Fermented Meat Sausages and the Challenge of Their Plant-Based

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clean Lean Protein Technical Bulletin

SEPT 2015 CLEAN LEAN PROTEIN TECHNICAL BULLETIN ULTRA-HIGH BIOLOGICAL VALUE GOLDEN PEA PROTEIN, ALKALINE, NO ADDED MALTODEXTRIN, LACTOSE, POLYOLS OR FODMAPS All 9 essential amino acids. High glutamine. Very low carbs and low fat. No fillers, no artificial additives, preservatives, sweeteners, flavours or colours DISCLAIMER For educational and informational use by practitioners and businesses only The information in this Technical Bulletin is intended exclusively for business- to-business use, and not for the end consumer. The Technical Bulletin has been compiled independently by ANH Consultancy Ltd (The Atrium, Curtis Road, Dorking, Surrey RH4 1XA, UK) to provide education and information specifically for qualified healthcare practitioners, retailers and sport and fitness professionals with interests in the NuZest product range or ingredients contained within it. Accordingly, NuZest can accept no responsibility for the quality or accuracy of the material contained herein. The information and any implied health claims made are not necessarily authorised by national or EU authorities for communication to the end consumer. GLUTEN FREE • DAIRY FREE • LECTIN FREE • SOY FREE • GMO FREE T 1300 575 121 W nuzest.com.au E [email protected] facebook.com/nuzest.aus NUZEST CLEAN LEAN PROTEIN CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION & PRODUCT JUSTIFICATION 2 PEA PROTEIN ISOLATE 3 NUTRITIONAL PROFILE 4 MANAGING THE BODY’S AMINO ACID POOL 6 SUPPORTING ATHLETES & ACTIVE LIFESTYLES 8 WHAT’S IN CLEAN LEAN PROTEIN? 10 CLEAN LEAN PROTEIN 11 REFERENCES 12 T 1300 575 121 W nuzest.com.au E [email protected] facebook.com/nuzest.aus INTRODUCTION & PRODUCT JUSTIFICATION 2 NUZEST’S CLEAN LEAN PROTEIN (CLP) IS A UNIQUE, VEGETARIAN AND VEGAN, PROTEIN CHARACTERISED BY ITS TASTE (4 NATURAL FLAVOURS AND AN UNFLAVOURED), LACK OF FILLERS OR FOOD ADDITIVES, AND VERY HIGH DIGESTIBILITY. -

Nutrition & Supplements Catalog

2 019 — 2020 But wait, there’s MORE! We can’t publish all our items in one catalog—it takes SIX catalogs! Find details about the different AZURE STANDARD catalogs we offer throughout AzureStandard.com the year on page 2. Nutrition & Supplements Catalog 971-200-8350 | 971-200-8350 Nutrition & Supplements THE ITEMS IN THIS CATALOG meet a high threshold for quality. Azure requires transparency from all the companies we work with, and we only choose suppliers that produce real foods made with only natural ingredients. That means you get nutrient-rich foods that are minimally processed with no artificial additives, no preservatives, non-GMO, no MSG, no artificial colors or flavors. That doesn’t mean every item is organic. Some are made with organic ingredients but are not Certified Organic. Some go far beyond organic. They all are earth-friendly, non-GMO and meticulously chosen for their healthful qualities. Azure’s Unacceptable Ingredient List for Food Items: Artificial Colors Certified Colors Pork Products Artificial Flavors Fluoride Shellfish Products (except Artificial Nitrates/Nitrites in Genetically Modified when used as an ingredient Meat Products Organisms (GMOs) in nutritional supplements) Artificial Preservatives Monosodium Glutamate Alcohol Artificial Sweeteners (MSG) Tobacco Bleached Flour Refined Conventional Sugars A Word about “Natural” Flavorings: Azure is currently reviewing all products that include “natural flavorings” for items that are unacceptable. All new vendors are required to sign a certification letter clearly stating -

