A More Comprehensive Habitable Zone for Finding Life on Other Planets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building Blocks That Fall from the Sky

Building blocks that fall from the sky How did life on Earth begin? Scientists from the “Heidelberg Initiative for the Origin of Life” have set about answering this truly existential question. Indeed, they are going one step further and examining the conditions under which life can emerge. The initiative was founded by Thomas Henning, Director at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, and brings together researchers from chemistry, physics and the geological and biological sciences. 18 MaxPlanckResearch 3 | 18 FOCUS_The Origin of Life TEXT THOMAS BUEHRKE he great questions of our exis- However, recent developments are The initiative was triggered by the dis- tence are the ones that fasci- forcing researchers to break down this covery of an ever greater number of nate us the most: how did the specialization and combine different rocky planets orbiting around stars oth- universe evolve, and how did disciplines. “That’s what we’re trying er than the Sun. “We now know that Earth form and life begin? to do with the Heidelberg Initiative terrestrial planets of this kind are more DoesT life exist anywhere else, or are we for the Origins of Life, which was commonplace than the Jupiter-like gas alone in the vastness of space? By ap- founded three years ago,” says Thom- giants we identified initially,” says Hen- proaching these puzzles from various as Henning. HIFOL, as the initiative’s ning. Accordingly, our Milky Way alone angles, scientists can answer different as- name is abbreviated, not only incor- is home to billions of rocky planets, pects of this question. -

Exploring Exoplanet Populations with NASA's Kepler Mission

SPECIAL FEATURE: PERSPECTIVE PERSPECTIVE SPECIAL FEATURE: Exploring exoplanet populations with NASA’s Kepler Mission Natalie M. Batalha1 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, 94035 CA Edited by Adam S. Burrows, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, and accepted by the Editorial Board June 3, 2014 (received for review January 15, 2014) The Kepler Mission is exploring the diversity of planets and planetary systems. Its legacy will be a catalog of discoveries sufficient for computing planet occurrence rates as a function of size, orbital period, star type, and insolation flux.The mission has made significant progress toward achieving that goal. Over 3,500 transiting exoplanets have been identified from the analysis of the first 3 y of data, 100 planets of which are in the habitable zone. The catalog has a high reliability rate (85–90% averaged over the period/radius plane), which is improving as follow-up observations continue. Dynamical (e.g., velocimetry and transit timing) and statistical methods have confirmed and characterized hundreds of planets over a large range of sizes and compositions for both single- and multiple-star systems. Population studies suggest that planets abound in our galaxy and that small planets are particularly frequent. Here, I report on the progress Kepler has made measuring the prevalence of exoplanets orbiting within one astronomical unit of their host stars in support of the National Aeronautics and Space Admin- istration’s long-term goal of finding habitable environments beyond the solar system. planet detection | transit photometry Searching for evidence of life beyond Earth is the Sun would produce an 84-ppm signal Translating Kepler’s discovery catalog into one of the primary goals of science agencies lasting ∼13 h. -

Formation of TRAPPIST-1

EPSC Abstracts Vol. 11, EPSC2017-265, 2017 European Planetary Science Congress 2017 EEuropeaPn PlanetarSy Science CCongress c Author(s) 2017 Formation of TRAPPIST-1 C.W Ormel, B. Liu and D. Schoonenberg University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands ([email protected]) Abstract start to drift by aerodynamical drag. However, this growth+drift occurs in an inside-out fashion, which We present a model for the formation of the recently- does not result in strong particle pileups needed to discovered TRAPPIST-1 planetary system. In our sce- trigger planetesimal formation by, e.g., the streaming nario planets form in the interior regions, by accre- instability [3]. (a) We propose that the H2O iceline (r 0.1 au for TRAPPIST-1) is the place where tion of mm to cm-size particles (pebbles) that drifted ice ≈ the local solids-to-gas ratio can reach 1, either by from the outer disk. This scenario has several ad- ∼ vantages: it connects to the observation that disks are condensation of the vapor [9] or by pileup of ice-free made up of pebbles, it is efficient, it explains why the (silicate) grains [2, 8]. Under these conditions plan- TRAPPIST-1 planets are Earth mass, and it provides etary embryos can form. (b) Due to type I migration, ∼ a rationale for the system’s architecture. embryos cross the iceline and enter the ice-free region. (c) There, silicate pebbles are smaller because of col- lisional fragmentation. Nevertheless, pebble accretion 1. Introduction remains efficient and growth is fast [6]. (d) At approx- TRAPPIST-1 is an M8 main-sequence star located at a imately Earth masses embryos reach their pebble iso- distance of 12 pc. -

