Downloading, Or Streaming Them on Mobile Devices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARTICLE American Movie Audiences of the 1930S1

ARTICLE American Movie Audiences of the 1930s1 Richard Butsch Rider University Abstract The Depression and movies with sound changed movie audiences of the 1930s from those of the 1920s and earlier. Sound silenced audiences, discouraging the sociabili- ty that had marked working-class audiences before. The Depression led movie com- panies to change marketing strategies and construction plans. They stopped selling luxury and building movie palaces. Instead, they expanded their operation of neigh- borhood theaters, displacing independents that had been more worker friendly, and instituted centrally controlled show bills and policies. Audiences also appear to have become more heterogeneous. All this, too, discouraged the voluble behavior of working-class people. Ironically, in this era of labor activism, workers and their fam- ilies seem to have become quieter in movie theaters, satisfied with the convenience of chain-operated movie houses. The 1930s were an exciting decade for labor activism in the United States and a high point for the growth of unions. Workers in steel, automobile, and other heavy industries organized industrial unions. The Committee on Industrial Or- ganization (later Congress of Industrial Organizations or CIO) was formed with a membership of more than a million workers. Factory workers initiated new tactics in struggles with employers, such as sit-down strikes. In politics, they ad- vanced legislation and programs in the New Deal to help employed and unem- ployed workers. Ironically, at the same time that workers’ collective action and class con- sciousness were at a high point, movie audiences became quiet. They did not act collectively to control their experience in the theater. -

Katalog Dwa Brzegi 2009:Layout 1.Qxd

katalog_dwa_brzegi_2009:Layout 1 2009-07-24 08:11 Strona 1 katalog_dwa_brzegi_2009:Layout 1 2009-07-24 08:11 Strona 2 Sponsor Generalny Sponsorzy Oficjalny Oficjalny Hotel Samochód Festiwalu Festiwalu PRZYJACIELE FESTIWALU Partnerzy 2 FRIENDS FESTIVAL’S Organizatorzy Kazimierz Dolny Patronat Medialny katalog_dwa_brzegi_2009:Layout 1 2009-07-24 08:11 Strona 3 FILM AND ART FESTIVAL TWO RIVERSIDES Kazimierz Dolny Janowiec n/ Wisłą Festiwal Filmu i Sztuki DWA BRZEGI katalog_dwa_brzegi_2009:Layout 1 2009-07-24 08:11 Strona 4 katalog_dwa_brzegi_2009:Layout 1 2009-07-24 08:11 Strona 5 Spis treści | Content Przyjaciele Festiwalu | Festival’s Friends 2 Kto jest kto | Who Is Who 6 Wstęp | Foreword 9 FILM Świat pod namiotem | World Under Canvas 12 Dokument | Documentary 30 Na krótką metę | In the Short Run 38 Serial animowany | Animated Series 78 Na krótką metę na Zamku w Janowcu | In the Short Run (Screenings In the Castle in Janowiec) 80 Muzyka, moja miłość | Music My Love 84 Pokaz specjalny | Special Screening 90 Krystyna Janda. I Bóg stworzył aktorkę | And the God Created an Actress 92 Kocham kino | I Love Cinema 98 Wielkie kino na Małym Rynku | Great Cinema on Small Market Square 106 Retrospektywa Pawła Kłuszancewa | Retrospective of Pawel Klushantsev 112 W hołdzie Janowi Machulskiemu | Tribute to Jan Machulski 120 Dzień z Piotrem Szulkinem | A Day with Piotr Szulkin 122 Krótka retrospektywa Bruno Baretto | A Short Retrospective of Bruno Baretto 126 Lekcje kina | Cinema Lessons 128 Video • 130 TEATR | THEATRE CONTENT Krystyna Janda. I Bóg stworzył -

Vision, Desire and Economies of Transgression in the Films of Jess Franco

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 1 Journeys into Perversion: Vision, Desire and Economies of Transgression in the Films of Jess Franco Glenn Ward Doctor of Philosophy University of Sussex May 2011 2 I hereby declare that this thesis has not been, and will not be, submitted whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature:……………………………………… 3 Summary Due to their characteristic themes (such as „perverse‟ desire and monstrosity) and form (incoherence and excess), exploitation films are often celebrated as inherently subversive or transgressive. I critically assess such claims through a close reading of the films of the Spanish „sex and horror‟ specialist Jess Franco. My textual and contextual analysis shows that Franco‟s films are shaped by inter-relationships between authorship, international genre codes and the economic and ideological conditions of exploitation cinema. Within these conditions, Franco‟s treatment of „aberrant‟ and gothic desiring subjectivities appears contradictory. Contestation and critique can, for example, be found in Franco‟s portrayal of emasculated male characters, and his female vampires may offer opportunities for resistant appropriation. -

