Review of There Is No Mystery About Patents by William R. Ballard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Missing Rings: No Mystery Story

New Mexico Quarterly Volume 6 | Issue 4 Article 9 1936 The iM ssing Rings: No Mystery Story Florence M. Hawley Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmq Recommended Citation Hawley, Florence M.. "The iM ssing Rings: No Mystery Story." New Mexico Quarterly 6, 4 (1936). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ nmq/vol6/iss4/9 This Contents is brought to you for free and open access by the University of New Mexico Press at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Quarterly by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hawley: The Missing Rings: No Mystery Story The Missing Rings: No Mystery Story By FLORENCE M. HAWLEY HEN A man steals something from you, it may indicate W anything. from carelessness on your 'part to a faulty polic~ system~ or the cussedness of human nature, but when nature steals something from you, you are pitted against the gods. May the best man win! On the other hand, Dr. Douglass,'like all scientists, was stealing from nature. Nature held a secret, and Dr. "D," as his co-workers have affectionately called him, wanted it. He plotted ways and" means of obtaining data on Sijn spot occurrence in the distant past so that he could, perhaps, project it into the future. You can't picture a man plotting and planning some safe~racker's technique for obtaining data on sun spots? It does sound like considerable work for a rather dull end, and you are rightabout the work but not about the end. -

The Stanley Clarke Band SAT / JAN 18 / 7:30 PM

The Stanley Clarke Band SAT / JAN 18 / 7:30 PM Stanley Clarke BASS Cameron Graves KEYBOARDS Evan Garr VIOLIN Salar Nader TABLAS Jeremiah Collier DRUMS Lyris Quartet Alyssa Park VIOLIN Shalini Vijayan VIOLIN Luke Maurer VIOLA Timothy Loo CELLO Tonight’s program will be announced from the stage. There will be no intermission. Jazz & Blues at The Broad Stage made possible by a generous gift from Richard & Lisa Kendall. PERFORMANCES MAGAZINE 4 Naik Raj by Photo ABOUT THE ARTISTS Photo by Raj Naik Raj by Photo Four-time GRAMMY® Award winner of Philadelphia, a Doctorate from Clarke Band: UP, garnered him a 2015 STANLEY CLARKE is undoubtedly one Philadelphia’s University of the Arts GRAMMY® Award nomination for Best of the most celebrated acoustic and and put his hands in cement as a Jazz Arrangement Instrumental or A electric bass players in the world. 1999 inductee into Hollywood’s “Rock Cappella for the song “Last Train to What’s more, he is equally gifted Walk.” In 2011 he was honored with Sanity” and an NAACP Image Award as a recording artist, performer, the highly prestigious Miles Davis nomination for Best Jazz Album. composer, conductor, arranger, Award at the Montréal Jazz Festival Clarke’s CD, The Message, was producer and fi lm score composer. for his entire body of work. Clarke has released on Mack Avenue Records A true pioneer in jazz and jazz- won Downbeat magazine’s Reader’s in 2018. Clarke considers the new fusion, Clarke is particularly known and Critics Poll for Best Electric Bass album “funky, melodic, musical, for his ferocious bass dexterity Player for many years. -

Table of Contents

1 •••I I Table of Contents Freebies! 3 Rock 55 New Spring Titles 3 R&B it Rap * Dance 59 Women's Spirituality * New Age 12 Gospel 60 Recovery 24 Blues 61 Women's Music *• Feminist Music 25 Jazz 62 Comedy 37 Classical 63 Ladyslipper Top 40 37 Spoken 65 African 38 Babyslipper Catalog 66 Arabic * Middle Eastern 39 "Mehn's Music' 70 Asian 39 Videos 72 Celtic * British Isles 40 Kids'Videos 76 European 43 Songbooks, Posters 77 Latin American _ 43 Jewelry, Books 78 Native American 44 Cards, T-Shirts 80 Jewish 46 Ordering Information 84 Reggae 47 Donor Discount Club 84 Country 48 Order Blank 85 Folk * Traditional 49 Artist Index 86 Art exhibit at Horace Williams House spurs bride to change reception plans By Jennifer Brett FROM OUR "CONTROVERSIAL- SUffWriter COVER ARTIST, When Julie Wyne became engaged, she and her fiance planned to hold (heir SUDIE RAKUSIN wedding reception at the historic Horace Williams House on Rosemary Street. The Sabbats Series Notecards sOk But a controversial art exhibit dis A spectacular set of 8 color notecards^^ played in the house prompted Wyne to reproductions of original oil paintings by Sudie change her plans and move the Feb. IS Rakusin. Each personifies one Sabbat and holds the reception to the Siena Hotel. symbols, phase of the moon, the feeling of the season, The exhibit, by Hillsborough artist what is growing and being harvested...against a Sudie Rakusin, includes paintings of background color of the corresponding chakra. The 8 scantily clad and bare-breasted women. Sabbats are Winter Solstice, Candelmas, Spring "I have no problem with the gallery Equinox, Beltane/May Eve, Summer Solstice, showing the paintings," Wyne told The Lammas, Autumn Equinox, and Hallomas. -

