My Autobiography and Reminiscences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G. Phd, Mphil, Dclinpsychol) at the University of Edinburgh

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Desire for Perpetuation: Fairy Writing and Re-creation of National Identity in the Narratives of Walter Scott, John Black, James Hogg and Andrew Lang Yuki Yoshino A Thesis Submitted to The University of Edinburgh for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Literature 2013 Abstract This thesis argues that ‘fairy writing’ in the nineteenth-century Scottish literature serves as a peculiar site which accommodates various, often ambiguous and subversive, responses to the processes of constructing new national identities occurring in, and outwith, post-union Scotland. It contends that a pathetic sense of loss, emptiness and absence, together with strong preoccupations with the land, and a desire to perpetuate the nation which has become state-less, commonly underpin the wide variety of fairy writings by Walter Scott, John Black, James Hogg and Andrew Lang. -

Fairy Elements in British Literary Writings in the Decade Following the Cottingley Fair Photographs Episode

Volume 32 Number 1 Article 2 10-15-2013 Fairy Elements in British Literary Writings in the Decade Following the Cottingley Fair Photographs Episode Douglas A. Anderson Independent Scholar Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, Douglas A. (2013) "Fairy Elements in British Literary Writings in the Decade Following the Cottingley Fair Photographs Episode," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 32 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol32/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Scholar Guest of Honor, Mythcon 2013. Explores the effects of the Cottingly fairy fraud on British literary fantasy. Authors discussed include Gerald Bullett, Walter de la Mare, Lord Dunsany, Bea Howe, Kenneth Ingram, Margaret Irwin, Daphne Miller, Hope Mirrlees, and Bernard Sleigh. -

Archived Press Release the Frick Collection

ARCHIVED PRESS RELEASE from THE FRICK COLLECTION 1 EAST 70TH STREET • NEW YORK • NEW YORK 10021 • TELEPHONE (212) 288-0700 • FAX (212) 628-4417 Victorian Fairy Painting OPENING AT THE FRICK COLLECTION, BRINGS NEW YORK AUDIENCES AN UNEXPECTED OPPORTUNITY TO EXPERIENCE THIS CRITICALLY ACCLAIMED EXHIBITION October 14, 1998 through January 17, 1999 Attracting record crowds in British and American venues, the exhibition Victorian Fairy Painting comes to The Frick Collection, extending its tour and offering New York audiences an unexpected opportunity to view this unique presentation. Victorian Fairy Painting, on view October 14, 1998 through January 17, 1999, represents the first comprehensive exhibition ever devoted to this distinctly British genre, which was critically and commercially popular from the early nineteenth century through the beginning of World War I. The paintings, works on paper, and objects, approximately thirty four in number, have been selected by Edgar Munhall, Curator of The Frick Collection, from the original, larger touring exhibition, which was organized by the University of Iowa Museum of Art and the Royal Academy of Arts, London. Fairy painting brought together many opposing elements in the collective psyche and artistic sensibility of its time: rich subject-matter, an escape from the grim elements of an industrial society, an indulgence of new attitudes towards sex, a passion for the unknown, and a denial of the exactitude of photography. Drawing on literary inspiration from Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream to Sir Walter Scott’s Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, as well as the theater, the dance, and music, fairy painters exercised their magic with the precision of the Pre-Raphaelites, aided too by experiments with drugs and spiritualism. -

Lowell Libson Limited

LOWELL LI BSON LTD 2 0 1 0 LOWELL LIBSON LIMITED BRITISH PAINTINGS WATERCOLOURS AND DRAWINGS 3 Clifford Street · Londonw1s 2lf +44 (0)20 7734 8686 · [email protected] www.lowell-libson.com LOWELL LI BSON LTD 2 0 1 0 Our 2010 catalogue includes a diverse group of works ranging from the fascinating and extremely rare drawings of mid seventeenth century London by the Dutch draughtsman Michel 3 Clifford Street · Londonw1s 2lf van Overbeek to the small and exquisitely executed painting of a young geisha by Menpes, an Australian, contained in the artist’s own version of a seventeenth century Dutch frame. Telephone: +44 (0)20 7734 8686 · Email: [email protected] Sandwiched between these two extremes of date and background, the filling comprises Website: www.lowell-libson.com · Fax: +44 (0)20 7734 9997 some quintessentially British works which serve to underline the often forgotten international- The gallery is open by appointment, Monday to Friday ism of ‘British’ art and patronage. Bellucci, born in the Veneto, studied in Dalmatia, and worked The entrance is in Old Burlington Street in Vienna and Düsseldorf before being tempted to England by the Duke of Chandos. Likewise, Boitard, French born and Parisian trained, settled in London where his fluency in the Rococo idiom as a designer and engraver extended to ceramics and enamels. Artists such as Boitard, in the closely knit artistic community of London, provided the grounding of Gainsborough’s early In 2010 Lowell Libson Ltd is exhibiting at: training through which he synthesised -