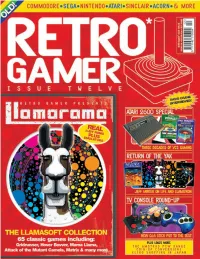

Retro Gamer Speed Pretty Quickly, Shifting to a Contents Will Remain the Same

Untitled-1 1 1/9/06 12:55:47 RETRO12 Intro/Hello:RETRO12 Intro/Hello 14/9/06 15:56 Page 3 hel <EDITORIAL> >10 PRINT "hello" Editor = >20 GOTO 10 Martyn Carroll >RUN ([email protected]) Staff Writer = Shaun Bebbington ([email protected]) Art Editor = Mat Mabe Additonal Design = Mr Beast + Wendy Morgan Sub Editors = Rachel White + Katie Hallam Contributors = Alicia Ashby + Aaron Birch Richard Burton + Keith Campbell David Crookes + Jonti Davies Paul Drury + Andrew Fisher Andy Krouwel + Peter Latimer Craig Vaughan + Gareth Warde Thomas Wilde <PUBLISHING & ADVERTISING> Operations Manager = Debbie Whitham Group Sales & Marketing Manager = Tony Allen hello Advertising Sales = elcome Retro Gamer speed pretty quickly, shifting to a contents will remain the same. Linda Henry readers old and new to monthly frequency, and we’ve We’ve taken onboard an enormous Accounts Manager = issue 12. By all even been able to publish a ‘best amount of reader feedback, so the Karen Battrick W Circulation Manager = accounts, we should be of’ in the shape of our Retro changes are a direct response to Steve Hobbs celebrating the magazine’s first Gamer Anthology. My feet have what you’ve told us. And of Marketing Manager = birthday, but seeing as the yet to touch the ground. course, we want to hear your Iain "Chopper" Anderson Editorial Director = frequency of the first two or three Remember when magazines thoughts on the changes, so we Wayne Williams issues was a little erratic, it’s a used to be published in 12-issue can continually make the Publisher = little over a year old now. -

Like Someone in Love

1 MK2 & Eurospace present A film by Abbas Kiarostami INTERNATIONAL PRESS INTERNATIONAL SALES Vanessa Jerrom & Claire Vorger MK2 11 rue du Marché Saint-Honoré - 75001 Paris (France) 55 rue Traversière - 75012 Paris (France) Email: [email protected] Juliette Schrameck - [email protected] Cell: +33 6 14 83 88 82 (Vanessa Jerrom) Dorothée Pfistner - [email protected] Cell: +33 6 20 10 40 56 (Claire Vorger) Victoire Thevenin - [email protected] In Cannes : Five Hotel 1 rue Notre-Dame - 06400 Cannes France Photos and presskit can be downloaded on www.mk2pro.com 2 3 synopsis An old man and a young woman meet in Tokyo. She knows nothing about him, he thinks he knows her. He welcomes her into his home, she offers him her body. But the web that is woven between them in the space of twenty-four hours bears no relation to the circumstances of their encounter. 4 5 new awakening Without doubt, there was an underlying sense of gnawing depravity that surfaced in Certified Copy and took me by surprise. I was sure that I already had a good understanding of the work of this film-maker that I have been lucky enough to come across so often in the past 25 years. So I was not expecting his latest film to outstrip the already high opinion I have of his work. Some people like to feel that they can describe and pigeonhole his films as ‘pseudo-simplistic modernism’. But Abbas’ films have never failed to surprise and now here, not for the first time, is a new wake-up call, for me, and I am sure many others. -

