South Carolina's Statewide Forest Resource Assessment and Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplementary Material Clariss Domin Drechs

CLARISSA ROSA et al. LONG TERM CONSERVATION IN BRAZIL SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Table SI. Location of sites of the Brazilian Program for Biodiversity Research network. Type id Latitude Longitude Site name CLARISSA ROSA, FABRICIO BACCARO, CECILIA CRONEMBERGER, JULIANA HIPÓLITO, CLAUDIA FRANCA BARROS, Module 1 -9.370 -69.9200 Chandless State Park DOMINGOS DE JESUS RODRIGUES, SELVINO NECKEL-OLIVEIRA, GERHARD E. OVERBECK, ELISANDRO RICARDO Running title: Long term Grid 2 1.010 -51.6500 Amapá National Forest DRECHSLER-SANTOS, MARCELO RODRIGUES DOS ANJOS, ÁTILLA C. FERREGUETTI, ALBERTO AKAMA, MARLÚCIA conservation in Brazil Module 3 -3.080 -59.9600 Federal University of Amazonas BONIFÁCIO MARTINS, WALFRIDO MORAES TOMAS, SANDRA APARECIDA SANTOS, VANDA LÚCIA FERREIRA, CATIA Grid 4 -2.940 -59.9600 Adolpho Ducke Forest Reserve NUNES DA CUNHA, JERRY PENHA, JOÃO BATISTA DE PINHO, SUZANA MARIA SALIS, CAROLINA RODRIGUES DA Academy Section: Ecosystems Module 5 -5.610 -67.6000 Médio Juruá COSTA DORIA, VALÉRIO D. PILLAR, LUCIANA R. PODGAISKI, MARCELO MENIN, NARCÍSIO COSTA BÍGIO, SUSAN Grid 6 -1.760 -61.6200 Jaú National Park ARAGÓN, ANGELO GILBERTO MANZATTO, EDUARDO VÉLEZ-MARTIN, ANA CAROLINA BORGES LINS E SILVA, THIAGO Module 7 -2.450 -59.7500 PDBFF fragments JUNQUEIRA IZZO, AMANDA FREDERICO MORTATI, LEANDRO LACERDA GIACOMIN, THAÍS ELIAS ALMEIDA, THIAGO e20201604 Grid 8 -1.780 -59.2700 Uatumã Biological Reserve ANDRÉ, MARIA AUREA PINHEIRO DE ALMEIDA SILVEIRA, ANTÔNIO LAFFAYETE PIRES DA SILVEIRA, MARILUCE Grid 9 -2.660 -60.0600 Experimental Farm from UFAM REZENDE MESSIAS, MARCIA C. M. MARQUES, ANDRE ANDRIAN PADIAL, RENATO MARQUES, YOUSZEF O.C. BITAR, 93 Grid 10 -3.030 -60.3700 Anavilhanas National Park MARCOS SILVEIRA, ELDER FERREIRA MORATO, RUBIANI DE CÁSSIA PAGOTTO, CHRISTINE STRUSSMANN, RICARDO (2) 93(2) Module 11 -3.090 -55.5200 BR-163 M08 BOMFIM MACHADO, LUDMILLA MOURA DE SOUZA AGUIAR, GERALDO WILSON FERNANDES YUMI OKI, SAMUEL Module 12 -4.080 -60.6700 Tupana NOVAIS, GUILHERME BRAGA FERREIRA, FLÁVIA RODRIGUES BARBOSA, ANA C. -