Lecture-29 (PDF)

Life in the Universe Orin Harris and Greg Anderson Department of Physics & Astronomy Northeastern Illinois University Spring 2021 c 2012-2021 G. Anderson., O. Harris Universe: Past, Present & Future – slide 1 / 95 Overview Dating Rocks Life on Earth How Did Life Arise? Life in the Solar System Life Around Other Stars Interstellar Travel SETI Review c 2012-2021 G. Anderson., O. Harris Universe: Past, Present & Future – slide 2 / 95 Dating Rocks Zircon Dating Sedimentary Grand Canyon Life on Earth How Did Life Arise? Life in the Solar System Life Around Dating Rocks Other Stars Interstellar Travel SETI Review c 2012-2021 G. Anderson., O. Harris Universe: Past, Present & Future – slide 3 / 95 Zircon Dating Zircon, (ZrSiO4), minerals incorporate trace amounts of uranium but reject lead. Naturally occuring uranium: • U-238: 99.27% • U-235: 0.72% Decay chains: • 238U −→ 206Pb, τ =4.47 Gyrs. • 235U −→ 207Pb, τ = 704 Myrs. 1956, Clair Camron Patterson dated the Canyon Diablo meteorite: τ =4.55 Gyrs. c 2012-2021 G. Anderson., O. Harris Universe: Past, Present & Future – slide 4 / 95 Dating Sedimentary Rocks • Relative ages: Deeper layers were deposited earlier • Absolute ages: Decay of radioactive isotopes old (deposited last) oldest (depositedolder first) c 2012-2021 G. Anderson., O. Harris Universe: Past, Present & Future – slide 5 / 95 Grand Canyon: Earth History from 200 million - 2 billion yrs ago. Dating Rocks Life on Earth Earth History Timeline Late Heavy Bombardment Hadean Shark Bay Stromatolites Cyanobacteria Q: Earliest Fossils? Life on Earth O2 History Q: Life on Earth How Did Life Arise? Life in the Solar System Life Around Other Stars Interstellar Travel SETI Review c 2012-2021 G. -

EPSC2012-280 2012 European Planetary Science Congress 2012 Eeuropeapn Planetarsy Science Ccongress C Author(S) 2012

EPSC Abstracts Vol. 7 EPSC2012-280 2012 European Planetary Science Congress 2012 EEuropeaPn PlanetarSy Science CCongress c Author(s) 2012 A Simulation of exosphere of Ceres Ruby Lin Tu (1), Wing-Huen Ip(1,2,3) and Yung-Ching Wang (3) (1) Institute of Space Science, National Central University, Taiwan, (2) Institute of Astronomy, National Central University, Taiwan, (3) Space Science Institute, Macau University Science and Technology, Macau Abstract For the purpose of tracing the ballistic trajectories of water molecules on Ceres’ surface, we have to After Vesta, the NASA Dawn spacecraft will visit the produce a surface temperature map by omitting the largest asteroid Ceres, to carry out in-depth topographic variations and the presence of impact observations of its surface morphology and craters. Our model solves the heat conduction mineralogical composition. We examine different equation by taking account of the energy balance source mechanisms of a possible surface-bounded condition at the surface boundary and the lower exosphere composed of water molecules and other boundary condition (with dT/dz=0) into account. In species. Our preliminary assessment is that solar between the heat diffusion equation is solved by wind interaction and meteoroid impact are not using the Crank-Nicolson finite difference routine adequate because of the large injection speed of the gas at production relative to the surface escape velocity of Ceres. One potential source is a low-level (1) outgassing effect from its subsurface due to thermal sublimation. In this work, the scenario of building up a tenuous exosphere by ballistic transport and the eventual recycling of the water molecules to the polar cold trap is described. -

