Cost-Effectiveness of Rate- and Rhythm-Control Drugs for Treating Atrial Fibrillation in Korea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Product List March 2019 - Page 1 of 53

Wessex has been sourcing and supplying active substances to medicine manufacturers since its incorporation in 1994. We supply from known, trusted partners working to full cGMP and with full regulatory support. Please contact us for details of the following products. Product CAS No. ( R)-2-Methyl-CBS-oxazaborolidine 112022-83-0 (-) (1R) Menthyl Chloroformate 14602-86-9 (+)-Sotalol Hydrochloride 959-24-0 (2R)-2-[(4-Ethyl-2, 3-dioxopiperazinyl) carbonylamino]-2-phenylacetic 63422-71-9 acid (2R)-2-[(4-Ethyl-2-3-dioxopiperazinyl) carbonylamino]-2-(4- 62893-24-7 hydroxyphenyl) acetic acid (r)-(+)-α-Lipoic Acid 1200-22-2 (S)-1-(2-Chloroacetyl) pyrrolidine-2-carbonitrile 207557-35-5 1,1'-Carbonyl diimidazole 530-62-1 1,3-Cyclohexanedione 504-02-9 1-[2-amino-1-(4-methoxyphenyl) ethyl] cyclohexanol acetate 839705-03-2 1-[2-Amino-1-(4-methoxyphenyl) ethyl] cyclohexanol Hydrochloride 130198-05-9 1-[Cyano-(4-methoxyphenyl) methyl] cyclohexanol 93413-76-4 1-Chloroethyl-4-nitrophenyl carbonate 101623-69-2 2-(2-Aminothiazol-4-yl) acetic acid Hydrochloride 66659-20-9 2-(4-Nitrophenyl)ethanamine Hydrochloride 29968-78-3 2,4 Dichlorobenzyl Alcohol (2,4 DCBA) 1777-82-8 2,6-Dichlorophenol 87-65-0 2.6 Diamino Pyridine 136-40-3 2-Aminoheptane Sulfate 6411-75-2 2-Ethylhexanoyl Chloride 760-67-8 2-Ethylhexyl Chloroformate 24468-13-1 2-Isopropyl-4-(N-methylaminomethyl) thiazole Hydrochloride 908591-25-3 4,4,4-Trifluoro-1-(4-methylphenyl)-1,3-butane dione 720-94-5 4,5,6,7-Tetrahydrothieno[3,2,c] pyridine Hydrochloride 28783-41-7 4-Chloro-N-methyl-piperidine 5570-77-4 -

Properties and Units in Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology

Pure Appl. Chem., Vol. 72, No. 3, pp. 479–552, 2000. © 2000 IUPAC INTERNATIONAL FEDERATION OF CLINICAL CHEMISTRY AND LABORATORY MEDICINE SCIENTIFIC DIVISION COMMITTEE ON NOMENCLATURE, PROPERTIES, AND UNITS (C-NPU)# and INTERNATIONAL UNION OF PURE AND APPLIED CHEMISTRY CHEMISTRY AND HUMAN HEALTH DIVISION CLINICAL CHEMISTRY SECTION COMMISSION ON NOMENCLATURE, PROPERTIES, AND UNITS (C-NPU)§ PROPERTIES AND UNITS IN THE CLINICAL LABORATORY SCIENCES PART XII. PROPERTIES AND UNITS IN CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY AND TOXICOLOGY (Technical Report) (IFCC–IUPAC 1999) Prepared for publication by HENRIK OLESEN1, DAVID COWAN2, RAFAEL DE LA TORRE3 , IVAN BRUUNSHUUS1, MORTEN ROHDE1, and DESMOND KENNY4 1Office of Laboratory Informatics, Copenhagen University Hospital (Rigshospitalet), Copenhagen, Denmark; 2Drug Control Centre, London University, King’s College, London, UK; 3IMIM, Dr. Aiguader 80, Barcelona, Spain; 4Dept. of Clinical Biochemistry, Our Lady’s Hospital for Sick Children, Crumlin, Dublin 12, Ireland #§The combined Memberships of the Committee and the Commission (C-NPU) during the preparation of this report (1994–1996) were as follows: Chairman: H. Olesen (Denmark, 1989–1995); D. Kenny (Ireland, 1996); Members: X. Fuentes-Arderiu (Spain, 1991–1997); J. G. Hill (Canada, 1987–1997); D. Kenny (Ireland, 1994–1997); H. Olesen (Denmark, 1985–1995); P. L. Storring (UK, 1989–1995); P. Soares de Araujo (Brazil, 1994–1997); R. Dybkær (Denmark, 1996–1997); C. McDonald (USA, 1996–1997). Please forward comments to: H. Olesen, Office of Laboratory Informatics 76-6-1, Copenhagen University Hospital (Rigshospitalet), 9 Blegdamsvej, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark. E-mail: [email protected] Republication or reproduction of this report or its storage and/or dissemination by electronic means is permitted without the need for formal IUPAC permission on condition that an acknowledgment, with full reference to the source, along with use of the copyright symbol ©, the name IUPAC, and the year of publication, are prominently visible. -

