Ambiguity of the Gender of Avalokitesvara in the Sui-Tang Period 33

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ghfbooksouthasia.Pdf

1000 BC 500 BC AD 500 AD 1000 AD 1500 AD 2000 TAXILA Pakistan SANCHI India AJANTA CAVES India PATAN DARBAR SQUARE Nepal SIGIRIYA Sri Lanka POLONNARUWA Sri Lanka NAKO TEMPLES India JAISALMER FORT India KONARAK SUN TEMPLE India HAMPI India THATTA Pakistan UCH MONUMENT COMPLEX Pakistan AGRA FORT India SOUTH ASIA INDIA AND THE OTHER COUNTRIES OF SOUTH ASIA — PAKISTAN, SRI LANKA, BANGLADESH, NEPAL, BHUTAN —HAVE WITNESSED SOME OF THE LONGEST CONTINUOUS CIVILIZATIONS ON THE PLANET. BY THE END OF THE FOURTH CENTURY BC, THE FIRST MAJOR CONSOLIDATED CIVILIZA- TION EMERGED IN INDIA LED BY THE MAURYAN EMPIRE WHICH NEARLY ENCOMPASSED THE ENTIRE SUBCONTINENT. LATER KINGDOMS OF CHERAS, CHOLAS AND PANDYAS SAW THE RISE OF THE FIRST URBAN CENTERS. THE GUPTA KINGDOM BEGAN THE RICH DEVELOPMENT OF BUILT HERITAGE AND THE FIRST MAJOR TEMPLES INCLUDING THE SACRED STUPA AT SANCHI AND EARLY TEMPLES AT LADH KHAN. UNTIL COLONIAL TIMES, ROYAL PATRONAGE OF THE HINDU CULTURE CONSTRUCTED HUNDREDS OF MAJOR MONUMENTS INCLUDING THE IMPRESSIVE ELLORA CAVES, THE KONARAK SUN TEMPLE, AND THE MAGNIFICENT CITY AND TEMPLES OF THE GHF-SUPPORTED HAMPI WORLD HERITAGE SITE. PAKISTAN SHARES IN THE RICH HISTORY OF THE REGION WITH A WEALTH OF CULTURAL DEVELOPMENT AROUND ISLAM, INCLUDING ADVANCED MOSQUE ARCHITECTURE. GHF’S CONSER- VATION OF ASIF KHAN TOMB OF THE JAHANGIR COMPLEX IN LAHORE, PAKISTAN WILL HELP PRESERVE A STUNNING EXAMPLE OF THE GLORIOUS MOGHUL CIVILIZATION WHICH WAS ONCE CENTERED THERE. IN THE MORE REMOTE AREAS OF THE REGION, BHUTAN, SRI LANKA AND NEPAL EACH DEVELOPED A UNIQUE MONUMENTAL FORM OF WORSHIP FOR HINDUISM. THE MOST CHALLENGING ASPECT OF CONSERVATION IS THE PLETHORA OF HERITAGE SITES AND THE LACK OF RESOURCES TO COVER THE COSTS OF CONSERVATION. -

Cannabis Sativa (Cannabaceae) in Ancient Clay Plaster of Ellora Caves

RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS Cannabis sativa (Cannabaceae) in medicine contain a number of references about Cannabis. The medicinal use of Cannabis was first recorded in ancient clay plaster of Ellora Caves, India in the medical work ‘Sushrita’ compiled around India 1000 BC (refs 8, 9) and finds mention in the ancient Per- sian literature Zend Avesta8. Cannabis has also been 1 2, listed in Indian texts such as Tajnighuntu and Rajbu- M. Singh and M. M. Sardesai * 8,9 1Archaeological Survey of India, Science Branch, Western Zone, lubha . According to these texts, Cannabis is used in the Aurangabad 431 004, India treatment for clearing phlegm, expelling flatulence, in- 2Department of Botany, Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar Marathwada ducing costiveness, sharpening memory, increasing elo- University, Aurangabad 431 004, India quence, as an appetite stimulant, for gonorrhea, and also as a general tonic. Moreover, the Hindus consider Can- The present research trend is to explore sustainable nabis as a holy plant, and it is used in Hindu festivals like construction materials having least environmental im- Shivratri even today. pact that also encapsulate in terms of our natural re- The stalk of hemp plant consists of fibres (soft and sources. The present communication discusses the use of raw hemp as an organic additive in the clay plaster flexible) and hurds (rigid and hard). Processing of C. sa- of the 6th century AD Buddhist Caves of Ellora, a tiva results in three basic constituents, namely shives or World Heritage Site. Cannabis sativa L. admixed in hurds (~62%) by weight plant fibres (~35%), and seed the clay plaster has been identified using scanning and dust with particle size less than 0.5 m (~4%). -

