ARTICLE American Movie Audiences of the 1930S1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vision, Desire and Economies of Transgression in the Films of Jess Franco

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 1 Journeys into Perversion: Vision, Desire and Economies of Transgression in the Films of Jess Franco Glenn Ward Doctor of Philosophy University of Sussex May 2011 2 I hereby declare that this thesis has not been, and will not be, submitted whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature:……………………………………… 3 Summary Due to their characteristic themes (such as „perverse‟ desire and monstrosity) and form (incoherence and excess), exploitation films are often celebrated as inherently subversive or transgressive. I critically assess such claims through a close reading of the films of the Spanish „sex and horror‟ specialist Jess Franco. My textual and contextual analysis shows that Franco‟s films are shaped by inter-relationships between authorship, international genre codes and the economic and ideological conditions of exploitation cinema. Within these conditions, Franco‟s treatment of „aberrant‟ and gothic desiring subjectivities appears contradictory. Contestation and critique can, for example, be found in Franco‟s portrayal of emasculated male characters, and his female vampires may offer opportunities for resistant appropriation. -

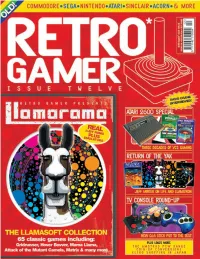

Retro Gamer Speed Pretty Quickly, Shifting to a Contents Will Remain the Same

Untitled-1 1 1/9/06 12:55:47 RETRO12 Intro/Hello:RETRO12 Intro/Hello 14/9/06 15:56 Page 3 hel <EDITORIAL> >10 PRINT "hello" Editor = >20 GOTO 10 Martyn Carroll >RUN ([email protected]) Staff Writer = Shaun Bebbington ([email protected]) Art Editor = Mat Mabe Additonal Design = Mr Beast + Wendy Morgan Sub Editors = Rachel White + Katie Hallam Contributors = Alicia Ashby + Aaron Birch Richard Burton + Keith Campbell David Crookes + Jonti Davies Paul Drury + Andrew Fisher Andy Krouwel + Peter Latimer Craig Vaughan + Gareth Warde Thomas Wilde <PUBLISHING & ADVERTISING> Operations Manager = Debbie Whitham Group Sales & Marketing Manager = Tony Allen hello Advertising Sales = elcome Retro Gamer speed pretty quickly, shifting to a contents will remain the same. Linda Henry readers old and new to monthly frequency, and we’ve We’ve taken onboard an enormous Accounts Manager = issue 12. By all even been able to publish a ‘best amount of reader feedback, so the Karen Battrick W Circulation Manager = accounts, we should be of’ in the shape of our Retro changes are a direct response to Steve Hobbs celebrating the magazine’s first Gamer Anthology. My feet have what you’ve told us. And of Marketing Manager = birthday, but seeing as the yet to touch the ground. course, we want to hear your Iain "Chopper" Anderson Editorial Director = frequency of the first two or three Remember when magazines thoughts on the changes, so we Wayne Williams issues was a little erratic, it’s a used to be published in 12-issue can continually make the Publisher = little over a year old now. -

