Development and Displacement in the Damodar Valley of India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Indian Subcontinent

Johnsingh, A. J. T., Pandav, B., and Madhusudan, M. D. (2010). Status and Conservation of Tigers in the Indian Subcontinent. In Tigers of The World, Second Edition: 315-330: Elsevier Inc. Keywords: 4IN/baseline information/conservation/landscape/Panthera tigris/population size/range/status/tiger Abstract: Today, confined to less than 7% of their original range, tigers are going through one of the worst crises in their evolutionary history. The Indian subcontinent, which contains most of the world's wild tigers, represents only 11% of the world's tiger habitat. We estimate that there may be less than 1,600 tigers in the whole of the Indian subcontinent and the realistic maximum number of tigers that could be supported with its current habitat would be around 3,700. Tiger conservation in the Indian subcontinent faces a range of serious and complex threats, but we believe that most of these issues are still possible to address; India showed that this was possible in the 1970s when the survival of the tiger in the country also looked bleak. Here, we summarize some of the most important issues and suggest some means by which these may be addressed to secure the future of this majestic big cat. CHAPTER 24 Status and Conservation of Tigers in the Indian Subcontinent A.J.T. Johnsingh1, Bivash Pandav2, and M.D. Madhusudan1 1Nature Conservation Foundation, Mysore, Karnataka, India 2Tiger and Other Asian Big Cats Program, WWF-International, Kathmandu, Nepal OUT L I N E The Tiger in the Indian Subcontinent 316 Landscapes Likely to Support 50–100 Tigers 323 Present Tiger Range and Population Landscapes Likely to Support Estimates in the Subcontinent 316 50 Tigers 324 Existing Baseline Information for Tiger Discussion and Conservation 317 Recommendations 325 Landscapes for Tiger Conservation in Glimpses of Hope 327 the Indian Subcontinent 318 Landscapes Likely to Support Acknowledgments 328 at Least 200 Tigers 318 References 328 Landscapes Likely to Support 100–200 Tigers 322 Tigers of the World, Second Edition 315 © 20102009 Elsevier Inc. -

River Action Plan Damodar

ACTION PLAN FOR REJUVENATION OF DAMODAR RIVER IN JHARKHAND JHARKHAND STATE POLLUTION CONTROL BOARD, DHURWA, RANCHI, JHARKHAND-834004 CONTENT CHAPTER I ❖ BACKGROUND ❖ INTRODUCTION ❖ PHYSIOGRAPHY ❖ WATER RESOURCES & RAINFALL ❖ ANNUAL RAINFALL ❖ DEVIATION OF RAINFALL ❖ SEASONAL RAINFALL ❖ RAINFALL TREND IN RABI SEASON ❖ AVERAGE MOTHLY RAINFALL ❖ MOVING AVERAGE OF THE RAINFALL ❖ EXTREME EVENT ANALYSIS ❖ SURFACE WATER RESOURCES ❖ GROUND WATER RESOURCES ❖ DRAINAGE SYSTEM AND MAPS CHAPTER II DAMODAR RIVER BASIN RIVER COURSE AND MAJOR TRIBUTARIES CHAPTER III- SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE ❖ WATER RESOURCES AND ITS USES ❖ MINING AND INDUSTRIAL ACTIVITIES ❖ NATURAL AND ANTHROPOGENIC HAZARDS ❖ IDENTIFIED STRETCHES FOR REDUCING POLLUTION CHAPTER IV- ACTION PLAN ❖ ACTION PLAN- SHORT TERM AND LONG TERM ACTION AND THE IDENTIFIED AUTHORITIES FOR INITIATING ACTIONS AND THE TIME LIMITS FOR ENSURING COMPLIANCE ❖ SHORT TERM AND LONG TERM ACTION PLANS FOR REJUVENATION OF RIVERS AND THE IMPLEMENTING AGENCIES RESPONSIBLE FOR EXECUTION OF THE ACTION PLANS AND THE TIME LIMITS ARE GIVEN IN TABLE AS BELOW ❖ PROPOSED ACTION PLAN BY VARIOUS DEPARTMENT OF GOVT. OF JHARKHAND ❖ PROPOSED ACTION PLAN FOR RESTORATION OF JHARKHAND RIVERS ❖ ACTION PLAN AT VILLAGE LEVEL ❖ TIMELINES FOR IMPLEMENTATION OF MODEL RESTORATION PLAN in 2019- 2020 and 2020-2021 Chapter-1 JHARKHAND & ITS WATER RESOURCES 1.1 BACKGROUND:-Hon’ble National Green Tribunal passed the following orders in OA No. 673/2018 & M.A. No. 1777/2018 titled News item published in “The Hindu “authored by Shri Jacob Koshy titled “More river stretches are now critically polluted: CPCB on 20.09.2018 as per excerpts below. “The issue taken up for consideration in this matter is abatement of pollution in 351 river stretches in the country, identified as such by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB). -

