What Is the Diagnosis?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uniqueness of Pilsicainide in Class Ic Antiarrhythmics Takeshi

Uniqueness of Pilsicainide in Class Ic Antiarrhythmics Takeshi YAMASHITA, MD, Yuji MURAKAWA, MD, Kazunori SEZAKI, MD, Noriyuki HAYAMI, MD, Masashi INOUE, MD, Ei-ichi FUKUI, MD, and Masao OMATA, MD SUMMARY Pilsicainide, a class Ic agent, is known to be an effective drug particularly for treating atrial tachyarrhythmias. However, its electrophysiological effects on the atrium have not been well studied. To characterize the electrophysiologic effects of pilsicainide on atrial myocytes in class Ic drugs, we examined the effects of this drug on membrane currents in single rabbit atrial myocytes using the tight-seal whole cell voltage-clamp technique. Under the current-clamp condition, pilsicainide did not affect the action potential duration at therapeutic ranges (3ƒÊM) and slightly shortened it at higher concentrations (10ƒÊM). These observations were quite different from those with other class Ic agents including flecainide and propafenone which prolong the atrial action potential duration. The drug did not affect the resting membrane potential. Under the voltage-clamp condition, pilsicainide inhibited the transient outward current (Ito) that is more prominent in the atrium than in the ventricle in a concentra- tion-dependent manner. However, in contrast to other class Ic agents, the inhibition of Ito by pilsicainide was observed only at much higher concentra- tions (IC50-300ƒÊM) and did not affect the inactivation time-course of Ito. Moreover, the drug (10ƒÊM) did not significantly affect the Ca2+, delayed rec- tifier K+, inward rectifying K+, acetylcholine-induced K+ or ATP-sensitive K+ currents. From these results, pilsicainide could be differentiated as a pure Na+ channel blocker from other class Ic agents with diverse effects on membrane currents and should be recognized accordingly in clinical situations. -

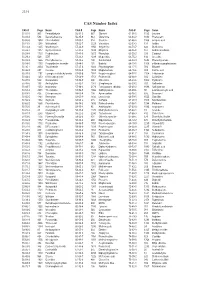

CAS Number Index

2334 CAS Number Index CAS # Page Name CAS # Page Name CAS # Page Name 50-00-0 905 Formaldehyde 56-81-5 967 Glycerol 61-90-5 1135 Leucine 50-02-2 596 Dexamethasone 56-85-9 963 Glutamine 62-44-2 1640 Phenacetin 50-06-6 1654 Phenobarbital 57-00-1 514 Creatine 62-46-4 1166 α-Lipoic acid 50-11-3 1288 Metharbital 57-22-7 2229 Vincristine 62-53-3 131 Aniline 50-12-4 1245 Mephenytoin 57-24-9 1950 Strychnine 62-73-7 626 Dichlorvos 50-23-7 1017 Hydrocortisone 57-27-2 1428 Morphine 63-05-8 127 Androstenedione 50-24-8 1739 Prednisolone 57-41-0 1672 Phenytoin 63-25-2 335 Carbaryl 50-29-3 569 DDT 57-42-1 1239 Meperidine 63-75-2 142 Arecoline 50-33-9 1666 Phenylbutazone 57-43-2 108 Amobarbital 64-04-0 1648 Phenethylamine 50-34-0 1770 Propantheline bromide 57-44-3 191 Barbital 64-13-1 1308 p-Methoxyamphetamine 50-35-1 2054 Thalidomide 57-47-6 1683 Physostigmine 64-17-5 784 Ethanol 50-36-2 497 Cocaine 57-53-4 1249 Meprobamate 64-18-6 909 Formic acid 50-37-3 1197 Lysergic acid diethylamide 57-55-6 1782 Propylene glycol 64-77-7 2104 Tolbutamide 50-44-2 1253 6-Mercaptopurine 57-66-9 1751 Probenecid 64-86-8 506 Colchicine 50-47-5 589 Desipramine 57-74-9 398 Chlordane 65-23-6 1802 Pyridoxine 50-48-6 103 Amitriptyline 57-92-1 1947 Streptomycin 65-29-2 931 Gallamine 50-49-7 1053 Imipramine 57-94-3 2179 Tubocurarine chloride 65-45-2 1888 Salicylamide 50-52-2 2071 Thioridazine 57-96-5 1966 Sulfinpyrazone 65-49-6 98 p-Aminosalicylic acid 50-53-3 426 Chlorpromazine 58-00-4 138 Apomorphine 66-76-2 632 Dicumarol 50-55-5 1841 Reserpine 58-05-9 1136 Leucovorin 66-79-5 -