Film Calendar

FILM CALENDAR JULY 26 - OCTOBER 3, 2019 ONCE UPON A TIME… IN HOLLYWOOD *ON 70MM* OPENS JULY 26 JENNIFER KENT’S THE NIGHTINGALE OPENS AUGUST 16 NOIR CITY CHICAGO SEPTEMBER 6-12 GIVE ME LIBERTY A MUSIC BOX FILMS RELEASE OPENS SEPTEMBER 13 DORIS DAY WEEKEND MATINEES SEPTEMBER 15-29 Music Box Theatre 90th Anniversary Celebration August 22 - 29 Welcome TO THE MUSIC BOX THEATRE! FEATURE FILMS 5 ONCE UPON A TIME… IN HOLLYWOOD OPENS JULY 26 7 LUZ OPENS AUGUST 2 7 HONEYLAND OPENS AUGUST 9 8 THE NIGHTINGALE OPENS AUGUST 16 CHICAGO 9 AQUARELA OPENS AUGUST 30 ONSCREEN 9 GIVE ME LIBERTY OPENS SEPTEMBER 13 12 MONOS OPENS SEPTEMBER 20 A traveling exhibition of MUSIC BOX 90TH ANNIVERSARY Chicago-made film 16 INNOCENTS OF PARIS AUGUST 22 17 THE FUGITIVE AUGUST 23 18 WORLD CITY IN ITS TEENS AUGUST 24 18 DOLLY PARTON 9 TO 5ER AUGUST 24 19 MARY POPPINS SING-A-LONG AUGUST 25 19 INDIE HORROR: SOCIETY AUGUST 25 20 MUSIC BOX FILMS DOUBLE FEATURE AUGUST 27 21 AUDIENCE CHOICE DOUBLE FEATURE AUGUST 28 22 70MM: BACK TO THE FUTURE II AUGUST 29 24 THE HISTORY OF THE MUSIC BOX SERIES 28 BETTE DAVIS MATINEES 30 DORIS DAY MATINEES 30 SILENT CINEMA 08.26-08.28 32 CHICAGO FILM SOCIETY NEIGHBORHOOD 34 MIDNIGHTS SHOWCASE SCREENINGS Dunbar Park | Grant Park | Horner Park SPECIAL EVENTS Jackson Park | Margate Park | Mckinley Park 6 GALLAGHER WAY MOVIE SERIES MAY - SEPTEMBER Steelworkers Park | Wicker Park 6 DISCOVER THE HORROR JULY 27 8 RUSH: CINEMA STRANGIATO AUGUST 21 08.29-08.31 10 NOIR CITY SEPTEMBER 6-12 CHICAGO ONSCREEN FESTIVAL 11 SAY AMEN, SOMEBODY SEPTEMBER 14 & 15 Humboldt Park | Three days of local films from filmmakers 11 REELING FILM FESTIVAL OPENING SEPTEMBER 19 and film organizations from all over the city in a multi-screen 12 48 HOUR FILM PROJECT SEPTEMBER 22-25 festival celebration of movies by and about Chicago. -

Day Two,San Diego Comic-Con 2013 – Day One

Scene and Heard Mary Loss of Soul There is no accurate description of the whirling dervish I met recently on the set of her soon-to-be- released film, Mary Loss of Soul. It was the last day of shooting, and the energy level and passion of this female director was boundless – and infectious! The woman I speak of is Jennifer B. White. She is a writer, director and producer – but she’ll tell you she is first and foremost a storyteller. “I was ten years old. I’d never heard the term “folktale” – a narrated story to entertain a group of listeners. But, that’s exactly how I began my creative dream – as a storyteller in the woods. Back in the day of knock-on-door neighborhoods in the suburbs of Massachusetts, I’d gather with a group of wide-eyed kids along with my side-kick little sister. I told stories – often about ghosts, witches and anything spooky – making them up as I went along. I started writing novels at the age of 12 on my mom’s old IBM Selectric. As the family keeper of all things old and nostalgic, I held on to those precious works of fiction like they were a buccaneer’s booty.” After college, Jennifer signed with her first literary agent, and went on to become a public relations professional heading up PR in Boston hotels and top agencies where she was published in hundreds of publications throughout the U.S. She continued writing novels throughout her career, and, through a series of fortunate encounters, began writing for Hollywood. -

Downloading, Or Streaming Them on Mobile Devices

UCLA UCLA Previously Published Works Title “Parasite Cinema,” Image and Narrative, special issue on Artaud and Cruelty, 17.5 (2016), 66-79 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/32j321fb Authors Ravetto-Biagioli, K Beugnet, M Publication Date 2019-10-18 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Martine Beugnet and Kriss Ravetto-Biagioli Parasite Cinema Abstract In Theatre and its Double Artaud explored how the plague communicates beyond simple contact, bringing death to those it touches, but also bringing fear, images, and the imagination, which transforms social rela- tions, disorganising society and producing absurd anti-social actions. In this essay we would like to relate the emergence of a parasite-cinema, one that expresses itself through predatory forms of capture and communica- tion, where images pullulate out of control (but do not destroy the body of the host), to Artaud’s understanding of plague as a proliferation of communication. Résumé Dans Le Théâtre et son double Artaud analyse la manière dont la peste communique au-delà du seul contact physique, apportant la mort à ceux qu’elle touche, mais apportant aussi la peur, des images et l’imagination qui transforme les rapports sociaux, désorganisant la société et produisant des comportements absurdes anti-so- ciaux. Dans cet essai nous nous proposons de mettre en rapport la conception artaudienne de la peste comme forme proliférante de communication avec l’émergence d’une nouvelle forme de cinéma, le cinéma parasite, qui s’exprime à travers des formes prédatrices de capture et de communication, des images qui pullulent en dehors de tout contrôle (mais sans détruire le corps de celui qui les accueille). -

