Forty-Four Turkish Fairy Tales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

166-90-06 Tel: +38(063)804-46-48 E-Mail: [email protected] Icq: 550-846-545 Skype: Doowopteenagedreams Viber: +38(063)804-46-48 Web

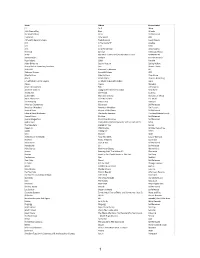

tel: +38(097)725-56-34 tel: +38(099)166-90-06 tel: +38(063)804-46-48 e-mail: [email protected] icq: 550-846-545 skype: doowopteenagedreams viber: +38(063)804-46-48 web: http://jdream.dp.ua CAT ORDER PRICE ITEM CNF ARTIST ALBUM LABEL REL G-055 $15,84 1 CD 883 Uno In Piu CD - Cgd 10/15/2001 G-055 $15,14 1 CD 1910 Fruitgum Company Best Of The 1910 Fruitgum Co CD - 03/01/2008 G-055 $38,41 1 CD 4 Knights Jivin' & Smoothin' CD - Despo Cd 03/15/1998 G-055 $34,75 1 CD 5th Dimension Up Up & Away / Magic Garden / Stoned Soul Picnic CD - N/A G-055 $15,14 1 CD 99 Posse La Vida Que Vendra CD - Ricordi 05/15/2000 G-055 $14,90 1 CD Aa. Vv. I Grandi Successi Dei Cantautori CD - Imports 05/19/2006 G-055 $19,13 1 CD Aa. Vv. Sanremo Festival CD - Imports 07/15/2016 G-055 $15,25 1 CD A'anseltaler Leb'n Anseltaler Party Expres CD - Marlstone Music 06/02/2011 G-055 $18,19 1 CD Abba 2 For 1: Abba/Arrival CD - Polydor 07/07/2009 G-055 $23,23 1 CD Abba Compilation CD - Capitol (emi Austria) 04/27/2009 G-055 $20,65 1 CD Abraham Mateo Abraham Mateo CD - Dro 09/26/2013 G-055 $20,65 1 CD Accordeon 2006 Disque D''or Vol.2 CD - Wagra N/A G-055 $20,65 1 CD Accordeons De France / Various Accordeons De France / Various CD - 06/15/1999 G-055 $26,82 1 CD Ace Of Base The Golden Ratio CD - We Love Music 09/24/2010 G-055 $21,94 1 CD Ace Of Cups It's For You, But Buy It CD - Ace 01/13/2004 G-055 $22,52 1 CD Achim Schultz Think Big CD - 03/03/2008 G-055 $15,25 1 CD Acker Bilk Bridge Over Troubled Waters CD - Spectrum N/A G-055 $29,70 1 EP Ad Libs 7-you'll Always. -

Global City Review International

Global City Review International i s s u i: n u m w i- H i o u k r i: i: n 2 0 0 2 lOlINDINC, !■ DITOR Limey Abrams issiii rniTORS Patricia Dunn and Nina Herzog poiiTRv c o ns m .t a n t : Susan lands CO NTRI B U 11 N G 1- D I TO H S Edith Chevat, Patricia Dunn. Nina Herzog, a n d Susan Lewis MANAGING ANI) I'DITORIAI. HOARD Lisa Bareli t, Eden Coughlin. Patricia Dunn, Joanna Fitzpatrick, Beth Herstein, Nina Herzog, Lance Hunt, Julie Morrisett, Sue Park, a n d Justin Young K FADING SFKIFS PRODUCTION Edith Chevat Ananda La Vita Global City Review is a literary metropolis of the imagination. Edited and produced by writers, it celebrates the difficulties and possibilities of the social world of cit ies, and ot her const ruct ions of community.. .while honoring the inventiveness and originality of ordinary lives. Each pocket-size issue includes stories, poems, memoirs, interviews and essays organized around a broad theme. GLOBAL CITY REVIEW International 2002 NUMBER FOURTEEN COPYRIGHT © 2002 BY GLOBAL CITY PRESS ALL RIGHTS REVERT TO AUTHORS UPON PUBLICATION. Global City Review is published twice yearly. ALL CORRESPONDENCE SHOULD BE SENT TO: GLOBAL CITY REVIEW SIMON H. RIFKIND CENTER FOR THE HUMANITIES THE CITY COLLEGE OF NEW YORK 138TH AND CONVENT AVENUE NEW YORK, NY IOO31 [email protected] GLOBAL CITY REVIEW IS DISTRIBUTED BY BERNHARD DEBOER, INC. ISBN: 1-55605-344-4 GLOBAL CITY REVIEW IS PUBLISHED WITH THE GENEROUS SUPPORT OF THE ROY AND NIUTA TITUS FOUNDATION AND OF THE SIMON H. -

