American Papers 2017 ~ 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Fall 2020 Virtual Commencement Program

FALL 2020 VIRTUAL COMMENCEMENT DECEMBER 18 Contents About the SIU System .............................................................................................................................................. 3 About Southern Illinois University Edwardsville ................................................................................................. 4 SIUE’s Mission, Vision, Values and Statement on Diversity .............................................................................. 5 Academics at SIUE ................................................................................................................................................... 6 History of Academic Regalia ................................................................................................................................. 8 Commencement at SIUE ......................................................................................................................................... 9 Academic and Other Recognitions .................................................................................................................... 10 Honorary Degree ................................................................................................................................................... 12 Distinguished Service Award ............................................................................................................................... 13 College of Arts and Sciences: Undergraduate Ceremony ............................................................................. -

Annual Report 2017

Koninklijke Sterrenwacht van België Observatoire royal de Belgique Royal Observatory of Belgium Jaarverslag 2017 Rapport Annuel 2017 Annual Report 2017 Cover illustration: Above: One billion star map of our galaxy created with the optical telescope of the satellite Gaia (Credit: ESA/Gaia/DPAC). Below: Three armillary spheres designed by Jérôme de Lalande in 1775. Left: the spherical sphere; in the centre: the geocentric model of our solar system (with the Earth in the centre); right: the heliocentric model of our solar system (with the Sun in the centre). Royal Observatory of Belgium - Annual Report 2017 2 De activiteiten beschreven in dit verslag werden ondersteund door Les activités décrites dans ce rapport ont été soutenues par The activities described in this report were supported by De POD Wetenschapsbeleid De Nationale Loterij Le SPP Politique Scientifique La Loterie Nationale The Belgian Science Policy The National Lottery Het Europees Ruimtevaartagentschap De Europese Gemeenschap L’Agence Spatiale Européenne La Communauté Européenne The European Space Agency The European Community Het Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek – Le Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique Vlaanderen Royal Observatory of Belgium - Annual Report 2017 3 Table of contents Preface .................................................................................................................................................... 6 Reference Systems and Planetology ...................................................................................................... -

The YA Novel in the Digital Age by Amy Bright a Thesis

The YA Novel in the Digital Age by Amy Bright A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies University of Alberta © Amy Bright, 2016 Abstract Recent research by Neilsen reports that adult readers purchase 80% of all young adult novels sold, even though young adult literature is a category ostensibly targeted towards teenage readers (Gilmore). More than ever before, young adult (YA) literature is at the center of some of the most interesting literary conversations, as writers, readers, and publishers discuss its wide appeal in the twenty-first century. My dissertation joins this vibrant discussion by examining the ways in which YA literature has transformed to respond to changing social and technological contexts. Today, writing, reading, and marketing YA means engaging with technological advances, multiliteracies and multimodalities, and cultural and social perspectives. A critical examination of five YA texts – Markus Zusak’s The Book Thief, Libba Bray’s Beauty Queens, Daniel Handler’s Why We Broke Up, John Green’s The Fault in Our Stars, and Jaclyn Moriarty’s The Ghosts of Ashbury High – helps to shape understanding about the changes and the challenges facing this category of literature as it responds in a variety of ways to new contexts. In the first chapter, I explore the history of YA literature in order to trace the ways that this literary category has changed in response to new conditions to appeal to and serve a new generation of readers, readers with different experiences, concerns, and contexts over time. -

Board Certified Fellows

AMERICAN BOARD OF MEDICOLEGAL DEATH INVESTIGATORS Certificant Directory As of September 30, 2021 BOARD CERTIFIED FELLOWS Addison, Krysten Leigh (Inactive) BC2286 Allmon, James L. BC855 Travis County Medical Examiner's Office Sangamon County Coroner's Office 1213 Sabine Street 200 South 9th, Room 203 PO Box 1748 Springfield, IL 62701 Austin, TX 78767 Amini, Navid BC2281 Appleberry, Sherronda BC1721 Olmsted Medical Examiner's Office Adams and Broomfield County Office of the Coroner 200 1st Street Southwest 330 North 19th Avenue Rochester, MN 55905 Brighton, CO 80601 Applegate, MD, David T. BC1829 Archer, Meredith D. BC1036 Union County Coroner's Office Mohave County Medical Examiner 128 South Main Street 1145 Aviation Drive Unit A Marysville, OH 43040 Lake Havasu, AZ 86404 Bailey, Ted E. (Inactive) BC229 Bailey, Sanisha Renee BC1754 Gwinnett County Medical Examiner's Office Virginia Office of the Chief Medical Examiner 320 Hurricane Shoals Road, NE Central District Lawrenceville, GA 30046 400 East Jackson Street Richmond, VA 23219 Balacki, Alexander J BC1513 Banks, Elsie-Kay BC3039 Montgomery County Coroner's Office Maine Office of the Chief Medical Examiner 1430 Dekalb Street 30 Hospital Street PO Box 311 Augusta, ME 04333 Norristown, PA 19404 Bautista, Ian BC2185 Bayer, Lindsey A. BC875 New York City Office of Chief Medical Examiner District 5 and 24 Medical Examiner Office 421 East 26th Street 809 Pine Street New York, NY 10016 Leesburg, FL 34756 Beck, Shari L BC327 Beckham, Phinon Phillips BC2305 Sedgwick Co Reg. Forensic Science Center Virginia Office of the Chief Medical Examiner 1109 N. Minneapolis Northern District Wichita, KS 67214 10850 Pyramid Place, Suite 121 Manassas, VA 20110 Bednar Keefe, Gale M. -

