A Systematic Review of Presumed Consent Systems for Deceased Organ Donation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research : Code of Practice and Standards

�;HTA • Human Tissue Authority £ Research Code of Practice and Standards Published: 3 April 2017 Code E: Research Contents Introduction to the Human Tissue Authority Codes of Practice .................................. 3 Introduction to the Research Code ............................................................................. 5 The role of HTA in regulating research under the Human Tissue Act 2004 ............ 5 Scope of this Code .................................................................................................. 5 Offences under the HT Act ...................................................................................... 6 Structure and navigation ......................................................................................... 6 Relevant material and research ................................................................................. 7 What is research? ................................................................................................... 7 What is relevant material? ....................................................................................... 7 Access to tissue from the living ............................................................................... 9 Access to tissue from the deceased ..................................................................... 10 Research involving stillborn babies or infants who have died in the neotatal period .. 11 Consent ................................................................................................................... -

Exploring Vigilance Notification for Organs

NOTIFY - E xploring V igilanc E n otification for o rgans , t issu E s and c E lls NOTIFY Exploring VigilancE notification for organs, tissuEs and cElls A Global Consultation e 10,00 Organised by CNT with the co-sponsorship of WHO and the participation of the EU-funded SOHO V&S Project February 7-9, 2011 NOTIFY Exploring VigilancE notification for organs, tissuEs and cElls A Global Consultation Organised by CNT with the co-sponsorship of WHO and the participation of the EU-funded SOHO V&S Project February 7-9, 2011 Cover Bologna, piazza del Nettuno (photo © giulianax – Fotolia.com) © Testi Centro Nazionale Trapianti © 2011 EDITRICE COMPOSITORI Via Stalingrado 97/2 - 40128 Bologna Tel. 051/3540111 - Fax 051/327877 [email protected] www.editricecompositori.it ISBN 978-88-7794-758-1 Index Part A Bologna Consultation Report ............................................................................................................................................7 Part B Working Group Didactic Papers ......................................................................................................................................57 (i) The Transmission of Infections ..........................................................................................................................59 (ii) The Transmission of Malignancies ....................................................................................................................79 (iii) Adverse Outcomes Associated with Characteristics, Handling and Clinical Errors -

Could I Be a Living Kidney Donor?

Could I be a living kidney donor? www.organdonation.nhs.uk [email protected] 0300 123 23 23 “Since donating my kidney a number of people have approached me and told me what an amazing person I am. I don’t feel it, I just feel like a normal person who helped someone a little less fortunate than myself.” Carrie, donated a kidney to stranger in 2014 2 Could I be a living kidney donor? A living kidney donor is a person who gives one of their healthy kidneys to someone with kidney failure who needs a transplant (the recipient). This could be a friend or family member, or someone they do not already know. In the UK living kidney transplants have been performed since 1960 and currently around 1,100 such operations are performed each year, with a very high success rate. A kidney transplant is transformational for someone with kidney disease, whether or not they are already having dialysis treatment. Volunteering to offer a kidney is a wonderful thing to do, but it is also an important decision and there are lots of things for you to consider. We hope this information will answer some of the questions that you may have. You will find a glossary on page 15 that will explain some of the more technical terms or abbreviations that are used if these have not been explained in the text itself. These are underlined to help you. Why do we need more living kidney donors? • There are currently more than 5000 people in UK with kidney disease who are on the National Transplant List in need of a kidney – and the numbers are growing • Hundreds of people in the UK die each year in need of a kidney transplant • Unfortunately there are not enough kidneys donated from people who have died for everyone who needs a transplant • The average waiting time for a kidney transplant from someone who has died is approximately three years. -