Film Calendar

FILM CALENDAR JULY 26 - OCTOBER 3, 2019 ONCE UPON A TIME… IN HOLLYWOOD *ON 70MM* OPENS JULY 26 JENNIFER KENT’S THE NIGHTINGALE OPENS AUGUST 16 NOIR CITY CHICAGO SEPTEMBER 6-12 GIVE ME LIBERTY A MUSIC BOX FILMS RELEASE OPENS SEPTEMBER 13 DORIS DAY WEEKEND MATINEES SEPTEMBER 15-29 Music Box Theatre 90th Anniversary Celebration August 22 - 29 Welcome TO THE MUSIC BOX THEATRE! FEATURE FILMS 5 ONCE UPON A TIME… IN HOLLYWOOD OPENS JULY 26 7 LUZ OPENS AUGUST 2 7 HONEYLAND OPENS AUGUST 9 8 THE NIGHTINGALE OPENS AUGUST 16 CHICAGO 9 AQUARELA OPENS AUGUST 30 ONSCREEN 9 GIVE ME LIBERTY OPENS SEPTEMBER 13 12 MONOS OPENS SEPTEMBER 20 A traveling exhibition of MUSIC BOX 90TH ANNIVERSARY Chicago-made film 16 INNOCENTS OF PARIS AUGUST 22 17 THE FUGITIVE AUGUST 23 18 WORLD CITY IN ITS TEENS AUGUST 24 18 DOLLY PARTON 9 TO 5ER AUGUST 24 19 MARY POPPINS SING-A-LONG AUGUST 25 19 INDIE HORROR: SOCIETY AUGUST 25 20 MUSIC BOX FILMS DOUBLE FEATURE AUGUST 27 21 AUDIENCE CHOICE DOUBLE FEATURE AUGUST 28 22 70MM: BACK TO THE FUTURE II AUGUST 29 24 THE HISTORY OF THE MUSIC BOX SERIES 28 BETTE DAVIS MATINEES 30 DORIS DAY MATINEES 30 SILENT CINEMA 08.26-08.28 32 CHICAGO FILM SOCIETY NEIGHBORHOOD 34 MIDNIGHTS SHOWCASE SCREENINGS Dunbar Park | Grant Park | Horner Park SPECIAL EVENTS Jackson Park | Margate Park | Mckinley Park 6 GALLAGHER WAY MOVIE SERIES MAY - SEPTEMBER Steelworkers Park | Wicker Park 6 DISCOVER THE HORROR JULY 27 8 RUSH: CINEMA STRANGIATO AUGUST 21 08.29-08.31 10 NOIR CITY SEPTEMBER 6-12 CHICAGO ONSCREEN FESTIVAL 11 SAY AMEN, SOMEBODY SEPTEMBER 14 & 15 Humboldt Park | Three days of local films from filmmakers 11 REELING FILM FESTIVAL OPENING SEPTEMBER 19 and film organizations from all over the city in a multi-screen 12 48 HOUR FILM PROJECT SEPTEMBER 22-25 festival celebration of movies by and about Chicago. -

Cgcinéma Presents

CGCINÉMA PRESENTS A FILM BY OLIVIERASSAYAS PHOTO © CAROLE BÉTHUEL CGCINÉMA PRESENTS JULIETTEBINOCHE KRISTENSTEWART CHLOË GRACEMORETZ A FILM BY OLIVIERASSAYAS 123 MIN – COLOr – 2.35 – DOLBY SRD 5.1 – 2014 PHOTO © CAROLE BÉTHUEL At the peak of her international career, Maria Enders (Juliette Binoche) is asked to perform in a revival of the play that made her famous twenty years ago. But back then she played the role of Sigrid, an alluring young girl who disarms and eventually drives her boss Helena to suicide. Now she is being asked to step into the other role, that of the older Helena. She departs with her assistant (Kristen Stewart) to rehearse in Sils Maria; a remote region of the Alps. A young Hollywood starlet with a penchant for scandal (Chloë Grace Moretz) is to take on the role of Sigrid, and Maria finds herself on the other side of the mirror, face to face with an ambiguously charming woman who is, in essence, an unsettling reflection of herself. SYNOPSIS 3 DIRECTOr’snote PHOTO © CAROLE BÉTHUEL © CAROLE PHOTO DIRECTOr’snote This film, which deals with the past, our relationship to our own past, long time. and to what forms us, has a long history. One that Juliette Binoche Writing is a path, and this one is found at dizzying heights, of time and I implicitly share. suspended between origin and becoming. It is no surprise that it We first met at the beginning of both our careers. Alongside André inspired in me images of mountainscapes and steep trails. There Téchiné, I had written Rendez-vous, a story filled with ghosts where, at needed to be Spring light, the transparency of air, and the fogs of age twenty, she had the lead role. -