Access Jharkhand-Obj07-04-2021-E-Book

Index 01. Jharkhand Special Branch Constable (Close 16. JSSC Assistant Competitive Examination Cadre) Competitive Exam 01-09-2019 28.06.2015. 02. J.S.S.C. - Jharkhand Excise Constable Exam 17. Jharkhand Forest Guard Appointment Com- 04-08-2019 petitive (Prelims) Exam - 24.05.2015. 03. SSC IS (CKHT)-2017, Intermediate Level (For 18. Jharkhand Staff Selection Commission the post of Hindi Typing Noncommittee in Com- organized Women Supervisor competitive puter Knowledge and Computer) Joint Competi- Exam - 2014. tive Exam 19. Fifth Combined Civil Service Prelims Compet- 04. JUVNL Office Assistent Exam 10-03-2017 itive Exam - 15.12.2013. 05. J.S.S.C. - Post Graduate Exam 19-02-2017 20. Jharkhand Joint Secretariat Assistant (Mains) 06. J.S.S.C Amin Civil Resional Investigator Exam Examination 16.12.2012. 08-01-2017 21. State High School Teacher Appointment 07. JPSC Prelims Paper II (18.12.2016) Examination 29.08.2012. 08. JPSC Prelims Paper-I (Jharkhand Related 22. Jharkhand Limited Departmental Exam- Questions Only on 18.12.2016) 2012. 09. Combined Graduation Standard Competitive 23. Jharkhand Joint Secretariat Assistant Exam- (Prelims) Examinations 21.08.2016 2012. 10. Kakshpal appointment (mains) Competitive 24. Fourth Combined Civil Service (Prelims) Examination 10.07.2016. Competitive Examination - 2010. 11. Jharkhand Forest guard appointment (mains) 25. Government High School Teacher Appoint- Competitive Examination 16.05.2016. ment Exam - 2009. 12. JSSC Kakshpal Competitive (Prelims) Exam - 26. Primary Teacher Appointment Exam - 2008. 20.03.2016. 27. Third Combined Civil Service Prelims 13. Jharkhand Police Competitive Examination Competitive Exam - 2008. 30.01.2016. 28. JPSC Subsidiary Examination - 2007. -

The Plateau and the Desert Region

The Plateau and the Desert Region Question Answers Q1.Why are the rivers of the Deccan Plateau not perennial? Ans: The rivers of the Deccan Plateau are rain fed.The water in the rivers is full in rainy season and they dry up in summer season. So these rivers are not perennial rivers. Q2. Why do many rivers of the plateau region flow from west towards east? Ans: Many rivers of the plateau region flow from west towards east because the plateau is higher in the west and slopes towards the east. The Deccan Plateau Q4.From which word has the term ‘Deccan ‘ come? Ans: The term ‘Deccan’ come from the Sanskrit word ‘dakshin’ which means south. Q6. Which is the highest water falls in India? Ans:The Jog Falls on the Sharavathi river in Karnataka is the highest water falls in India. Parts of the Central Highlands Q3. Name the two parts of the Central Highlands? Ans: The two parts of the Central Highlands are the Malwa Plateau and the Chota Nagpur Plateau. Q4. Name the important minerals found in the Chota Nagpur Plateau. Ans: The important minerals found in the Chota Nagpur Plateau are coal, iron ore manganese , copper, mica. ASSIGNMENT Fill in the blanks 1.The river Narmada divides the Southern Plateau into the ___________ and the ___________ 2.The Deccan Plateau is ____________in shape. 3. Cotton grows well in ____________soil. 4. The Jog Falls is on the river ___________. 5. The __________ river is also known as Ganga of the south. 6.The Chota Nagpur Plateau has rich deposits of ___________. -