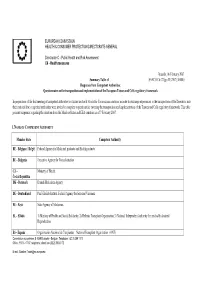

Summary Table of Responses from Competent Authorities

EUROPEAN COMMISSION HEALTH & CONSUMER PROTECTION DIRECTORATE-GENERAL Directorate C - Public Health and Risk Assessment C6 - Health measures Brussels, 06 February 2007 Summary Table of SANCO C6 CT/gcs D (2007) 360045 Responses from Competent Authorities: Questionnaire on the transposition and implementation of the European Tissues and Cells regulatory framework In preparation of the first meeting of competent authorities on tissues and cells which the Commission convenes in order to exchange experiences in the transposition of the Directives into their national law, competent authorities were invited to complete a questionnaire covering the transposition and implementation of the Tissues and Cells regulatory framework. This table presents responses regarding the situation from the Member States and EEA countries as of 7 February 2007. 1. NAME OF COMPETENT AUTHORITY Member State Competent Authority BE - Belgique / België Federal Agency for Medicinal products and Health products BU - Bulgaria Executive Agency for Transplantation CZ - Ministry of Health Česká Republika DK - Denmark Danish Medicines Agency DE - Deutschland Paul-Ehrlich-Institut, Federal Agency for Sera and Vaccines EE - Eesti State Agency of Medicines EL - Elláda 1) Ministry of Health and Social Solidarity, 2) Hellenic Transplant Organisation 3) National Independent Authority for medically Assisted Reproduction ES - España Organización Nacional de Trasplantes – National Transplant Organization (ONT) Commission européenne, B-1049 Brussels – Belgium. Telephone : (32.2) 299 11 -

Human Tissue Authority

Annual report and accounts 2019/20 Human Tissue Authority Annual report and accounts 2019/20 Annual report and accounts 2019/20 Human Tissue Authority Human Tissue Authority Annual report and accounts 2019/20 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Schedule 2(16) of the Human Tissue Act 2004. Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 7 July 2020 HC 417 Annual report and accounts 2019/20 Human Tissue Authority © Human Tissue Authority copyriGht 2020 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.Gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3. Where we have identified any third-party copyriGht information you will need to obtain permission from the copyriGht holders concerned. Any enquiries related to this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] This publication is available at www.Gov.uk/official-documents ISBN 978-1-5286-1873-1 CCS0420471370 07/20 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Annual report and accounts 2019/20 Human Tissue Authority Contents Foreword 6 Performance 8 Overview ...................................................................................................................................... 9 Performance analysis ............................................................................................................... 17 Accountability 24 Corporate Governance -

HTA) Welcomes the Opportunity to Respond to This Consultation

This response was submitted to the consultation held by the Nuffield Council on Bioethics on Give and take? Human bodies in medicine and research between April 2010 and July 2010. The views expressed are solely those of the respondent(s) and not those of the Council. The Human Tissue Authority 1. The Human Tissue Authority (HTA) welcomes the opportunity to respond to this consultation. 2. The HTA regulates the storage and use of dead bodies; the removal, storage and use of material from a dead body; and the storage and use of material from the living. Established by the Human Tissue Act 2004 (the Act), we began regulating in 2006. Created against the backdrop of the Alder Hey and Bristol Royal Infirmary Inquiries we have been determined to learn from these tragedies and address the failings they highlighted. 3. The HTA is also one of two Competent Authorities under the EU Tissues and Cells Directive, under which we regulate the human application sector. Under the Act we regulate: Anatomy Post mortem Public display Research Living organ donation 4. The thread which links each of these sectors, and the overriding principle of our regulation, is the requirement of consent. With very limited exceptions, the Act requires consent to be in place prior to bodily material being removed, stored or used. 5. For the first four sectors listed we are responsible for licensing and inspecting establishments carrying out that activity. Our Regulation Managers are trained to assess licensing applications, inspect premises, apply conditions where necessary and offer advice and guidance. 6. Our role in living organ donation is central, ensuring that the donor is consenting freely. -