Cultural Materialism in the Production and Distribution of Exploitative Lesbian Film: a Historical Case Study of Children of Loneliness (1935)

Cultural Materialism in the Production and Distribution of Exploitative Lesbian Film: A Historical Case Study of Children of Loneliness (1935) Anna Fåhraeus, Halmstad University Abstract Raymond Williams developed a vocabulary and framework for analyzing the ideological forces at work in literature and art, as objects, but also in terms of their production and distribution. This article looks back at his elaboration of cultural materialism and its relationship to film in Preface to Film (1954), written with Michael Orrin, as a way of understanding the media traces of the lost film Children of Loneliness (dir. Richard C. Kahn). The film was an early sex education about homosexuality and this article explores its connections to early exploitation films as a cinematic form, and the dominant and emergent discourses that were used to promote it, as a well as at structures of feeling that these discourses reflect. Keywords: structure of feeling; history of film; Children of Loneliness; homosexuality ‘To be truly radical is to make hope possible rather than despair convincing.’ Raymond Williams1 Introduction Raymond Williams laid much of the groundwork for cultural studies and media studies with his work Culture and Society (1958), Communications (1962) and Television (1974). It is less well-known that from his university days in the 1930s he also worked with film and produced several important texts for Film Studies, including ‘Film as a Tutorial Subject’ (1953) and the volume, Preface to Film (1954), co- authored with his friend, the documentary filmmaker Michael Orrin. The book was a manifesto for the political potential of the form. Williams’s contribution was an essay entitled, ‘Film and the Dramatic Tradition.’ The main thrust is that in order to study the moving image as a cultural form, it needs to be understood in relation to the history of drama (Dolan 1 Resources of Hope, published posthumously (1989: 118). -

Neo-Exploitation

Neo-exploitation Nostalgia for horrific wonders Martijn van Hoek 0304964 Blok 4 2011/2012 22-06-2012 Thema: Genre Begeleider: J.S. Hurley Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................... 3 Exploring exploitation and nostalgia ......................................................................... 4 Exploring horror fan culture .................................................................................... 6 Exploring neo-exploitation .....................................................................................13 Redefining a genre................................................................................................13 GRINDHOUSE ..........................................................................................................14 CABIN FEVER ..........................................................................................................15 IRRÉVERSIBLE .........................................................................................................17 Conclusion ...........................................................................................................18 Literature ............................................................................................................19 2 Introduction In the first decade of the new millennium, a section of the horror genre was not looking to the future, but instead drew inspiration from the past. A number of filmmakers looked to the exploitation films of the -

