Cd1b in Review: High TCR Specificity Limits Auto-Reactivity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse

Welcome to More Choice CD Marker Handbook For more information, please visit: Human bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/humancdmarkers Mouse bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/mousecdmarkers Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse CD3 CD3 CD (cluster of differentiation) molecules are cell surface markers T Cell CD4 CD4 useful for the identification and characterization of leukocytes. The CD CD8 CD8 nomenclature was developed and is maintained through the HLDA (Human Leukocyte Differentiation Antigens) workshop started in 1982. CD45R/B220 CD19 CD19 The goal is to provide standardization of monoclonal antibodies to B Cell CD20 CD22 (B cell activation marker) human antigens across laboratories. To characterize or “workshop” the antibodies, multiple laboratories carry out blind analyses of antibodies. These results independently validate antibody specificity. CD11c CD11c Dendritic Cell CD123 CD123 While the CD nomenclature has been developed for use with human antigens, it is applied to corresponding mouse antigens as well as antigens from other species. However, the mouse and other species NK Cell CD56 CD335 (NKp46) antibodies are not tested by HLDA. Human CD markers were reviewed by the HLDA. New CD markers Stem Cell/ CD34 CD34 were established at the HLDA9 meeting held in Barcelona in 2010. For Precursor hematopoetic stem cell only hematopoetic stem cell only additional information and CD markers please visit www.hcdm.org. Macrophage/ CD14 CD11b/ Mac-1 Monocyte CD33 Ly-71 (F4/80) CD66b Granulocyte CD66b Gr-1/Ly6G Ly6C CD41 CD41 CD61 (Integrin b3) CD61 Platelet CD9 CD62 CD62P (activated platelets) CD235a CD235a Erythrocyte Ter-119 CD146 MECA-32 CD106 CD146 Endothelial Cell CD31 CD62E (activated endothelial cells) Epithelial Cell CD236 CD326 (EPCAM1) For Research Use Only. -

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion Genes Data Set

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion genes data set PROBE Entrez Gene ID Celera Gene ID Gene_Symbol Gene_Name 160832 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 223658 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 212988 102 hCG40040.3 ADAM10 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 10 133411 4185 hCG28232.2 ADAM11 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 11 110695 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 195222 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 165344 8751 hCG20021.3 ADAM15 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 15 (metargidin) 189065 6868 null ADAM17 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17 (tumor necrosis factor, alpha, converting enzyme) 108119 8728 hCG15398.4 ADAM19 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 19 (meltrin beta) 117763 8748 hCG20675.3 ADAM20 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 20 126448 8747 hCG1785634.2 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 208981 8747 hCG1785634.2|hCG2042897 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 180903 53616 hCG17212.4 ADAM22 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 22 177272 8745 hCG1811623.1 ADAM23 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 23 102384 10863 hCG1818505.1 ADAM28 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 28 119968 11086 hCG1786734.2 ADAM29 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 29 205542 11085 hCG1997196.1 ADAM30 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 30 148417 80332 hCG39255.4 ADAM33 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 33 140492 8756 hCG1789002.2 ADAM7 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 7 122603 101 hCG1816947.1 ADAM8 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 8 183965 8754 hCG1996391 ADAM9 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 9 (meltrin gamma) 129974 27299 hCG15447.3 ADAMDEC1 ADAM-like, -