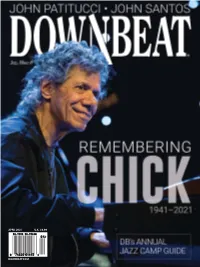

Downbeat.Com April 2021 U.K. £6.99

APRIL 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM April 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Telephone Paging System How-To Guide to System Design

Telephone Paging Systems A How-To Guide to System Design Contents Profile On Bogen . .2 Why Sell Telephone Paging? . .3 Choosing the Right System . .4 How To Design a Telephone Paging System . .8 Step 1. Does the phone system have a paging output? . .9 Step 2. Is zone paging required? . .11 Step 3. What are the sound pressure levels in the area? . .12 Step 4. What kind of speakers are required and how are they mounted? . .13 Step 5. How to determine the power taps and coverage per speaker . .20 Step 6. How to determine the appropriate amplifier . .21 Bogen Telephone Paging System Products . .23 Bogen Telephone Paging Systems Printed in U.S.A. Bogen Communications, Inc. 50 Spring Street, Ramsey, NJ 07446 Tel: 201-934-8500 Fax: 201-934-9832 Web: http://www.bogen.com 54-9133-08 9901 1 Profile On Bogen Bogen Communications, Inc., is one of the most highly regarded names in telephone paging, commercial sound and engineered systems equipment in the United States and Canada. For more than 65 years, Bogen has remained one of the leading manufacturers and designers in the field of telephone paging, public address, intercommunications and background music systems. Product reliability, value, and an aware- ness of the customers’ current and future needs have always been Bogen’s strength in the marketplace. Bogen’s telephone paging product line offers the finest and most com- plete line of telephone paging equipment available in the industry. It is designed to be easy to use and compatible with all types of telephone systems. Bogen’s product line has grown to include self-amplified and central-amplified speakers, paging amplifiers, modular zone paging equipment, and digital telephone peripheral equipment. -

WESTERN STYLE Anxieties

NICK HERMAN And God said let there be lights in the firmament of the heavens to divide the day from the night: and let them be for signs… German Bible of Martin Luther The extent to which we respond to color is simply a matter of how skillfully and purposefully color is projected at us. Advertising Agency Magazine My movie would end in sunstroke. Robert Smithson WESTERN STYLE anxieties. How these myths are perpetuated is of particular interest when discussing the West because, as I will discuss at length, it is the means by which the myth is trafficked that has become the sign of the thing itself. The West therefore has become a mirror of its motivations — the shape shifting Terminator capable of adopting any form. What Debord called our society of spectacle has eclipsed the earlier orientation of a Christian heaven and redirected our focus away from the soul to the material pursuit and the game of identity makeover. The eternal horizon has become an endless one. The known knowns 1 Packaged like the Holy Grail, the West has become not a destination as such but a lifestyle It appears that both in the visual arts and in politics, the perennial theme of the West is again embedded in the materials and images of our capitalist society. This is why politics and in ascent. That art would imitate and seek to entertain a subject as romantic as the West is not artists both use it as a backdrop and cluster around its myths, because it has become our most surprising. -

77-2440 Laborde, Charles Bernard, Jr., 1949- FORM and FORMULA in DETECTIVE DRAMA: a STRUCTURAL STUDY of SELECTED TWENTIETH- CENTURY MYSTERY PLAYS