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America There are approximately 101,135sexual abuse claims filed. Of those claims, the Tort Claimants’ Committee estimates that there are approximately 83,807 unique claims if the amended and superseded and multiple claims filed on account of the same survivor are removed. The summary of sexual abuse claims below uses the set of 83,807 of claim for purposes of claims summary below.1 The Tort Claimants’ Committee has broken down the sexual abuse claims in various categories for the purpose of disclosing where and when the sexual abuse claims arose and the identity of certain of the parties that are implicated in the alleged sexual abuse. Attached hereto as Exhibit 1 is a chart that shows the sexual abuse claims broken down by the year in which they first arose. Please note that there approximately 10,500 claims did not provide a date for when the sexual abuse occurred. As a result, those claims have not been assigned a year in which the abuse first arose. Attached hereto as Exhibit 2 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the state or jurisdiction in which they arose. Please note there are approximately 7,186 claims that did not provide a location of abuse. Those claims are reflected by YY or ZZ in the codes used to identify the applicable state or jurisdiction. Those claims have not been assigned a state or other jurisdiction. Attached hereto as Exhibit 3 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the Local Council implicated in the sexual abuse. -

COURT of CLAIMS of THE

REPORTS ,I OF Cases Argued and Determined IN THE COURT of CLAIMS OF THE STATE OF ILLINOIS . VOLUME 44 Containing cases in which opinions were filed and orders of dismissal entered, without opinion for: Fiscal Year 1992 - July 1, 1991- June 30, 1992 SPRINGFIELD, ILLINOIS 1-993 (Printed by authority of the State of Illinois) (X24064-300-7/93) PREFACE The opinions of the Court of Claims reported herein are published by authority of the provisions of Section 18 of the Court of Claims Act, 705 ILCS 505/1 et seq., formerly 111. Rev. Stat. 1991, ch. 37, par. 439.1 et seq. The Court of Claims has exclusive jurisdiction to hear and determine the following matters: (a) all claims against the State of Illinois founded upon any law of the State, or upon any regulation thereunder by an executive or administrative officer or agency, other than claims arising under the Workers’ Compensation Act or the Workers’ Occupational Diseases Act, or claims for certain expenses in civil litigation, (b) all claims against the State founded upon any contract entered into with the State, (c) all claims against the State for time unjustly served in prisons of this State where the persons imprisoned shall receive a pardon from the Governor stating that such pardon is issued on the grounds of innocence of the crime for which they were imprisoned, (d) all claims against the State in cases sounding in tort, (e) all claims for recoupment made by the State against any Claimant, (f) certain claims to compel replacement of a lost or destroyed State warrant, (g) certain claims based on torts by escaped inmates of State institutions, (h) certain representation and indemnification cases, (i) all claims pursuant to the Law Enforcement Officers, Civil Defense Workers, Civil Air Patrol Members, Paramedics, Firemen & State Employees Compensation Act, (j) all claims pursuant to the Illinois National Guardsman’s Compensation Act, and (k) all claims pursuant to the Crime Victims Compen- sation Act. -

