Kirtsaeng V. John Wiley & Sons, Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Netherlands: Paving the Way for Open Access

The Netherlands: paving the way for open access The negotiations: ‘Big deals’ as lever 15 important results: The road to open access 4 factors of success: ‘The Dutch Approach’ Open access: How does open access publishing work? The future: Creating momentum Table of contents Introduction 3 Paving the way for open access 4 ‘Big deals’ as lever 6 The road to open access 8 ‘The Dutch Approach’ 12 How does open access publishing work? 16 Creating momentum 19 2 Introduction Dear reader, The Netherlands is undergoing rapid growth in the field of open access, which is being recognised across the globe. This rapid growth is the result of a unique approach, inspired and supported by other national and international organisations. In October 2014, I stated that although the Netherlands is not alone, I am confident our country is leading the way towards open access. It is up to you to be the judge of this, as you read through this magazine. Dutch universities have together taken great steps towards enabling open access to scientific articles for everyone. Contracts with large publishing houses have been concluded whereby the articles of our researchers can now be openly accessed online, at no extra cost. More and more publishers are willing to make the switch to open access publishing. Some publishers want to make the switch right away, while others are willing to do so in smaller steps. Our neighbouring countries are bene fiting from the road that we have taken in the Netherlands. It helps them to make progress in the field of open access and, conversely, it helps the Netherlands to continue to develop. -

Physical Sciences, Life Sciences & Social Science

WILEY INDIA ADAPTATION We are adapting to your needs... 2020 To place an order, please contact following. Physical Sciences, RESELLER / IMPORTS / ONLINE SALES Kamal Chandel Email: [email protected] Life Sciences & ACADEMIC & TEST PREP CHANNEL NORTH SOUTH Social Science Jitender Kumar Ailawadi Andhra Pradesh / Telangana / Kerala Tamil Nadu Karnataka Email: [email protected] Mansoor Baig Murugan M. Surendra K. Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] WEST EAST Swapnil Koranne Vilas Ichalkaranje Bihar / Jharkhand West Bengal / Odisha / North East Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Niraj Kumar Sinha Kiran Powrely Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Wiley India Pvt. Ltd. HEAD OFFICE: 1402, 14th Floor World Trade Tower, Plot No. C-1, Sector-16, Noida 201301 INDIA Tel: 0120-6291100 Email: [email protected] BANGALORE: 14, Dr. Raj Kumar Road, 4th N Block, Rajaji Nagar, Bangalore - 560010 Tel: 080-42896464 Telefax: 080-23124319 Email: [email protected] MUMBAI: Wework Vijay Diamond No. A3 & B2, Cross Road B, Marol, Industrial Area, Mumbai, Maharashtra 400093 Email: [email protected] Electrical, Electronics wileyindia.com | wileyindia.com/e-books | wileynxt.com & Instrumentation /wileyindia /wileyindiapl /WileyIndiaPL Engineering Books are available at Exclusive Wiley Brand Store @ www.amazon.in/wiley www.wileyindia.com WILEY INDIA ADAPTATIONS We are adapting to your needs... Catalog 2020 www.wileyindia.com CONTENTS Learn More. Learn the New Way Wiley eTextBooks New Releases CHEMISTRY -

WILEY V. AUSTIN – BACKGROUNDER Executive Summary the Goldwater Institute Has Been on the Cutting Edge of Using Anti-Subsidy Pr

