The Origin of the Lathes of East Kent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northbourne. Finglesham

• 402 NORTHBOURNE. XENT. [KELLY'S NORTHBOURNE, so named from its situation at 'the of Betteshanger. The principal landowners are Sir WaIter souree of a small brook running to "Sandwich, is a parish, in Charles James bart. Frederick Morrice esq. Henry Hannam the Eastern division of the county, Cornilo hundred, lathe esq. and -the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, Admiral Rice, of St. Augustine, union of Eastry, Deal county court and and the EaTl of Guilford. The soil is loamy; subsoil, chalk. police district, Sandwich rural deanery, diocese and archdea Thechief crops are wheat, barley and oats. Theareais 3,628 conry of Canterbury, 3 miles south-west from Deal and 4 acres; t"ateable value £7,168 ; and the population in I881 south from Sandwich. Thechurch of St. Augustine is a eru was 947. ciform building of rough flint and brick, in the Norman and ASHLEY,4 miles south-westhasa Methodistchapel; FINGLES Early English styles, often intermixed in a curious manner, HAM, one mile and a half north (here is a Methodist chapel) ; consisting of chancel, nave, transepts and a eentral tower, LITTLE BETTESHANGER, I mile west; and MARLEY, I mile containing 5 bells: over a vault in the south transept is a north, are hamlets in this parish. Inarble monument to Sir Edwin Sandys and his family, who NAPCHESTER, MINKER and WEST STUDDAL are in a de are buried here; upon it are recuInbent effigies of a knight tached portion of Northbourne parish. in armour and his lady; and above the pendiment and TICKENHURST is a detached part of the parish, in Eastry around it are several armorial shields; there is a costly hundred and union, I mile north-west from Eastry, with reredos and a beautiful stained window, given by Sarah, I45 acres and 30 inhabitants. -

NAME ADDRESS EMPTY START DATE Coral Estates Ltd 97

NAME ADDRESS EMPTY START DATE Coral Estates Ltd 97, Sandgate Road, Folkestone, Kent, CT20 2BQ EPRN 01/04/2008 Our Lady Of Fidelity Folkestone Trust St Marys Westbrook, Ravenlea Road, Folkestone, Kent, CT20 2JU EPRN 08/12/2008 Bede Property Investments Ltd Unit K, 9a, Lympne Industrial Park, Lympne, Hythe, Kent, CT21 4LR RV under 2600 01/04/2010 Industrial Investment Partnership Unit K, 9a, Lympne Industrial Park, Lympne, Hythe, Kent, CT21 4LR RV under 2600 01/04/2010 Irere Eagle 1 Ltd & Irere Eagle 2 Ltd Unit K, 9a, Lympne Industrial Park, Lympne, Hythe, Kent, CT21 4LR RV under 2600 01/04/2010 Schroder Exempt Prop Unit Trust Unit K, 9a, Lympne Industrial Park, Lympne, Hythe, Kent, CT21 4LR RV under 2600 01/04/2010 Schroder Exempt Prop Unit Trust Unit K, 9a, Lympne Industrial Park, Lympne, Hythe, Kent, CT21 4LR RV under 2600 01/04/2010 Dollond & Aitchison Limited 78a, Sandgate Road, Folkestone, Kent, CT20 2AA EPRN 01/04/2011 East Kent Housing 33, The Green, Burmarsh, Romney Marsh, Kent, TN29 0JL EPRN 01/04/2011 Eat.The Real Food Co. Ltd 12, Stop 24 Services & Port Early Arrivals, Junction 11 M20 Stanford Intersection, Stanford, Ashford, Kent, CT21 4BL EPRN 01/04/2011 Glengate (Folkestone) Ltd 1st Flr, 81-83, Sandgate Road, Folkestone, Kent, CT20 2AF EPRN 01/04/2011 Haag Juristen College (Cyprus Ltd) Ground Floor 80, Sidney Street, Folkestone, Kent, CT19 6HA EPRN 01/04/2011 Hsbc Bank Plc 353, Cheriton Road, Folkestone, Kent, CT19 4BP EPRN 01/04/2011 Irere Eagle 1 Ltd & Irere Eagle 2 Ltd Unit 7 2nd Floor, Dyna House, Lympne Industrial Park, -