Forty-Four Turkish Fairy Tales

4 f^ 1'^'1 .1 ^"=1 .y ! : *3P *^ - -J '.; < •J l M ftl %^N:^»^yk:r>>>•.f.v>Jft^ft,v^v^JA:.si,«>>vv.->:.wv>^^ ^ X . / Bffi=.^«f„f--U3«„.3 ^ 3 3333 08iV9yi4^ • REFERENCE iovh^fQ4XC ^""""h^j) 1&^^ h' I ^ rguv ^av^ljl) %lx^ lie? ch t-Ll^^SCve^cconc bo gao»jt>.g;;Jfjw;yj^^fc»^'fel'.:t^r>_Joji, HE MEV/ YOr,. -'"'* AST;'' '.-'I'-'' Page PREFACE ix THE CREATION 1 THE BROTHER AND SISTER 3 FEAR 12 THE THREE ORANGE PERIS 19 THE ROSEBEAUTy 31 39 THE SILENT PRINCESS ,^.^ ;., KARA MUSTAFA THE HERO 50 ' 58 . .V'.';'' •.>: THE WIZARDDERVISH 'r , **^*"' '"' THE FISH-PERI * 64 THE HORSEDEW AND THE WITCH 70 ; CONTENTS Page THE SIMPLETON 11 THE MAGIC TURBAN, THE MAGIC WHIP, AND THE MAGIC CARPET 87 MAHOMET, THE BALD-HEAD 95 THE STORM FIEND 102 THE LAU(}HING APPLE AND THE WEEPING APPLE 117 THE CROWPERI 126 THE FORTY PRINCES AND THE SEVEN-HEADED DRAGON 133 KAMERTAJ, THE MOONHORSE 141 THE BIRD OF SORROW 150 THE ENCHANTED POMEGRANATE BRANCH THE BEAUTY 159 AND . THE MAGIC HAIR-PINS 174 PATIENCE-STONE AND PATIENCE-KNIFE 182 THE DRAGON-PRINCE AND THE STEPMOTHER 188 THE MAGIC MIRROR 198 THE IMP OF THE WELL ' / 206 • -• THE SOOTHSAYER : 213 THE DAUGHTER OF" Th^E' PADISHAH OF KAN- DAHAR 217 SHAH MERAM AND SULTAN SADE 228 vi CONTENTS Page THE WIZARD AND HIS PUPIL 238 THE PADISHAH OF THE THIRTY PERIS 243 THE DECEIVER AND THE THIEF 250 THE SNAKEPERI AND THE MAGIC MIRROR 257 LITTLE HYACINTH'S KIOSK 266 PRINCE AHMED 274 THE LIVER 286 THE FORTUNE TELLER 290 SISTER AND BROTHER 298 SHAH JUSSUF 307 THE BLACK DRAGON AND THE RED DRAGON 316 "MADJUN" 327 THE FORLORN PRINCESS 334 THE BEAUTIFUL HELWA MAIDEN 342 ASTROLOGY 351 KUNTERBUNT 358 MEANING OF TURKISH WORDS 361 Vll V^j^owCQ^: THE stories comprising this collection have been culled with my own hands in the many-hued garden of Turkish folk-lore. -

Christianization of Fairies in Armenia

Armenological Studies Armenian Folia Anglistika Christianization of Fairies in Armenia bout 1700 years ago Armenians were converted into AChristianity. The new religion was brought into Armenia from Assyria and Asia Minor, preached by Gregory the Illuminator, the future bishop of the country, and was adopted as a state religion by Tiridates III, the haughty King of Armenia. Tiridates hoped Christianity would make him independent from his two powerful and dangerous neighbors: Rome and Persia. Though an ally of Armenia, Rome was imposing his patronage on the country, trying to weaken it by making the coronation of Armenian kings the privilege of Alvard Jivanyan Rome. To an extent the Conversion would solve the problem, for Christian kings could not be chosen by Pagan Rome. The Sassanian threat was no less real. A considerable part of Armenian nobility was Zoroastrian and would serve the Sassanians rather than an Armenian King appointed by the Romans. Conversion into Christianity, suggesting intolerance towards Zoroastrianism, would bring Armenian gentry together and distance them from Persia. With the establishment of Christianity in Armenia the Early Church began to show intolerance towards any expression of paganism. Pavstos Buzand’s History of Armenians, though rich in ridicule and criticism, gives a true and valuable picture of the newly converted nation still strongly attached to the pagan religion: They were like children absorbed in their play and their minds were busy with vain and useless things …They wasted their time on unworthy knowledge, pagan traditions and wild barbarous thoughts. They loved their myths and songs and they worshipped their old gods at night as if committing fornication (Buzand, 1987: 70). -

