A Brief History of the IPA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

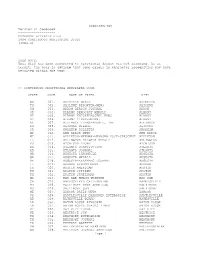

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers Asian Native Asian Native Am. Black Hisp Am. Total Am. Black Hisp Am. Total ALABAMA The Anniston Star........................................................3.0 3.0 0.0 0.0 6.1 Free Lance, Hollister ...................................................0.0 0.0 12.5 0.0 12.5 The News-Courier, Athens...........................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Lake County Record-Bee, Lakeport...............................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Birmingham News................................................0.7 16.7 0.7 0.0 18.1 The Lompoc Record..................................................20.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 The Decatur Daily........................................................0.0 8.6 0.0 0.0 8.6 Press-Telegram, Long Beach .......................................7.0 4.2 16.9 0.0 28.2 Dothan Eagle..............................................................0.0 4.3 0.0 0.0 4.3 Los Angeles Times......................................................8.5 3.4 6.4 0.2 18.6 Enterprise Ledger........................................................0.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 Madera Tribune...........................................................0.0 0.0 37.5 0.0 37.5 TimesDaily, Florence...................................................0.0 3.4 0.0 0.0 3.4 Appeal-Democrat, Marysville.......................................4.2 0.0 8.3 0.0 12.5 The Gadsden Times.....................................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Merced Sun-Star.........................................................5.0 -

![Moore County) Dixie Herald, Weekly, [1936]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0748/moore-county-dixie-herald-weekly-1936-380748.webp)

Moore County) Dixie Herald, Weekly, [1936]

North Carolina Newspaper Project Guide to Newspapers on Microfilm in the North Carolina State Archives Last updated April 2018 Please submit questions or corrections to Chris Meekins at 919-814-6870. The North Carolina Newspaper Project, a joint effort of the North Carolina Division of Historical Resources and the State Library of North Carolina, is part of the United States Newspaper Program. Partial funding has been provided by the Office of Preservation, National Endowment for the Humanities. 109 E. Jones Street, Raleigh, NC 27601 email: [email protected] www.archives.ncdcr.gov phone: 919-814-6840 ABERDEEN (Moore County) Dixie Herald, weekly, [1936]. AbeDH-1, partial reel. Absorbed by the Pilot December 1936. Pilot, weekly, 1929-1949. AbeP, 10 reels. Farmers' Union Bulletin, monthly, [1918]. WsnMISC-1, partial reel. Published in Wilson, with news for Aberdeen. Sandhill Citizen, weekly, [1915-1917, 1919], 1920, 1921, [1931, 1933, 1934], 1954- 1968.. A continuation of the Southern Pines Tourist. Continued by the Sandhill Citizen Consolidated. (Includes the SOUTHERN PINES Sandhill Citizen) SpSC, 10 reels. The Telegram, 3/17/1899. GMISC-71. ADVANCE (Davie County) Hornet. See BIXBY, Hornet. BxMISC-1, partial reel. AHOSKIE (Hertford County) Daily Roanoke-Chowan News, daily, 1947-1962. AshDRCN, 21 reels. Hertford County Herald, semiweekly, [1939], 1953-1962. AshHCH, 5 reels. ALBEMARLE (Stanly County) Albemarle Chronicle, weekly [1912-1913], semiweekly [1913-1917]. AbmAC, 2 reels. Albemarle Enterprise, weekly, 1912-1919, 1947-1949, [1950-1951],1952-1955, [1956]. AbmAE, 7 reels. Albemarle Index, weekly, [1906]. AbmMISC-1, partial reel. Albemarle Press, weekly, [1922-1929]. AbmAP, 3 reels. Albemarle Tribune, weekly, [1937-1938]. -

