8-Temple-Architecture.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

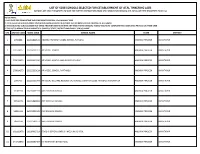

List of 6038 Schools Selected for Establishment of Atal Tinkering

LIST OF 6038 SCHOOLS SELECTED FOR ESTABLISHMENT OF ATAL TINKERING LABS (SCHOOLS ARE KINDLY REQUESTED TO WAIT FOR FURTHER INSTRUCTIONS FROM ATAL INNOVATION MISSION, NITI AAYOG ON THEIR REGISTERED EMAIL IDs) PLEASE NOTE:- 1. LAST DATE FOR COMPLETING THE COMPLIANCE PROCESS : 31st JANUARY 2020 2. THESE SELECTED SCHOOLS MUST OPEN A NEW BANK ACCOUNT IN A PUBLIC SECTOR BANK FOR THE PURPOSE OF ATL GRANT. 3. THESE SELECTED SCHOOLS MUST NOT SHARE THEIR INFORMATION WITH ANY THIRD PARTY/ VENDOR/ AGENT/ AND MUST COMPLETE THE COMPLIANCE PROCESS ON THEIR OWN. 4. THIS LIST IS ARRANGED IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER OF STATE, DISTRICT AND FINALLY SCHOOL NAME. S.N. ATL UID CODE UDISE CODE SCHOOL NAME STATE DISTRICT 1 2760806 28222800515 ANDHRA PRADESH MODEL SCHOOL PUTLURU ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 2 132314217 28224201013 AP MODEL SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 3 574614473 28223600320 AP MODEL SCHOOL AND JUNIOR COLLEGE ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 4 278814373 28223200124 AP MODEL SCHOOL RAPTHADU ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 5 2995459 28222500704 AP SOCIAL WELFARE RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL JUNIOR COLLEGE FOR GIRLS KURUGUNTA ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 6 13701194 28220601919 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 7 15712075 28221890982 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 8 56051196 28222301035 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 9 385c1160 28221591153 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 10 102112978 28220902023 GOOD SHEPHERD ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 11 243715046 28220590484 K C NARAYANA E M SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR LIST OF 6038 SCHOOLS SELECTED FOR ESTABLISHMENT OF ATAL TINKERING LABS (SCHOOLS ARE KINDLY REQUESTED TO WAIT FOR FURTHER INSTRUCTIONS FROM ATAL INNOVATION MISSION, NITI AAYOG ON THEIR REGISTERED EMAIL IDs) PLEASE NOTE:- 1. -

Construction Techniques of Indian Temples

International Journal of Research in Engineering, Science and Management 420 Volume-1, Issue-10, October-2018 www.ijresm.com | ISSN (Online): 2581-5782 Construction Techniques of Indian Temples Chanchal Batham1, Aatmika Rathore2, Shivani Tandon3 1,3Student, Department of Architecture, SDPS Women’s College, Indore, India 2Assistant Professor, Department of Architecture, SDPS Women’s College, Indore, India Abstract—India is a country of temples. Indian temples, which two principle axis, which in turn resulted in simple structural are standing with an unmatched beauty and grandeur in the wake systems and an increased structural strength against seismic of time against the forces of nature, are the living evidences of forces. The Indian doctrine of proportions is designed not only structural efficiency and technological skill of Indian craftsman to correlate the various parts of building in an aesthetically and master builders. Every style of building construction reflects pleasing manner but also to bring the entire building into a a clearly distinctive basic principle that represents a particular culture and era. In this context the Indian Hindu temple magical harmony with the space. architecture are not only the abode of God and place of worship, B. Strutural Plan Density but they are also the cradle of knowledge, art, architecture and culture. The research paper describes the analysis of intrinsic Structural plan density defined as the total area of all vertical qualities, constructional and technological aspects of Indian structural members divided by the gross floor area. The size and Temples from any natural calamities. The analytical research density of structural elements is very great in the Indian temples highlights architectural form and proportion of Indian Temple, as compared to the today's buildings. -