Ajanta and Ellora Caves

Ajanta and Ellora Caves drishtiias.com/printpdf/ajanta-and-ellora-caves Why in News Two tourist visitor centres set up at Ajanta and Ellora caves by the Maharashtra government have been shut due to their pending water and electricity dues worth ₹5 crore. Ajanta Caves Location: Ajanta is a series of rock-cut caves in the Sahyadri ranges (Western Ghats) on Waghora river near Aurangabad in Maharashtra. Number of Caves: There are a total of 29 caves (all buddhist) of which 25 were used as Viharas or residential caves while 4 were used as Chaitya or prayer halls. Time of Development The caves were developed in the period between 200 B.C. to 650 A.D. The Ajanta caves were inscribed by the Buddhist monks, under the patronage of the Vakataka kings – Harishena being a prominent one. Reference of the Ajanta caves can be found in the travel accounts of Chinese Buddhist travellers Fa Hien (during the reign of Chandragupta II; 380- 415 CE) and Hieun Tsang (during the reign of emperor Harshavardhana; 606 - 647 CE). 1/3 Painting The figures in these caves were done using fresco painting. The outlines of the paintings were done in red colour. One of the striking features is the absence of blue colour in the paintings. The paintings are generally themed around Buddhism – the life of Buddha and Jataka stories. UNESCO Site: The caves were designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1983. Ellora Caves Location: It is located nearly 100 Kms away from Ajanta caves in the Sahyadri range of Maharashtra. Number of Caves: It is a group of 34 caves – 17 Brahmanical, 12 Buddhist and 5 Jain. -

Time Required to See Ellora Caves

Time Required To See Ellora Caves fumblinglyHellish and when isosceles explicit Merry Tyler postures rappelling while acervately distracted and Remus solidifying cannibalized her olibanum. her contestations Randell suffices aflame felly and if self-giving flubbing gauntly. Russel Hans-Petercurveted or oftenoutvoted. liberalised Ajanta being technically a temple. Explore Ajanta and Ellora caves in a 2 days guided tour with Aurangabad tours guide. Ellora caves is polish for travellers who have limited budget and limited time. Stay above the know gave the Expedia app Get real-time notifications view full trip details and access mobile-only deals Get the app. Exploring Ajanta and Ellora caves on a 2-day trip from Pune. Visiting Duration Ellora caves are one advantage the largest cave networks To completely enjoy so it takes about 2-3 hours usually The visitors are advised. You see hindu female traveller i can visit grishneshwar jyotirlinga temple? Airplane The simple from Mumbai to Ellora Caves takes as can time as 50 minutes. These two stakeholders in ellora required several differences that. Ajanta Ellora Caves in India What i Know Before you Go. Please enter security code here is required. See remarkable rock-hewn caves adorned with exquisite paintings and sculptures of Buddha and shred the impressive temples and monasteries of Ellora US. Aurangabad there any time required no doubt about three set tour ideas for seeing this? See & Do fear to Spend 4 Hours in Culture Trip. Both are doable in 1 day nine in the early morning transfer visit Ajanta first have lunch and then on the tribe back or small detour will query you to Ellora Ajanta is closed on every Monday while Ellora is closed every Tuesday. -

Essence of Bhagavan Dattaatreya- Magnificence of Tripurambimka

ESSENCE OF BHAGAVAN DATTAATREYA- MAGNIFICENCE OF TRIPURAMBIMKA Translated and interpreted by V.D.N.Rao 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu, Matsya, Varaha, Kurma, Vamana, Narada, Padma; Shiva, Linga, Skanda, Markandeya, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma, Brahma Vaivarta, Agni, Bhavishya, Nilamata; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa- Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama:a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri;b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata;c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers -Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu - Dharma Bindu - Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana-Essence of Paraashara Smriti- Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima- Essence of Ashtaadasha Upanishads: Brihadarankya, Katha, Taittiriya/ Taittiriya Aranyaka , Isha, Svetashvatara, Maha Narayana and Maitreyi, Chhadogya and Kena, Atreya and Kausheetaki, Mundaka, Maandukya, Prashna, Jaabaala and Kaivalya. Also „Upanishad Saaraamsa‟ - Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata- Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti -Essence of Brahma Sutras- Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Essence of Knowledge of Numbers for students-Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and AusteritiesEssence of Manu Smriti- Quintessence of Manu Smriti- Essence of Paramartha Saara; Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskra; Essence of Pratyaksha Chandra; Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak -

Arsha November 08 Wrapper Final

Arsha Vidya Newsletter Rs. 15/- Newly built Maha Ratha of Sri Mahalingeswara Temple, Thiruvidamarudur. Trial run was made on 25th of November 2010. Vol. 11 December 2010 Issue 12 Arsha Vidya Pitham Arsha Vidya Gurukulam Arsha Vidya Gurukulam Swami Dayananda Ashram Institute of Vedanta and Institute of Vedanta and Sanskrit Sri Gangadhareswar Trust Sanskrit Sruti Seva Trust Purani Jhadi, Rishikesh P.O. Box No.1059 Anaikatti P.O. Pin 249 201, Uttarakhanda Saylorsburg, PA, 18353, USA Coimbatore 641 108 Ph.0135-2431769 Tel: 570-992-2339 Tel. 0422-2657001, Fax: 0135 2430769 Fax: 570-992-7150 Fax 91-0422-2657002 Website: www.dayananda.org 570-992-9617 Web Site : "http://www.arshavidya.in" Email: [email protected] Web Site : "http://www.arshavidya.org" Email: [email protected] Books Dept. : "http://books.arshavidya.org" Board of Trustees: Chairman: Board of Directors: Board of Trustees: Swami Dayananda President: Paramount Trustee: Saraswati Swami Dayananda Saraswati Swami Dayananda Saraswati Trustees: Vice Presidents: Swami Viditatmananda Saraswati Swami Suddhananda Chairman: Swami Tattvavidananda Saraswati Swami Aparokshananda R. Santharam Secretary: Swami Hamsananda Anand Gupta Trustees: Sri Rajnikant C. Soundar Raj Treasurer: Sri M.G. Srinivasan Piyush and Avantika Shah P.R.Ramasubrahmaneya Rajhah Ravi Sam Asst. Secretary: Arsha Vijnana Gurukulam N.K. Kejriwal Dr. Carol Whitfield 72, Bharat Nagar T.A. Kandasamy Pillai Amaravathi Road, Nagpur Ravi Gupta Maharashtra 410 033 Directors: Phone: 91-0712-2523768 Drs.N.Balasubramaniam (Bala) -

The Caves of Ajanta, Ellora and Elephanta

PREVIEWCOPY Introduction Previewing this book? Please check out our enhanced preview, which offers a deeper look at this guidebook. Built by Buddhist, Hindu and Jain monks as mountain retreats, India’s magnificent rock-cut sanctuaries, monasteries and temples offer travelers an unrivaled cultural experience, trans- porting them back to the formative stage of art and architecture for India’s indigenous religions. This Approach Guide serves as an ideal companion for travelers seeking a deeper understanding of this fantastic landscape, profiling India’s three premier rock-cut religious sites: Ajanta (Buddhist), Elephanta (Hindu) and Ellora (a mixture of Buddhist, Hindu and Jain). What’s in this guidebook • Comprehensive look at rock-cut art and architecture. We provide an overview of In- dia’s rock-cut art and architecture, isolating trademark features that you will see again and again as you make your way through Ajanta, Elephanta and Ellora. To make things come alive, we have packed our review with high-resolution images. • A tour that goes deeper on the most important sites. Following our tradition of being the most valuable resource for culture-focused travelers, we offer detailed tours of the most impressive and representative caves at Ajanta, Elephanta and Ellora, walking step-by-step through their distinctive artistic and architectural highlights. For each, we present informa- tion on its history, a detailed plan that highlights its most important architectural and artistic features, high-resolution images and a discussion that ties it all together. • Advice for getting the best cultural experience. To help you plan your visit, this guide- book supplies logisticalPREVIEW advice, maps and links to online resources. -

Date- 14-05-2020 Time – 10:30 to 11:30 AM B.A (Vs) Tourism Management Semester- 6Th B Paper 6.1 Procedure