Notes on the Probable Course of the Roman Road from Lympne to Dover

Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 62 1949 NOTES ON THE PROBABLE COURSE OF THE ROMAN ROAD FROM LYMPNE TO DOVER By IVAN D. MARGARY, F.S.A. THE existence of a Roman road connecting Lympne with. Dover is attested by its actual appearance upon the diagrammatic map known as the Peutinger Table. No traces of the road had, however, been identified, and the growth of Folkestone and its outskirts has now put much of the probable route beyond direct investigation. Some notes were put forward by the late S. E. Winbolt in his book Roman Folkestone (Methuen, 1925) as a tentative approach to the subject, and it was with a view to testing these on the ground that the present investigation was made. There is general agreement that the existing road along the old cliffs at Lympne represents the Roman road. East of Shipway Cross it bends a good deal and is probably an old ridgeway track rather than an engineered road, but there seems no reason to disregard it as a part of the route on that account. We thus arrive at the crossing of the Brockhill Stream, just at the western entry to Hythe, and it seems clear that the trackway is directly continued by an old lane, now in part only a footpath, straight up the hill north-eastwards to Saltwood, making no doubt for the hills inland. Consideration of the eastward course of a Roman road from this point is very largely determined by the topography, which here shows marked features some of which would entirely preclude the making of a direct road. -

Evn June July 2020 Print 14

June/ July 2020 THANK YOU NHS and Police Forces, Fire Services, our armed forces, key workers, utility workers, the food chain, Post Office staff, chemists, carers, essential shops & garages, teachers, council staff, delivery drivers, the transport networks, vets, volunteers, helpers, maintenance/repair businesses, good neighbours, charity workers, Captain Tom & everyone else playing a part in helping overcome this pandemic. Not forgetting all the residents and businesses of Eastry who have done their best to help others during this time of crisis. Well done! 2 Village Contacts Ambulance, Fire, Police 999 Gas Emergency 0800 111999 Police Community Support 101 Highways Fault Reporting & non-emergency Police 03000 418181 PCSO - Richard Bradley UK Power Network 105 [email protected] C of E Primary School 611360 Head Teacher: Community Warden – Peter Gill Associate Head: Mrs.S.Moss 07703 454190 [email protected] PTA Treasurer: Justine Crane Neighbourhood Watch Parish Council Sheila Smith 611580 www.eastrypc.co.uk www.facebook.com/EastryPC Doctors Surgery 619790 Chairman: Nick Kenton The Market Place, Sandwich Vice-Chairman: Mark Jones Emergency out of hours 111 Clerk to Council Sarah Wells 614320 ([email protected]) Eastry Ravens F.C. – Steve Booth 3 Gore Terrace, Gore Road, 07864 925289 email:[email protected] Eastry, Sandwich, Kent CT13 0LS BICKERS Your local Shop, Newsagent and Post Office Your first stop for newspapers & magazines Wide range of confectionary Good selection of greeting cards & stationery Milk & essential -

IYW\I 13Curfv~O-Rte/ VVS CAMRA Pub-Oftfte; Y~ 2004- the Village Pub in Dover

.,/ Great Ales from Kent's best micros and others .,/ Always a cask mild ft~."" ~ ~~ .,/ Quality selection of wines from Europe and New World ~~ ~~ .,/ Fresh home-cooked food 6 days a week «...~ C'~ q~ .,/ Provision for both smokers and anti·smokers! .,/ NO pool table, jukebox, fruit machines or other nonsense to distract you from the food and drink! 40p a pint off real ales and Kentish Cider for CAMRA members from 5pm Sunday till closing on Wednesday J1\e; YeMJ Tree/ IYW\I 13curfv~o-rte/ VVS CAMRA PUb-oftfte; y~ 2004- The Village Pub in Dover Opening Hours vary seasonally - Food service hours: please phone to check current Tuesday-Sat 12-2. and 7-9pm hours or visit the website Sunday 12-2.30pm NB Closed Mondays NB No food on Mondays or Sunday evening We:V~WortJtv~!!! A mile and a halffrom Shepherdswell, Eythorne & Nonington, off the A2 opposite G Lydden Motor Racing Circuit between Canterbury & Dover Booking strongly advised for meals, especially Friday, Saturday and Sunday Come to our Sunday Accumulator Draw - phone or e-mail for details!! Call Peter or Kathryn on 01304 831619 I Fax 01304 832669 or & e-mall [email protected] The Newsletter of the Deal Dover Sandwich visit www.bari ••estoae.c:o.uk 10••lua'tbe••details, District branch of the Campaign for Real Ale di••ec:tioas aad up-to-date •••.eaus Issue 20 Summer 2004 Printed at Adams the Printers, Dover (j\;:~:) Channel Draught Issue 20 • Summer 2004 ~ I CONTENTS I 3 Events diary 28 Channel View 4 Local News 31 Great British Beer elcome to the 2004 Summer edition of Channel Draught, somewhat 14 The Cowshed Pilgrimage Festival 2004 W shorter you will note, than our bumper Spring edition. -