Henderson County Multi-Jurisdictional Natural Hazards Mitigation Plan

Henderson County Multi-jurisdictional Natural Hazards Mitigation Plan Village of Biggsville Village of Media Village of Gladstone Village of Oquawka Village of Gulfport Village of Raritan Village of Lomax Village of Stronghurst January 2010 Henderson County Multi-jurisdictional Natural Hazards Mitigation Plan Plan Author: University of Illinois Extension With Assistance from: Illinois State Water Survey Western Illinois Regional Council Contributing Staff University of Illinois Extension: Earl Bricker, Program Director, Community Assessment & Development Services Stephanie Dehart, Extension Unit Educator, Pike County Zachary Kennedy, Outreach Associate, Community Assessment & Development Services Al Kulczewski, County Extension Director, Henderson County Carrie McKillip, Extension Unit Educator, Knox County James Mortland, Outreach Assistant, Community Assessment & Development Services Illinois State Water Survey: Kingsley Allan, GIS Manager Lisa Graff, HAZUS-MH Projects Lead Brad McVay, GIS Specialist January 2010 The preparation of this report was financed through a Hazard Mitigation Grant Program Planning Grant from the Federal Emergency Management Agency and by Henderson County. Henderson County Multi-jurisdictional Natural Hazards Mitigation Plan Task Force NAME REPRESENTING Alexander, James Village of Gladstone Bowman, Terri Camden Township Butler, Revonne Henderson County Zoning Clifton, Richard Self Interest Cochran, Brian Village of Biggsville Cole, Karen Bridgeway Mental Health Doran, Tom Henderson County EDC Eisenmayer, Curt -

Obituary Index 3Dec2020.Xlsx

Last First Other Middle Maiden ObitSource City State Date Section Page # Column # Notes Naber Adelheid Carrollton Gazette Carrolton IL 9/26/1928 1 3 Naber Anna M. Carrollton Gazette Patriot Carrolton IL 9/23/1960 1 2 Naber Bernard Carrollton Gazette Carrolton IL 11/17/1910 1 6 Naber John B. Carrollton Gazette Carrolton IL 6/13/1941 1 1 Nace Joseph Lewis Carthage Republican Carthage IL 3/8/1899 5 2 Nachtigall Elsie Meler Chicago Daily News Chicago IL 3/27/1909 15 1 Nachtigall Henry C. Chicago Daily News Chicago IL 11/30/1909 18 4 Nachtigall William C. Chicago Daily News Chicago IL 10/5/1925 38 3 Nacke Mary Schleper Effingham Democrat Effingham IL 8/6/1874 3 4 Nacofsky Lillian Fletcher Chicago Daily News Chicago IL 2/22/1922 29 1 Naden Clifford Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 11/8/1990 Countywide 2 2 Naden Earl O. Waukegan News Sun Waukegan IL 11/2/1984 7A 4 Naden Elizabeth Broadbent Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 1/17/1900 8 4 Naden Isaac Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 2/28/1900 4 1 Naden James Darby Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 12/25/1935 4 5 Naden Jane Green Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 4/10/1912 9 3 Naden John M. Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 9/13/1944 5 4 Naden Martha Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 12/6/1866 3 1 Naden Obadiah Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 11/8/1911 1 1 Naden Samuel Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 6/17/1942 7 1 Naden Samuel Mrs Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 8/15/1878 4 3 Naden Samuel Mrs Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 8/8/1878 1 4 Naden Thomas Kendall County -

Newspapers October 2009 Central Illinois Teaching with Primary Sources Newsletter

Newspapers October 2009 Central Illinois Teaching with Primary Sources Newsletter EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY SOUTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY EDWARDSVILLE CONTACTS We got the scoop: newspapers • Melissa Carr [email protected] Editor • Cindy Rich [email protected] • Amy Wilkinson [email protected] INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Topic Introduction 2 Connecting to Illinois 3 Learn More with 4 American Memory In the Classroom 6 Test Your Knowledge 7 Images Sources 9 www.eiu.edu/~eiutps/newsletter Page 2 Newspapers We got the scoop: Newspapers Welcome to the 24th issue of the Central Illinois of the Revolutionary War there were 37 independent Teaching with Primary Sources Newsletter a American newspapers. collaborative project of Teaching with Primary Sources In an attempt to deal with Great Britain's enormous Programs at Eastern Illinois University and Southern national debt, England passed the Stamp Act in 1765, Illinois University Edwardsville. Our goal is to bring you which taxed all paper documents. This tax included the topics that connect to the Illinois Learning Standards as American colonies since they were under British control. well as provide you with amazing items from the Library This was met with great resistance in the colonies. of Congress. The Industrial Revolution changed the newspaper Newspapers are mentioned specifically within ISBE industry. With the introduction of printing presses, materials for the following Illinois Learning Standards newspapers were able to print at a much faster pace and (found within goal, standard, benchmark or performance higher quantity. This meant that more pages could be descriptors) 1.A-Apply word analysis and vocabulary skills added to the newspapers so local news could be to comprehend selections. -