2015 Year in Review

Ar#st Album Record Label !!! As If Warp 11th Dream Day Beet Atlan5c The 4onthefloor All In Self-Released 7 Seconds New Wind BYO A Place To Bury StranGers Transfixia5on Dead Oceans A.F.I. A Fire Inside EP Adeline A.F.I. A.F.I. Nitro A.F.I. Sing The Sorrow Dreamworks The Acid Liminal Infec5ous Music ACTN My Flesh is Weakness/So God Damn Cold Self-Released Tarmac Adam In Place Onesize Records Ryan Adams 1989 Pax AM Adler & Hearne Second Nature SprinG Hollow Aesop Rock & Homeboy Sandman Lice Stones Throw AL 35510 Presence In Absence BC Alabama Shakes Sound & Colour ATO Alberta Cross Alberta Cross Dine Alone Alex G Beach Music Domino Recording Jim Alfredson's Dirty FinGers A Tribute to Big John Pa^on Big O Algiers Algiers Matador Alison Wonderland Run Astralwerks All Them Witches DyinG Surfer Meets His Maker New West All We Are Self Titled Domino Jackie Allen My Favorite Color Hans Strum Music AM & Shawn Lee Celes5al Electric ESL Music The AmazinG Picture You Par5san American Scarecrows Yesteryear Self Released American Wrestlers American Wrestlers Fat Possum Ancient River Keeper of the Dawn Self-Released Edward David Anderson The Loxley Sessions The Roayl Potato Family Animal Hours Do Over Self-Released Animal Magne5sm Black River Rainbow Self Released Aphex Twin Computer Controlled Acous5c Instruments Part 2 Warp The Aquadolls Stoked On You BurGer Aqueduct Wild KniGhts Wichita RecordinGs Aquilo CallinG Me B3SCI Arca Mutant Mute Architecture In Helsinki Now And 4EVA Casual Workout The Arcs Yours, Dreamily Nonesuch Arise Roots Love & War Self-Released Astrobeard S/T Self-Relesed Atlas Genius Inanimate Objects Warner Bros. -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

Lowell Libson Limited

LOWELL LI BSON LTD 2 0 1 0 LOWELL LIBSON LIMITED BRITISH PAINTINGS WATERCOLOURS AND DRAWINGS 3 Clifford Street · Londonw1s 2lf +44 (0)20 7734 8686 · [email protected] www.lowell-libson.com LOWELL LI BSON LTD 2 0 1 0 Our 2010 catalogue includes a diverse group of works ranging from the fascinating and extremely rare drawings of mid seventeenth century London by the Dutch draughtsman Michel 3 Clifford Street · Londonw1s 2lf van Overbeek to the small and exquisitely executed painting of a young geisha by Menpes, an Australian, contained in the artist’s own version of a seventeenth century Dutch frame. Telephone: +44 (0)20 7734 8686 · Email: [email protected] Sandwiched between these two extremes of date and background, the filling comprises Website: www.lowell-libson.com · Fax: +44 (0)20 7734 9997 some quintessentially British works which serve to underline the often forgotten international- The gallery is open by appointment, Monday to Friday ism of ‘British’ art and patronage. Bellucci, born in the Veneto, studied in Dalmatia, and worked The entrance is in Old Burlington Street in Vienna and Düsseldorf before being tempted to England by the Duke of Chandos. Likewise, Boitard, French born and Parisian trained, settled in London where his fluency in the Rococo idiom as a designer and engraver extended to ceramics and enamels. Artists such as Boitard, in the closely knit artistic community of London, provided the grounding of Gainsborough’s early In 2010 Lowell Libson Ltd is exhibiting at: training through which he synthesised -

“All Politicians Are Crooks and Liars”