Infectious Disease Transmission in Solid Organ Transplantation

Review Infectious Disease Transmission in Solid Organ Transplantation: Donor Evaluation, Recipient Risk, and Outcomes of Transmission SarahL.White,PhD,1 William Rawlinson, FRACP, FRCPA, PhD,2,3 Peter Boan, FRACP, FRCPA,4,5 Vicky Sheppeard, FAFPHM,6 Germaine Wong, FRACP, PhD,7,8,9 Karen Waller, MBBS,1 Helen Opdam, FRACP, FCICM,10,11 John Kaldor, PhD,12 Michael Fink, MD, FRACS,10,13 Deborah Verran, MD, FRACS,14 Angela Webster, PhD, FRCP, FRACP,7,9 Kate Wyburn, FRACP, PhD,1,15 Lindsay Grayson, MD, FRACP, FAFPHM, FRCP, FIDSA,10,13 Allan Glanville, MD, FRACP,16 Nick Cross, MD, PhD,17 Ashley Irish, FRACP,18,19 Toby Coates, FRACP, PhD,20,21 Anthony Griffin, FRACS,22 Greg Snell, MD, FRACP,23 StephenI.Alexander,MD,FRACP,8 Scott Campbell, FRACP, PhD,24 Steven Chadban, FRACP, PhD,1,15 Peter Macdonald, MD, FRACP, PhD,25,26 Paul Manley, FRACP,27 Eva Mehakovic,11 Vidya Ramachandran, MBBS,2 Alicia Mitchell, PhD,16,28,29 and Michael Ison, MD30 Abstract. In 2016, the Transplantation Society of Australia and New Zealand, with the support of the Australian Government Or- gan and Tissue authority, commissioned a literature review on the topic of infectious disease transmission from deceased donors to recipients of solid organ transplants. The purpose of this review was to synthesize evidence on transmission risks, diagnostic test characteristics, and recipient management to inform best-practice clinical guidelines. The final review, presented as a special supplement in Transplantation Direct, collates case reports of transmission events and other peer-reviewed literature, and summa- rizes current (as of June 2017) international guidelines on donor screening and recipient management. -

Organ Donation and Transplantation Activity Report 2019/20

Organ Donation and Transplantation Activity Report 2019/20 Preface This report has been produced by Statistics and Clinical Studies, NHS Blood and Transplant. All figures quoted in this report are as reported to NHS Blood and Transplant by 12 May 2020 for the UK Transplant Registry, maintained on behalf of the transplant community and National Health Service (NHS), or for the NHS Organ Donor Register, maintained on behalf of the UK Health Departments. NHS regions have been used throughout the report for convenience in comparisons with the previous year's figures. The information provided in the tables and figures given in Chapters 2-10 does not always distinguish between adult and paediatric transplantation. For the most part, the data also do not distinguish between patients entitled to NHS treatment (Group 1 patients) and those who are not (Group 2 patients). The UK definition of an organ donor is any donor from whom at least one organ has been retrieved with the intention to transplant. Organs retrieved solely for research purposes have not been counted in this Activity Report. Organ donation has been recorded to reflect the number of organs retrieved. For example, if both lungs were retrieved, two lungs are recorded even if they were both used in one transplant. Similarly, if one liver is donated, one liver is recorded even if it results in two or more transplants. The number of donors after brain death (DBD) and donors after circulatory death (DCD) by hospital are documented in Appendix I. Donation and transplant rates in this report are presented per million population (pmp): population figures used throughout this report are mid-2018 estimates based on ONS 2011 Census figures and are given in Appendix III. -

UK Living Donor Kidney Sharing Scheme

UK Living Kidney Sharing Scheme Your questions answered • Paired/Pooled Donation • Non-directed Altruistic Donor Chains www.organdonation.nhs.uk [email protected] 0300 123 23 23 This document provides information if you are thinking about donating or receiving a kidney as part of the UK Living Kidney Sharing Scheme, which include: • Paired/Pooled Donation • Altruistic Donor Chains If you are thinking about donating or receiving a kidney, we want you to know as much as possible about what is involved for you and what choices you may have. This information can be used as a guide to help you, but the scheme is quite complicated and your Coordinator will discuss this with you face-to-face in more detail to help you understand the options. You will find a glossary on Page 14 that will explain some of the more technical terms or abbreviations that are used if these have not been explained in the text itself. These are underlined to help you. 2 Paired/Pooled Donation Q1. What is paired/pooled donation? A1. If you are in need of a kidney and have someone close to you who is willing to donate (a donor) but you are incompatible with each other, because of your blood group or tissue type (HLA type), it may be possible for you to be matched with another donor and recipient pair in the same situation and for the donor kidneys to be ‘exchanged’ or ‘swapped’. For example, I need a transplant and my sister is willing to donate one of her healthy kidneys to me but she is the wrong blood group for me. -

