordance with Assembly Rule 3, sec. 2 -- committee discharged, bill amended, ordered reprinted as amended and recommitted to said committee AN ACT to amend the parks, recreation and historic preservation law, in relation to the protection and management of the state park system THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK, REPRESENTED IN SENATE AND ASSEM- BLY, DO ENACT AS FOLLOWS: 1 Section 1. Legislative findings and purpose. The legislature finds the 2 New York state parks, and natural and cultural lands under state manage- 3 ment which began with the Niagara Reservation in 1885 embrace unique, 4 superlative and significant resources. They constitute a major source of 5 pride, inspiration and enjoyment of the people of the state, and have 6 gained international recognition and acclaim. 7 Establishment of the State Council of Parks by the legislature in 1924 8 was an act that created the first unified state parks system in the 9 country. By this act and other means the legislature and the people of 10 the state have repeatedly expressed their desire that the natural and 11 cultural state park resources of the state be accorded the highest 12 degree of protection. -

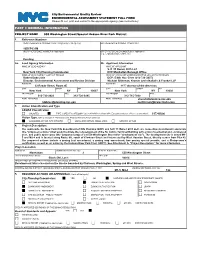

550 Washington Street/Special Hudson River Park District 1

City Environmental Quality Review ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT STATEMENT FULL FORM Please fill out, print and submit to the appropriate agency (see instructions) PART I: GENERAL INFORMATION PROJECT NAME 550 Washington Street/Special Hudson River Park District 1. Reference Numbers CEQR REFERENCE NUMBER (To Be Assigned by Lead Agency) BSA REFERENCE NUMBER (If Applicable) 16DCP031M ULURP REFERENCE NUMBER (If Applicable) OTHER REFERENCE NUMBER(S) (If Applicable) (e.g., Legislative Intro, CAPA, etc.) Pending 2a. Lead Agency Information 2b. Applicant Information NAME OF LEAD AGENCY NAME OF APPLICANT SJC 33 Owner 2015 LLC New York City Planning Commission DCP Manhattan Borough Office NAME OF LEAD AGENCY CONTACT PERSON NAME OF APPLICANT’S REPRESENTATIVE OR CONTACT PERSON Robert Dobruskin DCP: Edith Hsu-Chen (212-720-3437) Director, Environmental Assessment and Review Division Michael Sillerman, Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel LLP ADDRESS ADDRESS 22 Reade Street, Room 4E 1177 Avenue of the Americas CITY STATE ZIP CITY STATE ZIP New York NY 10007 New York NY 10036 TELEPHONE FAX TELEPHONE FAX 212-720-3423 212-720-3495 212-715-7838 EMAIL ADDRESS EMAIL ADDRESS [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 3. Action Classification and Type SEQRA Classification UNLISTED TYPE I; SPECIFY CATEGORY (see 6 NYCRR 617.4 and NYC Executive Order 91 of 1977, as amended): 617.4(6)(v) Action Type (refer to Chapter 2, “Establishing the Analysis Framework” for guidance) LOCALIZED ACTION, SITE SPECIFIC LOCALIZED ACTION, SMALL AREA GENERIC ACTION 4. Project Description: The applicants, the New York City Department of City Planning (DCP) and SJC 33 Owner 2015 LLC, are requesting discretionary approvals (the “proposed actions”) that would facilitate the redevelopment of the St. -