Robert Graves the White Goddess

ROBERT GRAVES THE WHITE GODDESS IN DEDICATION All saints revile her, and all sober men Ruled by the God Apollo's golden mean— In scorn of which I sailed to find her In distant regions likeliest to hold her Whom I desired above all things to know, Sister of the mirage and echo. It was a virtue not to stay, To go my headstrong and heroic way Seeking her out at the volcano's head, Among pack ice, or where the track had faded Beyond the cavern of the seven sleepers: Whose broad high brow was white as any leper's, Whose eyes were blue, with rowan-berry lips, With hair curled honey-coloured to white hips. Green sap of Spring in the young wood a-stir Will celebrate the Mountain Mother, And every song-bird shout awhile for her; But I am gifted, even in November Rawest of seasons, with so huge a sense Of her nakedly worn magnificence I forget cruelty and past betrayal, Careless of where the next bright bolt may fall. FOREWORD am grateful to Philip and Sally Graves, Christopher Hawkes, John Knittel, Valentin Iremonger, Max Mallowan, E. M. Parr, Joshua IPodro, Lynette Roberts, Martin Seymour-Smith, John Heath-Stubbs and numerous correspondents, who have supplied me with source- material for this book: and to Kenneth Gay who has helped me to arrange it. Yet since the first edition appeared in 1946, no expert in ancient Irish or Welsh has offered me the least help in refining my argument, or pointed out any of the errors which are bound to have crept into the text, or even acknowledged my letters. -

George Augustus Sala: the Daily Telegraph's Greatest Special

Gale Primary Sources Start at the source. George Augustus Sala: The Daily Telegraph’s Greatest Special Correspondent Peter Blake University of Brighton Various source media, The Telegraph Historical Archive 1855-2000 EMPOWER™ RESEARCH Early Years locked himself out of his flat and was forced to wander the streets of London all night with nine pence in his The young George Augustus Sala was a precocious pocket. He only found shelter at seven o’clock the literary talent. In 1841, at the age of 13, he wrote his following morning. The resulting article he wrote from first novel entitled Jemmy Jenkins; or the Adventures of a this experience is constructed around his inability to Sweep. The following year he produced his second find a place to sleep, the hardship of life on the streets extended piece of fiction, Gerald Moreland; Or, the of the capital and the subsequent social commentary Forged Will (1842). Although these works were this entailed. While deliberating which journal might unpublished, Sala clearly possessed a considerable accept the article, Sala remembered a connection he literary ability and his vocabulary was enhanced by his and his mother had shared with Charles Dickens. In devouring of the Penny Dreadfuls of the period, along 1837 his mother had been understudy at the St James’s with the ‘Newgate novels’ then in vogue, and Theatre in The Village Coquettes, an operetta written by newspapers like The Times and illustrated newspapers Dickens and composed by John Hullah. Madame Sala and journals like the Illustrated London News and and Dickens went on to become good friends on the Punch. -

CONCEIVING the GODDESS an Old Woman Drawing a Picture of Durga-Mahishasuramardini on a Village Wall, Gujrat State, India

CONCEIVING THE GODDESS An old woman drawing a picture of Durga-Mahishasuramardini on a village wall, Gujrat State, India. Photo courtesy Jyoti Bhatt, Vadodara, India. CONCEIVING THE GODDESS TRANSFORMATION AND APPROPRIATION IN INDIC RELIGIONS Edited by Jayant Bhalchandra Bapat and Ian Mabbett Conceiving the Goddess: Transformation and Appropriation in Indic Religions © Copyright 2017 Copyright of this collection in its entirety belongs to the editors, Jayant Bhalchandra Bapat and Ian Mabbett. Copyright of the individual chapters belongs to the respective authors. All rights reserved. Apart from any uses permitted by Australia’s Copyright Act 1968, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright owners. Inquiries should be directed to the publisher. Monash University Publishing Matheson Library and Information Services Building, 40 Exhibition Walk Monash University Clayton, Victoria 3800, Australia www.publishing.monash.edu Monash University Publishing brings to the world publications which advance the best traditions of humane and enlightened thought. Monash University Publishing titles pass through a rigorous process of independent peer review. www.publishing.monash.edu/books/cg-9781925377309.html Design: Les Thomas. Cover image: The Goddess Sonjai at Wai, Maharashtra State, India. Photograph: Jayant Bhalchandra Bapat. ISBN: 9781925377309 (paperback) ISBN: 9781925377316 (PDF) ISBN: 9781925377606 (ePub) The Monash Asia Series Conceiving the Goddess: Transformation and Appropriation in Indic Religions is published as part of the Monash Asia Series. The Monash Asia Series comprises works that make a significant contribution to our understanding of one or more Asian nations or regions. The individual works that make up this multi-disciplinary series are selected on the basis of their contemporary relevance. -