Uniqueness of Pilsicainide in Class Ic Antiarrhythmics Takeshi

Uniqueness of Pilsicainide in Class Ic Antiarrhythmics Takeshi YAMASHITA, MD, Yuji MURAKAWA, MD, Kazunori SEZAKI, MD, Noriyuki HAYAMI, MD, Masashi INOUE, MD, Ei-ichi FUKUI, MD, and Masao OMATA, MD SUMMARY Pilsicainide, a class Ic agent, is known to be an effective drug particularly for treating atrial tachyarrhythmias. However, its electrophysiological effects on the atrium have not been well studied. To characterize the electrophysiologic effects of pilsicainide on atrial myocytes in class Ic drugs, we examined the effects of this drug on membrane currents in single rabbit atrial myocytes using the tight-seal whole cell voltage-clamp technique. Under the current-clamp condition, pilsicainide did not affect the action potential duration at therapeutic ranges (3ƒÊM) and slightly shortened it at higher concentrations (10ƒÊM). These observations were quite different from those with other class Ic agents including flecainide and propafenone which prolong the atrial action potential duration. The drug did not affect the resting membrane potential. Under the voltage-clamp condition, pilsicainide inhibited the transient outward current (Ito) that is more prominent in the atrium than in the ventricle in a concentra- tion-dependent manner. However, in contrast to other class Ic agents, the inhibition of Ito by pilsicainide was observed only at much higher concentra- tions (IC50-300ƒÊM) and did not affect the inactivation time-course of Ito. Moreover, the drug (10ƒÊM) did not significantly affect the Ca2+, delayed rec- tifier K+, inward rectifying K+, acetylcholine-induced K+ or ATP-sensitive K+ currents. From these results, pilsicainide could be differentiated as a pure Na+ channel blocker from other class Ic agents with diverse effects on membrane currents and should be recognized accordingly in clinical situations. -