July 8 Grants Press Release

CITY PARKS FOUNDATION ANNOUNCES 109 GRANTS THROUGH NYC GREEN RELIEF & RECOVERY FUND AND GREEN / ARTS LIVE NYC GRANT APPLICATION NOW OPEN FOR PARK VOLUNTEER GROUPS Funding Awarded For Maintenance and Stewardship of Parks by Nonprofit Organizations and For Free Live Performances in Parks, Plazas, and Gardens Across NYC July 8, 2021 - NEW YORK, NY - City Parks Foundation announced today the selection of 109 grants through two competitive funding opportunities - the NYC Green Relief & Recovery Fund and GREEN / ARTS LIVE NYC. More than ever before, New Yorkers have come to rely on parks and open spaces, the most fundamentally democratic and accessible of public resources. Parks are critical to our city’s recovery and reopening – offering fresh air, recreation, and creativity - and a crucial part of New York’s equitable economic recovery and environmental resilience. These grant programs will help to support artists in hosting free, public performances and programs in parks, plazas, and gardens across NYC, along with the nonprofit organizations that help maintain many of our city’s open spaces. Both grant programs are administered by City Parks Foundation. The NYC Green Relief & Recovery Fund will award nearly $2M via 64 grants to NYC-based small and medium-sized nonprofit organizations. Grants will help to support basic maintenance and operations within heavily-used parks and open spaces during a busy summer and fall with the city’s reopening. Notable projects supported by this fund include the Harlem Youth Gardener Program founded during summer 2020 through a collaboration between Friends of Morningside Park Inc., Friends of St. Nicholas Park, Marcus Garvey Park Alliance, & Jackie Robinson Park Conservancy to engage neighborhood youth ages 14-19 in paid horticulture along with the Bronx River Alliance’s EELS Youth Internship Program and Volunteer Program to invite thousands of Bronxites to participate in stewardship of the parks lining the river banks. -

Position Statement ESTABLISHING a NEIGHBORHOOD IMPROVEMENT

APA New York Metro Chapter 121 West 27th Street, Suite 705 New York, NY 10001 Attention: David Fields Phone: (646) 963-9229 Position Statement ESTABLISHING A NEIGHBORHOOD IMPROVEMENT DISTRICT for the HUDSON RIVER PARK The NY Metro Chapter of the American Planning Association is a professional, educational, and advocacy organization representing over 1,200 practicing planners and policy makers in New York City and its surrounding suburbs. We are part of a national association with a membership of 41,000 professionals and students who are engaged in programs and projects related to the physical, social and economic environment. In our role as a professional advocacy organization, we offer insights and recommendations on policy matters affecting issues such as housing, transportation and the environment. The Chapter has taken an interest in the proposal to form a Neighborhood Improvement District (NID) for the area surrounding the Hudson River Park. While we are generally in support of the proposal, we wish to point out a number of concerns we have with what appears to be an emerging trend of relying on alternative sources of funding for what should be a basic governmental responsibility. BACKGROUND The proposal for the NID was introduced by Friends of Hudson River Park, a private not- for-profit organization dedicated to raising funds for the “completion, care and enhancement” of the Park. Hudson River Park is a regional asset that not only serves the west side of Manhattan, but draws people from all around the metropolitan area. The creation of the Park led to a dramatic increase in property values along West Street, 10th, 11th & 12th Avenues and their intersecting streets. -

Take Advantage of Dog Park Fun That's Off the Chain(PDF)

TIPS +tails SEPTEMBER 2012 Take Advantage of Dog Park Fun That’s Off the Chain New York City’s many off-leash dog parks provide the perfect venue for a tail-wagging good time The start of fall is probably one of the most beautiful times to be outside in the City with your dog. Now that the dog days are wafting away on cooler breezes, it may be a great time to treat yourself and your pooch to a quality time dedicated to socializing, fun and freedom. Did you know New York City boasts more than 50 off-leash dog parks, each with its own charm and amenities ranging from nature trails to swimming pools? For a good time, keep this list of the top 25 handy and refer to it often. With it, you and your dog will never tire of a walk outside. 1. Carl Schurz Park Dog Run: East End Ave. between 12. Inwood Hill Park Dog Run: Dyckman St and Payson 24. Tompkins Square Park Dog Run: 1st Ave and Ave 84th and 89th St. Stroll along the East River after Ave. It’s a popular City park for both pooches and B between 7th and 10th. Soft mulch and fun times your pup mixes it up in two off-leash dog runs. pet owners, and there’s plenty of room to explore. await at this well-maintained off-leash park. 2. Central Park. Central Park is designated off-leash 13. J. Hood Wright Dog Run: Fort Washington & 25. Washington Square Park Dog Run: Washington for the hours of 9pm until 9am daily. -