Ventricular Tachycardia Drugs Versus Devices John Camm St

Cardiology Update 2015 Davos, Switzerland: 8-12th February 2015 Ventricular Arrhythmias Ventricular Tachycardia Drugs versus Devices John Camm St. George’s University of London, UK Imperial College, London, UK Declaration of Interests Chairman: NICE Guidelines on AF, 2006; ESC Guidelines on Atrial Fibrillation, 2010 and Update, 2012; ACC/AHA/ESC Guidelines on VAs and SCD; 2006; NICE Guidelines on ACS and NSTEMI, 2012; NICE Guidelines on heart failure, 2008; NICE Guidelines on Atrial Fibrillation, 2006; ESC VA and SCD Guidelines, 2015 Steering Committees: multiple trials including novel anticoagulants DSMBs: multiple trials including BEAUTIFUL, SHIFT, SIGNIFY, AVERROES, CASTLE- AF, STAR-AF II, INOVATE, and others Events Committees: one trial of novel oral anticoagulants and multiple trials of miscellaneous agents with CV adverse effects Editorial Role: Editor-in-Chief, EP-Europace and Clinical Cardiology; Editor, European Textbook of Cardiology, European Heart Journal, Electrophysiology of the Heart, and Evidence Based Cardiology Consultant/Advisor/Speaker: Astellas, Astra Zeneca, ChanRX, Gilead, Merck, Menarini, Otsuka, Sanofi, Servier, Xention, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol- Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Pfizer, Boston Scientific, Biotronik, Medtronic, St. Jude Medical, Actelion, GlaxoSmithKline, InfoBionic, Incarda, Johnson and Johnson, Mitsubishi, Novartis, Takeda Therapy for Ventricular Tachycardia Medical therapy Antiarrhythmic drugs Autonomic management Ventricular tachycardia Monomorphic Polymorphic Ventricular fibrillation Ventricular storms Ablation therapy Device therapy Surgical Defibrillation Catheter Antitachycardia pacing History of Antiarrhythmic Drugs 1914 - Quinidine 1950 - Lidocaine 1951 - Procainamide 1946 – Digitalis 1956 – Ajmaline 1962 - Verapamil 1962 – Disopyramide 1964 - Propranolol 1967 – Amiodarone 1965 – Bretylium 1972 – Mexiletine 1973 – Aprindine, Tocainide 1969 - Diltiazem 1975- Flecainide 1976 – Propafenone Encainide Ethmozine 2000 - Sotalol D-sotalol 1995 - Ibutilide (US) Recainam 2000 – Dofetilide US) IndecainideX Etc. -

Jp Xvii the Japanese Pharmacopoeia

JP XVII THE JAPANESE PHARMACOPOEIA SEVENTEENTH EDITION Official from April 1, 2016 English Version THE MINISTRY OF HEALTH, LABOUR AND WELFARE Notice: This English Version of the Japanese Pharmacopoeia is published for the convenience of users unfamiliar with the Japanese language. When and if any discrepancy arises between the Japanese original and its English translation, the former is authentic. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Ministerial Notification No. 64 Pursuant to Paragraph 1, Article 41 of the Law on Securing Quality, Efficacy and Safety of Products including Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices (Law No. 145, 1960), the Japanese Pharmacopoeia (Ministerial Notification No. 65, 2011), which has been established as follows*, shall be applied on April 1, 2016. However, in the case of drugs which are listed in the Pharmacopoeia (hereinafter referred to as ``previ- ous Pharmacopoeia'') [limited to those listed in the Japanese Pharmacopoeia whose standards are changed in accordance with this notification (hereinafter referred to as ``new Pharmacopoeia'')] and have been approved as of April 1, 2016 as prescribed under Paragraph 1, Article 14 of the same law [including drugs the Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare specifies (the Ministry of Health and Welfare Ministerial Notification No. 104, 1994) as of March 31, 2016 as those exempted from marketing approval pursuant to Paragraph 1, Article 14 of the Same Law (hereinafter referred to as ``drugs exempted from approval'')], the Name and Standards established in the previous Pharmacopoeia (limited to part of the Name and Standards for the drugs concerned) may be accepted to conform to the Name and Standards established in the new Pharmacopoeia before and on September 30, 2017. -

Translational Studies on Anti-Atrial Fibrillatory Action of Oseltamivir by Its in Vivo and in Vitro Electropharmacological Analyses