Executive Director – Upstate South Carolina REPORTS

Local Initiatives Support Corporation Position Description POSITION TITLE: Executive Director – Upstate South Carolina REPORTS TO: Executive Vice President, Programs LOCATION: Greenville, Spartanburg or Anderson, South Carolina JOB CLASSIFICATION: Full time/Exempt The Organization What We Do With residents and partners, LISC forges resilient and inclusive communities of opportunity across America – great places to live, work, visit, do business and raise families. Strategies We Pursue • Equip talent in underinvested communities with the skills and credentials to compete successfully for quality income and wealth opportunities. • Invest in businesses, housing and other community infrastructure to catalyze economic, health, safety and educational mobility for individuals and communities. • Strengthen existing alliances while building new collaborations to increase our impact on the progress of people and places. • Develop leadership and the capacity of partners to advance our work together • Drive local, regional, and national policy and system changes that foster broadly shared prosperity and well-being. Over the last 40 years, LISC and its affiliates have invested approximately $22 billion in businesses, affordable housing, health, educational mobility, community and recreational facilities, public safety, employment and other projects that help to revitalize and stabilize underinvested communities. Headquartered in New York City, LISC’s reach spans the country from East coast to West coast in 36 markets with offices extending from Buffalo to San Francisco. Visit us at www.lisc.org Summary LISC seeks an experienced leader to be the Executive Director in Upstate South Carolina to provide direction and guidance for all aspects of LISC’s programs in the region. This position will be guiding the introduction of LISC to the Upstate region of South Carolina, marketing and building the staff and programmatic work. -

Unali'yi Lodge

Unali’Yi Lodge 236 Table of Contents Letter for Our Lodge Chief ................................................................................................................................................. 7 Letter from the Editor ......................................................................................................................................................... 8 Local Parks and Camping ...................................................................................................................................... 9 James Island County Park ............................................................................................................................................... 10 Palmetto Island County Park ......................................................................................................................................... 12 Wannamaker County Park ............................................................................................................................................. 13 South Carolina State Parks ................................................................................................................................. 14 Aiken State Park ................................................................................................................................................................. 15 Andrew Jackson State Park ........................................................................................................................................... -

Land Areas of the National Forest System, As of September 30, 2019

United States Department of Agriculture Land Areas of the National Forest System As of September 30, 2019 Forest Service WO Lands FS-383 November 2019 Metric Equivalents When you know: Multiply by: To fnd: Inches (in) 2.54 Centimeters Feet (ft) 0.305 Meters Miles (mi) 1.609 Kilometers Acres (ac) 0.405 Hectares Square feet (ft2) 0.0929 Square meters Yards (yd) 0.914 Meters Square miles (mi2) 2.59 Square kilometers Pounds (lb) 0.454 Kilograms United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Land Areas of the WO, Lands National Forest FS-383 System November 2019 As of September 30, 2019 Published by: USDA Forest Service 1400 Independence Ave., SW Washington, DC 20250-0003 Website: https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar-index.shtml Cover Photo: Mt. Hood, Mt. Hood National Forest, Oregon Courtesy of: Susan Ruzicka USDA Forest Service WO Lands and Realty Management Statistics are current as of: 10/17/2019 The National Forest System (NFS) is comprised of: 154 National Forests 58 Purchase Units 20 National Grasslands 7 Land Utilization Projects 17 Research and Experimental Areas 28 Other Areas NFS lands are found in 43 States as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. TOTAL NFS ACRES = 192,994,068 NFS lands are organized into: 9 Forest Service Regions 112 Administrative Forest or Forest-level units 503 Ranger District or District-level units The Forest Service administers 149 Wild and Scenic Rivers in 23 States and 456 National Wilderness Areas in 39 States. The Forest Service also administers several other types of nationally designated -