Superrotation on Venus, on Titan, and Elsewhere

EA46CH08_Read ARI 25 April 2018 12:36 Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences Superrotation on Venus, on Titan, and Elsewhere Peter L. Read1 and Sebastien Lebonnois2 1Clarendon Laboratory, Department of Physics, University of Oxford, Oxford OX1 3PU, United Kingdom; email: [email protected] 2Laboratoire de Met´ eorologie´ Dynamique (LMD/IPSL), Sorbonne Universites,´ UPMC Univ Paris 06, ENS, PSL Research University, Ecole Polytechnique, Universite´ Paris Saclay, CNRS, 75000 Paris, France Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2018. 46:175–202 Keywords First published as a Review in Advance on atmospheres, dynamics, waves, Hadley circulation, Venus, Titan March 14, 2018 The Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences is Abstract online at earth.annualreviews.org The superrotation of the atmospheres of Venus and Titan has puzzled dy- https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-earth-082517- Access provided by CNRS-Multi-Site on 02/15/19. For personal use only. namicists for many years and seems to put these planets in a very different 010137 dynamical regime from most other planets. In this review, we consider how Copyright c 2018 by Annual Reviews. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2018.46:175-202. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org to define superrotation objectively and explore the constraints that deter- All rights reserved mine its occurrence. Atmospheric superrotation also occurs elsewhere in the Solar System and beyond, and we compare Venus and Titan with Earth and other planets for which wind estimates are available. The extreme super- ANNUAL REVIEWS Further rotation on Venus and Titan poses some difficult challenges for numerical Click here to view this article's online features: models of atmospheric circulation, much more difficult than for more rapidly • Download figures as PPT slides rotating planets such as Earth or Mars. -

By Sarah J Griffith

THE MORAL EGOTIST: EVOLUTION OF STYLE IN KURT VONNEGUT’S SATIRE by Sarah J Griffith The Moral Egotist: Evolution of Style in Kurt Vonnegut’s Satire by Sarah J Griffith A thesis presented for the B.A. Degree with Honors in The Department of English University of Michigan Spring 2008 © 2008 Sarah J Griffith Acknowledgements I would like to thank my teachers, advisors, friends, and family without whose support this project may never have become a reality. My thesis advisor, Eric Rabkin, has been an absolutely invaluable resource of both support and tough-love. He earned my respect on the first day we met and I felt compelled to spend the following weeks drafting a project statement grand enough to satisfy his high standards. He is a phenomenal mentor and academic from whom I have learned more about writing in six months than ever before. During the writing process, my teammates and friends were constant sources of alternate encouragement, guidance, and comic relief. Many thanks to Tyler Kinley for providing a tireless and creative ear for the development of my ideas, though I am fortunate in that this comes as no surprise. Most importantly, much appreciation goes to my overwhelmingly supportive parents who affirmed their love for me one more time in soldiering through the early drafts of my writing. Thanks to my father from whom I get my passion for language and my mother whose unmatched patience and compassion have buoyed me up time and again throughout this intensive project. Gratitude is also due to both of them for my opportunity to attend the University of Michigan to meet and work with all of the incredible individuals mentioned above. -

AMERICAN LITERARY MINIMALISM by ROBERT CHARLES

AMERICAN LITERARY MINIMALISM by ROBERT CHARLES CLARK (Under the Direction of James Nagel) ABSTRACT American Literary Minimalism stands as an important yet misunderstood stylistic movement. It is an extension of aesthetics established by a diverse group of authors active in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that includes Amy Lowell, William Carlos Williams, and Ezra Pound. Works within the tradition reflect several qualities: the prose is “spare” and “clean”; important plot details are often omitted or left out; practitioners tend to excise material during the editing process; and stories tend to be about “common people” as opposed to the powerful and aristocratic. While these descriptors and the many others that have been posited over the years are in some ways helpful, the mode remains poorly defined. The core idea that differentiates American Minimalism from other movements is that prose and poetry should be extremely efficient, allusive, and implicative. The language in this type of fiction tends to be simple and direct. Narrators do not often use ornate adjectives and rarely offer effusive descriptions of scenery or extensive detail about characters’ backgrounds. Because authors tend to use few words, each is invested with a heightened sense of interpretive significance. Allusion and implication by omission are often employed as a means to compensate for limited exposition, to add depth to stories that on the surface may seem superficial or incomplete. Despite being scattered among eleven decades, American Minimalists share a common aesthetic. They were not so much enamored with the idea that “less is more” but that it is possible to write compact prose that still achieves depth of setting, characterization, and plot without including long passages of exposition. -