Cd1b Tetramers Bind T Cell Receptors to Identify a Mycobacterial

Published August 1, 2011 Brief Definitive Report CD1b tetramers bind T cell receptors to identify a mycobacterial glycolipid- reactive T cell repertoire in humans Anne G. Kasmar,1 Ildiko van Rhijn,1,2 Tan-Yun Cheng,1 Marie Turner,3 Chetan Seshadri,1 Andre Schiefner,4 Ravi C. Kalathur,4 John W. Annand,1 Annemieke de Jong,1 John Shires,5 Luis Leon,1 Michael Brenner,1 Ian A. Wilson,4 John D. Altman,5 and D. Branch Moody1 1Division of Rheumatology, Immunology and Allergy, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115 2Department of Infectious Diseases and Immunology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht University, 3508 TD Utrecht, Netherlands 3Tuberculosis Treatment Unit, Lemuel Shattuck Hospital, Jamaica Plain, MA 02130 4Department of Molecular Biology and Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology, the Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA 92037 Downloaded from 5Emory Vaccine Center, Atlanta, GA 30329 Microbial lipids activate T cells by binding directly to CD1 and T cell receptors (TCRs) or by indirect effects on antigen-presenting cells involving induction of lipid autoantigens, CD1 transcription, or cytokine release. To distinguish among direct and indirect mechanisms, we developed fluorescent human CD1b tetramers and measured T cell staining. CD1b tetramer staining of T cells requires glucose monomycolate (GMM) antigens, is specific for TCR jem.rupress.org structure, and is blocked by a recombinant clonotypic TCR comprised of TRAV17 and TRBV4-1, proving that CD1b–glycolipid complexes bind the TCR. GMM-loaded tetramers brightly stain a small subpopulation of blood-derived cells from humans infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, providing direct detection of a CD1b-reactive T cell reper- toire. -

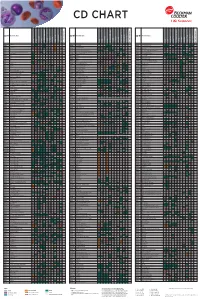

Flow Reagents Single Color Antibodies CD Chart

CD CHART CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells CD1a T6, R4, HTA1 Act p n n p n n S l CD99 MIC2 gene product, E2 p p p CD223 LAG-3 (Lymphocyte activation gene 3) Act n Act p n CD1b R1 Act p n n p n n S CD99R restricted CD99 p p CD224 GGT (γ-glutamyl transferase) p p p p p p CD1c R7, M241 Act S n n p n n S l CD100 SEMA4D (semaphorin 4D) p Low p p p n n CD225 Leu13, interferon induced transmembrane protein 1 (IFITM1). p p p p p CD1d R3 Act S n n Low n n S Intest CD101 V7, P126 Act n p n p n n p CD226 DNAM-1, PTA-1 Act n Act Act Act n p n CD1e R2 n n n n S CD102 ICAM-2 (intercellular adhesion molecule-2) p p n p Folli p CD227 MUC1, mucin 1, episialin, PUM, PEM, EMA, DF3, H23 Act p CD2 T11; Tp50; sheep red blood cell (SRBC) receptor; LFA-2 p S n p n n l CD103 HML-1 (human mucosal lymphocytes antigen 1), integrin aE chain S n n n n n n n l CD228 Melanotransferrin (MT), p97 p p CD3 T3, CD3 complex p n n n n n n n n n l CD104 integrin b4 chain; TSP-1180 n n n n n n n p p CD229 Ly9, T-lymphocyte surface antigen p p n p n -

Targeting EZH2 Increases Therapeutic Efficacy of PD-1 Check-Point Blockade in Models of Prostate Cancer Supplement Figures and T

Targeting EZH2 Increases Therapeutic Efficacy of PD-1 Check-Point Blockade in Models of Prostate Cancer Supplement Figures and Tables 1 Fig. S1. (A) Schema and genotyping PCR example for the creation of EM and EMC genetically engineered mice. (B) Three-dimensional PCa organoids generated from EM mice (without PSACreERT2) alleles. When treated with tamoxifen, demonstrates no loss of H3K27me3 or EDU staining, indicating specificity of tamoxifen-PSACreERT2 mediated deletion of the Ezh2 set domain. (C) Principle component analysis (PCA) following chemical and genetic inhibition of Ezh2 catalytic function results in significant changes in gene expression. 2 Fig. S2. (A) A 29-gene signature derived from Fig. 1C demonstrates complete independence from a previously published polycomb repression signature. (B) Our 29 gene signature demonstrates significant correlation with a previously published polycomb repression signature in 2 independent human PCa gene expression datasets. (C) EZH2 activity is not determined by EZH2 mRNA expression. 3 Fig. S3. A 29-gene signature derived from Fig 1C was used to generate signature scores for each patient within four independent human prostate cancer RNA-seq datasets. Patients were ranked highest score to lowest score and subject to quartile separation. First (blue) and fourth (red) quartiles were analyzed by supervised clustering to demonstrate expression differences within patients with most lowest EZH2 activity and most highest EZH2 activity. 4 Fig. S4. Genes representing IFN signaling (STAT1, IRF9), Th1 chemokines (CXCL10, CXCL11), and MHC Class I molecules (B2M, HLA-A) were shown to be enriched in PCa patients with low EZH2 activity. 5 Fig. S5. Treatment of 22Rv1 human 2D cell lines with the demonstrated conditions for 96 hours show that EZH2 inhibition increases expression of dsRNA (green = dsRNA, blue = nuclei). -