Crystal Reports Activex Designer

Registered applications for week ending 05/05/2017 DOVER DISTRICT COUNCIL Ash 17/00453 Display of 2no. illuminated Sites East & West Side, Great BK advertisement hoardings Knell Farm, Junction of A257 &, (retrospective) Knell Lane, Ash, CT3 2ED 17/00481 Prior approval for a proposed Southlands Farm, Knell Lane, Ash , KEV change of use of agricultural CT3 2EE building to a dwellinghouse Deal 17/00312 Erection of 33no. dwellings, creation Land rear of 135-145 and AMF of new access road, parking and including, 147 St Richards Road, landscaping (existing dwelling to be Deal, CT14 9LD demolished) 17/00334 Erection of a single storey side and 33 Century Walk, Deal, CT14 6AL TJ rear extension (existing outbuilding to be demolished) 17/00376 Erection of a single storey side 31 Allenby Avenue, Deal, CT14 TJ extension 9AZ 17/00411 Erection of a detached dwelling, Site at, 279 St Richards Road, VH creation of vehicular access and Deal, CT14 9LF parking 17/00425 Erection of an attached dwelling Land Adjacent to 75 Trinity Place, BK Deal, CT14 9JG 17/00460 Erection of a first floor rear 5 Cornfield Row, Deal, CT14 9FS TJ extension Dover 17/00379 Demolition of building number five Buckland Hospital, Coombe Valley DBR Road, Dover, CT17 0HD 17/00340 Installation of an ATM and J & H Convenience Store, 212 BK alterations to shutters (retrospective) London Road, Dover, CT17 0TF 17/00341 Display of two internally illuminated J & H Convenience Store, 212 BK fascia signs London Road, Dover, CT17 0TF Page 1 of 4 1 Registered applications for week ending 05/05/2017 DOVER DISTRICT COUNCIL 17/00488 Prior approval for the change of use 2B New Street, Dover, CT17 9AJ BK from offices to 3no. -

Flood Risk to Communities Dover

Kent County Council Flood Risk to Communities Dover June 2017 www.kent.gov.ukDRAFT In partnership with: Flood Risk to Communities - Dover This document has been prepared by Kent County Council, with the assistance of: • The Environment Agency • Dover District Council • The River Stour (Kent) Internal Drainage Board • Southern Water For further information or to provide comments, please contact us at [email protected] DRAFT Flood Risk to Communities - Dover INTRODUCTION TO FLOOD RISK TO COMMUNITIES 1 DOVER OVERVIEW 2 SOURCES OF FLOODING 5 ROLES AND FUNCTIONS IN THE MANAGEMENT OF FLOOD RISK 6 THE ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 6 KENT COUNTY COUNCIL 7 DOVER DISTRICT COUNCIL 9 THE RIVER STOUR (KENT) INTERNAL DRAINAGE BOARD 10 SOUTHERN WATER 10 PARISH COUNCILS 11 LAND OWNERS 11 FLOOD AND COASTAL RISK MANAGEMENT INVESTMENT 13 FLOOD RISK MANAGEMENT PLANS AND STRATEGIES 14 NATIONAL FLOOD AND COASTAL EROSION RISK MANAGEMENT STRATEGY 14 FLOOD RISK MANAGEMENT PLANS 14 LOCAL FLOOD RISK MANAGEMENT STRATEGY 15 CATCHMENT FLOOD MANAGEMENT PLANS 15 SHORELINE MANAGEMENT PLANS 16 SURFACE WATER MANAGEMENT PLANS 16 STRATEGIC FLOOD RISK ASSESSMENT (SFRA) 17 RIVER BASIN MANAGEMENT PLAN 17 UNDERSTANDING FLOOD RISK 18 FLOOD RISK MAPPING 18 HOW FLOOD RISK IS EXPRESSED 18 FLOOD MAP FOR PLANNING 19 NATIONAL FLOOD RISK ASSESSMENT 20 PROPERTIES AT RISK 21 SURFACE WATER MAPPING 22 PLANNING AND FLOOD RISK 23 PLANNING AND SUSTAINABLE DRAINAGE (SUDS) 24 KENT COUNTY COUNCIL’S STATUTORY CONSULTEE ROLE 24 EMERGENCY PLANNING 26 PLANNING FOR AND MANAGING FLOODING EMERGENCIES 26 CATEGORY 1 RESPONDERS 26 CATEGORY 2 RESPONDERS 27 KENT RESILIENCE FORUM 28 SANDBAGS 29 PERSONAL FLOOD PLANNING AND ASSISTANCE 30 FLOOD ADVICE FOR BUSINESSES 30 FLOOD WARNINGS 30 KEY CONTACTS 32 SANDWICH 33 DOVER NORTH 35 DEAL DRAFT37 DOVER WEST 39 DOVER TOWN 41 APPENDICES 43 GLOSSARY i Flood Risk to Communities - Dover INTRODUCTION TO FLOOD RISK TO COMMUNITIES This document has been prepared for the residents and businesses of the Dover District Council area. -