| Generational Frontiers |

CON L’ADESIONE DEL PRESIDENTE DELLA REPUBBLICA Fondazione Ente dello Spettacolo via G. Palombini, 6 - 00165 Roma - Tel. +39.06.96519200 - Fax +39.06.96519220 [email protected] - www.tertiomillenniofilmfest.org | GENERATIONAL FRONTIERS | CON IL SOSTEGNO DI: IN COLLABORAZIONE CON: SPONSOR: 14 PROGRAMMA | PROGRAMME | Cinema Sala Trevi - Vicolo del Puttarello, 25 - Roma | | GENERATIONAL FRONTIERS | dicembre | december 2010 dicembre | december 2010 08 EVENTO SPECIALE | SPECIAL EVENT 09 VARIAZIONI SUL TEMA | 16.30 VARIATIONS ON THE THEME Intonazija. Sergej Slonimskij, kompositor 16.30 dicembre | december 2010 di | by Aleksandr Sokurov | 45’ Park Mark EVENTO SPECIALE | SPECIAL EVENT di | by Baktash Abtin | 42’ 07 EVENTO SPECIALE | SPECIAL EVENT Introduce | Introducing by Federico Pontiggia 16.30 17.30 Intonazija. Boris Averin, filolog Intonazija. Vladimir Yakunin, president OAO EVENTO SPECIALE | SPECIAL EVENT di | by Aleksandr Sokurov | 33’ Rossijskie železnye dorogi 18.15 EVENTO SPECIALE | SPECIAL EVENT di | by Aleksandr Sokurov | 45’ Intonazija. Boris Averin, filolog di | by Aleksandr Sokurov | 33’ 17.00 EVENTO SPECIALE | SPECIAL EVENT Intonazija. Arsen Kanokov, 18.30 EVENTO SPECIALE | SPECIAL EVENT president respubliki Kabardino-Balkaria WEDNESDAY Intonazija. Valerij Zor’kin, predsedatel’ 19.00 di | by Aleksandr Sokurov | 41’ | Konstituzionnogo suda Rossijskoj Federazii Intonazija. Arsen Kanokov, 18.00 di | by Aleksandr Sokurov | 50’ president respubliki Kabardino-Balkaria THURSDAY di | by Aleksandr Sokurov | 41’ Incontro con | Meeting with TESTIMONIANZE | PERSONAL STORIES | | Ornella Muti e | and Andrea Facchinetti 20.00 20.00 20.00 La morte rouge Incontro con | Meeting with TUESDAY Incontro con | Meeting with Aleksandr Sokurov di | by Víctor Erice | 32’ Mahamat-Saleh Haroun | 2010 | | | e presentazione del libro | and book presentation: Introduce | Introducing by Alberto Barbera Modera | Chairman Valerio Sammarco Osservare l’incanto. -

Day Two,San Diego Comic-Con 2013 – Day One

Scene and Heard Mary Loss of Soul There is no accurate description of the whirling dervish I met recently on the set of her soon-to-be- released film, Mary Loss of Soul. It was the last day of shooting, and the energy level and passion of this female director was boundless – and infectious! The woman I speak of is Jennifer B. White. She is a writer, director and producer – but she’ll tell you she is first and foremost a storyteller. “I was ten years old. I’d never heard the term “folktale” – a narrated story to entertain a group of listeners. But, that’s exactly how I began my creative dream – as a storyteller in the woods. Back in the day of knock-on-door neighborhoods in the suburbs of Massachusetts, I’d gather with a group of wide-eyed kids along with my side-kick little sister. I told stories – often about ghosts, witches and anything spooky – making them up as I went along. I started writing novels at the age of 12 on my mom’s old IBM Selectric. As the family keeper of all things old and nostalgic, I held on to those precious works of fiction like they were a buccaneer’s booty.” After college, Jennifer signed with her first literary agent, and went on to become a public relations professional heading up PR in Boston hotels and top agencies where she was published in hundreds of publications throughout the U.S. She continued writing novels throughout her career, and, through a series of fortunate encounters, began writing for Hollywood. -

0X0a I Don't Know Gregor Weichbrodt FROHMANN

0x0a I Don’t Know Gregor Weichbrodt FROHMANN I Don’t Know Gregor Weichbrodt 0x0a Contents I Don’t Know .................................................................4 About This Book .......................................................353 Imprint ........................................................................354 I Don’t Know I’m not well-versed in Literature. Sensibility – what is that? What in God’s name is An Afterword? I haven’t the faintest idea. And concerning Book design, I am fully ignorant. What is ‘A Slipcase’ supposed to mean again, and what the heck is Boriswood? The Canons of page construction – I don’t know what that is. I haven’t got a clue. How am I supposed to make sense of Traditional Chinese bookbinding, and what the hell is an Initial? Containers are a mystery to me. And what about A Post box, and what on earth is The Hollow Nickel Case? An Ammunition box – dunno. Couldn’t tell you. I’m not well-versed in Postal systems. And I don’t know what Bulk mail is or what is supposed to be special about A Catcher pouch. I don’t know what people mean by ‘Bags’. What’s the deal with The Arhuaca mochila, and what is the mystery about A Bin bag? Am I supposed to be familiar with A Carpet bag? How should I know? Cradleboard? Come again? Never heard of it. I have no idea. A Changing bag – never heard of it. I’ve never heard of Carriages. A Dogcart – what does that mean? A Ralli car? Doesn’t ring a bell. I have absolutely no idea. And what the hell is Tandem, and what is the deal with the Mail coach? 4 I don’t know the first thing about Postal system of the United Kingdom. -