Supplementary Table 1: Differentially Methylated Genes and Functions of the Genes Before/After Treatment with A) Doxorubicin and B) FUMI and in C) Responders Vs

Supplementary Table 1: Differentially methylated genes and functions of the genes before/after treatment with a) doxorubicin and b) FUMI and in c) responders vs. non- responders for doxorubicin and d) FUMI Differentially methylated genes before/after treatment a. Doxo GENE FUNCTION CCL5, CCL8, CCL15, CCL21, CCR1, CD33, IL5, immunoregulatory and inflammatory processes IL8, IL24, IL26, TNFSF11 CCNA1, CCND2, CDKN2A cell cycle regulators ESR1, FGF2, FGF14, FGF18 growth factors WT1, RASSF5, RASSF6 tumor suppressor b. FUMI GENE FUNCTION CCL7, CCL15, CD28, CD33, CD40, CD69, TNFSF18 immunoregulatory and inflammatory processes CCND2, CDKN2A cell cycle regulators IGF2BP1, IGFBP3 growth factors HOXB4, HOXB6, HOXC8 regulation of cell transcription WT1, RASSF6 tumor suppressor Differentially methylated genes in responders vs. non-responders c. Doxo GENE FUNCTION CBR1, CCL4, CCL8, CCR1, CCR7, CD1A, CD1B, immunoregulatory and inflammatory processes CD1D, CD1E, CD33, CD40, IL5, IL8, IL20, IL22, TLR4 CCNA1, CCND2, CDKN2A cell cycle regulators ESR2, ERBB3, FGF11, FGF12, FGF14, FGF17 growth factors WNT4, WNT16, WNT10A implicated in oncogenesis TNFSF12, TNFSF15 apoptosis FOXL1, FOXL2, FOSL1,HOXA2, HOXA7, HOXA11, HOXA13, HOXB4, HOXB6, HOXB8, HOXB9, HOXC8, regulation of cell transcription HOXD8, HOXD9, HOXD11 GSTP1, MGMT DNA repair APC, WT1 tumor suppressor d. FUMI GENE FUNCTION CCL1, CCL3, CCL5,CCL14, CD1B, CD33, CD40, CD69, immunoregulatory and inflammatory IL20, IL32 processes CCNA1, CCND2, CDKN2A cell cycle regulators IGF2BP1, IGFBP3, IGFBP7, EGFR, ESR2,RARB2 -

Discovery of Deoxyceramides and Diacylglycerols As Cd1b Scaffold Lipids Among Diverse Groove-Blocking Lipids of the Human CD1 System

Discovery of deoxyceramides and diacylglycerols as CD1b scaffold lipids among diverse groove-blocking lipids of the human CD1 system Shouxiong Huanga, Tan-Yun Chenga, David C. Younga, Emilie Layrea, Cressida A. Madigana, John Shiresb, Vincenzo Cerundoloc, John D. Altmanb, and D. Branch Moodya,1 aDepartment of Medicine, Division of Rheumatology, Immunology and Allergy, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115; bEmory Vaccine Center, Emory School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30322; and cMedical Research Council Human Immunology Unit, Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford OX3 9DS, United Kingdom Edited* by Peter Cresswell, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, and approved October 17, 2011 (received for review August 10, 2011) Unlike the dominant role of one class II invariant chain peptide (CLIP) environment (7, 8). The differing pH requirements for antigen in blocking MHC class II, comparative lipidomics analysis shows that loading, combined with enrichment of endogenous lipids in the human cluster of differentiation (CD) proteins CD1a, CD1b, CD1c, secretory pathway and exogenous lipids endosomes, are coalescing and CD1d bind lipids corresponding to hundreds of diverse accurate into a two-step model of lipid antigen presentation. First, newly mass retention time values. Although most ions were observed in translated CD1 proteins, aided by the microsomal triglyceride association with several CD1 proteins, ligands binding selectively to transport protein (MTP) (9), -