Green Economy in Amapá State, Brazil Progress and Perspectives

Green economy in Amapá State, Brazil Progress and perspectives Virgilio Viana, Cecilia Viana, Ana Euler, Maryanne Grieg-Gran and Steve Bass Country Report Green economy Keywords: June 2014 green growth; green economy policy; environmental economics; participation; payments for environmental services About the author Virgilio Viana is Chief Executive of the Fundação Amazonas Sustentável (Sustainable Amazonas Foundation) and International Fellow of IIED Cecilia Viana is a consultant and a doctoral student at the Center for Sustainable Development, University of Brasília Ana Euler is President-Director of the Amapá State Forestry Institute and Researcher at Embrapa-AP Maryanne Grieg-Gran is Principal Researcher (Economics) at IIED Steve Bass is Head of IIED’s Sustainable Markets Group Acknowledgements We would like to thank the many participants at the two seminars on green economy in Amapá held in Macapá in March 2012 and March 2013, for their ideas and enthusiasm; the staff of the Fundação Amazonas Sustentável for organising the trip of Amapá government staff to Amazonas; and Laura Jenks of IIED for editorial and project management assistance. The work was made possible by financial support to IIED from UK Aid; however the opinions in this paper are not necessarily those of the UK Government. Produced by IIED’s Sustainable Markets Group The Sustainable Markets Group drives IIED’s efforts to ensure that markets contribute to positive social, environmental and economic outcomes. The group brings together IIED’s work on market governance, business models, market failure, consumption, investment and the economics of climate change. Published by IIED, June 2014 Virgilio Viana, Cecilia Viana, Ana Euler, Maryanne Grieg-Gran and Steve Bass. -

Concepts and Applications in Veterinary Toxicology an Interactive Guide Concepts and Applications in Veterinary Toxicology PK Gupta

PK Gupta Concepts and Applications in Veterinary Toxicology An Interactive Guide Concepts and Applications in Veterinary Toxicology PK Gupta Concepts and Applications in Veterinary Toxicology An Interactive Guide PK Gupta Toxicology Consulting Group Academy of Sciences for Animal Welfare Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh, India ISBN 978-3-030-22249-9 ISBN 978-3-030-22250-5 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22250-5 © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors, and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. This Springer imprint is published by the registered company Springer Nature Switzerland AG The registered company address is: Gewerbestrasse 11, 6330 Cham, Switzerland Preface The book entitled Concepts and Applications in Veterinary Toxicology: An Interactive Guide covers a broad spectrum of topics for the students specializing in veterinary toxicology and veterinary medical practitioners. -

Record of Decision (ROD)

U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY EPA REGION 1 – NEW ENGLAND RECORD OF DECISION NYANZA CHEMICAL WASTE DUMP SUPERFUND SITE OPERABLE UNIT 02 ASHLAND, MASSACHUSETTS JULY 2020 PART 1: THE DECLARATION FOR THE RECORD OF DECISION A. SITE NAME AND LOCATION B. STATEMENT OF BASIS AND PURPOSE C. ASSESSMENT OF SITE D. DESCRIPTION OF SELECTED REMEDY E. STATUTORY DETERMINATIONS F. SPECIAL FINDINGS G. DATA CERTIFICATION CHECKLIST H. AUTHORIZING SIGNATURES PART 2: THE DECISION SUMMARY A. SITE NAME, LOCATION, AND BRIEF DESCRIPTION B. SITE HISTORY AND ENFORCEMENT ACTIVITIES 1. History of Site Activities 2. History of Federal and State Investigations and Removal and Remedial Actions 3. History of CERCLA Enforcement Activities C. COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION D. SCOPE AND ROLE OF OPERABLE UNIT OR RESPONSE ACTION E. SITE CHARACTERISTICS F. CURRENT AND POTENTIAL FUTURE SITE AND RESOURCE USES G. SUMMARY OF SITE RISKS 1. Human Health Risk Assessment 2. Supplemental Human Health Risk Assessment 3. Supplemental Evaluation Following Risk Assessment 4. Ecological Risk Assessment 5. Basis for Remedial Action H. REMEDIAL ACTION OBJECTIVES I. DEVELOPMENT AND SCREENING OF ALTERNATIVES J. DESCRIPTION OF ALTERNATIVES K. SUMMARY OF COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF ALTERNATIVES L. THE SELECTED REMEDY M. STATUTORY DETERMINATIONS N. DOCUMENTATION OF NO SIGNIFICANT CHANGES O. STATE ROLE Record of Decision Nyanza Chemical Waste Dump Superfund Site: OU2 July 2020 Ashland, Massachusetts Page 2 of 73 PART 3: THE RESPONSIVENESS SUMMARY APPENDICES Appendix A: MassDEP Letter of Concurrence Appendix B: Tables Appendix C: Figures Appendix D: ARARs Tables Appendix E: References Appendix F: Acronyms and Abbreviations Appendix G: Administrative Record Index and Guidance Documents Record of Decision Nyanza Chemical Waste Dump Superfund Site: OU2 July 2020 Ashland, Massachusetts Page 3 of 73 PART 1: THE DECLARATION FOR THE RECORD OF DECISION A. -