77-2440 LaBORDE, Charles Bernard, Jr., 1949- FORM AND FORMULA IN DETECTIVE DRAMA: A STRUCTURAL STUDY OF SELECTED TWENTIETH- CENTURY MYSTERY PLAYS. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1976 Theater Xerox University Microfilms,Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 © 1976 CHARLES BERNARD LaBORDE, JR. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED FORM AND FORMULA IN DETECTIVE DRAMA* A STRUCTURAL STUDY OF SELECTED TWENTIETH-CENTURY MYSTERY PLAYS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Charles Bernard LaBorde, Jr., B.A., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 1976 Reading Committee* Approved By Donald Glancy Roy Bowen Charles Ritter ^ A'dviser Department of Theatre ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful to Professor Donald Glancy for his guidance In the writing of this dissertation and to the other members of my committee. Dr, Roy Bowen and Dr. Charles Ritter, for their criticism. I am also indebted to Dr. Clifford Ashby for suggesting to me that the topic of detective drama was suitable for exploration in a dissertation. ii VITA October 6, 19^9 .... Born - Beaumont, Texas 1971 ......... B.A., Lamar State College of Technology, Beaumont, Texas 1971-1973 .......... Teaching Assistant, Department of Speech and Theatre Arts, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas 1973 .............. M.A., Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas 1973-1975 ....... Teaching Associate, Department of Theatre, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1975-1976 ....... University Fellow, Graduate School, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio PUBLICATIONS "Sherlock Holmes on the Stage after William Gillette." Baker Street Journal. N. S., 2k (June 1974), 109-19. "Sherlock Holmes on the Stage: William Gillette," Accepted for publication by Baker Street Journal. -

Successful Teaching Newspapers Link, a Pass Code, and Directions for Retrieving $87.00 Per DVD the Item for Your Personal Use

In this newspaper, all page numbers and references to Effective teaching experts The First Days of School Harry and Rosemary Wong have been helping teachers refer to the 4th edition of become effective teachers for decades. It’s their passion, the book, except as noted. because the single greatest effect on student achievement is the effectiveness of the teacher. How to Effectively Manage Your Classroom It is no secret. A Super Successful and Effective Teacher manages a classroom with procedures and routines. PROCEDURES are used to have an organized and consistent classroom so that learning can take place. www.EffectiveTeaching.com 1. CLEARLY DEFINE CLASSROOM PROCEDURES AND ROUTINES Effective teachers teach classroom procedures by first defining, stating, demonstrating, and modeling procedures and allowing for classroom questions and understandings. TEACHING Procedures are used to structure how things are done in the classroom, such as entering the classroom, quieting the For Teachers Who Want to Be Effective classroom, getting into and doing group work, sharpening ISSUE 515 pencils, collecting papers, and the like. To learn how to teach procedures, read chapters 19 and 20 in The First Days of School, watch parts 3 and 4 of The Effective How to Get Students to Do Teacher, or read THE Classroom Management Book. What You Want Them to Do The 3 Steps to Teaching a Procedure 1. Teach: State, explain, demonstrate, and model lassroom management and discipline are not the same. Classroom management is about ORGANIZATION the procedure. and CONSISTENCY. Discipline is behavior management. You manage a store; you do not discipline a 2. -

On Campus -Construction Student Forum at 4:30 P.M

COURTSIDE COVERAGE OF WOMEN'S BASKETBALL NCAA DALLAS REGIONAL - PAGE 5 TUESDAY VOLUME 92 MARCH 27, 2007 AN INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER SERVING SOUTHERN METHODIST UNIVERSITY • DALLAS, TEXAS • SMUDAILYCAMPUS.COM WEATHER ByMarkNorris disappointment with the judge's decision in a bankruptcy filings and other legal maneuvers. Vodicka also hopes to have the case heard Editor in Chief Saturday article in the Dallas Morning News. The issue at stake in the case is breach of fi before a 12-panel jury. [email protected] The move brings the case back to the front of duciary duty, according to Vodicka. He said that According to the Morning News story, SMU the Bush Library debate, as some are saying that SMU conspired with its employees and certain plans to file for summary judgment. The univer A federal judge has sent Gary Vodicka's law it is delaying the acquisition of the complex. tenants in University Gardens to rent and even sity made a similar request in the first phase of the suit against SMU back to a state district court. Vodicka said he does not believe that is true and tually gain control of the complex. case, which was resolved in late December 2006. The move came after Vodicka asked the case be that a choice was made long ago. Vodicka said the remand would allow him to The decision allowed SMU to evict Vodicka from TODAY remanded because he dropped federal racketeer Vodicka sued SMU in August 2005 saying the have additional time to put together a case dur his condo and begin demolishing the property. -