Appendix File 1984 Continuous Monitoring Study (1984.S)

appcontm.txt Version 01 Codebook ------------------- CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE 1984 CONTINUOUS MONITORING STUDY (1984.S) USER NOTE: This file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As as result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. >> CONTINUOUS MONITORING NEWSPAPER CODE STATE CODE NAME OF PAPER CITY WA 001. ABERDEEN WORLD ABERDEEN TX 002. ABILENE REPORTER-NEWS ABILENE OH 003. AKRON BEACON JOURNAL AKRON OR 004. ALBANY DEMOCRAT-HERALD ALBANY NY 005. ALBANY KNICKERBOCKER NEWS ALBANY NY 006. ALBANY TIMES-UNION, ALBANY NE 007. ALLIANCE TIMES-HERALD, THE ALLIANCE PA 008. ALTOONA MIRROR ALTOONA CA 009. ANAHEIM BULLETIN ANAHEIM MI 010. ANN ARBOR NEWS ANN ARBOR WI 011. APPLETON-NEENAH-MENASHA POST-CRESCENT APPLETON IL 012. ARLINGTON HEIGHTS HERALD ARLINGTON KS 013. ATCHISON GLOBE ATCHISON GA 014. ATLANTA CONSTITUTION ATLANTA GA 015. ATLANTA JOURNAL ATLANTA GA 016. AUGUSTA CHRONICLE AUGUSTA GA 017. AUGUSTA HERALD AUGUSTA ME 018. AUGUSTA-KENNEBEC JOURNAL AUGUSTA IL 019. AURORA BEACON NEWS AURORA TX 020. AUSTIN AMERICAN AUSTIN TX 021. AUSTIN CITIZEN AUSTIN TX 022. AUSTIN STATESMAN AUSTIN MI 023. BAD AXE HURON TRIBUNE BAD AXE CA 024. BAKERSFIELD CALIFORNIAN BAKERSFIELD MD 025. BALTIMORE NEWS AMERICAN BALTIMORE MD 026. BALTIMORE SUN BALTIMORE ME 027. BANGOR DAILY NEWS BANGOR OK 028. BARTLESVILLE EXAMINER-ENTERPRISE BARTLESVILLE AR 029. BATESVILLE GUARD BATESVILLE LA 030. BATON ROUGE ADVOCATE BATON ROUGE LA 031. BATON ROUGE STATES TIMES BATON ROUGE MI 032. BAY CITY TIMES BAY CITY NE 033. BEATRICE SUN BEATRICE TX 034. BEAUMONT ENTERPRISE BEAUMONT TX 035. BEAUMONT JOURNAL BEAUMONT PA 036. -

Eugene Field's Years As. a Chicago Journalist (1883-1895)

EUGENE FIELD'S YEARS AS. A CHICAGO JOURNALIST (1883-1895) Thesis for the Degree of M. A. MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY PATRICIA LILLIAN WALKER 1969 ABSTRACT EUGENE FIELD'S YEARS AS A CHICAGO JOURNALIST (1883-1895) by Patricia Lillian Walker This is a study of the historical importance and contributions of Eugene Field to the era of Chicago jour- nalism that produced such journalists and literary figures as George Ade,rFinley Peter Dunne, Theodore Dreiser, and later Carl Sandburg and Edgar Lee Masters, and such edi- tors as Melville Stone, Slason Thompson, and Wilbur Storey. Field's quick fame and definition as a children's poet has obscured his contributions as a humorist and journalist, his life-time occupation. This study re-examines Eugene Field in light of his career in journalism which reached its greatest height and importance as editorial columnist for the Chicago Daily News. It is based on the newspaper files of the Chicago Daily News, biographies, literary criticisms, and other sources of the period, and on pri- vate papers and special collections relating to Field's acquaintances. Accepted by the faculty of the School of Journalism, College of Communications Arts, Michigan State University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree. EUGENE FIELD'S YEARS AS A CHICAGO JOURNALIST (1883-1895) BY Patricia Lillian Walker A THESIS Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS School of Journalism 1969 Copyright by PATRICIA LILLIAN WALKER 1969 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The unpublished materials and collections and the microfilms of newspapers from the period used in this study were obtained through the permission of the Chicago Public Library and the Chicago Historical Society. -