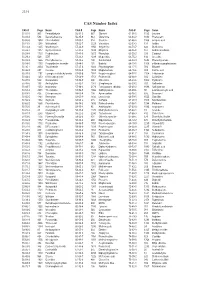

CAS Number Index

2334 CAS Number Index CAS # Page Name CAS # Page Name CAS # Page Name 50-00-0 905 Formaldehyde 56-81-5 967 Glycerol 61-90-5 1135 Leucine 50-02-2 596 Dexamethasone 56-85-9 963 Glutamine 62-44-2 1640 Phenacetin 50-06-6 1654 Phenobarbital 57-00-1 514 Creatine 62-46-4 1166 α-Lipoic acid 50-11-3 1288 Metharbital 57-22-7 2229 Vincristine 62-53-3 131 Aniline 50-12-4 1245 Mephenytoin 57-24-9 1950 Strychnine 62-73-7 626 Dichlorvos 50-23-7 1017 Hydrocortisone 57-27-2 1428 Morphine 63-05-8 127 Androstenedione 50-24-8 1739 Prednisolone 57-41-0 1672 Phenytoin 63-25-2 335 Carbaryl 50-29-3 569 DDT 57-42-1 1239 Meperidine 63-75-2 142 Arecoline 50-33-9 1666 Phenylbutazone 57-43-2 108 Amobarbital 64-04-0 1648 Phenethylamine 50-34-0 1770 Propantheline bromide 57-44-3 191 Barbital 64-13-1 1308 p-Methoxyamphetamine 50-35-1 2054 Thalidomide 57-47-6 1683 Physostigmine 64-17-5 784 Ethanol 50-36-2 497 Cocaine 57-53-4 1249 Meprobamate 64-18-6 909 Formic acid 50-37-3 1197 Lysergic acid diethylamide 57-55-6 1782 Propylene glycol 64-77-7 2104 Tolbutamide 50-44-2 1253 6-Mercaptopurine 57-66-9 1751 Probenecid 64-86-8 506 Colchicine 50-47-5 589 Desipramine 57-74-9 398 Chlordane 65-23-6 1802 Pyridoxine 50-48-6 103 Amitriptyline 57-92-1 1947 Streptomycin 65-29-2 931 Gallamine 50-49-7 1053 Imipramine 57-94-3 2179 Tubocurarine chloride 65-45-2 1888 Salicylamide 50-52-2 2071 Thioridazine 57-96-5 1966 Sulfinpyrazone 65-49-6 98 p-Aminosalicylic acid 50-53-3 426 Chlorpromazine 58-00-4 138 Apomorphine 66-76-2 632 Dicumarol 50-55-5 1841 Reserpine 58-05-9 1136 Leucovorin 66-79-5 -

Pharmacodynamic Evaluation of Β-Blockade Associated with Atenolol

Pharmacodynamic HYDOXDWLRQRIȕ-blockade associated with atenolol in healthy dogs Mari Waterman Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science In Biomedical and Veterinary Sciences Jonathan A. Abbott, Chair Andrea C. Eriksson Jeffrey R. Wilcke July 30, 2018 Blacksburg, VA .H\ZRUGVDWHQROROȕ-blockade, isoproterenol, dog, pharmacodynamic Copyright 2018 Mari Waterman Pharmacodynamic HYDOXDWLRQRIȕ-blockade associated with atenolol in healthy dogs Mari Waterman ABSTRACT Objective: Dosing intervals of 12 and 24 hours for atenolol have been recommended, but an evidentiary basis is lacking. To test the hypothesis that repeated, once-daily oral administration of atenolol attenuates the heart rate response to isoproterenol for 24 hours, we performed a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled cross-over experiment. Animals: Twenty healthy dogs Procedures: Dogs were randomly assigned to receive either placebo (P) and then atenolol (A), [1 mg/kg PO q24h] or vice versa. Treatment periods were 5-7 days; time between periods was 7 days. Heart rates (bpm) at rest (HRr DQG GXULQJ FRQVWDQW UDWH > ȝJNJPLQ@ LQIXVLRQ RI isoproterenol (HRi) were electrocardiographically obtained 0, 0.25, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 hours after final administration of drug or placebo. A mixed model ANOVA was used to evaluate the effects of treatment (Tr), time after drug or placebo administration (t), interaction of treatment and time (Tr*t) as well as period and sequence on HRr and HRi. Results: Sequence or period effects were not detected. There was a significant effect of Tr (p <0.0001) and Tr*t (p <0.0001) on HRi. -

What Is the Diagnosis?