Francis Marion and Sumter National Forests –Travel Analysis Report Page 2

Contents I. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................... 3 A. Objectives of Forest-Wide Transportation System Analysis Process (TAP) ...................................... 3 B. Analysis Participants and Process ..................................................................................................... 3 C. Overview of the Francis Marion National Forest Road System ........................................................ 5 D. Key Issues, Benefits, Problems and Risks, and Management Opportunities Identified ................... 5 E. Forest Plans and Roads ..................................................................................................................... 7 F. Comparison of Existing System to Maintained Road System as Proposed by the TAP .................. 10 II. Context ................................................................................................................................................ 10 A. Alignment with National and Regional Objectives ......................................................................... 10 B. Coordination with Forest Plan ........................................................................................................ 11 C. Budget and Political Realities .......................................................................................................... 11 D. 2012 Transportation Bill Effects (MAP-21) .................................................................................... -

S.C. Utility Demand-Side Management and System Overview 2006

S.C. Utility Demand-Side Management and System Overview 2006 A Report by the South Carolina Energy Office Division of Insurance and Grants Services State Budget and Control Board ________________________ S.C. Utility Demand-Side Management and System Overview, 2006 Published by the South Carolina Energy Office Division of Insurance and Grants Services State Budget and Control Board 1201 Main Street, Suite 430 Columbia, South Carolina 29201 August 2007 ______________________________________________________________________________________ ii S.C. Utility Demand-Side Management and System Overview, 2006 Table of Contents Executive Summary...........................................................................................................iv Definition of Terms used in this Report..............................................................................v The Status of Demand-Side Management Activities 2006 ................................................1 Introduction .............................................................................................................1 Background.............................................................................................................1 Categories of Demand-Side Management Activities...............................................2 Results and Findings .........................................................................................................3 Electricity ................................................................................................................3 -

South Carolina Forestry Commission

South Carolina Forestry Commission Fiscal Year 2011-2012 Annual Report South Carolina Forestry Commission Annual Report FY 2011-2012 The South Carolina Forestry Commission prohibits discrimination in all programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. The Forestry Commission is an equal opportunity provider and employer. To file a complaint of discrimination, contact the Human Resources Director, SC Forestry Commission, P.O. Box 21707, Columbia, SC 29221, or call (803) 896-8800. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREST PROTECTION 5 Fire Management 5 Forest Health 14 Equipment 16 Law Enforcement 17 FOREST MANAGEMENT 18 Forest Management Assistance 18 Forest Services 22 Forest Stewardship 23 Community Forestry 23 State Forests and other state lands 26 Harbison State Forest 26 Niederhof 27 Poe Creek 29 Manchester State Forest 31 Wee Tee State Forest 33 Sand Hills State Forest 34 State Lands Overview 38 Education 40 RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT 44 Business Development 44 Forest Inventory Analysis 45 Nursery and Tree Improvement 46 Environmental Management 52 TECHNOLOGY 53 Information Technology 53 GIS 53 Communications 54 Dispatch Operations 55 ADMINISTRATION 58 SCFC Financial Statement FY 2008-2009 58 Organizational Chart 59 2 STATE COMMISSION OF FORESTRY Members of the Commission Frank A. McLeod III, Columbia, Chair Mitchell S. Scott, Allendale, Vice Chair Dr. Benton H. Box, Clemson G. Edward Muckenfuss, Summerville H. Stro Morrison III, Estill Dr. A.G. “Skeet” Burris, Varnville James F. Barker, President, Clemson University Sam Coker, Gilbert James B. Thompson, Greenwood Administration Henry E. (Gene) Kodama, State Forester Joel T. -