Blur EXCLUSIVE Alex James on Cameron, Damon & the next album 2 MAY 2015 2 MAY Is protest music dead? Noel Gallagher Enter Shikari Savages “All politicians are Matt Bellamy crooks and liars” The Horrors HAVE THEIR SAY The GEORGE W BUSH W GEORGE Prodigy + Speedy Ortiz STILL STARTING FIRES A$AP Rocky Django Django “They misunderestimated me” David Byrne THE PAST, PRESENT & FUTURE OF MUSIC Palma Violets 2 MAY 2015 | £2.50 US$8.50 | ES€3.90 | CN$6.99 # "% # %$ % & "" " "$ % %"&# " # " %% " "& ### " "& "$# " " % & " " &# ! " % & "% % BAND LIST NEW MUSICAL EXPRESS | 2 MAY 2015 Anna B Savage 23 Matthew E White 51 A$AP Rocky 10 Mogwai 35 Best Coast 43 Muse 33 REGULARS The Big Moon 22 Naked 23 FEATURES Black Rebel Motorcycle Nicky Blitz 24 Club 17 Noel Gallagher 33 4 Blanck Mass 44 Oasis 13 SOUNDING OFF Blur 36 Paddy Hanna 25 6 26 Breeze 25 Palma Violets 34, 42 ON REPEAT The Prodigy Brian Wilson 43 Patrick Watson 43 Braintree’s baddest give us both The Britanys 24 Passion Pit 43 16 IN THE STUDIO Broadbay 23 Pink Teens 24 Radkey barrels on politics, heritage acts and Caribou 33 The Prodigy 26 the terrible state of modern dance Carl Barât & The Jackals 48 Radkey 16 17 ANATOMY music. Oh, and eco light bulbs… Chastity Belt 45 Refused 6, 13 Coneheads 23 Remi Kabaka 15 David Byrne 12 Ride 21 OF AN ALBUM De La Soul 7 Rihanna 6 Black Rebel Motorcycle Club 32 Protest music Django Django 15, 44 Rolo Tomassi 6 – ‘BRMC’ Drenge 33 Rozi Plain 24 On the eve of the general election, we Du Blonde 35 Run The Jewels 6 -

Christianization of Fairies in Armenia

Armenological Studies Armenian Folia Anglistika Christianization of Fairies in Armenia bout 1700 years ago Armenians were converted into AChristianity. The new religion was brought into Armenia from Assyria and Asia Minor, preached by Gregory the Illuminator, the future bishop of the country, and was adopted as a state religion by Tiridates III, the haughty King of Armenia. Tiridates hoped Christianity would make him independent from his two powerful and dangerous neighbors: Rome and Persia. Though an ally of Armenia, Rome was imposing his patronage on the country, trying to weaken it by making the coronation of Armenian kings the privilege of Alvard Jivanyan Rome. To an extent the Conversion would solve the problem, for Christian kings could not be chosen by Pagan Rome. The Sassanian threat was no less real. A considerable part of Armenian nobility was Zoroastrian and would serve the Sassanians rather than an Armenian King appointed by the Romans. Conversion into Christianity, suggesting intolerance towards Zoroastrianism, would bring Armenian gentry together and distance them from Persia. With the establishment of Christianity in Armenia the Early Church began to show intolerance towards any expression of paganism. Pavstos Buzand’s History of Armenians, though rich in ridicule and criticism, gives a true and valuable picture of the newly converted nation still strongly attached to the pagan religion: They were like children absorbed in their play and their minds were busy with vain and useless things …They wasted their time on unworthy knowledge, pagan traditions and wild barbarous thoughts. They loved their myths and songs and they worshipped their old gods at night as if committing fornication (Buzand, 1987: 70). -