America's Oldest Daily Newspaper. the New York Globe

COLUMBIA LIBRARIES OFFSITE AVERY FINE ARTS RESTRICTED AR01414356 AMERICA'S OLDEST DAILY NEWSPAPER itx Htbrts SEYMOUR DURST 'i ' 'Tort nieuiu i^im/ierdam. of Je Manhatan^ IVhen you leave, please leave this book Because it has been said "Ever'ihing comes t' him who waits £:<cept a loaned book." AVI.KY Al<( HI I I.C TUKAl, AND FiNI-. AK IS 1,1HRARN (ill ! oi Si;ym()UR B. Dursi Oi d York I.ihr \R^ I.%pf'i AMERICA'S OLDEST DAILY NEWSPAPER AMERICA'S OLDEST DAILY NEWSPAPER. THE NEW YORK GLOBE Founded December 9, 1793, by Noah Webster, as the ^'American Minerva." Renamed ''The Commercial Advertiser" October 7, 1797. Renamed ''The Globe and Commercial Advertiser" February 1, 1904. ©fe^^^Jll?''^ The Oldest Continuous Daily Newspaper on the American Continent. AMERICA'S OLDEST DAILY NEWSPAPER reprinting the historical and institutional matter contained IN in the 125th Anniversary Number of the New York Globe for more permanent preservation than its publication in the newspaper, it is hoped that we have produced a little book which may be a pleasing addition to the libraries of our friends. The Globe seeks to be more than a mere newspaper. With its historical background, reaching to the earliest days of our country as a nation, it is almost as firmly founded as the Unites States itself as an institution for sound, accurate, and independent con- sideration and treatment of the news and affairs of the day. The Globe is justly proud of its long years of successful oper- ation, and, as will be seen by reference to the contents of this book, is to-day a greater and more influential institution than at any time in its long career. -

Newspaper Distribution List

Newspaper Distribution List The following is a list of the key newspaper distribution points covering our Integrated Media Pro and Mass Media Visibility distribution package. Abbeville Herald Little Elm Journal Abbeville Meridional Little Falls Evening Times Aberdeen Times Littleton Courier Abilene Reflector Chronicle Littleton Observer Abilene Reporter News Livermore Independent Abingdon Argus-Sentinel Livingston County Daily Press & Argus Abington Mariner Livingston Parish News Ackley World Journal Livonia Observer Action Detroit Llano County Journal Acton Beacon Llano News Ada Herald Lock Haven Express Adair News Locust Weekly Post Adair Progress Lodi News Sentinel Adams County Free Press Logan Banner Adams County Record Logan Daily News Addison County Independent Logan Herald Journal Adelante Valle Logan Herald-Observer Adirondack Daily Enterprise Logan Republican Adrian Daily Telegram London Sentinel Echo Adrian Journal Lone Peak Lookout Advance of Bucks County Lone Tree Reporter Advance Yeoman Long Island Business News Advertiser News Long Island Press African American News and Issues Long Prairie Leader Afton Star Enterprise Longmont Daily Times Call Ahora News Reno Longview News Journal Ahwatukee Foothills News Lonoke Democrat Aiken Standard Loomis News Aim Jefferson Lorain Morning Journal Aim Sussex County Los Alamos Monitor Ajo Copper News Los Altos Town Crier Akron Beacon Journal Los Angeles Business Journal Akron Bugle Los Angeles Downtown News Akron News Reporter Los Angeles Loyolan Page | 1 Al Dia de Dallas Los Angeles Times -

To: WIU's Board of Trustees and Student Publications Board Feb. 2

To: WIU’s Board of Trustees and Student Publications Board Feb. 2, 2015 This is from a few folks who care about Western Illinois University and about Freedom of the Press. As you may know, WIU’s student newspaper, the Western Courier, has a history of producing good work and good alumni, from Civil Rights pioneer C.T. Vivian and Fulbright Scholar David Heinz to Pulitzer Prize- winning reporter Mark Konkol and hundreds of lesser-known contributors. It’s faced challenges ranging from being kicked off campus (it survived) and a libel lawsuit (it prevailed) to returning to campus (it improved) and threats of withholding funds or pressure from Sherman Hall (…). As you may not know, WIU Vice President Gary Biller’s Jan. 22 suspension of Courier editor Nicholas Stewart, because his freelance report on a Dec. 12 campus fracas was picked up by other media, has caused considerable commotion on campus and beyond, with objections by individuals and groups of journalists, First Amendment advocates and everyday citizens. Biller wrote that Stewart “poses a threat to the normal operations of the University” (a surprising charge when real problems exist, such as inadequate state support and enrollment). Biller accuses the undergrad of “committing acts of dishonesty [such as] attempting to represent the University, any recognized student organization, or any official University group without the explicit prior consent of the officials of that group”; “engaging in act of theft or abuse of computer time including … unauthorized financial gain or commercial activity”; and “committing violations of rules and regulations duly established and promulgated by other University departments,” all under the Code of Student Conduct. -