General Introduction to Odishan Temple Architecture

Odisha Review May - 2012 General introduction to Odishan Temple Architecture Anjaliprava Sahoo INTRODUCTION Sastras recognize three main styles of temple architecture known as the Nagara, the Dravida Temple is a ‘Place of Worship’. It is also called 1 the ‘House of God’. Stella Kramrisch has defined and the Vesara. temple as ‘Monument of Manifestation’ in her NAGARA TEMPLE STYLE book ‘The Hindu Temple’. The temple is one of Nagara types of temples are the typical the prominent and enduring symbols of Indian Northern Indian temples with curvilinear sikhara- culture: it is the most graphic expression of religious spire topped by amlakasila.2 This style was fervour, metaphysical values and aesthetic developed during A.D. 5th century. The Nagara aspiration. style is characterized by a beehive-shaped and The idea of temple originated centuries multi-layered tower, called ‘Sikhara’. The layers ago in the universal ancient conception of God in of this tower are topped by a large round cushion- a human form, which required a habitation, a like element called ‘amlaka’. The plan is based shelter and this requirement resulted in a structural on a square but the walls are sometimes so shrine. India’s temple architecture is developed segmented, that the tower appears circular in from the Sthapati’s and Silpi’s creativity. A small shape. Advancement in the architecture is found Hindu temple consists of an inner sanctum, the in temples belonging to later periods, in which the Garbha Griha or womb chamber; a small square central shaft is surrounded by many smaller room with completely plain walls having a single narrow doorway in the front, inside which the image is housed and other chambers which are varied from region to region according to the needs of the rituals. -

Ghfbooksouthasia.Pdf

1000 BC 500 BC AD 500 AD 1000 AD 1500 AD 2000 TAXILA Pakistan SANCHI India AJANTA CAVES India PATAN DARBAR SQUARE Nepal SIGIRIYA Sri Lanka POLONNARUWA Sri Lanka NAKO TEMPLES India JAISALMER FORT India KONARAK SUN TEMPLE India HAMPI India THATTA Pakistan UCH MONUMENT COMPLEX Pakistan AGRA FORT India SOUTH ASIA INDIA AND THE OTHER COUNTRIES OF SOUTH ASIA — PAKISTAN, SRI LANKA, BANGLADESH, NEPAL, BHUTAN —HAVE WITNESSED SOME OF THE LONGEST CONTINUOUS CIVILIZATIONS ON THE PLANET. BY THE END OF THE FOURTH CENTURY BC, THE FIRST MAJOR CONSOLIDATED CIVILIZA- TION EMERGED IN INDIA LED BY THE MAURYAN EMPIRE WHICH NEARLY ENCOMPASSED THE ENTIRE SUBCONTINENT. LATER KINGDOMS OF CHERAS, CHOLAS AND PANDYAS SAW THE RISE OF THE FIRST URBAN CENTERS. THE GUPTA KINGDOM BEGAN THE RICH DEVELOPMENT OF BUILT HERITAGE AND THE FIRST MAJOR TEMPLES INCLUDING THE SACRED STUPA AT SANCHI AND EARLY TEMPLES AT LADH KHAN. UNTIL COLONIAL TIMES, ROYAL PATRONAGE OF THE HINDU CULTURE CONSTRUCTED HUNDREDS OF MAJOR MONUMENTS INCLUDING THE IMPRESSIVE ELLORA CAVES, THE KONARAK SUN TEMPLE, AND THE MAGNIFICENT CITY AND TEMPLES OF THE GHF-SUPPORTED HAMPI WORLD HERITAGE SITE. PAKISTAN SHARES IN THE RICH HISTORY OF THE REGION WITH A WEALTH OF CULTURAL DEVELOPMENT AROUND ISLAM, INCLUDING ADVANCED MOSQUE ARCHITECTURE. GHF’S CONSER- VATION OF ASIF KHAN TOMB OF THE JAHANGIR COMPLEX IN LAHORE, PAKISTAN WILL HELP PRESERVE A STUNNING EXAMPLE OF THE GLORIOUS MOGHUL CIVILIZATION WHICH WAS ONCE CENTERED THERE. IN THE MORE REMOTE AREAS OF THE REGION, BHUTAN, SRI LANKA AND NEPAL EACH DEVELOPED A UNIQUE MONUMENTAL FORM OF WORSHIP FOR HINDUISM. THE MOST CHALLENGING ASPECT OF CONSERVATION IS THE PLETHORA OF HERITAGE SITES AND THE LACK OF RESOURCES TO COVER THE COSTS OF CONSERVATION. -