And Abiogenesis

Historical Development of the Distinction between Bio- and Abiogenesis. Robert B. Sheldon NASA/MSFC/NSSTC, 320 Sparkman Dr, Huntsville, AL, USA ABSTRACT Early greek philosophers laid the philosophical foundations of the distinction between bio and abiogenesis, when they debated organic and non-organic explanations for natural phenomena. Plato and Aristotle gave organic, or purpose-driven explanations for physical phenomena, whereas the materialist school of Democritus and Epicurus gave non-organic, or materialist explanations. These competing schools have alternated in popularity through history, with the present era dominated by epicurean schools of thought. Present controversies concerning evidence for exobiology and biogenesis have many aspects which reflect this millennial debate. Therefore this paper traces a selected history of this debate with some modern, 20th century developments due to quantum mechanics. It ¯nishes with an application of quantum information theory to several exobiology debates. Keywords: Biogenesis, Abiogenesis, Aristotle, Epicurus, Materialism, Information Theory 1. INTRODUCTION & ANCIENT HISTORY 1.1. Plato and Aristotle Both Plato and Aristotle believed that purpose was an essential ingredient in any scienti¯c explanation, or teleology in philosophical nomenclature. Therefore all explanations, said Aristotle, answer four basic questions: what is it made of, what does it represent, who made it, and why was it made, which have the nomenclature material, formal, e±cient and ¯nal causes.1 This aristotelean framework shaped the terms of the scienti¯c enquiry, invisibly directing greek science for over 500 years. For example, \organic" or \¯nal" causes were often deemed su±cient to explain natural phenomena, so that a rock fell when released from rest because it \desired" its own kind, the earth, over unlike elements such as air, water or ¯re. -

Ices on Mercury: Chemistry of Volatiles in Permanently Cold Areas of Mercury’S North Polar Region

Icarus 281 (2017) 19–31 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Icarus journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/icarus Ices on Mercury: Chemistry of volatiles in permanently cold areas of Mercury’s north polar region ∗ M.L. Delitsky a, , D.A. Paige b, M.A. Siegler c, E.R. Harju b,f, D. Schriver b, R.E. Johnson d, P. Travnicek e a California Specialty Engineering, Pasadena, CA b Dept of Earth, Planetary and Space Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles, CA c Planetary Science Institute, Tucson, AZ d Dept of Engineering Physics, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA e Space Sciences Laboratory, University of California, Berkeley, CA f Pasadena City College, Pasadena, CA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Observations by the MESSENGER spacecraft during its flyby and orbital observations of Mercury in 2008– Received 3 January 2016 2015 indicated the presence of cold icy materials hiding in permanently-shadowed craters in Mercury’s Revised 29 July 2016 north polar region. These icy condensed volatiles are thought to be composed of water ice and frozen Accepted 2 August 2016 organics that can persist over long geologic timescales and evolve under the influence of the Mercury Available online 4 August 2016 space environment. Polar ices never see solar photons because at such high latitudes, sunlight cannot Keywords: reach over the crater rims. The craters maintain a permanently cold environment for the ices to persist. Mercury surface ices magnetospheres However, the magnetosphere will supply a beam of ions and electrons that can reach the frozen volatiles radiolysis and induce ice chemistry. -