Whpr19761012-026

,- PAN AMEaiAN WHITE HOUSE PRESS CHARTER OCTOB·12-13, 1976 TO NEW YORK, NEW YORK AND RETURN -------------------------------------- WIRES: Howard Benedict Associated Press Don Rothberg Associated Press Richard Growald United Press International Arnold Sawislak United Press International Ralph Harr~s Reuters Louis Foy Agence France Presse NEWSPAPERS: Ed Walsh Washington Post Jack Germond Washington Star Muriel Dobbin Baltimore Sun Sandy Grady Philadelphia Bulletin Lucien Warren Buffalo Evening News Charles Mohr New York Times James Wieghart New York Daily News Clyde Haberman New York Post (Jn NYC) Dennis Farney Wall Street Journal Marty Schram News day Alan Emory Watertown (NY) Times (Jn NYC) Al Blanchard Detroit News Rick Zimmerman Cleveland Plain Dealer Curtis Wilkie Boston Globe Mort Kondracke Chicago Sun- Times (Off NYC) Aldo Beckman Chicago Tribune Robert Gruenberg Chicago Daily News Richard Dudman St. Louis Post-Dispatch Gaylord Shaw Los Angeles Times Rudy Abramson Los Angeles Times John Geddie Dallas Morning News Judy Wieseler Houston Chronicle Saul Kohler Newhouse Newspapers Art Wiese Houston Post Henry Gold Kansas City Star (Off NYC) Al Sullivan United States Information Agency Richard Maloy Thomson Newspapers (Off Newark) Don Campbell Gannett Newspapers Joseph Kraft Field Newspaper Syndicate (Jn NYC only' Steve Mitchell Cox Newspapers Andrew Glass Cox Newspapers Joe Albright Cox Newspapers (Jn NYC) Benjamin Shore Copley News Service Tom Tiede NEA-Scripps -Howard (Off NYC) William Broom Ridder Ted Knap Scripps-Howard Robert Boyd Knight Newspapers Lester Kinsolving United Features/WAVA Peter Loesche SPD-Rundschau MAGAZINES: Pierre Salinger L'Express Strobe Talbott Time James Dowell Newsweek John Mashek U.S. News & World Report Michael Grossman Joh11s Hopkins Press Martha Kumar Johns Hopkins Press John Buckley Western Union Digitized from Box 32 of the White House Press Releases at the Gerald R. -

Table 6: Details of Race and Ethnicity in Newspaper

Table 6 Details of race and ethnicity in newspaper circulation areas All daily newspapers, by state and city Source: Report to the Knight Foundation, June 2005, by Bill Dedman and Stephen K. Doig The full report is at http://www.asu.edu/cronkite/asne (The Diversity Index is the newsroom non-white percentage divided by the circulation area's non-white percentage.) (DNR = Did not report) State Newspaper Newsroom Staff non-Non-white Hispanic % Black % in Native Asian % in Other % in Multirace White % in Diversity white % % in in circulation American circulation circulation % in circulation Index circulation circulation area % in area area circulation area (100=parity) area area circulation area area Alabama The Alexander City Outlook N/A DNR 26.8 0.6 25.3 0.3 0.2 0.0 0.5 73.2 Alabama The Andalusia Star-News 175 25.0 14.3 0.8 12.3 0.5 0.2 0.0 0.6 85.7 Alabama The Anniston Star N/A DNR 20.7 1.4 17.6 0.3 0.5 0.1 0.8 79.3 Alabama The News-Courier, Athens 0 0.0 15.7 2.8 11.1 0.5 0.4 0.0 0.9 84.3 Alabama Birmingham Post-Herald 29 11.1 38.5 3.6 33.0 0.2 1.0 0.1 0.7 61.5 Alabama The Birmingham News 56 17.6 31.6 1.8 28.1 0.3 0.8 0.1 0.7 68.4 Alabama The Clanton Advertiser 174 25.0 14.4 2.9 10.4 0.3 0.2 0.0 0.6 85.6 Alabama The Cullman Times N/A DNR 4.5 2.1 0.9 0.4 0.2 0.0 0.9 95.5 Alabama The Decatur Daily 44 8.6 19.7 3.1 13.2 1.6 0.4 0.0 1.4 80.3 Alabama The Dothan Eagle 15 4.0 27.3 1.9 23.1 0.5 0.6 0.1 1.0 72.8 Alabama Enterprise Ledger 68 16.7 24.4 2.7 18.2 0.9 1.0 0.1 1.4 75.6 Alabama TimesDaily, Florence 89 12.1 13.7 2.1 10.2 0.3 0.3 0.0 0.7