CLINICAL ARRHYTHMIA https://doi.org/10.24207/jca.v32i2.988_IN Challenge What is the Diagnosis? CASE PRESENTATION A female 82-year-old Caucasian patient with a history of paroxysmal atrial fi brillation (AF) for several years, with palpitation crises of varying duration between a few minutes and several hours, without clinical control, using beta-blockers and diltiazem. Th e patient presented complaints of fatigue on moderate eff orts, without precordial pain or syncope, with progressive asthenia and indisposition. She informed three previous hospitalizations for chemical cardioversion of AF. Th e patient had a history of systemic arterial hypertension, hypothyroidism, and atherosclerotic heart disease, and underwent coronary angioplasty in 2014 with the placement of a nonpharmacological stent, without a prior heart attack. She was on regular use of irbesartan 300 mg, clopidogrel 75 mg, and levothyroxine 75 mcg. Over the past eight months, there has been a worsening of AF crises, and she started to take propafenone in increasing doses, initially 150 mg BID, without improvement of symptoms, then 300 mg BID and currently 750 mg/day (300 – 150 – 300 mg 8/8 hours), without control of palpitations and with feeling of discomfort and weakness. On physical examination, the patient was in good general condition, with no signifi cant abnormalities. Her blood pressure was at 135/80 mmHg, with a heart rate of 72 bpm, irregular rhythm due to the presence of extrasystoles, normophonetic sounds in two times and mild systolic murmur at a mitral focus. Laboratory tests were within normal limits. Th e patient presented Doppler echocardiography with left ventricle (LV) with standard segmental dimensions and contractility, ejection fraction of 68%, slight concentric LV hypertrophy, left atrium with slight increase (44 mm), alteration in LV distensibility, presence of mild mitral valve insuffi ciency and absence of pulmonary arterial hypertension or dilatation of right chambers. -

![Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8870/ehealth-dsi-ehdsi-v2-2-2-or-ehealth-dsi-master-value-set-1028870.webp)

Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set

MTC eHealth DSI [eHDSI v2.2.2-OR] eHealth DSI – Master Value Set Catalogue Responsible : eHDSI Solution Provider PublishDate : Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 1 of 490 MTC Table of Contents epSOSActiveIngredient 4 epSOSAdministrativeGender 148 epSOSAdverseEventType 149 epSOSAllergenNoDrugs 150 epSOSBloodGroup 155 epSOSBloodPressure 156 epSOSCodeNoMedication 157 epSOSCodeProb 158 epSOSConfidentiality 159 epSOSCountry 160 epSOSDisplayLabel 167 epSOSDocumentCode 170 epSOSDoseForm 171 epSOSHealthcareProfessionalRoles 184 epSOSIllnessesandDisorders 186 epSOSLanguage 448 epSOSMedicalDevices 458 epSOSNullFavor 461 epSOSPackage 462 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 2 of 490 MTC epSOSPersonalRelationship 464 epSOSPregnancyInformation 466 epSOSProcedures 467 epSOSReactionAllergy 470 epSOSResolutionOutcome 472 epSOSRoleClass 473 epSOSRouteofAdministration 474 epSOSSections 477 epSOSSeverity 478 epSOSSocialHistory 479 epSOSStatusCode 480 epSOSSubstitutionCode 481 epSOSTelecomAddress 482 epSOSTimingEvent 483 epSOSUnits 484 epSOSUnknownInformation 487 epSOSVaccine 488 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 3 of 490 MTC epSOSActiveIngredient epSOSActiveIngredient Value Set ID 1.3.6.1.4.1.12559.11.10.1.3.1.42.24 TRANSLATIONS Code System ID Code System Version Concept Code Description (FSN) 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 -