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 29 April 2021 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.593021 Translational Studies on Anti-Atrial Fibrillatory Action of Oseltamivir by its in vivo and in vitro Electropharmacological Analyses Ryuichi Kambayashi 1, Hiroko Izumi-Nakaseko 1, Ai Goto 1, Kazuya Tsurudome 2, Hironori Ohshiro 2, Taku Izumi 2, Mihoko Hagiwara-Nagasawa 1, Koki Chiba 1, Ryota Nishiyama 3, Satomi Oyama 3, Yoshio Nunoi 1, Yoshinori Takei 4, Akio Matsumoto 5 and Atsushi Sugiyama 1,4,5,6* 1Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Toho University, Tokyo, Japan, 2Sophion Bioscience K.K., Saitama, Japan, 3Drug Research Department, TOA EIYO LTD., Fukushima, Japan, 4Department of Translational Research and Cellular Therapeutics, Faculty of Medicine, Toho University, Tokyo, Japan, 5Department of Aging Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Toho University, Tokyo, Japan, 6Yamanashi Research Center of Clinical Pharmacology, Yamanashi, Japan Edited by: Oseltamivir has been shown to prolong the atrial conduction time and effective refractory Apostolos Zarros, University of Glasgow, period, and to suppress the onset of burst pacing-induced atrial fibrillation in vitro.Tobetter United Kingdom predict its potential clinical benefit as an anti-atrial fibrillatory drug, we performed translational Reviewed by: studies by assessing in vivo anti-atrial fibrillatory effect along with in vivo and in vitro Ilya Kolb, Janelia Research Campus, electropharmacological analyses. Oseltamivir in intravenous doses of 3 (n 6) and United States 30 mg/kg (n 7) was administered in conscious state to the persistent atrial fibrillation Jordi Heijman, model dogs to confirm its anti-atrial fibrillatory action. The model was prepared by tachypacing Maastricht University, Netherlands > *Correspondence: to the atria of chronic atrioventricular block dogs for 6 weeks. -

Pharmaceutical Appendix to the Tariff Schedule 2

Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2007) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2007) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 2 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. ABACAVIR 136470-78-5 ACIDUM LIDADRONICUM 63132-38-7 ABAFUNGIN 129639-79-8 ACIDUM SALCAPROZICUM 183990-46-7 ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACIDUM SALCLOBUZICUM 387825-03-8 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ACIFRAN 72420-38-3 ABAPERIDONUM 183849-43-6 ACIPIMOX 51037-30-0 ABARELIX 183552-38-7 ACITAZANOLAST 114607-46-4 ABATACEPTUM 332348-12-6 ACITEMATE 101197-99-3 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ACITRETIN 55079-83-9 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ACIVICIN 42228-92-2 ABETIMUSUM 167362-48-3 ACLANTATE 39633-62-0 ABIRATERONE 154229-19-3 ACLARUBICIN 57576-44-0 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ACLATONIUM NAPADISILATE 55077-30-0 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ACODAZOLE 79152-85-5 ABRINEURINUM 178535-93-8 ACOLBIFENUM 182167-02-8 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ACONIAZIDE 13410-86-1 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ACOTIAMIDUM 185106-16-5 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2015/0202317 A1 Rau Et Al

US 20150202317A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2015/0202317 A1 Rau et al. (43) Pub. Date: Jul. 23, 2015 (54) DIPEPTDE-BASED PRODRUG LINKERS Publication Classification FOR ALPHATIC AMNE-CONTAINING DRUGS (51) Int. Cl. A647/48 (2006.01) (71) Applicant: Ascendis Pharma A/S, Hellerup (DK) A638/26 (2006.01) A6M5/9 (2006.01) (72) Inventors: Harald Rau, Heidelberg (DE); Torben A 6LX3/553 (2006.01) Le?mann, Neustadt an der Weinstrasse (52) U.S. Cl. (DE) CPC ......... A61K 47/48338 (2013.01); A61 K3I/553 (2013.01); A61 K38/26 (2013.01); A61 K (21) Appl. No.: 14/674,928 47/48215 (2013.01); A61M 5/19 (2013.01) (22) Filed: Mar. 31, 2015 (57) ABSTRACT The present invention relates to a prodrug or a pharmaceuti Related U.S. Application Data cally acceptable salt thereof, comprising a drug linker conju (63) Continuation of application No. 13/574,092, filed on gate D-L, wherein D being a biologically active moiety con Oct. 15, 2012, filed as application No. PCT/EP2011/ taining an aliphatic amine group is conjugated to one or more 050821 on Jan. 21, 2011. polymeric carriers via dipeptide-containing linkers L. Such carrier-linked prodrugs achieve drug releases with therapeu (30) Foreign Application Priority Data tically useful half-lives. The invention also relates to pharma ceutical compositions comprising said prodrugs and their use Jan. 22, 2010 (EP) ................................ 10 151564.1 as medicaments. US 2015/0202317 A1 Jul. 23, 2015 DIPEPTDE-BASED PRODRUG LINKERS 0007 Alternatively, the drugs may be conjugated to a car FOR ALPHATIC AMNE-CONTAINING rier through permanent covalent bonds. -