How Lyminge Parish Church Acquired an Invented Dedication

ANTIQUARIANS, VICTORIAN PARSONS AND RE-WRITING THE PAST: HOW LYMINGE PARISH CHURCH ACQUIRED AN INVENTED DEDICATION ROBERT BALDWIN For more than a century, the residents of Lyminge, on the North Downs in East Kent, have taken for granted that the parish church is dedicated to St Mary and St Ethelburga. Yet for many centuries before that, it was known as the church of St Mary and St Eadburg. The dedication to St Mary, the Virgin, is ancient and straightforward to explain, for it appears in the earliest of the surviving charters forLyminge dated probably to 697. 1 The second part of the dedication, whether this is correctly St Ethelburga or St Eadburg, is also likely to pre-date the Norman Conquest for both are clearly Anglo-Saxon names. But the uncertainty over the dedication invites investigation to understand who the patron saint actually is and the cause of the change, which is an unusual event by any standards. At first sight, St Ethelburga is apparently also easy to explain. Although there were a number of St Ethelburgas, the one traditionally connected with Lyminge was Queen LEthelburh2, daughter of LEthelberht I, King of Kent, and widow of Edwin, King of Northumbria. The story of her marriage to Edwin, his conversion to Christianity and the beginning of the conversion of Northumbria in the 620s was recorded by Bede, writing around a century later.3 AfterEdwin's death in battle in 633, Bede noted that LEthelburh returned to Kent where her brother Eadbald had become king. Other sources4 recounted that the king allowed his sister to retire to his estate at Lyminge where she established a 'minster'5 and subsequently died in 647.6 A dedication to St Ethelburga makes sense in the historical context ofLyminge. -

Walking Cycling Map Update Leaflet

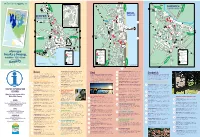

– cliffs country.org.uk white R ic Whitfield Hill h GAZEN SALTS CLIFFS & CASTLES CYCLE ROUTE 1 b S o NATURE a r o C n RESERVE T u WHITFIELD d o h g o l Canterbury e h l w London e R A2 g n M o CLIFFS & CASTLES e R a a SANDWICH R r d d t i CYCLE ROUTE 1 o n S th Menzies Road a r a o ne d Ark La N P red f t Al r e e St TOWN MAP n tr Dolphi i S are n er Squ M et c P 4 Honeywood Rd e i d d s THE SANDWICH WAY a Dover Transport d s A257 TO CYCLE ROUTE 15 o l T e St S e Exchang R w E t CANTERBURY Museum D w S n r o r e o N t & LONDON R e e r R t eet A e . t tr E s S H et e t e e e tr H r G S s o T r t Dover District e i iffin i S g t T d A W d C aR c h t W 5 a Council Offices h F a o e G o S r o b S N o e O Silver St a t R e r l r M e P t r E e e l t S t s e L A DEAL s o a t S RIVER STOUR R S h I n R W Golden St g 6 5 c 7 t s o Tesco e N e s S r w r t St O a O S e t B t d u m T r r e T Dover e a e e h e t t TOWN MAP 6 A2 t a e S R r C 5 Extra e i c t r t r 2 a e F h e r V t A S S i e E c k Parkway u t a D M r Laner t e a i g e d e e e d St t y pin r p t o l C t r Melbourne Avenue e e d e S a e 8 o G S R r g u h n t i l o t d i n c - r S n i count d t U l U e n St io H r n e p R D R d t u w Dover District e w e o Lane r e i e t B s o o g B l f e L k h B S r c Leisure Centre e i t t S r r h e S t t Potter St. -