Vegan Protein Blend Ve Gan Pro Tein Blend

VEGAN PROTEIN BLEND FDA cGMP Guaranteed, Distributed by: Our unique 100% plant-based MCT Foods, LLC 630 Vernon Ave. blend is a delicious, non-GMO, Glencoe, IL 60022 high-fiber functional food that 847-835-0500 fax: 847-835-1190 is free of gluten, dairy, lactose, [email protected] soy, and corn. Orders may be placed at www.mctLean.com Discussion Clinical Applications Vegan Protein Blend is MCT Lean’s proprietary blend of • Contains 20g of protein pea protein isolate and rice protein concentrate, L-glutamine, • Contains MCTs that aid in weight loss & glycine, taurine, and SGS™ broccoli seed extract. This muscle maintenance broccoli seed extract is a super-vegetable boasting the highest level of glucoraphanin - enhancing cell detoxification • Only 6 grams net carbs per serving through free radical elimination. Our blend also contains (Cocoa flavor. Vanilla has 7g) Aminogen®, a patented, natural, plant-derived enzyme system • Supports the following: clinically proven to increase protein digestion and amino Lean body composition acid absorption - boosting nitrogen retention, aiding in the Immune health synthesis of muscle mass, and promoting deep muscle recovery. Cardiovascular health Healthy blood insulin/glucose levels Pea protein isolate features a well-balanced amino acid Gastrointestinal health BLEND PROTEIN VEGAN profile, including the highest lysine, arginine, and branched- chain amino acid (BCAA) content of all commercially available plant-based protein sources. Lysine speeds up muscle recovery time, while also playing a key role in muscle building and nitrogen level preservation. Arginine increases blood flow to allow muscles to receive nutrients and oxygen faster, thus promoting fat loss, encouraging lean muscle growth and development, and improving muscle recovery. -

TOTAL FOLATE in PEANUTS and PEANUT PRODUCTS by LAKSHMI

TOTAL FOLATE IN PEANUTS AND PEANUT PRODUCTS by LAKSHMI KOTA (Under the Direction of Ronald R. Eitenmiller) ABSTRACT Samples consisting of 222 cultivar specific samples of four different peanut types (Runner, Virginia, Spanish and Valencia) from 2 years (2005 and 2006) from 3 geographical locations (Southeast, Southwest and Virginia/Carolina) were collected for the study. No significant differences were noted among the folate levels by types for 2005 crop year peanuts (P>0.05). For 2006 peanuts, Spanish peanuts were statistically lower in folate than Runner and Virginia peanuts (P<0.05). For the Runner cultivars, significant (P<0.05) differences existed among cultivars with some significant year-to-year variation. Year of harvest did not have significant effect on folate content of Virginia peanuts. Folate contents among Virginia cultivars were statistically similar in 2005 and 2006. For Spanish cultivars in 2005, OLin had significantly higher folate than Tamspan 90. Overall means for both Runner and Spanish peanut types showed that high-oleic cultivars contained significantly higher total folate levels than normal cultivars (P<0.05). Folate levels in peanuts from Virginia/Carolina region varied significantly by production year, but peanuts from Southeast and Southwest region did not vary from 2005 to 2006. Response surface methodology (RSM) was used to optimize the trienzyme digestion for the extraction of total folate from peanut butter. The predicted second-order polynomial model was adequate (R 2 = 0.97) with a small coefficient of variation (3.05). Both Pronase R and conjugase had significant effects on the extraction. Ridge analysis gave an optimum trienzyme time: Pronase R, 1h; α-amylase, 1.5 h; conjugase, 1h. -