PPT 1 Land of Gods

TURE EN TO V UR D S A www.freedomriderss.com LAND OF GODS Best Time : March - April September to November RIDE.EXPLORE.ADVENTURE Explore the most beautiful rides in India, with Royal Enfield, which is just not a motorcycle it’s a history. Experience a motorcycle TRIP through the Mystic Himalayas with majestic Views and Breathtaking Scenery. Everything from adventure experience, to relaxing motorcycle holidays. Day 1 - Jim Corbett Riders will depart from Delhi in an AC Coach on a 4-6 hour drive to Jim Corbett National Park, One of the oldest Safari Parks in World, Residing on the Foothills of Himalayas This Park has some great Forest Views and superb Wildlife Around including Wild Elephants, Tigers, Rhinos and many other Himlayan Birds. After lunch we'll gather to inspect our Royal Enfield motorcycles, and head out on a casual ride through the surroundings of the National Park and Get Use to the Bikes. Day 2 - Jim Corbett to Kasar Devi 216 Kms - Riding Time 6 to 7 hours Ride through breath-taking landscapes of the Himalayan Region. Kasar Devi is Small Ancient Temple village located in Himalayas. It offers great views of snow capped peaks and Himalayan Forests. Spend a night in magnificent Retreat in the lap of Himalayas. Day 3 - Kasar Devi To Munsiyari 189 Kms - Riding Time 6 to 7 hours Ride to Munsiyari, a beautiful little village in the lap of Himalayas offering the great views of panchkula Ranges in Himalayas. This is practically the Last Village on the Indian Borders. Enjoy the Local traditons of Kumaon Ranges and Visit the Himalayan Hot Springs This is going to be the Highest Village We will visit on our Ride, Its located at height of 2300 metres in Himalayan Region. -

State District Branch Address Centre Ifsc Contact1 Contact2 Contact3 Micr Code

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE ANDAMAN 98, MAULANA AZAD AND Andaman & ROAD, PORT BLAIR, NICOBAR Nicobar State 744101, ANDAMAN & 943428146 ISLAND ANDAMAN Coop Bank Ltd NICOBAR ISLAND PORT BLAIR HDFC0CANSCB 0 - 744656002 HDFC BANK LTD. 201, MAHATMA ANDAMAN GANDHI ROAD, AND JUNGLIGHAT, PORT NICOBAR BLAIR ANDAMAN & 98153 ISLAND ANDAMAN PORT BLAIR NICOBAR 744103 PORT BLAIR HDFC0001994 31111 ANDHRA HDFC BANK LTD6-2- 022- PRADESH ADILABAD ADILABAD 57,CINEMA ROAD ADILABAD HDFC0001621 61606161 SURVEY NO.109 5 PLOT NO. 506 28-3- 100 BELLAMPALLI ANDHRA ANDHRA PRADESH BELLAMPAL 99359 PRADESH ADILABAD BELLAMPALLI 504251 LI HDFC0002603 03333 NO. 6-108/5, OPP. VAGHESHWARA JUNIOR COLLEGE, BEAT BAZAR, ANDHRA LAXITTIPET ANDHRA LAKSHATHI 99494 PRADESH ADILABAD LAXITTIPET PRADESH 504215 PET HDFC0003036 93333 - 504240242 18-6-49, AMBEDKAR CHOWK, MUKHARAM PLAZA, NH-16, CHENNUR ROAD, MANCHERIAL - MANCHERIAL ANDHRA ANDHRA ANDHRA PRADESH MANCHERIY 98982 PRADESH ADILABAD PRADESH 504208 AL HDFC0000743 71111 NO.1-2-69/2, NH-7, OPPOSITE NIRMAL ANDHRA BUS DEPO, NIRMAL 98153 PRADESH ADILABAD NIRMAL PIN 504106 NIRMAL HDFC0002044 31111 #5-495,496,Gayatri Towers,Iqbal Ahmmad Ngr,New MRO Office- THE GAYATRI Opp ANDHRA CO-OP URBAN Strt,Vill&Mdl:Mancheri MANCHERIY 924894522 PRADESH ADILABAD BANK LTD al:Adilabad.A.P AL HDFC0CTGB05 2 - 504846202 ANDHRA Universal Coop Vysya Bank Road, MANCHERIY 738203026 PRADESH ADILABAD Urban Bank Ltd Mancherial-504208 AL HDFC0CUCUB9 1 - 504813202 11-129, SREE BALAJI ANANTHAPUR - RESIDENCY,SUBHAS -