WILEY v. AUSTIN – BACKGROUNDER Executive Summary The Goldwater Institute has been on the cutting edge of using anti-subsidy provisions of state constitutions to eliminate an egregious taxpayer abuse called “release time.” Release time is a practice where government employees are “released” from the jobs they were hired to perform to work exclusively for government unions – all while receiving taxpayer funded salaries and benefits. While on release time, government workers are paid to increase union membership, engage in political activities, lobby the government, file grievances against their employer, and negotiate for higher wages and benefits, among other activities. Release time exists at the federal, state, and local level. The Institute’s litigation successfully ended the practice of release time in Arizona. But the practice of release time is prevalent in many other states, including Texas. Release time exists throughout Texas, and is particularly pervasive in the City of Austin, among three separate union groups: police, fire, and EMS. This case is a taxpayer challenge to the collective bargaining agreement between the City of Austin (“City”) and the Austin Firefighters’ Association (“AFA”). Plaintiff taxpayers argue that release time constitutes an unlawful subsidy to a private entity under the Texas Constitution. The primary goals in this litigation are to eliminate release time and build favorable anti- subsidy case law in Texas that can be used to address abuse of taxpayer funds and other forms of government cronyism. Background Imagine if your city council contacted a local Walmart and offered them full-time city employees to use however Walmart wished – as checkout clerks, greeters, stockers. -

Meeting in the Middle- Adapting Your Style to Accommodate Others

Meeting in the Middle- Adapting your Style to Accommodate Others Presenter: Alyssa Johnston, Iowa Corn Growers Association Objectives • Background and history of personality indicators and assessments. • Learn DiSC styles and how to best work with each. GOAL: Walk away with a better understanding of yourself and learn skills to effectively communication with others. What questions do you have? What do you want to make sure we cover? First, Plan A Vacation! • Activity 1 • Take 5 to 7 minutes to write down a plan to visit your favorite vacation destination. • Where • What • When • Who Different Assessment Tools WIIFM • Provide for better understanding of ourselves. • Provide for better understanding of others. • Improve communication and interaction. • Work better as a team. What Is Your Style? • Activity 2 • Let’s move! How You See Yourself Fast-Paced & Outspoken Cautious & Reflective 8 Copyright ©2018 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. How You See Yourself Questioning Accepting & Skeptical & Warm 9 Copyright ©2018 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. How You See Yourself Fast-Paced & Outspoken Questioning Accepting & Skeptical & Warm Cautious & Reflective 10 Copyright ©2018 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. How You See Yourself Fast-Paced & Outspoken Questioning Accepting & Skeptical & Warm Cautious & Reflective 11 Copyright ©2018 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. 12 Copyright ©2018 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. “D” Style • DOMINANCE – Priorities: getting immediate results, taking action, challenging self and others – Motivated by: power and authority, competition, winning, success – Fears: loss of control, vulnerability – You will notice: self-confidence, directness, forcefulness – Limitations: impatience, insensitivity, lack of concern for others 13 Copyright ©2018 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. -

Toward a Developmental Science of Politics

Toward a Developmental Science of Politics Meagan M. Patterson, Rebecca S. Bigler, Erin Pahlke, Christia Spears Brown, Amy Roberson Hayes, M. Chantal Ramirez, and Andrew Nelson Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development Lynn S. Liben, Editor VOL. 84 | NO. 3 | 2019 | SERIAL NO. 334 Society for Research in Child Development INFORMATION FOR AUTHORS The Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development is a quarterly journal which publishes conceptually rich and empirically distinguished work in support of the SRCD mission—advancing developmental science and promoting its use to improve human lives. To be accepted for publication, manuscripts must be judged to serve one or more core goals of SRCD’s Strategic Plan, which include (1) the advancement of cutting-edge and integrative developmental science research; (2) the fostering of racial, cultural, economic, national, and contextual diversity in developmental science; and (3) the application of developmental science to policies and practices that improve human well-being. As explained more fully in the document Editorial Statement (https://www.srcd.org/ publications/monographs/monographs-editorial-statement), such goals may be achieved in varied ways. For example, a monograph might integrate results across waves of a longitudinal study; consolidate and interpret research literatures through meta-analyses; examine developmental phenomena across diverse and intersecting ethnic, geographic, economic, political, or historical contexts; describe and demonstrate new developmental tools for data acquisition, visualization, analysis, sharing, or replication; or report work contributing to conceptualizing, designing, implementing, and evaluating national and global programs and policies (e.g., related to parenting, education, or health). The journal has an extensive reach via direct distribution to 5,000+ SRCD members and to readers via access provided through 12,000+ institutions worldwide. -