BLUR, Il 28 Aprile Esce Finalmente Il Nuovissimo Album Intitolato the Magic Whip

DOMENICA 22 FEBBRAIO 2015 Dopo 16 anni dal loro ultimo lavoro come BLUR, il 28 aprile esce finalmente il nuovissimo album intitolato The Magic Whip. Blur: The Magic Whip il nuovo La registrazione, iniziata durante una pausa di 5 giorni durante il tour album in uscita il 28 aprile primaverile del 2013 - agli Avon Studios di Kowloon, Hong Kong - è stata messa da parte per terminare il tour e poi ognuno è tornato alle Concerto ad Hyde Park - Londra - 20 giugno rispettive vite. 2015 Lo scorso novembre Graham Coxon ha ripreso in mano quelle tracce, ha chiamato il vecchio produttore dei Blur Stephen Street e ha ricominciato a lavorare su quel materiale con tutta la band. Albarn ha poi aggiunto i LA REDAZIONE testi e il risultato sono le 12 canzoni che compongono THE MAGIC WHIP: Lonesome Street, New World Towers, Go Out, Ice Cream Man, Thought I Was a Spaceman, I Broadcast, My Terracotta Heart, There are Too Many of Us, Ghost Ship, Pyongyang, Ong Ong, Mirror Ball. [email protected] Il prossimo 20 giugno i BLUR terranno un concerto nello storico parco SPETTACOLINEWS.IT londinese di Hyde Park - unica band ad averci suonato per ben 4 volte - all'interno del British Summer Time Hyde Park. La notizia del nuovo album dei BLUR è stata data in esclusiva su facebook durante una conferenza stampa in diretta streaming dal quartiere Chinatown di Londra, a cui i fan potevano partecipare inviando le proprie domande: un occasione speciale che i BLUR hanno voluto dare ai milioni di fan parlando loro direttamente in tempo reale e rispondendo alle domande sulla pagina del loro profilo. -

Robert Graves the White Goddess

ROBERT GRAVES THE WHITE GODDESS IN DEDICATION All saints revile her, and all sober men Ruled by the God Apollo's golden mean— In scorn of which I sailed to find her In distant regions likeliest to hold her Whom I desired above all things to know, Sister of the mirage and echo. It was a virtue not to stay, To go my headstrong and heroic way Seeking her out at the volcano's head, Among pack ice, or where the track had faded Beyond the cavern of the seven sleepers: Whose broad high brow was white as any leper's, Whose eyes were blue, with rowan-berry lips, With hair curled honey-coloured to white hips. Green sap of Spring in the young wood a-stir Will celebrate the Mountain Mother, And every song-bird shout awhile for her; But I am gifted, even in November Rawest of seasons, with so huge a sense Of her nakedly worn magnificence I forget cruelty and past betrayal, Careless of where the next bright bolt may fall. FOREWORD am grateful to Philip and Sally Graves, Christopher Hawkes, John Knittel, Valentin Iremonger, Max Mallowan, E. M. Parr, Joshua IPodro, Lynette Roberts, Martin Seymour-Smith, John Heath-Stubbs and numerous correspondents, who have supplied me with source- material for this book: and to Kenneth Gay who has helped me to arrange it. Yet since the first edition appeared in 1946, no expert in ancient Irish or Welsh has offered me the least help in refining my argument, or pointed out any of the errors which are bound to have crept into the text, or even acknowledged my letters. -

Book \\ Damon Albarn: Blur, Gorillaz and Other Fables (Paperback) / Read

HIOMW7CEH5 < Damon Albarn: Blur, Gorillaz and Other Fables (Paperback) / Kindle Damon A lbarn: Blur, Gorillaz and Oth er Fables (Paperback) By David Nolan, Martin Roach John Blake Publishing Ltd, United Kingdom, 2016. Paperback. Condition: New. Revised, Updated. Language: English . Brand New Book. Damon Albarn was the frontman of Blur and the face of Britpop. While his peers have gradually fallen by the wayside, Albarn has survived Britpop to completely re-invent himself as the mastermind behind the global phenomenon that is Gorillaz. With his eclectic solo projects - such as the currently much-revered The Good, The Bad and the Queen - and his work with legends like Soul music icon Bobby Womack, he has proven again and again that he is one of British music s most respected, innovative and important personalities. And in 2015, with the release of The Magic Whip, Blur s first album for over a decade, Damon Albarn will take his place once more as an iconic jewel in the crown of the British music scene. This fully up-to- date book - the only available dedicated biography of Albarn - covers his multiple musical personas in depth, with first-hand interviews by those close to Albarn in his formative years, as well as social and musical context that covers the Britpop era and Albarn s re-emergence as the Godfather to the i-Pod generation. READ ONLINE [ 1.78 MB ] Reviews Very helpful to all of class of folks. This is certainly for all who statte there had not been a worthy of studying. Once you begin to read the book, it is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding. -

CONCEIVING the GODDESS an Old Woman Drawing a Picture of Durga-Mahishasuramardini on a Village Wall, Gujrat State, India