2017 High School National Tournament Results

June 18-23, 2017 These unofficial un-audited electronic results have been provided as a service of the National Speech and Debate Association. Bruno E. Jacob / Pi Kappa Delta National Award in Speech National Speech & Debate Tournament 1 1773 Gabrielino HS, California Coached by Derek Yuill 2 1718 Bellarmine College Prep, California 3 1700 Apple Valley HS, Minnesota 4 1683 Plano Sr HS, Texas 1683 Moorhead HS, Minnesota 6 1643 West HS – Iowa City, Iowa 7 1632 Regis HS, New York 8 1622 Eagan HS, Minnesota 9 1580 Albuquerque Academy, New Mexico 10 1579 Glenbrook North HS, Illinois These unofficial un-audited electronic results have been provided as a service of the National Speech and Debate Association. Karl E. Mundt Sweepstakes Award John C. Stennis Congressional Debate 1 213 Ridge HS, New Jersey Coach David Yastremski 2 200 Riverside HS, South Carolina 3 198 Bellarmine College Prep, California 4 187 Syosset HS, New York 187 Bellaire HS, Texas 6 181 Plano Sr HS, Texas 7 175 Gilmour Academy, Ohio 8 171 Asheville HS, North Carolina 9 167 Wichita East HS, Kansas 167 Carroll HS – Southlake, Texas These unofficial un-audited electronic results have been provided as a service of the National Speech and Debate Association. 2017 National Speech & Debate Association Lanny D. and B. J. Naegelin Dramatic Interp presented by Simpson College Code Name School State Round 7 Round 8 Round 9 Round 10 Round 11 Round 12 7-12 11-12 Place A304 Christian Wikoff Grand Prairie Fine Arts Academy TX 5 1 2 3 2 2 3 2 6 3 4 4 3 2 7 7 7 7 7 3 6 7 93 56 14th A164 ABigail -

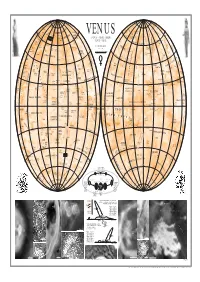

1 : 45 000 000 E a CORONA D T N O M E Or E ASPASIA T Sa MM= KM S R

N N 80° 80° 80° Dennitsa D. 80° Y LO S Sz um U N éla yn H EG nya -U I BACHUE URO IA D d P ANAHIT CHKA PLANIT ors Klenova yr L CORONA M POMONA a D A ET CORONA o N Renpet IS r I R CORONA T sa T Mons EG FERONIA ET L I I H A . Thallo O A U u Tünde CORONA F S k L Mons 60° re R 60° 60° R a 60° . y j R E e u M Ivka a VACUNA GI l m O k . es E Allat Do O EARHART o i p e Margit N OTAU nt M T rsa CORONA a t a D E o I R Melia CORONA n o r o s M M .Wanda S H TA D a L O CORONA a n g I S Akn Mons o B . t Y a x r Mokosha N Rita e w U E M e A AUDRA D s R V s E S R l S VENUS FAKAHOTU a Mons L E E A l ES o GI K A T NIGHTINGALE I S N P O HM Cleopatra M RTUN A VÉNUSZ VENERA CORONA r V I L P FO PLANITIA ÂÅÍÅÐÀ s A o CORONA M e LA N P N n K a IT MOIRA s UM . a Hemera Dorsa A Iris DorsaBarsova 11 km a E IA TESSERA t t m A e a VENUŠE WENUS Hiei Chu n R a r A R E s T S DEMETER i A d ES D L A o Patera A r IS T N o R s r TA VIRIL CORONA s P s u e a L A N I T I A P p nt A o A L t e o N s BEIWE s M A ir u K A D G U Dan Baba-Jaga 1 : 45 000 000 E a CORONA D T N o M e or E ASPASIA t sa MM= KM S r . -

Sanibel-Captiva Conservation Foundation

SANIBEL-CAPTIVA CONSERVATION FOUNDATION SCCF ANNUAL REPORT • FISCAL YEAR 2018-2019 Founded in 1967, SCCF is dedicated to the conservation of coastal habitats and aquatic resources on Sanibel and Captiva and in the surrounding watershed through its program areas: Marine Laboratory Wildlife & Habitat Management Natural Resource Policy Native Landscapes & Garden Center Sea Turtles & Shorebirds Environmental Education Land Acquisition & Stewardship Connections November 2019 Dear Valued Members and Friends, What a year this has been! In September 2018 we announced SCCF’s new CEO and we spent the fall celebrating Erick Lindblad’s extraordinary 33-year tenure as a mentor and leader. Ryan took the helm in January 2019, and the ensuing months have featured a very successful transition and the emergence of new ideas and energy – including an update to SCCF’s strategic plan. We are entering the future bravely and thoughtfully and want to share several themes that will Doug Ryckman and Ryan Orgera guide SCCF in that future. COMMITMENT - Erick and the extraordinary SCCF staff shaped a culture of love for their jobs and appreciation of each other. Our dedicated team members are committed to SCCF’s mission and pour their hearts into all of its work. We are extremely proud of our people and the values they continue to demonstrate every day. VIGILANCE - SCCF has fought to protect our islands for over 52 years. We have been highly successful, preserving over 1,850 acres, educating innumerable citizens and visitors, and advocating for nature in Fort Myers, Tallahassee, and Washington. The SCCF RECON Network is our islands’ first line of defense in monitoring coastal water quality, and our sea turtle and shorebird programs nurture fragile wildlife populations.