Folkestone & Hythe District Heritage Strategy

Folkestone & Hythe District Heritage Strategy Appendix 1: Theme 11 Archaeology PROJECT: Folkestone & Hythe District Heritage Strategy DOCUMENT NAME: Appendix 1 - Theme 11: Archaeology Version Status Prepared by Date V01 INTERNAL DRAFT F Clark 08.03.16 Comments – First draft of text. No illustrations or figures. Need to finalise references and check stats included. Need to check structure of Descriptions of Heritage Assets section. May also need additions from other theme papers to add to heritage assets – for example defence heritage. Version Status Prepared by Date V02 INTERNAL DRAFT F Clark 23.08.17 Comments – Same as above with some corrections throughout. Version Status Prepared by Date V03 RETURNED DRAFT D Whittington 16.11.18 Update back from FHDC Version Status Prepared by Date V04 CONSULTATION S MASON 29.11.18 DRAFT Final check and tidy before consultation – Title page added, pages numbered 2 | P a g e Appendix 1, Theme 11 - Archaeology 1. Summary The district is rich in archaeological evidence beginning from the first occupations by early humans in Britain 800,000 years ago through to the twentieth century. The archaeological remains are in many forms such as ruins, standing monuments and buried archaeology and all attest to a distinctive Kentish history as well as its significant geographical position as a gateway to the continent. Through the district’s archaeology it is possible to track the evolution of Kent as well as the changing cultures, ideas, trade and movement of different peoples into and out of Britain. The District’s role in the defence of the country is also highlighted in its archaeology and forms an important part of the archaeological record for this part of the British southern coastline. -

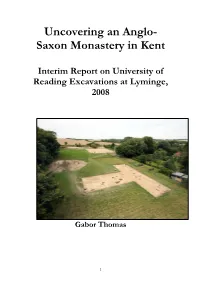

Saxon Monastery in Kent

Uncovering an Anglo- Saxon Monastery in Kent Interim Report on University of Reading Excavations at Lyminge, 2008 Gabor Thomas 1 Landscapes of the Anglo-Saxon Conversion: University of Reading Excavations at Lyminge, Kent, 2008 The following presents provisional results of the inaugural year of open-area excavation by the University of Reading within the precincts of the Anglo-Saxon monastic site of Lyminge, Kent. This work forms part of a wider project entitled ‘Landscapes of Conversion: the Anglo-Saxon Church within the Kingdom of Kent’, which seeks to construct a comparative framework in which to interpret and contextualize the evidence garnered from Lyminge. Historical and archaeological background The historical context surrounding the Anglo-Saxon monastery of St Mary’s, Lyminge has received full treatment in the Project Design (Thomas 2005). Since the initiation of the excavations a critical analysis of the historical sources relating to Lyminge minster has appeared in print (Kelly 2006). Kelly’s detective work has shaken many of the ‘truths’ surrounding the foundation legend of Lyminge minster derived from the largely post-Conquest hagiographical tradition associated with the Kentish saint, Mildrith (Rollason 1982). It is from this source that Lyminge derives its association with its founding abbess, the historical figure, Æthelburh, widow of King Edwin of Northumbria and daughter of King Æthelberht I of Kent, and with her its foundation date of A.D. 633. Contrary to received wisdom, Kelly points out that a Christian site of this comparatively early date was more likely to have been non-monastic in character, perhaps taking the form of a royal mortuary chapel. -

The River Stour (Kent) Internal Drainage Board

THE RIVER STOUR (KENT) INTERNAL DRAINAGE BOARD Minutes of the Meeting of the Board held at 2.00pm on Thursday 3 November 2016 In the Board Room at the Canterbury City Council Offices, Military Road, Canterbury, CT1 9SN PRESENT Mr M J G Tapp (Chairman), Mr A D Linfoot OBE (Vice Chairman), Councillor M J Burgess, Councillor M Conolly, Mr P S Dunn, Councillor A K Hicks, Mr P Howard, Councillor M Martin, Councillor M Ovenden, Councillor P J F Sims, Councillor D O Smith, Mr G R Steed, Mr M P Wilkinson, Mr P Williams and Mrs G Wyant. WELCOME The Chairman welcomed Ms D McNamara (Incident Response Team Leader – Upper & Lower Stour Area, Environment Agency), Mr I Nunn (FCRM Operations Manager for KSL, Environment Agency), Mr D Godden (IDB Contracts Manager, Rhino Plant Hire). The Chairman also welcomed Ms C Donaldson (Carol Donaldson Associates). IN ATTENDANCE Also in attendance were Mr J E Dilnot (Engineering Assistant), Mr P N Dowling (Clerk & Engineer to the Board) and Ms A Eastwood (Finance & Rating Officer). APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE Apologies for absence were received from Councillor S Walker, Mr P E Dyas and Mr J F E Smith. ELECTION OF A CHAIRMAN FOR THE PERIOD ENDING NOVEMBER 2017 In accordance with the Land Drainage Act 1991 and the Board’s Rules and Standing Orders there is a requirement for the Board to elect a Chairman for the ensuing year. Mr A D Linfoot proposed that Mr M J G Tapp be re-elected to the post of Chairman, this proposal was seconded by Councillor M Martin.