CONCEIVING THE GODDESS An old woman drawing a picture of Durga-Mahishasuramardini on a village wall, Gujrat State, India. Photo courtesy Jyoti Bhatt, Vadodara, India. CONCEIVING THE GODDESS TRANSFORMATION AND APPROPRIATION IN INDIC RELIGIONS Edited by Jayant Bhalchandra Bapat and Ian Mabbett Conceiving the Goddess: Transformation and Appropriation in Indic Religions © Copyright 2017 Copyright of this collection in its entirety belongs to the editors, Jayant Bhalchandra Bapat and Ian Mabbett. Copyright of the individual chapters belongs to the respective authors. All rights reserved. Apart from any uses permitted by Australia’s Copyright Act 1968, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright owners. Inquiries should be directed to the publisher. Monash University Publishing Matheson Library and Information Services Building, 40 Exhibition Walk Monash University Clayton, Victoria 3800, Australia www.publishing.monash.edu Monash University Publishing brings to the world publications which advance the best traditions of humane and enlightened thought. Monash University Publishing titles pass through a rigorous process of independent peer review. www.publishing.monash.edu/books/cg-9781925377309.html Design: Les Thomas. Cover image: The Goddess Sonjai at Wai, Maharashtra State, India. Photograph: Jayant Bhalchandra Bapat. ISBN: 9781925377309 (paperback) ISBN: 9781925377316 (PDF) ISBN: 9781925377606 (ePub) The Monash Asia Series Conceiving the Goddess: Transformation and Appropriation in Indic Religions is published as part of the Monash Asia Series. The Monash Asia Series comprises works that make a significant contribution to our understanding of one or more Asian nations or regions. The individual works that make up this multi-disciplinary series are selected on the basis of their contemporary relevance. -

My Autobiography and Reminiscences

s^ FURTHER REMINISCENCES \V. p. FRITH. Painted by Douglas Cowper in 1838. MY AUTOBIOGRAPHY AND REMINISCENCES BY W. p. FKITH, E.A. CHEVALIER OP THE LEGION OP HONOR AND OP THE ORDER OP LEOPOLD ; MEMBER OP THE ROYAL ACADEMY OP BELGIUM, AND OP THE ACADEMIES OP STOCKHOLM, ^^ENNA, AND ANTWERP " ' The pencil speaks the tongue of every land Dryden Vol. II. NEW YORK HARPER & BROTHERS, FRANKLIN SQUARE 1888 Art Libraxj f 3IAg. TO MY SISTER WITHOUT WHOSE LOVING CARE OF MY EARLY LETTERS THIS VOLUME WOULD HAVE SUFFERED 3 {Dcbicfltc THESE FURTHER RE^IINISCENCES WITH TRUE AFFECTION CONTENTS. CHAPTER PAGE INTRODUCTION 1 I. GREAT NAMES, AND THE VALUE OF THEM ... 9 II. PRELUDE TO CORRESPONDENCE 21 III. EARLY CORRESPONDENCE 25 IV. ASYLUM EXPERIENCES 58 V. ANECDOTES VARIOUS 71 VI. AN OVER-TRUE TALE 102 VII. SCRAPS 114 VIII. A YORKSHIRE BLUNDER, AND SCRAPS CONTINUED. 122 IX. RICHARD DADD 131 X. AN OLD-FASHIONED PATRON 143 XI. ANOTHER DINNER AT IVY COTTAGE 154 XII. CHARLES DICKENS 165 XIII. SIR EDWIN LANDSEER 171 XIV. GEORGE AUGUSTUS SALA 179 XV. JOHN LEECH 187 XVI. SHIRLEY BROOKS 194 XVII. ADMIRATION 209 XVIII. ON SELF-DELUSION AND OTHER MATTERS . .217 XIX. FASHION IN ART .... - 225 XX. A STORY OF A SNOWY NIGHT 232 XXI. ENGLISH ART AND FRENCH INFLUENCE .... 237 XXII. IGNORANCE OF ART 244 Vlll CONTENTS. CHAPTER PAGE XXIII. ORATORY 253 XXIV. SUPPOSITITIOUS PICTURES 260 XXV. A VARIETY OF LETTERS FROM VARIOUS PEOPLE . 265 XXVI. MRS. MAXWELL 289 XXVII. BOOK ILLUSTRATORS 294 XXVIII. MORE PEOPLE WHOM I HAVE KNOWN .... 301 INDEX 3I5 MY AUTOBIOGEAPHY AND KEMINISCEKCES.