Mechanisms and Consequences of Antigen Presentation By

Series: The Biology of Antigen Presentation Feature Review Mechanisms and Consequences of Antigen Presentation by CD1 1, 1 1,2 Luc Van Kaer, * Lan Wu, and Sebastian Joyce The CD1 proteins are a family of non-polymorphic and MHC class I-related Trends molecules that present lipid antigens to subsets of T lymphocytes with innate- or The CD1–lipid presentation system adaptive-like immune functions. Recent studies have provided new insight into allows the immune system to sense alterations in lipid homeostasis, and the identity of immunogenic CD1 antigens and the mechanisms that control the complements the classical MHC–pep- generation and loading of these antigens onto CD1 molecules. Furthermore, tide presentation system. There are substantial progress has been made in identifying CD1-restricted T cells and remarkable similarities and surprising differences in the way that TCRs decoding the diverse immunological functions of distinct CD1-restricted T cell engage CD1–lipid versus MHC–pep- subsets. These findings shed new light on the contributions of the CD1 antigen- tide complexes. presentation pathway to normal health and to a diverse array of pathologies, and Group 1 CD1 proteins (CD1a–c) pre- provide a new impetus for exploiting this fascinating recognition system for the sent a variety of endogenous, myco- development of vaccines and immunotherapies. bacterial, and potentially other bacterial lipids to T cells. CD1b-restricted T cells include subsets expressing germline- Antigen-Presentation Systems encoded TCRs. Products encoded by the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) region of the vertebrate Group 2 CD1 proteins (CD1d) present genome bind peptide fragments from pathogens and display them at the surface of antigen- diverse endogenous and exogenous presenting cells (APCs) for appraisal by T lymphocytes [1]. -

Human CD Marker Chart Reviewed by HLDA1 Bdbiosciences.Com/Cdmarkers

BD Biosciences Human CD Marker Chart Reviewed by HLDA1 bdbiosciences.com/cdmarkers 23-12399-01 CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD1a R4, T6, Leu6, HTA1 b-2-Microglobulin, CD74 + + + – + – – – CD93 C1QR1,C1qRP, MXRA4, C1qR(P), Dj737e23.1, GR11 – – – – – + + – – + – CD220 Insulin receptor (INSR), IR Insulin, IGF-2 + + + + + + + + + Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R), IGF-1R, type I IGF receptor (IGF-IR), CD1b R1, T6m Leu6 b-2-Microglobulin + + + – + – – – CD94 KLRD1, Kp43 HLA class I, NKG2-A, p39 + – + – – – – – – CD221 Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-I), IGF-II, Insulin JTK13 + + + + + + + + + CD1c M241, R7, T6, Leu6, BDCA1 b-2-Microglobulin + + + – + – – – CD178, FASLG, APO-1, FAS, TNFRSF6, CD95L, APT1LG1, APT1, FAS1, FASTM, CD95 CD178 (Fas ligand) + + + + + – – IGF-II, TGF-b latency-associated peptide (LAP), Proliferin, Prorenin, Plasminogen, ALPS1A, TNFSF6, FASL Cation-independent mannose-6-phosphate receptor (M6P-R, CIM6PR, CIMPR, CI- CD1d R3G1, R3 b-2-Microglobulin, MHC II CD222 Leukemia -