Hudson Yards FGEIS

TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 8: Shadows ...............................................................................................8-1 A. INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................8-1 1. ISSUES.................................................................................................................................8-1 2. PRINCIPAL CONCLUSIONS...................................................................................................8-1 3. METHODOLOGY ..................................................................................................................8-2 4. MAXIMUM SHADOW STUDY AREA.....................................................................................8-3 5. CRITERIA AND REGULATIONS ............................................................................................8-3 6. DATA SOURCES ..................................................................................................................8-4 7. SCREENING AND DETAILED ANALYSIS METHODOLOGIES .................................................8-4 B. EXISTING CONDITIONS ....................................................................................................8-5 1. STUDY AREA ......................................................................................................................8-5 2. OTHER STUDY AREAS (CORONA YARD) ............................................................................8-5 3. OPEN SPACES – EXISTING CONDITIONS -

New York City Comprehensive Waterfront Plan

NEW YORK CITY CoMPREHENSWE WATERFRONT PLAN Reclaiming the City's Edge For Public Discussion Summer 1992 DAVID N. DINKINS, Mayor City of New lVrk RICHARD L. SCHAFFER, Director Department of City Planning NYC DCP 92-27 NEW YORK CITY COMPREHENSIVE WATERFRONT PLAN CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMA RY 1 INTRODUCTION: SETTING THE COURSE 1 2 PLANNING FRA MEWORK 5 HISTORICAL CONTEXT 5 LEGAL CONTEXT 7 REGULATORY CONTEXT 10 3 THE NATURAL WATERFRONT 17 WATERFRONT RESOURCES AND THEIR SIGNIFICANCE 17 Wetlands 18 Significant Coastal Habitats 21 Beaches and Coastal Erosion Areas 22 Water Quality 26 THE PLAN FOR THE NATURAL WATERFRONT 33 Citywide Strategy 33 Special Natural Waterfront Areas 35 4 THE PUBLIC WATERFRONT 51 THE EXISTING PUBLIC WATERFRONT 52 THE ACCESSIBLE WATERFRONT: ISSUES AND OPPORTUNITIES 63 THE PLAN FOR THE PUBLIC WATERFRONT 70 Regulatory Strategy 70 Public Access Opportunities 71 5 THE WORKING WATERFRONT 83 HISTORY 83 THE WORKING WATERFRONT TODAY 85 WORKING WATERFRONT ISSUES 101 THE PLAN FOR THE WORKING WATERFRONT 106 Designation Significant Maritime and Industrial Areas 107 JFK and LaGuardia Airport Areas 114 Citywide Strategy fo r the Wo rking Waterfront 115 6 THE REDEVELOPING WATER FRONT 119 THE REDEVELOPING WATERFRONT TODAY 119 THE IMPORTANCE OF REDEVELOPMENT 122 WATERFRONT DEVELOPMENT ISSUES 125 REDEVELOPMENT CRITERIA 127 THE PLAN FOR THE REDEVELOPING WATERFRONT 128 7 WATER FRONT ZONING PROPOSAL 145 WATERFRONT AREA 146 ZONING LOTS 147 CALCULATING FLOOR AREA ON WATERFRONTAGE loTS 148 DEFINITION OF WATER DEPENDENT & WATERFRONT ENHANCING USES -