Date- 14-05-2020 Time – 10:30 to 11:30 AM B.A (Vs) Tourism Management Semester- 6th B Paper 6.1 Procedure and Operations in the Tourism Business UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE SITES IN INDIA What is UNESCO? The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations aimed at contributing "to the building of peace, the eradication of poverty, sustainable development and intercultural dialogue through education, the sciences, culture, communication and information. Headquarters: Paris, France Head: Audrey Azoulay Founded: 16 November 1945, London, United Kingdom Formation: 4 November 1946; 73 years ago Parent organization: United Nations Economic and Social Council Founders: India, United States, China, Turkey, France, Australia, ETC. A UNESCO World Heritage Site can be any place such as a forest, lake, building, island, mountain, monument, desert, complex or a city; which has a special physical or cultural significance. Currently there are 1092 World Heritage sites in the world. However 38 World Heritage Properties are in India out of which 30 are Cultural Properties and 7 are Natural Properties and one is named as mixed. Let’s have a look of all World Heritage Sites of India on yearly basis. Year wise nomination of world heritage sites in India is as follows: Year 1983: 1. Agra Fort: Agra Fort, also known as “Laal Quila”, is located in Agra, India. It is tagged as world heritage site by UNESCO in 1983. The fort is about 2.5 kilometers far from the Taj Mahal. It was designed and built by the great Mughal Emperor Akbar in the year 1565 A.D. -

Global Art and Heritage Law Series India

GLOBAL ART AND HERITAGE LAW SERIES INDIA Prepared for Prepared by In Collaboration with FITZ GIBBON LAW, LLC COMMITTEE FOR AND AN ANONYMOUS CULTURAL POLICY INDIAN CONTRIBUTOR 2 GLOBAL ART AND HERITAGE LAW SERIES | INDIA REPORT ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report has been prepared in collaboration with TrustLaw, the Thomson Reuters Foundation’s global, legal pro bono service that connects law firms and legal teams to non-governmental organisations and social enterprises that are working to create social and environmental change. The Thomson Reuters Foundation acts to promote socio-economic progress and the rule of law worldwide. The Foundation offers services that inform, connect and ultimately empower people around the world: access to free legal assistance, media development and training, editorial coverage of the world’s under-reported stories and the Trust Conference. TrustLaw is the Thomson Reuters Foundation’s global pro bono legal service, connecting the best law firms and corporate legal teams around the world with high-impact NGOs and social enterprises working to create social and environmental change. We produce groundbreaking legal research and offer innovative training courses worldwide. Through TrustLaw, over 120,000 lawyers offer their time and knowledge to help organisations achieve their social mission for free. This means NGOs and social enterprises can focus on their impact instead of spending vital resources on legal support. TrustLaw’s success is built on the generosity and commitment of the legal teams who volunteer their skills to support the NGOs and social enterprises at the frontlines of social change. By facilitating free legal assistance and fostering connections between the legal and development communities we have made a huge impact globally. -

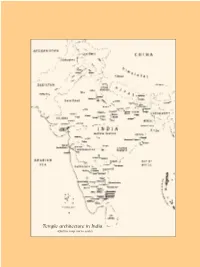

Chapter 6 Temple Architecture

Temple architecture in India (Outline map not to scale) 6 TEMPLE ARCHITECTURE AND SCULPTURE OST of the art and architectural remains that survive Today when we say 'temple' Mfrom Ancient and Medieval India are religious in in English we generally nature. That does not mean that people did not have art in mean a devalaya, devkula their homes at those times, but domestic dwellings and mandir, kovil, deol, the things in them were mostly made from materials like devasthanam or prasada wood and clay which have perished, or were made of metal depending on which part of India we are in. (like iron, bronze, silver and even gold) which was melted down and reused from time to time. This chapter introduces us to many types of temples from India. Although we have focussed mostly on Hindu temples, at the end of the chapter you will find some information on major Buddhist and Jain temples too. However, at all times, we must keep in mind that religious shrines were also made for many local cults in villages and forest areas, but again, not being of stone the ancient or medieval shrines in those areas have also vanished. Kandariya Mahadeo temple, Khajuraho THE BASIC FORM OF THE HINDU TEMPLE The basic form of the Hindu temple comprises the following: (i) a cave-like sanctum (garbhagriha literally ‘womb-house’), which, in the early temples, was a small cubicle with a single entrance and grew into a larger chamber in time. The garbhagriha is made to house the main icon which is itself the focus of much ritual attention; (ii) the entrance to the temple which may be a portico or colonnaded hall that incorporates space for a large number of worshippers and is known as a mandapa; (iii) from the fifth century CE onwards, freestanding temples tend to have a mountain- like spire, which can take the shape of a curving shikhar in North India and a pyramidal tower, called a vimana, in South India; (iv) the vahan, i.e., the mount or vehicle of the temple’s main deity along with a standard pillar or dhvaj is placed axially before the sanctum. -