Cost-Effectiveness of Rate- and Rhythm-Control Drugs for Treating Atrial Fibrillation in Korea

Original Article Yonsei Med J 2019 Dec;60(12):1157-1163 https://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2019.60.12.1157 pISSN: 0513-5796 · eISSN: 1976-2437 Cost-Effectiveness of Rate- and Rhythm-Control Drugs for Treating Atrial Fibrillation in Korea Min Kim1*, Woojin Kim2*, Changsoo Kim2,3, and Boyoung Joung1 1Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Severance Cardiovascular Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul; 2Department of Preventive Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul; 3Institute of Human Complexity and Systems Science, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea. Purpose: Although the economic and mortality burden of atrial fibrillation (AF) is substantial, it remains unclear which treat- ment strategies for rate and rhythm control are most cost-effective. Consequently, economic factors can play an adjunctive role in guiding treatment selection. Materials and Methods: We built a Markov chain Monte Carlo model using the Korean Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service database. Drugs for rate control and rhythm control in AF were analyzed. Cost-effective therapies were selected using a cost-effectiveness ratio, calculated by net cost and quality-adjusted life years (QALY). Results: In the National Health Insurance Service data, 268149 patients with prevalent AF (age ≥18 years) were identified between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2015. Among them, 212459 and 55690 patients were taking drugs for rate and rhythm control, respectively. Atenolol cost $714/QALY. Among the rate-control medications, the cost of propranolol was lowest at $487/QALY, while that of carvedilol was highest at $1363/QALY. Among the rhythm-control medications, the cost of pilsicainide was lowest at $638/QALY, while that of amiodarone was highest at $986/QALY. -

Drugs to Avoid in Brugada Syndrome Patients January 2015

Concerns: ______________________ Date of birth: ______________________ Dear colleague, Because of cardiologic and/or genetic evidence of Brugada syndrome in the patient mentioned above, I advised him/her not to take the following prescriptions: DRUGS TO BE AVOIDED Antiarrhythmic drugs*: Ajmaline, Allapinine, Ethacizine, Flecainide, Pilsicainide, Procainamide, Propafenone Psychotropic drugs: Amitriplyline, Clomipramine, Desipramine, Lithium, Loxapine, Nortriptyline, Oxcarbazepine, Trifluoperazine Anesthetics / analgesics*: Bupivacaine, Procaine, Propofol Other substances: Acetylcholine, Alcohol (toxicity), Cannabis, Cocaine, Ergonovine *For advice please visit www.brugadadrugs.org/emergencies DRUGS PREFERABLY AVOIDED Antiarrhythmic drugs: Amiodarone, Cibenzoline, Disopyramide, Lidocaine*, Propranolol, Verapamil, Vernakalant Psychotropic drugs: Bupropion, Carbamazepine, Clothiapine, Cyamemazine, Dosulepine, Doxepine, Fluoxetine, Fluvoxamine, Imipramine, Lamotrigine, Maprotiline, Paroxetine, Perphenazine, Phenytoin, Thioridazine Anesthetics / analgesics: Ketamine, Tramadol Other substances: Demenhydrinate, Diphenhydramine, Edrophonium, Indapamide, Metoclopramide, Terfenadine/Fexofenadine * Lidocaine use for local anesthesia (e.g. by dentists) does seem to be safe if the amount administrated is low and if it is combined with adrenaline (epinephrine) which results in a local effect only. Further, in case of fever, close (electrocardiographic) monitoring is appropriate in combination with lowering of the body temperature (e.g. by using Paracetamol/Acetaminophen). -