Cells and Marginal Zone B Cells CD1.1 Expression by Mouse Antigen-Presenting

CD1.1 Expression by Mouse Antigen-Presenting Cells and Marginal Zone B Cells Jessica H. Roark, Se-Ho Park, Jayanthi Jayawardena, Uma Kavita, Michele Shannon and Albert Bendelac This information is current as of September 29, 2021. J Immunol 1998; 160:3121-3127; ; http://www.jimmunol.org/content/160/7/3121 References This article cites 48 articles, 26 of which you can access for free at: Downloaded from http://www.jimmunol.org/content/160/7/3121.full#ref-list-1 Why The JI? Submit online. http://www.jimmunol.org/ • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: by guest on September 29, 2021 http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 1998 by The American Association of Immunologists All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. CD1.1 Expression by Mouse Antigen-Presenting Cells and Marginal Zone B Cells1 Jessica H. Roark, Se-Ho Park, Jayanthi Jayawardena, Uma Kavita, Michele Shannon, and Albert Bendelac2 Mouse CD1.1 is an MHC class I-like, non-MHC-encoded, surface glycoprotein that can be recognized by T cells, in particular NK1.11 T cells, a subset of ab T cells with semiinvariant TCRs that promptly releases potent cytokines such as IL-4 and IFN-g upon stimulation. -

Intracellular Pathways of Cd1 Antigen Presentation

REVIEWS INTRACELLULAR PATHWAYS OF CD1 ANTIGEN PRESENTATION D. Branch Moody* and Steven A. Porcelli‡ Each of the human CD1 proteins takes a different route through secretory and endocytic compartments before finally arriving at the cell surface, where these proteins present glycolipid antigens to T cells. Recent studies have shown that adaptor-protein complexes and CD1-associated chaperones control not only CD1 trafficking, but also the development and activation of CD1-restricted T cells. This indicates that CD1 proteins, similar to MHC class I and II molecules, selectively acquire certain antigens in distinct cellular subcompartments. Here, we summarize evidence supporting the hypothesis that CD1 proteins use separate, but parallel, pathways to survey endosomal compartments differentially for lipid antigens. For many years, it was thought that peptides were the phosphatidylinositols, sphingolipids and polyiso- only structurally varied targets of T-cell responses. The prenoid lipids10–15. These known antigens, together discovery of CD1-dependent antigen-presentation with diffferentially glycosylated derivatives of these pathways provided a mechanism by which T cells can lipids that might function as antigens, form a poten- specifically recognize an array of lipids and glycolipids tially large pool of structures that could be recognized that comprise the membranes of mammalian cells and by CD1-restricted T cells. Although certain CD1D- microbial pathogens1. Mouse CD1d, and guinea-pig restricted natural killer T (NKT) cells use TCRs of lim- CD1b and CD1c, as well as four of the five human ited diversity, the available evidence indicates that the CD1 proteins (CD1A, CD1B, CD1C and CD1D), have CD1-restricted T-cell repertoire also includes T cells been shown to bind and present lipid antigens to with substantial TCR diversity16–20. -

Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells As a Therapeutic Target for Cancer

cells Review Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells as a Therapeutic Target for Cancer 1, 2,3, , 1,3, Andrew M. K. Law * , Fatima Valdes-Mora * y and David Gallego-Ortega * 1 Tumour Development Group, The Kinghorn Cancer Centre, Garvan Institute of Medical Research, Sydney, NSW 2010, Australia 2 Histone Variants Group, Garvan Institute of Medical Research, Sydney, NSW 2010, Australia 3 St. Vincent’s Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine, University of New South Wales Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] (A.M.K.L.); [email protected] (F.V.-M.); [email protected] (D.G.-O.); Tel.: +61-(0)2-9355-5894 (A.M.K.L); +61-(0)2-9385-0143 (F.V.-M); +61-(0)2-9355-5776 (D.G.-O) Current: Cancer Epigenetic Biology and Therapeutics Lab, Children’s Cancer Institute, Sydney, y NSW 2052, Australia. Received: 4 February 2020; Accepted: 24 February 2020; Published: 27 February 2020 Abstract: The emergence of immunotherapy has been an astounding breakthrough in cancer treatments. In particular, immune checkpoint inhibitors, targeting PD-1 and CTLA-4, have shown remarkable therapeutic outcomes. However, response rates from immunotherapy have been reported to be varied, with some having pronounced success and others with minimal to no clinical benefit. An important aspect associated with this discrepancy in patient response is the immune-suppressive effects elicited by the tumour microenvironment (TME). Immune suppression plays a pivotal role in regulating cancer progression, metastasis, and reducing immunotherapy success. Most notably, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC), a heterogeneous population of immature myeloid cells, have potent mechanisms to inhibit T-cell and NK-cell activity to promote tumour growth, development of the pre-metastatic niche, and contribute to resistance to immunotherapy.