Cloud Computing Bible Is a Wide-Ranging and Complete Reference

A thorough, down-to-earth look Barrie Sosinsky Cloud Computing Barrie Sosinsky is a veteran computer book writer at cloud computing specializing in network systems, databases, design, development, The chance to lower IT costs makes cloud computing a and testing. Among his 35 technical books have been Wiley’s Networking hot topic, and it’s getting hotter all the time. If you want Bible and many others on operating a terra firma take on everything you should know about systems, Web topics, storage, and the cloud, this book is it. Starting with a clear definition of application software. He has written nearly 500 articles for computer what cloud computing is, why it is, and its pros and cons, magazines and Web sites. Cloud Cloud Computing Bible is a wide-ranging and complete reference. You’ll get thoroughly up to speed on cloud platforms, infrastructure, services and applications, security, and much more. Computing • Learn what cloud computing is and what it is not • Assess the value of cloud computing, including licensing models, ROI, and more • Understand abstraction, partitioning, virtualization, capacity planning, and various programming solutions • See how to use Google®, Amazon®, and Microsoft® Web services effectively ® ™ • Explore cloud communication methods — IM, Twitter , Google Buzz , Explore the cloud with Facebook®, and others • Discover how cloud services are changing mobile phones — and vice versa this complete guide Understand all platforms and technologies www.wiley.com/compbooks Shelving Category: Use Google, Amazon, or -

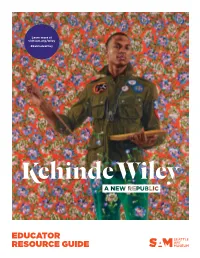

Educator Resource Guide Overview

Learn more at visitsam.org/wiley #KehindeWiley EDUCATOR RESOURCE GUIDE OVERVIEW ABOUT THE EXHIBITION Organized by the Brooklyn Museum, this exhibition brings together over 50 of Kehinde Wiley’s portraits in large-scale paintings, bronze sculptures, and stained glass from the last fifteen years. Wiley is one of the leading contemporary American artists, reworking the grand portraiture traditions of Western culture. Wiley began his first series of portraits in the early 2000s during a residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem. He set out to recast young African American men from the neighborhood in the style and manner of traditional history painting. Since then he has also painted pop culture stars, although his primary focus remains ordinary people in their own clothes and style. Trained at Yale in the 1990s, Wiley brings a strong understanding of traditional painting techniques to an interest in contemporary issues of identity and power. Wiley’s portraits recreate the poses of European aristocrats, contrasting elaborate and ornate backgrounds with contemporary subjects in their own clothes. These choices draw attention to the lack of images of people of color in historical and contemporary works. SAM’s Educator Resource Guide highlights three works from the exhibition and explores ideas about how these works examine personal and cultural identities. ABOUT THE ARTIST “Going to the museums [in Los Angeles] and increasingly throughout the world as an adult, you start to realize that those images of people of color just don’t exist. And there’s something to be said about simply being visible.” Kehinde Wiley, CBC radio interview for Q, February 20, 2014 Born in Los Angeles in 1977, Kehinde Wiley began attending art classes on the weekend with his brother when he was eleven. -

Alternative Textbooks Publishers

ALTERNATIVE TEXT PUBLISHERS TUTORING SERVICES 2071 CEDAR HALL ALTERNATIVE TEXT PUBLISHERS Below is a list of all the publishers we work with to provide alternative text files. Aaronco Pet Products, Inc. Iowa State: Extension and Outreach Abrams Publishing Jones & Bartlett Learning ACR Publications KendallHunt Publishing Alpine Publisher Kogan Page American Health Information Management Associations Labyrinth Learning American Hotels and Lodging Legal Books Distributing American Technical Publishers Lippincott Williams and Wilkins American Welding Society Longleaf Services AOTA Press Lynne Rienner Publishers Apress Macmillan Higher Education Associated Press Manning Publications ATI Nursing Education McGraw-Hill Education American Water Works Association Mike Holt Enterprises Baker Publishing Group Morton Publishing Company Barron's Mosby Bedford/St. Martin's Murach Books Bison Books NAEYC Blackwell Books NASW Press National Board for Certification in Bloomsbury Publishing Dental Laboratory Technology (NBC) National Restaurant Association/ Blue Book, The ServSafe Blue Door Publishing Office of Water Programs BookLand Press Openstax Broadview Press O'Reilly Media Building Performance Institute, Inc. Oxford University Press BVT Publishing Paradigm Publishing Cadquest Pearson Custom Editions ALTERNATIVE TEXT PUBLISHERS Cambridge University Press Pearson Education CE Publishing Peguin Books Cengage Learning Pennwell Books Charles C. Thomas, Publisher Picador Charles Thomas Publisher Pioneer Drama Cheng & Tsui PlanningShop Chicago Distribution -