Ahimsa and Vegetarianism

March , 2015 Vol. No. 176 Ahimsa Times in World Over + 100000 The Only Jain E-Magazine Community Service for 14 Continuous Years Readership AHIMSA AND VEGETARIANISM MAHARASHTRA GOVERNMENT BANS COW SLAUGHTER: FIVE YEARS JAIL Mar. 3rd, 2015. Mumbai. The bill banning cow slaughter in Maharashtra, pending for several years, finally received the President's assent, which means red meat lovers in the state will have to do without beef. This measure has taken almost twenty years to materialize and was initiated during the previous Sena-BJP Government. The bill was first submitted to the President for approval on January 30, 1996.. However, subsequent Governments at the Centre, including the BJP led NDA stalled it and did not seek the President’s consent. A delegation of seven state BJP MPs led by Kirit Somaiya, (MP from Mumbai North) had met the President in New Delhi recently and submitted a memorandum seeking assent to the bill. The memorandum said that the Maharashtra Animal Preservation (Amendment) Bill, 1995, passed during the previous Shiv Sena-BJP regime, was pending for approval for 19 years. The law will ban beef from the slaughter of bulls and bullocks, which was previously allowed based on a fit- for-slaughter certificate. The new Act will, however, allow the slaughter of water buffaloes. The punishment for the sale of beef or possession of it could be prison for five years with an additional fine of Rs 10,000. It is notable that, Reuters new service had earlier reported that Hindu nationalists in India had stepped up attacks on the country's beef industry, seizing trucks with cattle bound for abattoirs and blockading meat processing plants in a bid to halt the trade in the world's second-biggest exporter of beef. -

Sun Worship in Himalaya Region: with Special Reference to Katarmal and Martand

Artistic Narration: A Peer Reviewed Journal of Visual & Performing Art ISSN (P): 0976-7444 Vol. IV., 2013 Sun Worship in Himalaya Region: with Special Reference to Katarmal and Martand Dr. Virendra Bangroo Assistant Professor IGNCA, New Delhi. & Dr. Richan Kamboj Assistant Professor & HOD, Department of Drawing & Painting M.K.P.(P.G.) College Dehra Dun. The Sun, the source of light and solar energy, is the sources of all life and finds mention in all the sacred texts like the Rig Veda, the Vishnu Purana, the Mahabharta, the Bhavisya Purana, the Chandogya Upanishad, the Markandaya Purana, the Taittiriya Upansihad, the Nilarudra Upanishad and the Varaha purana. The Sun or Surya is also known by other names, each name highlights the grandeur, brilliance, quality and power of the Sun,viz:- 1. Aditya- Son of the primordial vastness ss 2. Aja-ekapad – one legged goat 3. Pavaka – Purifier 4. Jivana- the source of life 5. Jayanta-Victorious 6. Ravi - Divider 7. Martanda- born from life less egg 8. Savitr -Nourisher 9. Aharpati-Lord of the day 10. Jagat chaksu-Eye of the world 11 - Karma Sanskasin -Witness of deeds 12. Graha Rajan-King of Planets 13. Sahasra-Kirana-Having Thousand beams 14. Saptashwa-Having seven horses 15. Dyumani-Gem of the sky 1 Artistic Narration: A Peer Reviewed Journal of Visual & Performing Art ISSN (P): 0976-7444 Vol. IV., 2013 16. Graha pati-Lord of the Planets 17. Heli-Pervader 18. Khaga-Wanderer of space 19. Padma-bandhu-Friend of the lotus 20. Padma Pani-Lotus in hand 21. Himarati- Enemy of snow 22. -

Folklore Foundation , Lokaratna ,Volume IV 2011

FOLKLORE FOUNDATION ,LOKARATNA ,VOLUME IV 2011 VOLUME IV 2011 Lokaratna Volume IV tradition of Odisha for a wider readership. Any scholar across the globe interested to contribute on any Lokaratna is the e-journal of the aspect of folklore is welcome. This Folklore Foundation, Orissa, and volume represents the articles on Bhubaneswar. The purpose of the performing arts, gender, culture and journal is to explore the rich cultural education, religious studies. Folklore Foundation President: Sri Sukant Mishra Managing Trustee and Director: Dr M K Mishra Trustee: Sri Sapan K Prusty Trustee: Sri Durga Prasanna Layak Lokaratna is the official journal of the Folklore Foundation, located in Bhubaneswar, Orissa. Lokaratna is a peer-reviewed academic journal in Oriya and English. The objectives of the journal are: To invite writers and scholars to contribute their valuable research papers on any aspect of Odishan Folklore either in English or in Oriya. They should be based on the theory and methodology of folklore research and on empirical studies with substantial field work. To publish seminal articles written by senior scholars on Odia Folklore, making them available from the original sources. To present lives of folklorists, outlining their substantial contribution to Folklore To publish book reviews, field work reports, descriptions of research projects and announcements for seminars and workshops. To present interviews with eminent folklorists in India and abroad. Any new idea that would enrich this folklore research journal is Welcome. -