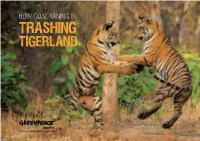

How Coal Mining Is Trashing Tigerland

Author Contact Ashish Fernandes Ashish Fernandes [email protected] Research coordination & North Karanpura case study Nandikesh Sivalingam Kanchi Kohli [email protected] Research Photo Editor Aishwarya Madineni, Vikal Samdariya, Arundhati Sudhanshu Malhotra Muthu and Preethi Herman Design GIS Analysis Aditi Bahri Ecoinformatics Lab, ATREE (Kiran M.C., Madhura Cover image Niphadkar, Aneesh A., Pranita Sambhus) © Harshad Barve / Greenpeace Acknowledgments Image Sudiep Shrivastava for detailed inputs on the Forests of Sanjay Dubri Tiger Hasdeo-Arand and Mandraigarh sections, Kishor Reserve near Singrauli coalfield Rithe for inputs on the Wardha and Kamptee © Dhritiman Mukherjee / Greenpeace sections, Bulu Imam and Justin Imam for their expertise on the North Karanpura section, Biswajit Printed on 100% recycled paper. Mohanty for feedback on the Talcher and Ib Valley sections and Belinda Wright for feedback on the Sohagpur and Singrauli sections. CONTENTS Executive Summary 01 9. Hasdeo-Arand (Chhattisgarh) 51 10. West Bokaro (Jharkhand) 55 Introduction 09 Central India,Tigers, Corridors and Coal 11. North Karanpura (Jharkhand) 60 How Coal is Trashing Tigerland 17 Case Study I 63 The North Karanpura Valley - On the edge Methodology 21 12. Wardha (Maharashtra) 00 Coalfield Analysis 25 13. Kamptee (Maharashtra) 00 1. Singrauli (Madhya Pradesh - Chhattisgarh) 27 Case Study II 87 2. Sohagpur (Madhya Pradesh - Chhattisgarh) 33 Chandrapur’s tigers - Encircled by coal 3. Sonhat (Chhattisgarh) 35 4. Tatapani (Chhattisgarh) 37 Alternatives: Efficiency and Renewables 101 5. Auranga (Jharkhand) 39 References 109 6. Talcher (Odisha) 41 Glossary 7. Ib Valley (Odisha) 47 110 8. Mandraigarh (Chhattisgarh) 49 Endnotes 111 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY As India’s national animal, the Royal Bengal Tiger Panthera tigris has ostensibly been a conservation priority for current and past governments. -

Comparative Physiography of the Lower Ganges and Lower Mississippi Valleys

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1955 Comparative Physiography of the Lower Ganges and Lower Mississippi Valleys. S. Ali ibne hamid Rizvi Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Rizvi, S. Ali ibne hamid, "Comparative Physiography of the Lower Ganges and Lower Mississippi Valleys." (1955). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 109. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/109 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMPARATIVE PHYSIOGRAPHY OF THE LOWER GANGES AND LOWER MISSISSIPPI VALLEYS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography ^ by 9. Ali IJt**Hr Rizvi B*. A., Muslim University, l9Mf M. A*, Muslim University, 191*6 M. A., Muslim University, 191*6 May, 1955 EXAMINATION AND THESIS REPORT Candidate: ^ A li X. H. R iz v i Major Field: G eography Title of Thesis: Comparison Between Lower Mississippi and Lower Ganges* Brahmaputra Valleys Approved: Major Prj for And Chairman Dean of Gri ualc School EXAMINING COMMITTEE: 2m ----------- - m t o R ^ / q Date of Examination: ACKNOWLEDGMENT The author wishes to tender his sincere gratitude to Dr. Richard J. Russell for his direction and supervision of the work at every stage; to Dr. -

Kolkata Rising

MYSTIC EAST ...an unexplored horizon A bi-monthly magazine by HRAEI | Vol 4 | Issue 6 | November - December 2018 Holiday Inn Resort Kolkata NH6 KOLKATA RISING Two brand new properties make their debut in the city as Kolkata registers a positive RevPar and a hopping 72 per cent occupancy, Zone by the Park, Kolkata says survey DIRECTOR'S NOTE Kolkata, clocked the highest increase in supply in the major markets across the country, compared to the previous fiscal. In the 2018 Indian Hospitality Trends and the hotels located in Salt Lake City, Rajarhat IOpportunities report by Hotelivate, the East- and E.M Bypass. ern India, specifically Kolkata, has clocked the highest increase in supply in the major Over 20 per cent increase in supply has been markets across the country, compared to the attributed to sporting events, economic previous fiscal. and infrastructural growth, rising air traffic and the advent of submarkets – which has The city witnessed its first positive RevPAR aided the absorption of a significantly faster growth of approximately 3 per cent in four supply. The report forecasts that Kolkata years in 2017/18, registering an estimated would continue to witness a healthy growth occupancy of 72 per cent and an average in occupancies in the near term. rate of about Rs 6,100. More specifically, the two micro-markets of the city demonstrated This is not surprising as the city has been in varying operating performance owing to the process of re-inventing itself in the past their unique characteristics of supply and decade. Kolkata possesses several attributes demand. -