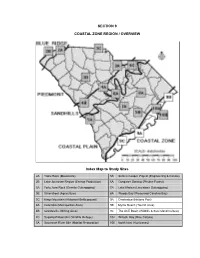

Coastal Zone Region / Overview

SECTION 9 COASTAL ZONE REGION / OVERVIEW Index Map to Study Sites 2A Table Rock (Mountains) 5B Santee Cooper Project (Engineering & Canals) 2B Lake Jocassee Region (Energy Production) 6A Congaree Swamp (Pristine Forest) 3A Forty Acre Rock (Granite Outcropping) 7A Lake Marion (Limestone Outcropping) 3B Silverstreet (Agriculture) 8A Woods Bay (Preserved Carolina Bay) 3C Kings Mountain (Historical Battleground) 9A Charleston (Historic Port) 4A Columbia (Metropolitan Area) 9B Myrtle Beach (Tourist Area) 4B Graniteville (Mining Area) 9C The ACE Basin (Wildlife & Sea Island Culture) 4C Sugarloaf Mountain (Wildlife Refuge) 10A Winyah Bay (Rice Culture) 5A Savannah River Site (Habitat Restoration) 10B North Inlet (Hurricanes) TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR SECTION 9 COASTAL ZONE REGION / OVERVIEW - Index Map to Coastal Zone Overview Study Sites - Table of Contents for Section 9 - Power Thinking Activity - "Turtle Trot" - Performance Objectives - Background Information - Description of Landforms, Drainage Patterns, and Geologic Processes p. 9-2 . - Characteristic Landforms of the Coastal Zone p. 9-2 . - Geographic Features of Special Interest p. 9-3 . - Carolina Grand Strand p. 9-3 . - Santee Delta p. 9-4 . - Sea Islands - Influence of Topography on Historical Events and Cultural Trends p. 9-5 . - Coastal Zone Attracts Settlers p. 9-5 . - Native American Coastal Cultures p. 9-5 . - Early Spanish Settlements p. 9-5 . - Establishment of Santa Elena p. 9-6 . - Charles Towne: First British Settlement p. 9-6 . - Eliza Lucas Pinckney Introduces Indigo p. 9-7 . - figure 9-1 - "Map of Colonial Agriculture" p. 9-8 . - Pirates: A Coastal Zone Legacy p. 9-9 . - Charleston Under Siege During the Civil War p. 9-9 . - The Battle of Port Royal Sound p. -

FDI in U.S. Metro Areas: the Geography of Jobs in Foreign- Owned Establishments

Global Cities Initiative A JOINT PROJECT OF BROOKINGS AND JPMORGAN CHASE FDI in U.S. Metro Areas: The Geography of Jobs in Foreign- Owned Establishments Devashree Saha, Kenan Fikri, and Nick Marchio Findings This paper advances the understanding of foreign direct investment (FDI)—that is to say, the U.S operations of foreign companies—in U.S. metro areas in three ways. First, it provides a framing of what FDI is and why it matters for the United States and its regions. Then it presents new data on jobs in foreign-owned establishments (FOEs) across the nation’s 100 largest metropolitan areas between 1991 and 2011. It concludes with a discussion of what policymakers and practitioners can “ The core tenets do to maximize the amount, quality, and economic benefits of FDI into the United States. The new data on the geography of jobs in FOEs forms the centerpiece of this report and of a good FDI reveals that: n Foreign-owned U.S. affiliates directly employ some 5.6 million workers spread across policy overlap every sector of the economy. The number and share of U.S. workers employed in FOEs increased steadily through the 1990s before peaking in 2000 and then stagnating. significantly with n The nation’s largest metro areas contain nearly three-quarters of all jobs in FOEs. Fully 74 percent of all jobs in FOEs are concentrated in the country’s 100 largest metro areas by popu- good economic lation, compared to 68 percent of total private employment. n FDI supports 5.5 percent of private employment in the average large metro area, with development significant regional variation.