Ventricular Tachycardia Drugs Versus Devices John Camm St

Cardiology Update 2015 Davos, Switzerland: 8-12th February 2015 Ventricular Arrhythmias Ventricular Tachycardia Drugs versus Devices John Camm St. George’s University of London, UK Imperial College, London, UK Declaration of Interests Chairman: NICE Guidelines on AF, 2006; ESC Guidelines on Atrial Fibrillation, 2010 and Update, 2012; ACC/AHA/ESC Guidelines on VAs and SCD; 2006; NICE Guidelines on ACS and NSTEMI, 2012; NICE Guidelines on heart failure, 2008; NICE Guidelines on Atrial Fibrillation, 2006; ESC VA and SCD Guidelines, 2015 Steering Committees: multiple trials including novel anticoagulants DSMBs: multiple trials including BEAUTIFUL, SHIFT, SIGNIFY, AVERROES, CASTLE- AF, STAR-AF II, INOVATE, and others Events Committees: one trial of novel oral anticoagulants and multiple trials of miscellaneous agents with CV adverse effects Editorial Role: Editor-in-Chief, EP-Europace and Clinical Cardiology; Editor, European Textbook of Cardiology, European Heart Journal, Electrophysiology of the Heart, and Evidence Based Cardiology Consultant/Advisor/Speaker: Astellas, Astra Zeneca, ChanRX, Gilead, Merck, Menarini, Otsuka, Sanofi, Servier, Xention, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol- Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Pfizer, Boston Scientific, Biotronik, Medtronic, St. Jude Medical, Actelion, GlaxoSmithKline, InfoBionic, Incarda, Johnson and Johnson, Mitsubishi, Novartis, Takeda Therapy for Ventricular Tachycardia Medical therapy Antiarrhythmic drugs Autonomic management Ventricular tachycardia Monomorphic Polymorphic Ventricular fibrillation Ventricular storms Ablation therapy Device therapy Surgical Defibrillation Catheter Antitachycardia pacing History of Antiarrhythmic Drugs 1914 - Quinidine 1950 - Lidocaine 1951 - Procainamide 1946 – Digitalis 1956 – Ajmaline 1962 - Verapamil 1962 – Disopyramide 1964 - Propranolol 1967 – Amiodarone 1965 – Bretylium 1972 – Mexiletine 1973 – Aprindine, Tocainide 1969 - Diltiazem 1975- Flecainide 1976 – Propafenone Encainide Ethmozine 2000 - Sotalol D-sotalol 1995 - Ibutilide (US) Recainam 2000 – Dofetilide US) IndecainideX Etc. -

Jp Xvii the Japanese Pharmacopoeia

JP XVII THE JAPANESE PHARMACOPOEIA SEVENTEENTH EDITION Official from April 1, 2016 English Version THE MINISTRY OF HEALTH, LABOUR AND WELFARE Notice: This English Version of the Japanese Pharmacopoeia is published for the convenience of users unfamiliar with the Japanese language. When and if any discrepancy arises between the Japanese original and its English translation, the former is authentic. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Ministerial Notification No. 64 Pursuant to Paragraph 1, Article 41 of the Law on Securing Quality, Efficacy and Safety of Products including Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices (Law No. 145, 1960), the Japanese Pharmacopoeia (Ministerial Notification No. 65, 2011), which has been established as follows*, shall be applied on April 1, 2016. However, in the case of drugs which are listed in the Pharmacopoeia (hereinafter referred to as ``previ- ous Pharmacopoeia'') [limited to those listed in the Japanese Pharmacopoeia whose standards are changed in accordance with this notification (hereinafter referred to as ``new Pharmacopoeia'')] and have been approved as of April 1, 2016 as prescribed under Paragraph 1, Article 14 of the same law [including drugs the Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare specifies (the Ministry of Health and Welfare Ministerial Notification No. 104, 1994) as of March 31, 2016 as those exempted from marketing approval pursuant to Paragraph 1, Article 14 of the Same Law (hereinafter referred to as ``drugs exempted from approval'')], the Name and Standards established in the previous Pharmacopoeia (limited to part of the Name and Standards for the drugs concerned) may be accepted to conform to the Name and Standards established in the new Pharmacopoeia before and on September 30, 2017. -

Translational Studies on Anti-Atrial Fibrillatory Action of Oseltamivir by Its in Vivo and in Vitro Electropharmacological Analyses

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 29 April 2021 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.593021 Translational Studies on Anti-Atrial Fibrillatory Action of Oseltamivir by its in vivo and in vitro Electropharmacological Analyses Ryuichi Kambayashi 1, Hiroko Izumi-Nakaseko 1, Ai Goto 1, Kazuya Tsurudome 2, Hironori Ohshiro 2, Taku Izumi 2, Mihoko Hagiwara-Nagasawa 1, Koki Chiba 1, Ryota Nishiyama 3, Satomi Oyama 3, Yoshio Nunoi 1, Yoshinori Takei 4, Akio Matsumoto 5 and Atsushi Sugiyama 1,4,5,6* 1Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Toho University, Tokyo, Japan, 2Sophion Bioscience K.K., Saitama, Japan, 3Drug Research Department, TOA EIYO LTD., Fukushima, Japan, 4Department of Translational Research and Cellular Therapeutics, Faculty of Medicine, Toho University, Tokyo, Japan, 5Department of Aging Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Toho University, Tokyo, Japan, 6Yamanashi Research Center of Clinical Pharmacology, Yamanashi, Japan Edited by: Oseltamivir has been shown to prolong the atrial conduction time and effective refractory Apostolos Zarros, University of Glasgow, period, and to suppress the onset of burst pacing-induced atrial fibrillation in vitro.Tobetter United Kingdom predict its potential clinical benefit as an anti-atrial fibrillatory drug, we performed translational Reviewed by: studies by assessing in vivo anti-atrial fibrillatory effect along with in vivo and in vitro Ilya Kolb, Janelia Research Campus, electropharmacological analyses. Oseltamivir in intravenous doses of 3 (n 6) and United States 30 mg/kg (n 7) was administered in conscious state to the persistent atrial fibrillation Jordi Heijman, model dogs to confirm its anti-atrial fibrillatory action. The model was prepared by tachypacing Maastricht University, Netherlands > *Correspondence: to the atria of chronic atrioventricular block dogs for 6 weeks. -