Fulltext: Full Text of 'Scholarly' Articles Across Many Data Sources

Package ‘fulltext’ June 12, 2021 Title Full Text of 'Scholarly' Articles Across Many Data Sources Description Provides a single interface to many sources of full text 'scholarly' data, including 'Biomed Central', Public Library of Science, 'Pubmed Central', 'eLife', 'F1000Research', 'PeerJ', 'Pensoft', 'Hindawi', 'arXiv' 'preprints', and more. Functionality included for searching for articles, downloading full or partial text, downloading supplementary materials, converting to various data formats. Version 2.0 License MIT + file LICENSE URL https://docs.ropensci.org/fulltext/ (website) https://github.com/ropensci/fulltext/ (devel) https://books.ropensci.org/fulltext/ (user manual) BugReports https://github.com/ropensci/fulltext/issues LazyLoad yes Encoding UTF-8 Language en-US Depends R (>= 2.10) Imports crul (>= 0.7.0), magrittr, xml2 (>= 1.1.1), jsonlite, rplos (>= 0.8.0), rcrossref (>= 0.8.0), microdemic (>= 0.2.0), aRxiv, rentrez (>= 1.1.0), data.table, hoardr (>= 0.5.0), pdftools, storr, tibble, digest, fauxpas Suggests roxygen2 (>= 7.1.0), testthat, pubchunks, vcr RoxygenNote 7.1.1 X-schema.org-applicationCategory Literature X-schema.org-keywords text-mining, literature, pdf, xml, publications, citations, full-text, TDM X-schema.org-isPartOf https://ropensci.org NeedsCompilation no 1 2 fulltext-package Author Scott Chamberlain [aut, cre] (<https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1444-9135>), rOpenSci [fnd] (https://ropensci.org/) Maintainer Scott Chamberlain <[email protected]> Repository CRAN Date/Publication 2021-06-12 04:10:07 UTC R topics documented: fulltext-package . .2 as.ft_data . .5 as_ftdmurl . .7 cache . .8 cache_file_info . .9 ftdoi_cache . 10 ftd_doi . 11 ftd_fetch_patterns . 14 ftxt_cache . 14 ft_abstract . 15 ft_browse . 18 ft_collect . 18 ft_cr_links . 19 ft_extract . -

Extended Essay Cover Baccalaureate

IF) International Extended essay cover Baccalaureate Candidates must complete this page and then give this cover and their final version of the extended essay to their supervisor. ~ . - · ~ Candidate session number Candidate name I \___..;I School number I , ~ School name j Examination session (May or November) .I Year I PlAY r 2o /2 Diploma Programme subject in which this extended essay is registered·l,[ i<..,"f/!J'L (<. g. HI!A /"1(.,' VLA r ,~ L (For an extended essay in the area of languages, state the language and whether it is group 1 or group 2.) Title of the extended essay: rHE (OF[Yd'AT£ Ci iL-7CiJ Alvj) LlA!>J:!.\If;p !- \'! t 6 1 /ItA AI'l l ! f "Lk t.. \ iitf/ I C.. !7!. Aro /P, ~ ll n 1T TI £, (( t/Cl'!i n ,TtL[ '< Candidate's declaration This declaration must be signed by the candidate; otherwise a grade may not be issued. The extended essay I am submitting is my own work (apart from guidance allowed by the International Baccalaureate). I have acknowledged each use of the words, graphics or ideas of another person, whether written, oral or visual. I am aware that the word limit for all extended essays is 4000 words and that examiners are not required to read beyond this limit. This is the final version of my extended essay. Candidate's signature: International Baccalaureate, Peterson House, ----------Malthous.e Avenue C;m!iff G:=!IP. r.r~rrliff W:=!IP.s r.F?~ RGI l JnitP.rl Kinndnm __________ Supervisor's report and declaration The superv1sor must complete th1s report, s1gn the declaration and then give the final vers1on of the extended essay. -