Chota Nagpur

hropolo nt gy A Gautam, Anthropol 2017, 5:2 Anthropology DOI: 10.4172/2332-0915.1000180 ISSN: 2332-0915 Research Article Article Open Access Chota Nagpur - An Untold History: A Socio-Historical Analysis Ambrish Gautam* Centre for Sociological Studies, School of Social Science and Policy, Central University of South Bihar, Gaya, India Abstract It is customary with historians to divide the history of a country into the historic and the pre historic periods. The historic period of India has been dated to be the seventh century B.C. by Dr. V. Smith, apparently rejecting the earlier events on the ground that no fixed dates can be assigned to them. On the same principle, the historical period of Chota Nagpur will be dated from the later part of the 16th century A.D., when in the 30th regnal year of Emperor Akbar’s reign, i.e., 1585 A.D. a detachment was sent to Chota Nagpur under Shahbaz Khan Kambu; while the excessively date-minded scholars would prefer to begin regular history of this plateau from the year 1765, when the Diwani of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa was conferred upon the East India Company. Indus Valley and Chotanagpur: Sir John Marshall, while dealing with the extent of the Indus civilization eastward does not seem to have taken into his consideration the pre-historic relics of Chota Nagpur, discovered between the years 1915 and 1920, and published in the Journal of the B and O Research Society by Rai Bahadur Roy. The late learned Director-General of Archaeology in India, however, admits that no effort has yet been made to trace the Indus valley civilization eastward. -

Class -4Th Social Science Lesson- 6 the Peninsular Plateau Meaning Of

Class -4th Social science Lesson- 6 The Peninsular plateau Meaning of Plateau – An area of land that rises high but is flat on to is called a plateau . The Peninsular plateau includes – ❖ The central Highlands ❖ The Deccan plateau Central Highlands – It includes Malwa plateau in the north -west and the Chota Nagpur plateau in the north - east . The river originating in the central Highlands are – the Chambal , Betwa and Son . The Malwa plateau – The Malwa plateau stretches across Rajasthan , Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat . It is bounded by the Aravelli Hills in the north-west and the Vindhya and Satpura hills in the south . Fine black soil of this region is ideal for growing cotton and oilseeds. The Chota Nagpur plateau – It lies in the eastern part of India . It covers the states of Jharkhand and adjacent parts of Odisha , Bihar and chattisgarh . This region gets good amount of rainfall and is thickly forested . The area also has good deposits of coal , iron-ore , manganese , bauxite ,mica and other minerals . The Deccan plateau – It is the largest plateau in India . It is bounded by the Western Ghats in the west and the Eastern Ghats in the east . The states which lie in the Deccan plateau are Gujarat , Maharashtra , Madhya Pradesh , chattisgarh, Odisha, Jharkhand , Telengana , Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka , Tamil Nadu and eastern part of Kerala . This plateau is drained by rivers – Mahanadi ,Godavari ,Krishna and Kaveri . The Deccan plateau has many waterfalls . The most famous of them is the Jog Falls on the river Sharavati in Karnataka . It is the highest waterfall in India . -

JCPSICE-2017 Set04 APTITUDE

JCPSICE-2017 Set04 APTITUDE Topic:- JSSC_SI_Set4_Apt_CK 1) ____________ a table means making changes in the table by inserting rows or columns or deleting unwanted rows or columns. ______ का अथ है, पंयो ं या ंभो ं को जोड़ना या अवांिछत पंयो ं या ंभो ं को हटा कर तािलका म परवतन करना| [Question ID = 4899] 1. Modifying / संशोिधत करना [Option ID = 19613] 2. Inserting /सिलत करना [Option ID = 19614] 3. Deleting /हटा देना [Option ID = 19615] 4. Copying / ितिलिप बनाना [Option ID = 19616] Correct Answer :- Modifying / संशोिधत करना [Option ID = 19613] 2) ____________cells is a way of combining data from separate cells into a single cell. ____ अलग-अलग सेल से डेटा को एक ही सेल म संयोिजत करने का एक तरीका है. [Question ID = 4900] 1. Delete / िमटाना [Option ID = 19617] 2. Undo / पूववत करना [Option ID = 19618] 3. Modify / परवितत करना [Option ID = 19619] 4. Merging / िवलय करना [Option ID = 19620] Correct Answer :- Merging / िवलय करना [Option ID = 19620] 3) For creating charts you can use the command called __________ चाट बनाने के िलए आप कमांड का इेमाल कर सकते ह िजसे _______कहा जाता है. [Question ID = 4901] 1. Pivot Table / पाइवट तािलका [Option ID = 19621] 2. PivotChart / पाइवट लेखािच [Option ID = 19622] 3. Data menu / डेटा मेू [Option ID = 19623] 4. Chart Wizard / चाट िवज़ड [Option ID = 19624] Correct Answer :- Chart Wizard / चाट िवज़ड [Option ID = 19624] 4) Cell address B$6 in a formula means it is a एक फॉमूला म,सेल एडेस बी$ 6 का अथ है िक यह है- [Question ID = 4902] 1. -