Pharmaceutical Appendix to the Tariff Schedule 2

Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2007) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2007) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 2 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. ABACAVIR 136470-78-5 ACIDUM LIDADRONICUM 63132-38-7 ABAFUNGIN 129639-79-8 ACIDUM SALCAPROZICUM 183990-46-7 ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACIDUM SALCLOBUZICUM 387825-03-8 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ACIFRAN 72420-38-3 ABAPERIDONUM 183849-43-6 ACIPIMOX 51037-30-0 ABARELIX 183552-38-7 ACITAZANOLAST 114607-46-4 ABATACEPTUM 332348-12-6 ACITEMATE 101197-99-3 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ACITRETIN 55079-83-9 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ACIVICIN 42228-92-2 ABETIMUSUM 167362-48-3 ACLANTATE 39633-62-0 ABIRATERONE 154229-19-3 ACLARUBICIN 57576-44-0 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ACLATONIUM NAPADISILATE 55077-30-0 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ACODAZOLE 79152-85-5 ABRINEURINUM 178535-93-8 ACOLBIFENUM 182167-02-8 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ACONIAZIDE 13410-86-1 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ACOTIAMIDUM 185106-16-5 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2015/0202317 A1 Rau Et Al

US 20150202317A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2015/0202317 A1 Rau et al. (43) Pub. Date: Jul. 23, 2015 (54) DIPEPTDE-BASED PRODRUG LINKERS Publication Classification FOR ALPHATIC AMNE-CONTAINING DRUGS (51) Int. Cl. A647/48 (2006.01) (71) Applicant: Ascendis Pharma A/S, Hellerup (DK) A638/26 (2006.01) A6M5/9 (2006.01) (72) Inventors: Harald Rau, Heidelberg (DE); Torben A 6LX3/553 (2006.01) Le?mann, Neustadt an der Weinstrasse (52) U.S. Cl. (DE) CPC ......... A61K 47/48338 (2013.01); A61 K3I/553 (2013.01); A61 K38/26 (2013.01); A61 K (21) Appl. No.: 14/674,928 47/48215 (2013.01); A61M 5/19 (2013.01) (22) Filed: Mar. 31, 2015 (57) ABSTRACT The present invention relates to a prodrug or a pharmaceuti Related U.S. Application Data cally acceptable salt thereof, comprising a drug linker conju (63) Continuation of application No. 13/574,092, filed on gate D-L, wherein D being a biologically active moiety con Oct. 15, 2012, filed as application No. PCT/EP2011/ taining an aliphatic amine group is conjugated to one or more 050821 on Jan. 21, 2011. polymeric carriers via dipeptide-containing linkers L. Such carrier-linked prodrugs achieve drug releases with therapeu (30) Foreign Application Priority Data tically useful half-lives. The invention also relates to pharma ceutical compositions comprising said prodrugs and their use Jan. 22, 2010 (EP) ................................ 10 151564.1 as medicaments. US 2015/0202317 A1 Jul. 23, 2015 DIPEPTDE-BASED PRODRUG LINKERS 0007 Alternatively, the drugs may be conjugated to a car FOR ALPHATIC AMNE-CONTAINING rier through permanent covalent bonds.