2015 State Council of Parks Annual Report

2015 ANNUAL REPORT New York State Council of Parks, Recreation & Historic Preservation Seneca Art & Culture Center at Ganondagan State Historic Site Franklin D. Roosevelt State Park Governor Andrew M. Cuomo at Minnewaska State Park, site of new Gateway to the park. Letchworth State Park Nature Center groundbreaking Table of Contents Letter from the Chair 1 Priorities for 2016 5 NYS Parks and Historic Sites Overview 7 State Council of Parks Members 9 2016-17 FY Budget Recommendations 11 Partners & Programs 12 Annual Highlights 14 State Board for Historic Preservation 20 Division of Law Enforcement 22 Statewide Stewardship Initiatives 23 Friends Groups 25 Taughannock Falls State Park Table of Contents ANDREW M. CUOMO ROSE HARVEY LUCY R. WALETZKY, M.D. Governor Commissioner State Council Chair The Honorable Andrew M. Cuomo Governor Executive Chamber February 2016 Albany, NY 12224 Dear Governor Cuomo, The State Council of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation is pleased to submit its 2015 Annual Report. This report highlights the State Council of Parks and the Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation’s achievements during 2015, and sets forth recommendations for the coming year. First, we continue to be enormously inspired by your unprecedented capital investment in New York state parks, which has resulted in a renaissance of the system. With a total of $521 million invested in capital projects over the last four years, we are restoring public amenities, fixing failing infrastructure, creating new trails, and bringing our state’s flagship parks back to life. New Yorkers and tourists are rediscovering state parks, and the agency continues to plan for the future based on your commitment to provide a total of $900 million in capital funds as part of the NY Parks 2020 initiative announced in your 2015 Opportunity Agenda. -

Youth Guide to the Department of Youth and Community Development Will Be Updating This Guide Regularly

NYC2015 Youth Guide to The Department of Youth and Community Development will be updating this guide regularly. Please check back with us to see the latest additions. Have a safe and fun Summer! For additional information please call Youth Connect at 1.800.246.4646 T H E C I T Y O F N EW Y O RK O FFI CE O F T H E M AYOR N EW Y O RK , NY 10007 Summer 2015 Dear Friends: I am delighted to share with you the 2015 edition of the New York City Youth Guide to Summer Fun. There is no season quite like summer in the City! Across the five boroughs, there are endless opportunities for creation, relaxation and learning, and thanks to the efforts of the Department of Youth and Community Development and its partners, this guide will help neighbors and visitors from all walks of life savor the full flavor of the city and plan their family’s fun in the sun. Whether hitting the beach or watching an outdoor movie, dancing under the stars or enjoying a puppet show, exploring the zoo or sketching the skyline, attending library read-alouds or playing chess, New Yorkers are sure to make lasting memories this July and August as they discover a newfound appreciation for their diverse and vibrant home. My administration is committed to ensuring that all 8.5 million New Yorkers can enjoy and contribute to the creative energy of our city. This terrific resource not only helps us achieve that important goal, but also sustains our status as a hub of culture and entertainment. -

Nyc's Waterfront Parks

NYC’S WATERFRONT PARKS Does Central Park make you think: ―Been there. Done that?‖ Then head to the waterfront. Even New Yorkers are just discovering some of these new green getaways. And with those helpful city bike lanes, doing a tour from one to the next is a great full-day outing, with one-way bike rentals available at key spots along the route. If biking isn’t your thing just hit the park to walk, kayak, watch stunning sunsets, or try to catch a free event from spring to fall. The Hudson River Park This five-mile greenway park hugs the Hudson River from 59th Street to Battery Park. Although the park has a unified design, it’s divided into seven distinct sections that reflect the different neighborhood just across the Westside Highway. The star attraction here—especially for kids—is the Intrepid Sea, Air, and Space Museum at Pier 86 across from 46th Street. A few blocks south, The Circle Line and World Yacht offer boat tours of the Hudson. At piers 96 and 40, The Downtown Boat House (downtownboathouse.org) offers free kayaking. A classic summer experience is the free outdoor movies with popcorn are shown on Wednesday and Friday nights at Pier 54. Chelsea Piers, the mammoth sports center between piers 59 and 61 offers bowling, a driving range, ice skating, even trapeze classes. At Pier 66 Boathouse, you can take a two-hour $60 introductory sailing course with Hudson River Community Sailing (hudsonsailing.org) The park also sponsors free tours and classes including free fishing. -

MEETING of the BOARD of DIRECTORS December 6, 2018 at 4:00 Pm Spector Hall, 22 Reade Street New York, New York 10007