October 2018

The Bijou Film Board is a student-run UI organization dedicated to the exhibition of American independent, foreign and classic cinema. The Bijou assists FilmScene with program curation and operations. FilmScene Staff Joe Tiefenthaler, Executive Director Andrew Sherburne, Associate Director BIJOU PROGRAMMING IS FREE FOR UI STUDENTS $6.50 GENERAL PUBLIC Rebecca Fons, Programming Director Emily Salmonson, Dir. of Operations AFTER HOURS A late-night series featuring cult HORIZONS A cinematic FILM FORUM Acclaimed and provocative films, Ross Meyer, Head Projectionist classics, fan favorites, recent releases, and modern genre world tour. Attend for a paired with discussions in cooperation with University and Facilities Manager films. Saturdays at 11pm. chance to win a scholarship! of Iowa departments and student groups. Connie White, Film Booker Aaron Holmgren, Operations Asst. Dominick Shults, Projection and WHICH WAY Facilities Assistant HOME (2009) Dir. Abby Thomas, Marketing Assistant Rebecca Cammisa. SAT, 10/6 SAT, Theater Staff: Graham Bly, TUE, 10/9 TUE, 10/2 SAT, 10/13 SAT, This documentary Adam Bryant, Emma Gray, film follows several Galen Hawthorne, Jack Howard, YOUNG ZOMBIELAND TOMBOY (2011) unaccompanied child Max Johnson, Emily Stagman FRANKENSTEIN (2009) Dir. Ruben Dir. Celine Sciamma. migrants as they Projectionists: Jack Christensen, (1974) Dir. Mel Brooks. Fleischer. A shy guy, a A family moves into journey to the U.S. Mac Chuchra, Felipe Disarz, The grandson of an tough guy and a two a new neighborhood, Tristen Kopp, Aaron Longoria, infamous scientist is sisters join forces to and 10-year-old Laure CHICAGOLAND Michael Wawzenek invited to Transylvania travel across a zombie- deliberately presents as SHORTS VOL. -

FILM GUIDEFEATURE FILMS 2040 April 16-17

Ashland Independent Film Festival 2021 Schedule of Events April 15-29 virtual and June 24-28 live & outdoors Entire Film Schedule & Descriptions Inside TicketsTickets $$8-8-$$1212 WatchWatch atat homehome andand outdoorsoutdoors inin MedfordMedford && AshlandAshland ashlandfilm.orgashlandfilm.org ANCHOR POINT written and produced by Holly Tuckett 2 / ASHLANDFILM.ORG ASHLAND INDEPENDENT FILM FESTIVAL 2021 SCHEDULE OF EVENTS / 3 April 15-29 virtual June 24-28 live & outdoors 20th Anniversary FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR MEET THE AIFF 2021 TEAM Greetings, returning and first-time festival goers! Last year, AIFF was compelled Artistic Director Richard Herskowitz to call off its live April festival at the last minute, for obvious reasons. We quickly Executive Director Erica Thompson resurrected ourselves as a virtual festival in May, and it went incredibly well. People told us how much they appreciated the interactivity and community spirit Membership Manager Candace Turtle we sustained by featuring fascinating Q&A’s with every program and by offering Communications and Development Assistant Susannah Cole opportunities for filmmaker-audience interaction through our online parties and Communications Manager Heather Barta social media. Office Coordinator Paige Gerhard For our 20th anniversary festival, we are planning a double feature–a virtual Systems Manager Lisa Greene festival in April and a live outdoors festival in June. We are evolving into a Programming and Hospitality Coordinator Chloe Ordway hybrid festival that lights the way toward -

The Critical-Industrial Practices of Contemporary Horror Cinema

Off-Screen Scares: The Critical-Industrial Practices of Contemporary Horror Cinema A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Joseph F Tompkins IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Richard Leppert, Adviser January 2013 © Joseph F Tompkins, 2013 Acknowledgements I would like to extend my thanks to the many friends, colleagues, teachers, and family members who provided the necessary support and advice to usher me through both the dissertation writing process and my time as a graduate student. I am grateful to the members of my dissertation committee: Mary Vavrus, Gil Rodman, John Mowitt and Gary Thomas, for their lasting guidance, scholarly advice, and critical feedback. In particular, this project was hatched in Mary Vavrus’s Political Economy of Media seminar, and for that, I’m especially indebted. Also, to Gary Thomas, who taught me, among other things, the power of good, clean prose as well as the radical possibilities of making the classroom into a vitalizing, “heterotopian” space—a rampart against the “mechanical encrustation on the living.” I would also like to convey my sincerest appreciation to my mentor, Richard Leppert, who, since my earliest days as an undergraduate, has been a source of both professional guidance and companionship. Richard is my model—as an educator and a friend. I would also like to thank Jochen Schulte-Sasse, Robin Brown, Cesare Casarino, Liz Kotz, Keya Ganguly, Timothy Brennan, Siobhan Craig, and Laurie Ouellette for their sage advice during my graduate studies. Many friends and colleagues provided me intellectual and emotional support throughout the years: Mathew Stoddard, Tony Nadler, Alice Leppert, Manny Wessels, Mark Martinez, Doyle “Mickey” Greene, Kathie Smith, and Eleanor McGough. -