Water, Habitability, and Detectability Steve Desch

Water, Habitability, and Detectability Steve Desch PI, “Exoplanetary Ecosystems” NExSS team School of Earth and Space Exploration, Arizona State University with Ariel Anbar, Tessa Fisher, Steven Glaser, Hilairy Hartnett, Stephen Kane, Susanne Neuer, Cayman Unterborn, Sara Walker, Misha Zolotov Astrobiology Science Strategy NAS Committee, Beckmann Center, Irvine, CA (remotely), January 17, 2018 How to look for life on (Earth-like) exoplanets: find oxygen in their atmospheres How Earth-like must an exoplanet be for this to work? Seager et al. (2013) How to look for life on (Earth-like) exoplanets: find oxygen in their atmospheres Oxygen on Earth overwhelmingly produced by photosynthesizing life, which taps Sun’s energy and yields large disequilibrium signature. Caveats: Earth had life for billions of years without O2 in its atmosphere. First photosynthesis to evolve on Earth was anoxygenic. Many ‘false positives’ recognized because O2 has abiotic sources, esp. photolysis (Luger & Barnes 2014; Harman et al. 2015; Meadows 2017). These caveats seem like exceptions to the ‘rule’ that ‘oxygen = life’. How non-Earth-like can an exoplanet be (especially with respect to water content) before oxygen is no longer a biosignature? Part 1: How much water can terrestrial planets form with? Part 2: Are Aqua Planets or Water Worlds habitable? Can we detect life on them? Part 3: How should we look for life on exoplanets? Part 1: How much water can terrestrial planets form with? Theory says: up to hundreds of oceans’ worth of water Trappist-1 system suggests hundreds of oceans, especially around M stars Many (most?) planets may be Aqua Planets or Water Worlds How much water can terrestrial planets form with? Earth- “snow line” Standard Sun distance models of distance accretion suggest abundant water. -

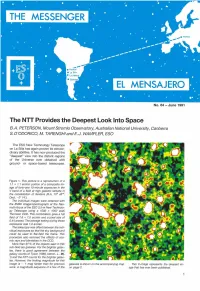

The NTT Provides the Deepest Look Into Space 6

The NTT Provides the Deepest Look Into Space 6. A. PETERSON, Mount Stromlo Observatory,Australian National University, Canberra S. D'ODORICO, M. TARENGHI and E. J. WAMPLER, ESO The ESO New Technology Telescope r on La Silla has again proven its extraor- - dinary abilities. It has now produced the "deepest" view into the distant regions of the Universe ever obtained with ground- or space-based telescopes. Figure 1 : This picture is a reproduction of a I.1 x 1.1 arcmin portion of a composite im- age of forty-one 10-minute exposures in the V band of a field at high galactic latitude in the constellation of Sextans (R.A. loh 45'7 Decl. -0' 143. The individual images were obtained with the EMMI imager/spectrograph at the Nas- myth focus of the ESO 3.5-m New Technolo- gy Telescope using a 1000 x 1000 pixel Thomson CCD. This combination gave a full field of 7.6 x 7.6 arcmin and a pixel size of 0.44 arcsec. The average seeing during these exposures was 1.0 arcsec. The telescope was offset between the indi- vidual exposures so that the sky background could be used to flat-field the frame. This procedure also removed the effects of cos- mic rays and blemishes in the CCD. More than 97% of the objects seen in this sub- field are galaxies. For the brighter galax- ies, there is good agreement between the galaxy counts of Tyson (1988, Astron. J., 96, 1) and the NTT counts for the brighter galax- ies. -