JOHN WILEY & SONS, Inc., 440-4Th Ave., New York 16, N. Y

ELEMENTARY TOPOLOGY By DICK WICK HALL and GUILFORD L. SPENCER II, both of the University of Maryland. The first elementary text on general point set topology. A wide variety of proofs is presented and over 400 problems are included. 1955• Approx. 320 pages. Prob. $7.00. ADVANCED CALCULUS: An Introduction to Classical Analysis By LOUIS BRAND, University of Cincinnati. A systematic treatment of classical analysis—from the development of the real number system to the function of real and complex variables. 29.5.5. 574 pages. $8.50. STOCHASTIC MODELS FOR LEARNING* By ROBERT R. BUSH and FREDERICK MOSTELLER, both of Harvard University. The first systematic attempt to present a probabilistic analysis of the data obtained in learning experiments through the use of stochastic processes. 1955. 365 pages. $9.00. AN INTRODUCTION TO DEDUCTIVE LOGIC By HUGUES LEBLANC, Bryn Mawr College. A readable exposition of the essentials of modern logic, with an equal balance between the mathematical and philosophical approaches. 1955, 244 pages. $4.75. ADVANCED MATHEMATICS FOR ENGINEERS, Third Edition By H. W. REDDICK, formerly of New York University; and F. H. MILLER, The Cooper Union School of Engineering. Third edition revised by F. H. Miller. Pinpoints abstract mathematical concepts and gives concrete examples of the best way to use higher mathematics in the four main engineering fields. 1955. 548 pages. $6.50. THE ELEMENTS OF PROBABILITY THEORY AND SOME OF ITS APPLICATIONS* By HARALD CRAMER, University of Stockholm. A compact discussion of the mathe matical theory emphasizing random variables and probability distribution—plus a fruit ful survey of important applications. -

Wal-Mart, Leisure, and Culture By

Wal-Mart, Leisure, and Culture By: Art Carden and Charles Courtemanche Carden, A. and Courtemanche, C. “Wal-Mart, Leisure, and Culture”. Contemporary Economic Policy, 2009, 27(4), 450-461. DOI: 10.1111/j.1465-7287.2009.00167.x ***Reprinted with permission. No further reproduction is authorized without written permission from Wiley-Blackwell. This version of the document is not the version of record. Figures and/or pictures may be missing from this format of the document. *** The definitive version is available at www3.interscience.wiley.com. Abstract: This essay contributes to the debate about the alleged spillover effects associated with Wal- Mart’s growth. Combining county-level data on Wal-Mart entry and location from 1985 through 1998 with individual-level data on leisure activities, we estimate a positive relationship between Wal-Mart penetration and participation in activities involving inputs that can be bought at Wal- Mart. The relationship between Wal-Mart penetration and activities that do not involve inputs that can be bought at Wal-Mart is negative in most cases but may be positive or zero for “cultural” activities such as attending classical music concerts and visiting art galleries. The evidence is consistent with the thesis that deeper Wal-Mart penetration expands consumption possibilities. (JELA13, D00, C12, Z11, Z13) Keywords: economics | Wal-Mart | leisure activities | consumption | Wal-Mart growth | cultural activities Article: I. INTRODUCTION Do Wal-Mart’s “Every Day Low Prices” cause people to ignore T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land in favor of television’s “vast wasteland” or is Wal-Mart’s effect on leisure and cultural activities more benign? Wal-Mart is both a cause and a consequence of economic and social change.