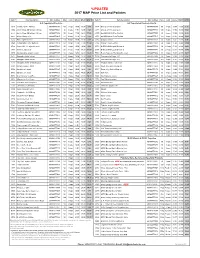

*UPDATED 2017 MAP Price List and Policies

*UPDATED 2017 MAP Price List and Policies Item # Item Description UPC number Size Form Whsle MSRP MAP $ Item # Item Description UPC number Size Form whsle MSRP MAP $ A-Z Capsulated Products A-Z Capsulated Products Cont'd. A715 Acai Energy 4:1 400 mg 601944777159 60 Vcaps 10.00 19.99 9.99 O734 Olive Leaf 18% Oleuropein 601944777340 60 Vcaps 10.00 19.99 9.99 A704 Activin Grape SE w/Amla 125 mg 601944777043 30 Vcaps 7.50 14.99 7.49 O773 Olive Leaf 18% Oleuropein 601944777739 120 Vcaps 17.50 34.99 17.49 A723 Activin Grape SE w/Amla 125 mg 601944777234 90 Vcaps 17.50 34.99 17.49 O750 OptiMSM 99.9% Pure Distilled 601944777500 90 Vcaps 10.00 19.99 9.99 A841 African Mango 10:1 601944778415 60 Vcaps 10.00 19.99 9.99 O751 OptiMSM 99.9% Pure Distilled 601944777517 180 Vcaps 20.00 39.99 19.99 A745 Amla, organic extract 601944777456 60 Vcaps 10.00 19.99 9.99 O765 Oregano extract 601944777654 60 Vcaps 8.50 16.99 8.49 A747 Andrographis, with Elderberry 601944777470 60 Vcaps 12.50 24.99 12.49 P766 Passion Flower extract 601944777661 60 Vcaps 15.00 29.99 14.99 A788 Arjuna 10:1, 1% arjunolic acids 601944777883 60 Vcaps 10.00 19.99 9.99 Q753 QVEG CoQ10 Liquid Enhanced 601944777531 30 LVcaps 17.96 29.99 14.99 A733 Artichoke, European 601944777333 60 Vcaps 17.50 34.99 17.49 Q754 QVEG CoQ10 Liquid Enhanced 601944777548 60 LVcaps 32.93 54.99 27.49 A735 Ashwagandha, organic extract 601944777357 60 Vcaps 12.50 24.99 12.49 R743 Reishi, Supreme Red Ling Zhi extract 601944777432 60 Vcaps 15.00 29.99 14.99 A727 Astragalus herbal extract 601944777272 60 Vcaps 10.00 -

GRAS Notice 851, Pea Protein

GRAS Notice (GRN) No. 851 https://www.fda.gov/food/generally-recognized-safe-gras/gras-notice-inventory 1001 G Street, N.W. Suite 500 West Washington, D.C. 20001 tel. 202.434.4100 fax 202.434.4646 Writer's Direct Access Evangelia C. Pelonis (202) 434-4 l06 pe I on i s@k h I aw. com January 28, 2019 Via FedEx & CD-ROM . Dr. Susan Carlson Director, Division of Biotechnology and GRAS Notice Review Office of Food Additive Safety (HFS-200) Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition Food and Drug Administration 5100 Paint Branch Parkway College Park, MD 20740-3835 Re: GRAS Notification for Roquette Freres Pea Protein Isolate Dear Dr. Carlson: We respectfully submit the attached GRAS Notification on behalf of our client, Roquette Freres (Roquette) for pea protein isolate to be used as a concentrated, highly digestible protein source in various food categories (excluding infant formula) and as a binder and extender in meat and poultry products. The pea protein isolate will be used as a substitute for, and/or in conjunction with, other proteins in conventional food products, as well as in meal replacement and dry blend protein powder applications. Thus, the pea protein isolate will not contribute any additional exposure to protein and it is not intended to be used to replace the entire daily protein intake or as the sole source of protein in the diet for consumers. More detailed information regarding product identification, intended use levels, and the manufacturing and safety of the ingredient is set forth in the attached GRAS Notification. -

Premier Plant Protein

PREMIER Six Premier Types of Plant-Based Protein PLANT PROTEIN An Excellent Source of Digestible Protein with 60+ Minerals Pea Rice Hemp Seed Pumpkin Seed Quinoa Pomegranate ARE YOU GETTING ENOUGH QUALITY PROTEIN IN YOUR DIET? ✔ 18 G of plant protein ✔ 100% organic ingredients ✔ Pure vegan ✔ 60+ trace minerals ✔ Pesticide screened ✔ Dairy free ✔ No artificial flavors ✔ NO synthetic ingredients ✔ Heavy metal examined These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. These products are not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease. Commitment to Excellence: the world leader in cellular resonant formulations Each PRL Formula Meets or 3500-B Wadley Place, Austin, TX 78728 Exceeds FDA/cGMP Standards 800-325-7734 ● fax 512-341-3931 Ĥ Dairy Free Ĥ Mycotoxin screened Ĥ Pesticide screened Ĥ Phyto-forensic tested for adulterants EASY TO USE Simply add Quantum Plant Protein to food or drinks to increase quality protein content. It mixes well with liquid and makes an excellent foundation for a good-tasting, protein-rich smoothie. Premier Plant Protein is suitable for most anyone, including those on vegetarian or vegan diets, or those who want to avoid dairy protein sources or who have sensitivities to milk or whey protein. ✔ WHERE Anywhere … add to drinks at home, in the office, at the gym, on the beach, at the pool... all places are suitable “to enjoy” this great-tasting, healthy protein powder. ✔ HOW Premier Plant Protein liberates the nutritive power of high Simply add a scoop to a glass of water or other liquids and stir. quality, living seeds, grains and legumes (pea) as a high Mixes well with foods and smoothies. -