Prolonged Atrioventricular Block and Ventricular Standstill Following

Oe K Prolonged AV block with ATP Case Report Prolonged Atrioventricular Block and Ventricular Standstill Following Adenosine Triphosphate Injection in a Patient Taking Dipyridamole and Antiarrhythmic Agents: A Case Report Kotaro Oe MDÃ1, Tsutomu Araki MDÃ1, Kenshi Hayashi MDÃ2, Masakazu Yamagishi MDÃ2 Ã1Division of Internal Medicine, Saiseikai Kanazawa Hospital Ã2Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Kanazawa University Graduate School of Medicine An 83-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital because of palpitation. She had hypertension and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, treated with digoxin and cibenzoline, and took dipyridamole for microalbuminuria. Before admission, she had taken pilsicainide pills in addition. On admission, electrocardiogram showed regular tachycardia with mildly prolonged QRS width. For the purpose of terminating tachycardia, 10 mg of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) was rapidly injected. About 20 sec later, atrioventricular block and ventricular standstill occurred. She presented loss of consciousness and convulsion, and chest compression was performed. About 30 sec later, the QRS complex reappeared, and she became alert. Serum concentration of digoxin, cibenzoline and pilsicainide was within therapeutic level, respectively. We should be cautious in using ATP for a patient taking dipyridamole and antiarrhythmic agents. (J Arrhythmia 2009; 25: 219–222) Key words: Adenosine, Cardiac arrest, Antiarrhythmia agents Introduction Case Report Adenosine has been commonly used to treat An 83-year-old woman was admitted to our -

ST Segment Elevation in the Right Precordial Leads Following Administration of Class Ic Antiarrhythmic Drugs

Heart 2001;85:e3 (http://www.heartjnl.com/cgi/content/full/85/1/e3) 1of3 CASE STUDIES Heart: first published as 10.1136/heart.85.1.e3 on 1 January 2001. Downloaded from ST segment elevation in the right precordial leads following administration of class Ic antiarrhythmic drugs M Yasuda, Y Nakazato, H Yamashita, G Sekita, Y Kawano, Y Mineda, K Nakazato, T Tokano, M Sumiyoshi, Y Nakata Abstract In 1992, Brugada and Brugada1 reported a Electrocardiographic changes were evalu- study of eight patients with idiopathic ventricu- ated retrospectively in five patients without lar fibrillation who showed ST segment eleva- previous episodes of syncope or ventricular tion in the right precordial lead (the Brugada 2–4 fibrillation who developed abnormal ST syndrome). Recent studies have reported that segment elevation mimicking the Brugada class I antiarrhythmic drugs such as flecainide, syndrome in leads V1–V3 after the admin- procainamide, and ajmaline could unmask ST istration of class Ic antiarrhythmic drugs. segment elevation in patients with “latent” Bru- Pilsicainide (four patients) or flecainide gada syndrome. In addition, we reported the first case5 of a patient who had no previous syn- (one patient) were administered orally for cope or ventricular fibrillation, but who showed the treatment of symptomatic paroxysmal electrocardiographic changes mimicking those atrial fibrillation or premature atrial con- of the Brugada syndrome after administration of tractions. The QRS duration, QTc, and JT a class Ic antiarrhythmic drug. Similar cases intervals on 12 lead surface ECG before were presented by us67and others8–10 in ensuing administration of these drugs were all years. In this article we present five such patients within normal range. -

Pilsicainide Intoxication in a Patient with Dehydration

Jpn Circ J 1999; 63: 219–222 Pilsicainide Intoxication in a Patient With Dehydration Shin-ichiro Ozeki, MD; Toshinori Utsunomiya, MD*; Shuzo Matsuo, MD*; Katsusuke Yano, MD** An 81-year-old woman developed pilsicainide intoxication associated with dehydration. The patient had been taking pilsicainide (100 mg/day) for 1 year because of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Her renal function was within normal limits. One week before admission, she was suffering from pneumonia, and had appetite loss, fever, and severe fatigue. Physical examination revealed dehydration. The electrocardiogram (ECG) on admis- sion showed atrioventricular dissociation, idioventricular rhythm with marked QRS widening and QTc prolonga- tion. The plasma concentration of pilsicainide on admission was markedly elevated at 6.2μg/ml, approximately 6times the therapeutic range (0.25–1.0μg/ml). Continuous saline infusion was initiated for the treatment of dehydration,which progressively improved. As a result, sinus rhythm was recovered 2h after admission, and the QRS and JT intervals gradually normalized. This is an interesting case because the proarrhythmia of pilsicainide was induced by dehydration. (Jpn Circ J 1999; 63: 219–222) Key Words: Arrhythmia; Dehydration; Pilsicainide ilsicainide is a class Ic antiarryhthmic drug which concentration was 0.25μg/ml 12h after takin a 50mg tablet has been confirmed to be effective in the manage- orally. P ment of clinical arrhythmia.1,2 Recently, adverse Seven days before admission, she had a fever of up to effects of the class Ic antiarryhthmic drugs, such as 38°C. Over the next 7 days, fatigue and appetite loss gradu- flecainide and propafenone, have been reported.3 Overdoses ally developed.