Livre-Ovni.Pdf

UN MONDE BIZARRE Le livre des étranges Objets Volants Non Identifiés Chapitre 1 Paranormal Le paranormal est un terme utilisé pour qualifier un en- mé n'est pas considéré comme paranormal par les semble de phénomènes dont les causes ou mécanismes neuroscientifiques) ; ne sont apparemment pas explicables par des lois scien- tifiques établies. Le préfixe « para » désignant quelque • Les différents moyens de communication avec les chose qui est à côté de la norme, la norme étant ici le morts : naturels (médiumnité, nécromancie) ou ar- consensus scientifique d'une époque. Un phénomène est tificiels (la transcommunication instrumentale telle qualifié de paranormal lorsqu'il ne semble pas pouvoir que les voix électroniques); être expliqué par les lois naturelles connues, laissant ain- si le champ libre à de nouvelles recherches empiriques, à • Les apparitions de l'au-delà (fantômes, revenants, des interprétations, à des suppositions et à l'imaginaire. ectoplasmes, poltergeists, etc.) ; Les initiateurs de la parapsychologie se sont donné comme objectif d'étudier d'une manière scientifique • la cryptozoologie (qui étudie l'existence d'espèce in- ce qu'ils considèrent comme des perceptions extra- connues) : classification assez injuste, car l'objet de sensorielles et de la psychokinèse. Malgré l'existence de la cryptozoologie est moins de cultiver les mythes laboratoires de parapsychologie dans certaines universi- que de chercher s’il y a ou non une espèce animale tés, notamment en Grande-Bretagne, le paranormal est inconnue réelle derrière une légende ; généralement considéré comme un sujet d'étude peu sé- rieux. Il est en revanche parfois associé a des activités • Le phénomène ovni et ses dérivés (cercle de culture). -

Biosignatures Search in Habitable Planets

galaxies Review Biosignatures Search in Habitable Planets Riccardo Claudi 1,* and Eleonora Alei 1,2 1 INAF-Astronomical Observatory of Padova, Vicolo Osservatorio, 5, 35122 Padova, Italy 2 Physics and Astronomy Department, Padova University, 35131 Padova, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 2 August 2019; Accepted: 25 September 2019; Published: 29 September 2019 Abstract: The search for life has had a new enthusiastic restart in the last two decades thanks to the large number of new worlds discovered. The about 4100 exoplanets found so far, show a large diversity of planets, from hot giants to rocky planets orbiting small and cold stars. Most of them are very different from those of the Solar System and one of the striking case is that of the super-Earths, rocky planets with masses ranging between 1 and 10 M⊕ with dimensions up to twice those of Earth. In the right environment, these planets could be the cradle of alien life that could modify the chemical composition of their atmospheres. So, the search for life signatures requires as the first step the knowledge of planet atmospheres, the main objective of future exoplanetary space explorations. Indeed, the quest for the determination of the chemical composition of those planetary atmospheres rises also more general interest than that given by the mere directory of the atmospheric compounds. It opens out to the more general speculation on what such detection might tell us about the presence of life on those planets. As, for now, we have only one example of life in the universe, we are bound to study terrestrial organisms to assess possibilities of life on other planets and guide our search for possible extinct or extant life on other planetary bodies. -

A Spitzer Space Telescope Program by Jesica Lynn Trucks

A Dissertation entitled A Variability Study of Y Dwarfs: A Spitzer Space Telescope Program by Jesica Lynn Trucks Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree in Physics with concentration in Astrophysics Dr. Michael Cushing, Committee Chair Dr. S. Thomas Megeath, Committee Member Dr. Rupali Chandar, Committee Member Dr. Richard Irving, Committee Member Dr. Stanimir Metchev, Committee Member Dr. Cyndee Gruden, Interim Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo August 2019 Copyright 2019, Jesica Lynn Trucks This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the expressed permission of the author. An Abstract of A Variability Study of Y Dwarfs: A Spitzer Space Telescope Program by Jesica Lynn Trucks Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree in Physics with concentration in Astrophysics The University of Toledo August 2019 I present the results of a search for variability in 14 Y dwarfs consisting 2 epochs of observations, each taken with Spitzer for 12 hours at [3.6] immediately followed by 12 hours at [4.5], separated by 122{464 days and found that Y dwarfs are variable. We used not only periodograms to characterize the variability but we also utilized Bayesian analysis. We found that using different methods to detect variability gives different answers making survey comparisons difficult. We determined the variability fraction of Y dwarfs to be between 37% and 74%. While the mid-infrared light curves of Y dwarfs are generally stable on time scales of months, we have encountered a few that vary dramatically on those time scales.