MEETING OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS December 6, 2018 at 4:00 pm Spector Hall, 22 Reade Street New York, New York 10007 MINUTES Directors Present: Diana L. Taylor, Chair Purnima Kapur Jeffrey Kaplan Alyssa Cobb-Konan for NYC Parks Department Douglas Durst Leslie Wright for NYS Office of Parks, Recreation & Historic Preservation Thomas Berkman for NYS Department of Environmental Conservation Jon Halpern Pamela Frederick Appearances: For the Hudson River Park Trust: Madelyn Wils, CEO and President Daniel Kurtz, CFO and Executive Vice President, Finance & Real Estate Noreen Doyle, Executive Vice President Christine Fazio, General Counsel Nicole Cuttino, Deputy General Counsel Also present: Connie Fishman, Hudson River Park Friends Dan Miller, Hudson River Park Advisory Council The Press The Public 1 With a quorum being present Chair Diana L. Taylor called the meeting to order at 4:06 p.m. Chair Taylor noted that all the member of the Board of Directors (the “Directors” or the “Board”) of the Hudson River Park Trust (the “Trust”) had received the Board meeting materials in advance and may ask questions or give comments in reference to the items on the agenda. Chair Taylor instructed the audience that questions or comments from the audience would not be entertained. Chair Taylor welcomed the newest member to the Board: Purnima Kapur. The Board welcomed Purnima. Next Chair Taylor directed attention to the first item on the agenda, which was the approval of the minutes of the September 26, 2018 meeting of the Board of Directors. There being no questions, upon a properly called motion, the following resolution passed unanimously. -

Aroundmanhattan

Trump SoHo Hotel South Cove Statue of Liberty 3rd Avenue Peter J. Sharp Boat House Riverbank State Park Chelsea Piers One Madison Park Four Freedoms Park Eastwood Time Warner Center Butler Rogers Baskett Handel Architects and Mary Miss, Stanton Eckstut, F A Bartholdi, Richard M Hunt, 8 Spruce Street Rotation Bridge Robert A.M. Stern & Dattner Architects and 1 14 27 40 53 66 Cetra Ruddy 79 Louis Kahn 92 Sert, Jackson, & Assocs. 105 118 131 144 Skidmore, Owings & Merrill Marner Architecture Rockwell Group Susan Child Gustave Eiffel Frank Gehry Thomas C. Clark Armand LeGardeur Abel Bainnson Butz 23 East 22nd Street Roosevelt Island 510 Main St. Columbus Circle Warren & Wetmore 246 Spring Street Battery Park City Liberty Island 135th St Bronx to E 129th 555 W 218th Street Hudson River -137th to 145 Sts 100 Eleventh Avenue Zucotti Park/ Battery Park & East River Waterfront Queens West / NY Presbyterian Hospital Gould Memorial Library & IRT Powerhouse (Con Ed) Travelers Group Waterside 2009 Addition: Pei Cobb Freed Park Avenue Bridge West Harlem Piers Park Jean Nouvel with Occupy Wall St Castle Clinton SHoP Architects, Ken Smith Hunters Point South Hall of Fame McKim Mead & White 2 15 Kohn Pedersen Fox 28 41 54 67 Davis, Brody & Assocs. 80 93 and Ballinger 106 Albert Pancoast Boiler 119 132 Barbara Wilks, Archipelago 145 Beyer Blinder Belle Cooper, Robertson & Partners Battery Park Battery Maritime Building to Pelli, Arquitectonica, SHoP, McKim, Mead, & White W 58th - 59th St 388 Greenwich Street FDR Drive between East 25th & 525 E. 68th Street connects Bronx to Park Ave W127th St & the Hudson River 100 11th Avenue Rutgers Slip 30th Streets Gantry Plaza Park Bronx Community College on Eleventh Avenue IAC Headquarters Holland Tunnel World Trade Center Site Whitehall Building Hospital for Riverbend Houses Brooklyn Bridge Park Citicorp Building Queens River House Kingsbridge Veterans Grant’s Tomb Hearst Tower Frank Gehry, Adamson Ventilation Towers Daniel Libeskind, Norman Foster, Henry Hardenbergh and Special Surgery Davis, Brody & Assocs.