Sonagiri: Steeped in Faith

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S Datia Palace: Forgotten Marvel of Bundelkhand Sonagiri: Steeped in Faith Dashavatar Temple: A Gupta-Era Wonder Deogarh’s Buddhist Caves Chanderi and its weaves The Beauty of Shivpuri Kalpi – A historic town I N T R O D U C T I O N Jhansi city also serves as a perfect base for day trips to visit the historic region around it. To the west of Jhansi lies the city of Datia, known for the beautiful palace built by Bundela ruler Bir Singh Ju Dev and the splendid Jain temple complex known as Sonagir. To the south, in the Lalitpur district of Uttar Pradesh lies Deogarh, one of the most important sites of ancient India. Here lies the famous Dashavatar temple, cluster of Jain temples as well as hidden Buddhist caves by the Betwa river, dating as early as 5th century BCE. Beyond Deogarh lies Chanderi , one of the most magnificent forts in India. The town is also famous for its beautiful weave and its Chanderi sarees. D A T I A P A L A C E Forgotten Marvel of Bundelkhand The spectacular Datia Palace, in Datia District of Madhya Pradesh, is one of the finest examples of Bundelkhand architecture that arose in the late 16th and early 17th centuries in the region under the Bundela Rajputs. Did you know that this palace even inspired Sir Edward Lutyens, the chief architect of New Delhi? Popularly known as ‘Govind Mahal’ or ‘Govind Mandir’ by local residents, the palace was built by the powerful ruler of Orchha, Bir Singh Ju Dev (r. -

Dasavatara in Puranas

Component-I (A) – Personal details: Prof. P. Bhaskar Reddy Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati. Prof. V. Venkata Ramana Reddy Director, O.R.I., S. V.University, Tirupati. Prof. V. Venkata Ramana Reddy Director, O.R.I., S. V.University, Tirupati. Prof. V. Kannan University of Hyderabad, Hyderabad. Component-I (B) – Description of module: Subject Name Indian Culture Paper Name Vedic, Epic and Puranic culture of India Module Name/Title Dasavatara in Puranas Module Id I C / VEPC / 33 Pre requisites Knowledge in Puranas and importance of Dashavataras of Vishnu To know about the general survey of Puranas, Objectives Meaning of Dashavatara, Types of Incarnation Dashavatara, Scientific analogy of Avataras and Darwinian Theory of Evolution Keywords Puranas / Dashavatara / incarnation / Vishnu E-text (Quadrant-I): 1. Introduction to Avatara(Incornation) The word 'avatara' means 'one who descends' (from Sanskrit avatarati). The descents of Vishnu from Vaikuntha to earth are his avatars or incarnations. The form in each time he descents will be different because the needs of the world each time are different. The different avatars thus balances and reinforce the dharma that rules and regulations that maintain order. They are harmed when the demands of evil clash with the good for order. As man's understanding of the world changes, desires change and so do concepts of order.. Social stability and peace on the earth must not be compromised, yet new ideas that are good for mankind must be respected. Vishnu's descents are not just about The word specifically refers to one who descends from the spiritual sky. The word 'incarnation' is can also mean as 'one who assumed flesh body’ 2. -

49107-003: Tamil Nadu Urban Flagship Investment Program

Environmental Assessment and Review Framework Document Stage: Draft for consultation Project Number: 49107-003 May 2018 IND: Tamil Nadu Urban Flagship Investment Program Prepared by Tamil Nadu Urban Infrastructure Financial Services Limited of the Government of Tamil Nadu for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 11 May 2018) Currency Unit – Indian rupee (₹) ₹1.00 = $0.015 $1.00 = ₹67.09 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank ASI – Archaeological Survey of India CMA – Commissioner of Municipal Administration CMSC – construction management and supervision consultant CMWSSB – Chennai Water Supply and Sewerage Board CPCB – Central Pollution Control Board CRZ – Coastal Regulation Zone CTE – consent to establish CTO – consent to operate DPR – detailed project report EAC – expert appraisal committee EAR – environmental assessment report EARF – environmental assessment and review framework ECSMF – environmental, climate change and social management framework EHS – environment, health and safety EIA – environmental impact assessment EMP – environmental management plan ESF – environmental and social framework ESMF – environmental and social management framework ESS – environmental and social safeguard ESZ – eco sensitive zone GOTN – Government of Tamil Nadu IEE – initial environmental examination IUCN – International Union for Conservation of Nature MAWS – Municipal Administration and Water Supply MFF – multitrance financing facility MOEFCC – Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change NEP – National Environment Policy