Cultural Materialism in the Production and Distribution of Exploitative Lesbian Film: a Historical Case Study of Children of Loneliness (1935)

Cultural Materialism in the Production and Distribution of Exploitative Lesbian Film: A Historical Case Study of Children of Loneliness (1935) Anna Fåhraeus, Halmstad University Abstract Raymond Williams developed a vocabulary and framework for analyzing the ideological forces at work in literature and art, as objects, but also in terms of their production and distribution. This article looks back at his elaboration of cultural materialism and its relationship to film in Preface to Film (1954), written with Michael Orrin, as a way of understanding the media traces of the lost film Children of Loneliness (dir. Richard C. Kahn). The film was an early sex education about homosexuality and this article explores its connections to early exploitation films as a cinematic form, and the dominant and emergent discourses that were used to promote it, as a well as at structures of feeling that these discourses reflect. Keywords: structure of feeling; history of film; Children of Loneliness; homosexuality ‘To be truly radical is to make hope possible rather than despair convincing.’ Raymond Williams1 Introduction Raymond Williams laid much of the groundwork for cultural studies and media studies with his work Culture and Society (1958), Communications (1962) and Television (1974). It is less well-known that from his university days in the 1930s he also worked with film and produced several important texts for Film Studies, including ‘Film as a Tutorial Subject’ (1953) and the volume, Preface to Film (1954), co- authored with his friend, the documentary filmmaker Michael Orrin. The book was a manifesto for the political potential of the form. Williams’s contribution was an essay entitled, ‘Film and the Dramatic Tradition.’ The main thrust is that in order to study the moving image as a cultural form, it needs to be understood in relation to the history of drama (Dolan 1 Resources of Hope, published posthumously (1989: 118). -

Festival Catalogue 2015

Jio MAMI 17th MUMBAI FILM FESTIVAL with 29 OCTOBER–5 NOVEMBER 2015 1 2 3 4 5 12 October 2015 MESSAGE I am pleased to know that the 17th Jio MAMI Mumbai Film Festival is being organised by the Mumbai Academy of Moving Image (MAMI) in Mumbai from 29th October to 5th November 2015. Mumbai is the undisputed capital of Indian cinema. This festival celebrates Mumbai’s long and fruitful relationship with cinema. For the past sixteen years, the festival has continued promoting cultural and MRXIPPIGXYEP I\GLERKI FIX[IIR ½PQ MRHYWXV]QIHME TVSJIWWMSREPW ERH GMRIQE IRXLYWMEWXW%W E QYGL awaited annual culktural event, this festival directs international focus to Mumbai and its continued success highlights the prominence of the city as a global cultural capital. I am also happy to note that the 5th Mumbai Film Mart will also be held as part of the 17th Mumbai Film Festival, ensuring wider distribution for our cinema. I congratulate the Mumbai Academy of Moving Image for its continued good work and renewed vision and wish the 17th Jio MAMI Mumbai Film Festival and Mumbai Film Mart grand success. (CH Vidyasagar Rao) 6 MESSAGE Mumbai, with its legacy, vibrancy and cultural milieu, is globally recognised as a Financial, Commercial and Cultural hub. Driven by spirited Mumbaikars with an indomitable spirit and great affection for the city, it has always promoted inclusion and progress whilst maintaining its social fabric. ,SQIXSXLI,MRHMERH1EVEXLM½PQMRHYWXV]1YQFEMMWXLIYRHMWTYXIH*MPQ'ETMXEPSJXLIGSYRXV] +MZIRXLEX&SPP][SSHMWXLIQSWXTVSPM½GMRHYWXV]MRXLI[SVPHMXMWSRP]FI½XXMRKXLEXE*MPQ*IWXMZEP that celebrates world cinema in its various genres is hosted in Mumbai.