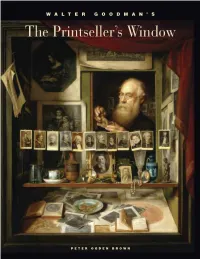

The Printseller's Window: Solving a Painter's Puzzle, on View at the Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester from August 14–November 8, 2009

WALTER GOODMAN’S WALTER GOODMAN’S The Printseller’s Window The Printseller’s Window PETER OGDEN BROWN PETER OGDEN BROWN WALTER GOODMAN’S The Printseller’s Window PETER OGDEN BROWN 500 University Avenue, Rochester NY 14607, mag.rochester.edu Author: Peter O. Brown Editor: John Blanpied Project Coordinator: Marjorie B. Searl Designer: Kathy D’Amanda/MillRace Design Associates Printer: St. Vincent Press First published 2009 in conjunction with the exhibition Walter Goodman’s The Printseller’s Window: Solving a Painter’s Puzzle, on view at the Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester from August 14–November 8, 2009. The exhibition was sponsored by the Thomas and Marion Hawks Memorial Fund, with additional support from Alesco Advisors and an anonymous donor. ISBN 978-0-918098-12-2 (alk. paper) ©2009 Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester. All rights reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation, no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded, or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Every attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions. Cover illustration: Walter Goodman (British, 1838–1912) The Printseller’s Window, 1883 Oil on canvas 52 ¼” x 44 ¾” Marion Stratton Gould Fund, 98.75 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My pursuit of the relatively unknown Victorian painter Walter Goodman and his lost body of work began shortly after the Memorial Art Gallery’s acquisition of The Printseller’s Window1 in 1998. -

'Fairy' in Middle English Romance

'FAIRY' IN MIDDLE ENGLISH ROMANCE Chera A. Cole A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2014 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/6388 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence ‘FAIRY’ IN MIDDLE ENGLISH ROMANCE Chera A. Cole A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the School of English in the University of St Andrews 17 December 2013 i ABSTRACT My thesis, ‘Fairy in Middle English romance’, aims to contribute to the recent resurgence of interest in the literary medieval supernatural by studying the concept of ‘fairy’ as it is presented in fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Middle English romances. This thesis is particularly interested in how the use of ‘fairy’ in Middle English romances serves as an arena in which to play out ‘thought-experiments’ that test anxieties about faith, gender, power, and death. My first chapter considers the concept of fairy in its medieval Christian context by using the romance Melusine as a case study to examine fairies alongside medieval theological explorations of the nature of demons. I then examine the power dynamic of fairy/human relationships and the extent to which having one partner be a fairy affects these explorations of medieval attitudes toward gender relations and hierarchy. The third chapter investigates ‘fairy-like’ women enchantresses in romance and the extent to which fairy is ‘performed’ in romance. -

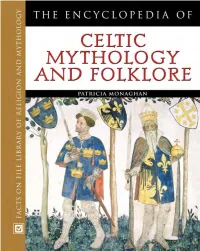

Encyclopedia of CELTIC MYTHOLOGY and FOLKLORE

the encyclopedia of CELTIC MYTHOLOGY AND FOLKLORE Patricia Monaghan The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore Copyright © 2004 by Patricia Monaghan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Monaghan, Patricia. The encyclopedia of Celtic mythology and folklore / Patricia Monaghan. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-4524-0 (alk. paper) 1. Mythology, Celtic—Encyclopedias. 2. Celts—Folklore—Encyclopedias. 3. Legends—Europe—Encyclopedias. I. Title. BL900.M66 2003 299'.16—dc21 2003044944 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Erika K. Arroyo Cover design by Cathy Rincon Printed in the United States of America VB Hermitage 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. CONTENTS 6 INTRODUCTION iv A TO Z ENTRIES 1 BIBLIOGRAPHY 479 INDEX 486 INTRODUCTION 6 Who Were the Celts? tribal names, used by other Europeans as a The terms Celt and Celtic seem familiar today— generic term for the whole people.