Effects of Whey and Pea Protein Supplementation on Post-Eccentric

nutrients Article Effects of Whey and Pea Protein Supplementation on Post-Eccentric Exercise Muscle Damage: A Randomized Trial David C. Nieman 1,* , Kevin A. Zwetsloot 2, Andrew J. Simonson 1, Andrew T. Hoyle 1, Xintang Wang 3, Heather K. Nelson 4, Catherine Lefranc-Millot 5 and Laetitia Guérin-Deremaux 5 1 Human Performance Laboratory, Department of Biology, Appalachian State University, North Carolina Research Campus, Kannapolis, NC 28608, USA; [email protected] (A.J.S.); [email protected] (A.T.H.) 2 Department of Health and Exercise Science, Appalachian State University, Boone, NC 28608, USA; [email protected] 3 China Academy of Sport and Health Sciences, Beijing Sport University, Beijing 100084, China; [email protected] 4 Nutrition and Health Research & Development, Roquette, Geneva, IL 60134, USA; [email protected] 5 Nutrition and Health Research & Development, Roquette, 62136 Lestrem, France; [email protected] (C.L.-M.); [email protected] (L.G.-D.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-(828)-773-0056 Received: 14 July 2020; Accepted: 7 August 2020; Published: 9 August 2020 Abstract: This randomized trial compared pea protein, whey protein, and water-only supplementation on muscle damage, inflammation, delayed onset of muscle soreness (DOMS), and physical fitness test performance during a 5-day period after a 90-min eccentric exercise bout in non-athletic non-obese males (n = 92, ages 18–55 years). The two protein sources (0.9 g protein/kg divided into three doses/day) were administered under double blind procedures. The eccentric exercise protocol induced significant muscle damage and soreness, and reduced bench press and 30-s Wingate performance. -

Alternative Proteins: the Race for Market Share Is on Consumer Interest in Non-Meat-Based Protein Options Is Increasing Globally

Agriculture Practice Alternative proteins: The race for market share is on Consumer interest in non-meat-based protein options is increasing globally. Food industry players that want to capture the opportunity must understand the evolving market dynamics and where to place their bets. by Zafer Bashi, Ryan McCullough, Liane Ong, and Miguel Ramirez © baibaz/Getty Images August 2019 In countries with economic wealth, there is capabilities to capture this market opportunity, nor growing consumer awareness of, and interest do they know where to focus their efforts. in, alternative proteins. Meat has been the main source of protein in developed markets for years, In response to these market forces and consumer and there has been an increased appetite for concerns, industry leaders are rolling out a range traditional protein in developing markets in recent of products and ingredients using different plant- years. However, changing consumer behavior and based proteins (soy, pea), new animal sources interest in alternative-protein sources—due in part (insects), and biotechnological innovations (cultured to health and environmental concerns as well as meat or fungal protein). In fact, a 2015 McKinsey animal welfare—have made way for growth in the survey of dairy-industry professionals showed that alternative-proteins market. 21 percent of respondents believe the nondairy alternatives market, including plant protein, is Several entrants in the alternative-protein space are “sizable and will continue to grow.”6 already rolling out new technologies and ingredients, and some are attempting to solidify their place in For CPG companies and food manufacturers to win the market. Innovative food companies are able to market share in this fast-growing segment over mirror the customer experience of eating meat to a the long term, they must invest in the capabilities much higher degree. -

Composition, Physicochemical Properties of Pea Protein and Its Application in Functional Foods

Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition ISSN: 1040-8398 (Print) 1549-7852 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/bfsn20 Composition, physicochemical properties of pea protein and its application in functional foods Z. X. Lu, J. F. He, Y. C. Zhang & D. J. Bing To cite this article: Z. X. Lu, J. F. He, Y. C. Zhang & D. J. Bing (2019): Composition, physicochemical properties of pea protein and its application in functional foods, Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, DOI: 10.1080/10408398.2019.1651248 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2019.1651248 Published online: 20 Aug 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 286 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=bfsn20 CRITICAL REVIEWS IN FOOD SCIENCE AND NUTRITION https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2019.1651248 REVIEW Composition, physicochemical properties of pea protein and its application in functional foods Z. X. Lua,J.F.Heb, Y. C. Zhanga, and D. J. Bingc aLethbridge Research and Development Centre, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada; bInner Mongolia Academy of Agriculture and Animal Husbandry Sciences, Hohhot, Inner Mongolia, P.R. China; cLacombe Research and Development Centre, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Lacombe, Alberta, Canada ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Field pea is one of the most important leguminous crops over the world. Pea protein is a rela- Pea; protein; composition; tively new type of plant proteins and has been used as a functional ingredient in global food physicochemical property; industry. -