PLANNING Sland

DEPARTMENT OF EXECUTIVE OFFICES CITY PLANNING ....,ITY OF Los ANGELE-...- OFFICE OF HISTORIC RESOURCES CALIFORNIA S. GAIL GOLDBERG, AICP DIRECTOR 200 N. SPRING STREET, ROOM 620 (213) 978-1271 Los ANGELES, CA 90012-4801 (213) 978-1200 JOHN M. DUGAN DEPUTY DIRECTOR CULTURAL HERITAGE COMMISSION (213) 978-1274 RICHARD BARRON PRESIDEN1 ROELLA H. LOUIE EVA YUAN-McDANIEL VICE-PRESIDEN1 DEPUTY DIRECTOR (213) 978-1273 GLEN C. DAKE ANTONIO R. VILLARAIGOSA FAX: (213) 978-1275 MIA M. LEHRER oz scorr MAYOR INFORMATION LOURDES SANCHEZ (213) 978-1270 COMMISSION EXECUTIVE ASSIST AN1 • (213) 978-1300 www.lacity.orglPLN April 22, 2008 Los Angeles City Council CORRECTED LETTER Room 395, City Hall (Case Number Only) 200 North Spring Street Los Angeles, California 90012 ATTENTION: Barbara Greaves, Legislative Assistant Planning and Land Use Management Committee CASE NUMBER: CHC-200+ 2008-12S-HCM UCLAN-CREST THEATER 1262 SOUTH WESTWOOD BOULEVARD At the Cultural Heritage Commission meeting of March 20, 2008, the Commission moved to include the above property in the list of Historic-Cultural Monuments and exclude the stage, curtains and concession stands, subject to adoption by the City Council. As required under the provisions of Section 22.171.10 of the Los Angeles Administrative Code, the Commission has solicited opinions and information from the office of the Council District in which the site is located and from· any Department or Bureau of the city whose operations may be affected by the designation of such site as a Historic-Cultural Monument. Such designation in and of itself has no fiscal impact. Future applications for permits may cause minimal administrative costs. -

Genre/Form Terms for Library and Archival Materials (LCGFT)

Library of Congress Genre/Form Terms for Library and Archival Materials LCGFT Moving Image Genre-Form Terms Updated through August 17, 2015 (List 8) Compiled by Scott M. Dutkiewicz, Cataloger, Metadata and Monographic Resources Team, Clemson University Libraries, [email protected]. Available at the OLAC website: http://olacinc.org/drupal/capc_files/GenreFormHeadingsList.pdf or in Classification Web, Genre/Form headings. Source: Cataloging Policy and Support Office, Summary of Decisions, Editorial Meeting Number 35- (August 29, 2007- present) Instruction sheet H 1913: http://www.loc.gov/catdir/cpso/h1913.pdf “Frequently asked questions about LC genre/form headings”: http://www.loc.gov/catdir/cpso/genre_form_faq.pdf A guide that provides scope notes for all the terms is available at: https://clemson.box.com/s/ncbj8ebo19i0zxhyujfob0l07dfyc1v7 Be aware that character and franchise genre/form terms were cancelled. See the PSD paper http://www.loc.gov/catdir/cpso/character_franchise_disposition_112211.pdf. Be aware that specific sports films and television terms were cancelled in List 6 (June 18, 2012). The instruction [Not Subd Geog] may not appear after each term. Genre/form terms do not subdivide geographically. If so, use coding to indicate local application. Changes in this issue New terms: Conspiracy films; Punk films; Kammerspiel films New scope: None New references to: Rock films; Western films Cancelled terms: none Genre-Form Terms 3-D films [Not Subd Geog] [gf2011026096] 455 UF Stereoscopic films 455 UF Three-dimensional films Abstract films [Not Subd Geog] [gf2011026004] 680 This heading is used as a genre/form heading for nonrepresentational films that avoid narrative and instead convey impressions and emotions by way of color, rhythm and movement.