India and Graph Paper

MT 154 2013 .... .... 1100 Seat No. –MT 154 –SOCIAL SCIENCE (73) GEOGRAPHY & ECONOMICS– PRELIM I – PAPER II (E) Time : 2 Hours (Pages 3) Max. Marks : 40 Note : (i) All figures are compulsory. (ii) Figures to the right indicate full marks. (iii) Draw neat diagrams and sketches wherever necessary (iv) Use the supplied outline map of India and graph paper. (v) To draw map of India use of Stencil is allowed. Q.1. (A) Complete and write the following statements by choosing 3 appropriate alternative from the given in the brackets : (i) __________ is the most continuous, loftiest & northernmost range of Himalaya. (Shiwalik, Aravali, Himadri, Himachal) (ii) The triangular region to the south of Narmada is known as the __________ plateau. (Malwa, Bundelkhand, Chota Nagpur, Deccan) (iii) Most of the region is drained by small seasonal streams known as ____________ (Chos, Doab, river, tributary) Q.1. (B) Match the Columns : 3 Group ‘A’ Group ‘B’ (i) Agatti (a) Godavari Delta (ii) Eastern Coastal plain (b) Madhya Pradesh (iii) Vindhayanchal (c) Andaman and Nicobar islands (d) An airport Q.2. (A) Give geographical reasons : (Any 2) 4 (i) Punjab-Haryana plain has become a granary of India. (ii) North Indian mountain are home land to many tribals. (iii) Rural settlements in the peninsular part exhibit mixed types. Q.2. (B) Write short notes : (Any 2) 4 (i) Characteristics of the North India Plains. (ii) Physiography of Marusthali. (iii) Natural Vegetation in the Western Ghats 2 / MT - 154 Paper - II Q.3. (A) Draw a divided rectangle with the following information. 2 Mineral Ore Production in million tonnes Percentage Iron Ore 95.98 43 Manganese 43.68 20 Bauxite 18.24 8 Copper 32.48 14 Mica 33.00 15 Total 223.38 100 Q.3. -

Class Notes the Peninsular Plateau

Class Notes Class: IX Topic: Ch-2 Physical features of India (thePeninsular Plateau, the Indian Desert and the Subject: Geography Islands) The Peninsular plateau The Peninsular plateau is a tableland composed of the old crystalline, igneous and metamorphic rocks. It was formed due to the breaking and drifting of the Gondwana land and thus, making it a part of the oldest landmass. The plateau has broad and shallow valleys and rounded hills. This plateau consists of two broad divisions: Central Highlands Peninsular plateau lying to the north of the Narmada river is known as the Central Highlands. E.g Malwa Plateau The Vindhyan rangeis bounded by the Central Highlands on the south and the Aravalis on the northwest.The eastward extension of this plateau are Bundelkhand and Baghelkhand Deccan Plateau A triangular landmass that lies to the south of the river Narmada. The Satpura range flanks its broad base in the northwhile the Mahadev, the Kaimur hills and the Maikal range form its eastern extensions The Western Ghats and the Eastern Ghats mark the western and the eastern edges of the Deccan Plateau respectively. The Indian Desert The Great Indian Desert, also known as the Thar Desert, forms a natural boundary between India and Pakistan. It is the world's 17th largest desert.. Thar Desert is a large arid region in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent. About 85% of the Thar Desert is located within India, with the remaining 15% in Pakistan. More than 60% of the desert lies in the state of Rajasthan, and it extends into Sindh, Gujarat, Punjab, and Haryana.