Wilkie Collins and Copyright

Wilkie Collins and Copyright Wilkie Collins and Copyright Artistic Ownership in the Age of the Borderless Word s Sundeep Bisla The Ohio State University Press Columbus Copyright © 2013 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bisla, Sundeep, 1968– Wilkie Collins and copyright : artistic ownership in the age of the borderless word / Sundeep Bisla. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1235-6 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1235-2 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-9337-9 (cd-rom) ISBN-10: 0-8142-9337-9 (cd-rom) Collins, Wilkie, 1824–1889—Criticism and interpretation. 2. Intellectual property in literature. 3. Intellectual property—History—19th century. 4. Copyright—History—19th century. I. Title. PR4497.B57 2013 823'.8—dc23 2013010878 Cover design by Laurence J. Nozik Type set in Adobe Garamond Pro Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 s CONTENTS S Acknowledgments vii Preface A Spot of Ink, More Than a Spot of Bother ix Chapter 1 Introduction: Wilkie Collins, Theorist of Iterability 1 Part One. The Fictions of Settling Chapter 2 The Manuscript as Writer’s Estate in Basil 57 Chapter 3 The Woman in White: The Perils of Attempting to Discipline the Transatlantic, Transhistorical Narrative 110 Part Two. The Fictions of Breaking Chapter -

I ACTS and I FISI C F I

TH U RS DA Y. MA Y 1. 1980 PAGE 1A I ACTS AND I FISI C f I A Romance With Dance By JEAN MATTOCK choreographer Jose Limon, whose cers, much of the solo duty falls to horrendously-pastelled, droopy proximity of thè attractive (over- Spring -culminates in per works continue to be performed William Hansen and Delila tutus underscore the broad, but attractive) costumes against the formance for most local dance worldwide. Moseley, who also often partner never slapstick comedy. black field is surprising and ef companies; accordingly, recent In her own work, Condodina each other. Hansen has danced Bobby McFerrin’s score tran fective. Scaramouche looks more weekends have each been studded blends Limon’s emotive cathartic with Alvin Ailey and Jose Limon’s scends parody, invigorating his like a noble but forlorn Don with concerts. One evening of sdrama, expansive motivating companies, with the San Diego and chosen forms from All Feets Can Quixote as he bats his jutting grey- dance is still coming up. breath, dynamic use of weight, and California Ballets and teaches here Dance humming disco to an angst- beared chin. Repertory-West Dance Com sculptural but fluid design, with a at UCSB. Moseley has worked in ridden . Wagnerian lieder. pany, Santa Barbara’s only rhythmic depth and complexity the companies of Alvin Ailey, Movement ridiculousness — tap The koto sounds almost like a resident modern dance company that parallels the demanding but Joyce Trisler, Donald McKayle dancing on pointe,plies with the harpsichord with dynamics, and will perform at Campbell Hall on exquisite music she uses. -

THE COWL Behaviors

TheVol. LXXVIII No. 16 @thecowl • thecowl.com ProvidenceCowl College February 27, 2014 The Vagina Monologues Performed at Avon Cinema Women’s Basketball by Mary McGreal ’15 Pinks Out Gym for A&E Staff theater Cancer Research Last Saturday, members of the by Veronica Lippert ’15 Providence community gathered at Sports Staff the Avon Cinema on Thayer Street. On the uncharacteristically lovely women’s basketball February afternoon, the suitably intimate theatre buzzed with anticipation before the second of Last weekend, Providence College two performances of Eve Ensler’s held its annual Pink Game to raise The Vagina Monologues. Saturday funds and awareness for breast marked the eighth year that the cancer research. The event has been Monologues have been banned on growing steadily since it began, and campus, which have been performed took a leap forward this year with by Providence College students since events of a much larger scope. While 2003. In a 2006 letter to the Providence the culmination of the effort was the College community, Fr. Brian Women’s Basketball game on Feb. Shanley wrote, “Precisely because 22, all of PC’s women’s sports did its depiction of female sexuality is so their part. The Women’s Hockey deeply at odds with the true meaning Team kicked off PC’s efforts with and morality that the Catholic their Skating Strides event on Feb. Church’s teaching celebrates, 16. They sold pink ice skates in the The Vagina Monologues is not an lead-up to the game. These sales, appropriate play to be performed on combined with other profits from our campus.