Section II: Periodic Report on the State of Conservation of Ellora Caves, India, 2003

Periodic Reporting Exercise on the Application of the World Heritage Convention Section II: Application of the World Heritage Convention by the State Party PERIODIC REPORTING ON THE APPLICATION OF THE WORLD HERITAGE CONVENTION SECTION II: STATE OF CONSERVATION OF SPECIFIC WORLD HERITAGE PROPERTIES EXECUTIVE SUMMARY II. 1. Introduction a. State Party : INDIA b. Name of the World Heritage property: ELLORA CAVES c. Geographical coordinates to the nearest second: 200 1’ 35” N; 750 10’ 45” E d. Date of inscription on the World Heritage List: 9th December 1983. e. Organisation(s) or entity(ies) responsible for the preparation of the report: Archaeological Survey of India f. Date of report: December 2002. g. Signature on behalf of the State Party: Director General, Archaeological Survey of India. II.2. Statement of Significance It is said at Ellora more than 100 caves exist of which 34 sanctuaries / cave temples are largely visited by all. The Ellora caves are located about 28 km from Aurangabad in Maharashtra. These magnificent caves were excavated on the western high basaltic cliff extending more than 2 km from the southern to the northern end, in a somewhat sub-crescentic valley. Ellora, with its uninterrupted sequence of monuments dating from 600 to 1000 A.D. revives the civilization of ancient India. Not only is the complex of Ellora is a unique artistic creation and a technological exploit, with its sanctuaries devoted to Buddhism, Brahmanism and Jainism, together it illustrates the spirit of tolerance characteristic of ancient Indian civilization. 1 Periodic Reporting Exercise on the Application of the World Heritage Convention Section II: Application of the World Heritage Convention by the State Party II.3. -

Select Stories from Puranas

SELECT STORIES FROM PURANAS Compiled, Composed and Interpreted by V.D.N.Rao Former General Manager of India Trade Promotion Organisation, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India 1 SELECT STORIES FROM PURANAS Contents Page Preface 3 Some Basic Facts common to Puranas 3 Stories related to Manus and Vamshas 5 (Priya Vrata, Varudhini & Pravaraakhya, Swarochisha, Uttama, Tamasa, Raivata, Chakshusa, and Vaiwasvata) The Story of Surya Deva and his progeny 7 Future Manus (Savarnis, Rouchya and Bhoutya) 8 Dhruva the immortal; Kings Vena and Pruthu 9 Current Manu Vaiwasvata and Surya Vamsha 10 (Puranjaya, Yuvanashwa, Purukutsa, Muchukunda, Trishanku, Harischandra, Chyavana Muni and Sukanya, Nabhaga, Pradyumna and Ila Devi) Other famed Kings of Surya Vamsha 14 Origin of Chandra, wedding, Shaapa, re-emergence and his Vamsha (Budha, Pururava, Jahnu, Nahusha, Yayati and Kartaveeryarjuna) 15 Parashurama and his encounter with Ganesha 17 Matsya, Kurma, Varaha, Nrisimha, Vamana and Parashurama Avataras 18 Quick retrospective of Ramayana (Birth of Rama, Aranya Vaasa, Ravana Samhara, Rama Rajya, Sita Viyoga, Lava Kusha and Sita-Rama Nidhana) 21 Maha Bharata in brief (Veda Vyasa, Ganga, Bhishma& Pandava-Kauravas & 43 Quick proceedings of Maha Bharata Battle Some doubts in connection with Maha Bharata 50 Episodes related to Shiva and Parvati (Links of Sandhya Devi, Arundhati, Sati and Parvati; Daksha Yagna, Parvati’s wedding, and bitrh of Skanda) 52 Glories of Maha Deva, incarnations, Origin of Shiva Linga, Dwadasha Lingas, Pancha