Peas, Lentils, Chickpeas... Pulses: Edible Dry Seeds from Pulse Plants ~ Pulsemeal: Roasted Yellow Pea Flour

Baking Guide: Enhance the Nutritional Profile of Baked Goods with Pulses as Ingredients USA Dry Pea & Lentil Council Peas, Lentils, Chickpeas... Pulses: edible dry seeds from pulse plants ~ Pulsemeal: roasted yellow pea flour Nutritionally powerful. Dry peas are functional food market expected to grow from ing with natural fiber from whole foods is no among the most powerful of pulses. Their nu- $25 billion to almost $40 billion by 2011. fad. Both the American Heart Association and tritional importance dates back almost 10,000 the American Dietetic Association continue to years BC when the protein and energy in these Practical and naturally wholesome. emphasize the vital role that natural sources of legume seeds were essential to developing civi- Within the last two years, 65% of consumers dietary fiber play in maintaining good health. lizations. Even in these modern times the high report a greater interest in healthy eating, ac- quality protein, natural dietary fiber and ben- cording to market research from Tate and Lyle. Good ‘carbs’ are slow ‘carbs’. Closely eficial starch in dry peas is difficult to match. The nutritional components in pulses such as behind the clamor for fiber, listen for the buzz Today, pea derivatives such as roasted pea flour pea flour can contribute to food product for- about the benefits of low “GI” foods. Pulses (peasemeal), pea flour protein concentrates, mulations that address these growing concerns such as dry peas have a low glycemic index pea fiber and starch isolates have emerged as about digestive and cardiovascular health as (GI), meaning a complex, slowly-digesting functional food ingredients that deliver fresh well as weight control and diabetes. -

Supplement Facts Supplement Facts Serving Size: One Scoop (37.57 G) Serving Size: One Scoop (30.17 G) Amino Acid Balance of Human Muscle

PureGreen Protein • Chocolate PureGreen Protein • Mixed Berry The ONLY protein supplement with the Supplement Facts Supplement Facts Serving Size: one scoop (37.57 g) Serving Size: one scoop (30.17 g) amino acid balance of human muscle. Servings per container: 13 or 10 Servings per container: 15 or 10 Why even consider anything else? Amount per serving Amount per serving Calories: 129 Calories from fat: 14.4 Calories: 109 Calories from fat: 14.4 PureGreen Protein: The Smart Alternative · Balanced Amino Acids Amount %Daily Value Amount %Daily Value Total Fat 1.6 g 2.5% Total Fat 1.6 g 2.5% to Match Human Most of today’s meat and dairy products carry dangerous Saturated 0.42 g 2.1% Saturated 0.42 g 2.1% Muscle Tissue amounts of growth stimulant, antibiotic, and hormone Polyunsaturated 0.82 g 17.3% Polyunsaturated 0.82 g 17.3% contaminants. Plant proteins are free of those harmful Monounsaturated 0.29 g 6.1% Monounsaturated 0.29 g 6.1% substances. They can be used in place of animal protein, Cholesterol 0 g 0.0% Cholesterol 0 g 0.0% · 20g of Protein per but only if all the essential amino acids are present in the Sodium 195 mg 8.13% Sodium 195 mg 8.13% serving Potassium 104 mg 2.97% Potassium 104 mg 2.97% right combination. Total Carbohydrate 9 g 2.12% Total Carbohydrate 4 g 2.12% Dietary fiber 1.36 g 5.4% Dietary fiber 1.36 g 5.4% · As much protein per Most plant proteins lack one or more essential amino acids, Sugars 5.09 g Sugars 0.09 g serving as in 27servings Protein 20 g Protein 20 g or contain so little of one that it is as if the amino acid were of vegetables Vitamin A (from beta carotene) 0 i.u.