Student Law Review

Southampton Student Law Review Southampton Law School Published in the United Kingdom By the Southampton Student Law Review Southampton Law School University of Southampton SO17 1BJ In affiliation with the University of Southampton, Southampton Law School All rights reserved. Copyright© 2016 University of Southampton. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, or stored in any retrieval system of any nature, without the prior, express written permission of the Southampton Student Law Review and the author, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed, in writing. The views expressed by the contributors are not necessarily those of the Editors of the Southampton Student Law Review. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure that the information contained in this journal is correct, the Editors do not accept any responsibility for any errors or omissions, or for any resulting consequences. © 2016 Southampton Student Law Review www.southampton.ac.uk/law/lawreview ISSN 2047 – 1017 This volume should be cited (2016) 6(1) S.S.L.R. Editorial Board 2016 Editors-in-Chief Kelly Mackenzie Supuni Perera Editorial Board Debo Awofeso Louise Cheung Onur Uraz Paulina Sikorska Simisola Akintola Acknowledgements The Editors wish to thank William S. Hein & Co., Inc. and HeinOnline for publishing the Southampton Student Law Review on the world’s largest image-based legal research collection. The Editors also wish to thank all members of Southampton Law School who have aided in the creation of this volume. Kelly Mackenzie and Supuni Perera Southampton Student Law Review, Editors-in-Chief September 2016 Table of Contents Foreword…………………………………………………………………………………………………i Professor Hazel Biggs Articles Legal Decision Making – A Christian Perspective………………………………………. -

Code of Practice and Standards

�;HTA • Human Tissue Authority £ Research Code of Practice and Standards Code E: Research Contents Introduction to the Human Tissue Authority Codes of Practice .................................. 3 Introduction to the Research Code ............................................................................. 5 The role of HTA in regulating research under the Human Tissue Act 2004 ............ 5 Scope of this Code .................................................................................................. 5 Offences under the HT Act ...................................................................................... 6 Structure and navigation ......................................................................................... 6 Relevant material and research ................................................................................. 7 What is research? ................................................................................................... 7 What is relevant material? ....................................................................................... 7 Access to tissue from the living ............................................................................... 9 Access to tissue from the deceased ..................................................................... 10 Research involving stillborn babies or infants who have died in the neotatal period .. 11 Consent .................................................................................................................... 12 Obtaining consent -

Organ and Tissue Donation Consent Manual Copy No: Effective Date: 13/01/2021

SOP5818/2 – Organ and Tissue Donation Consent Manual Copy No: Effective date: 13/01/2021 Organ and Tissue Donation Consent Manual Controlled if copy number stated on document and issued by QA (Template Version 03/02/2020) Page 1 of 33 SOP5818/2 – Organ and Tissue Donation Consent Manual Copy No: Effective date: 13/01/2021 Index 1. Summary of changes 3 2. Introduction and purpose 4 3. Considerations for planning following a referral 7 4. Faith Declaration 9 5. ODR Registered Opt-Out 11 6. Nominated / Appointed / Highest Qualifying Relationship (HQR) 13 7. Planning with the Care Team 15 8. Communicating with family 18 9. Approach for Tissue Only donation 22 10. Other Donation Considerations 23 11. Useful Information 27 12. Glossary 32 Controlled if copy number stated on document and issued by QA (Template Version 03/02/2020) Page 2 of 33 SOP5818/2 – Organ and Tissue Donation Consent Manual Copy No: Effective date: 13/01/2021 1. Summary of changes Addition of further clarity around ODR registration definitions Addition of sections relating to SOP5567 in preparation of commencement of INOAR Addition of a section around requests for repatriation of untransplanted organs to the body Addition of a step to notify DRD of any family information leaflets to be sent to family following a virtual or telephone approach and consent Change to information around use of IDL in a deemed approach Clarification around explicit consent required for Schedule purposes in a deemed scenario Addition of a reminder to agree donor family follow-up requirements. Return to index Controlled if copy number stated on document and issued by QA (Template Version 03/02/2020) Page 3 of 33 SOP5818/2 – Organ and Tissue Donation Consent Manual Copy No: Effective date: 13/01/2021 2.