The Strange Blessing of Yotzer Or

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THURSDAY, OCTOBER 3 Shacharit with Selichot 6:00, 7:50Am Mincha/Maariv 6:20Pm Late Maariv with Selichot 9:30Pm FRIDAY, OCTOBE

THE BAYIT BULLETIN MOTZEI SHABBAT, SEPTEMBER 21 THURSDAY, OCTOBER 3 Maariv/Shabbat Ends (LLBM) 7:40pm Shacharit with Selichot 6:00, 7:50am Selichot Concert 9:45pm Mincha/Maariv 6:20pm Late Maariv with Selichot 9:30pm SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 22 Shacharit 8:30am FRIDAY, OCTOBER 4 Mincha/Maariv 6:40pm Shacharit with Selichot 6:05, 7:50am Late Maariv with Selichot 9:30pm Candle Lighting 6:15pm Mincha/Maariv 6:25pm TUESDAY & WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 24-25 Shacharit with Selichot 6:20, 7:50am SHABBAT SHUVA, OCTOBER 5 Mincha/Maariv 6:40pm Shacharit 7:00, 8:30am Late Maariv with Selichot 9:30pm Mincha 5:25pm MONDAY & THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 23 & 26 Shabbat Shuva Drasha 5:55pm Maariv/Havdalah 7:16pm Shacharit with Selichot 6:15, 7:50am Mincha/Maariv 6:40pm SUNDAY, OCTOBER 6 Late Maariv with Selichot 9:30pm Shacharit with Selichot 8:30am FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 27 Mincha/Maariv 6:15pm Shacharit with Selichot 6:20, 7:50am Late Maariv with Selichot 9:30pm Candle Lighting 6:27pm Mincha 6:37pm MONDAY, OCTOBER 7 Shacharit with Selichot 6:00, 7:50am SHABBAT, SEPTEMBER 28 Mincha/Maariv 6:15pm Shacharit 7:00am, 8:30am Late Maariv with Selichot 9:30pm Mincha 6:10pm Maariv/Shabbat Ends 7:28pm TUESDAY, OCTOBER 8 - EREV YOM KIPPUR SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 29: EREV ROSH HASHANA Shacharit with Selichot 6:35, 7:50am Shacharit w/ Selichot and Hatarat Nedarim 7:30am Mincha 3:30pm Candle Lighting 6:23pm Candle Lighting 6:09pm Mincha/Maariv 6:33pm Kol Nidre 6:10pm Fast Begins 6:27pm MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 30: ROSH HASHANA 1 Shacharit WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 9 - YOM KIPPUR Main Sanctuary and Social Hall -

Ezrat Avoteinu the Final Tefillah Before Engaging in the Shacharit

Ezrat Avoteinu The Final Tefillah before engaging in the Shacharit Amidah / Silent Meditative Prayer is Ezrat Avoteinu Atoh Hu Meolam – Hashem, You have been the support and salvation for our forefathers since the beginning….. The subject of this Tefillah is Geulah –Redemption, and it concludes with Baruch Atoh Hashem Ga’al Yisrael – Blessed are You Hashem, the Redeemer of Israel. This is in consonance with the Talmudic passage in Brachot 9B that instructs us to juxtapose the blessing of redemption to our silent Amidah i.e. Semichat Geulah LeTefillah. Rav Schwab zt”l in On Prayer pp 393 quotes the Siddur of Rav Pinchas ben R’ Yehudah Palatchik who writes that our Sages modeled our Tefillot in the style of the prayers of our forefathers at the crossing of the Reed Sea. The Israelites praised God in song and in jubilation at the Reed Sea, so too we at our moment of longing for redemption express song, praise and jubilation. Rav Pinchas demonstrates that embedded in this prayer is an abbreviated summary of our entire Shacharit service. Venatenu Yedidim – Our Sages instituted: 1. Zemirot – refers to Pesukei Dezimra 2. Shirot – refers to Az Yashir 3. Vetishbachot – refers to Yishtabach 4. Berachot – refers to Birkas Yotzair Ohr 5. Vehodaot – refers to Ahavah Rabbah 6. Lamelech Kel Chay Vekayam – refers to Shema and the Amidah After studying and analyzing the Shacharit service, we can see a strong and repetitive focus on our Exodus from Egypt. We say Az Yashir, we review the Exodus in Ezrat Avoteinu, in Vayomer, and Emet Veyatziv…. Why is it that we place such a large emphasis on the Exodus each and every day in the morning and the evening? The simple answer is because the genesis of our nation originates at the Exodus from Egypt. -

{PDF} Berakhot Kindle

BERAKHOT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz | 760 pages | 07 Jun 2012 | Koren Publishers | 9789653015630 | English | Jerusalem, Israel Berakhot PDF Book Let the tanna teach regarding the recitation of the morning Shema first. The recital of the tefillah is then dealt with on similar lines and its wording is discussed. Because it says: And thou shalt eat and be satisfied and bless. In this case, the debate is over which blessing to recite after consuming one of the seven species, the staple foods of ancient Israel that the rabbis considered to have a special spiritual status because of their association with the Holy Land. In Epstein, I. Chapter Eight, in which, incidental to the discussion of blessings associated with a meal, a list of disputes between Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel with regard to appropriate conduct at a meal and the halakhot of blessings is cited. Moses went and said to Israel: Is Bezalel suitable in your eyes? Give Feedback. Rambam Sefer Ahava , Hilkhot Tefilla ch. Seeing that a gonorrhoeic person who has an emission, although a ritual ablution is useless in his first condition, was yet required by the Rabbis to take one, how much more so a woman who becomes niddah during sexual intercourse, for whom in her first condition a ritual ablution was efficacious! XXII, If, as mentioned above, the halakhic portion directed us from the abstract to the concrete, the direction provided by the aggadic section is from the concrete to the abstract. Which proves that the grace before food is not Biblical. Hidden categories: Disambiguation pages with short descriptions Short description is different from Wikidata All article disambiguation pages All disambiguation pages. -

Prager-Shabbat-Morning-Siddur.Pdf

r1'13~'~tp~ N~:-t ~'!~ Ntf1~P 1~n: CW? '?¥ '~i?? 1~~T~~ 1~~~ '~~:} 'tZJ... :-ttli3i.. -·. n,~~- . - .... ... For the sake of the union of the Holy One Blessed Be He, and the Shekhinah I am prepared to take upon myself the mitzvah You Shall Love Your Fellow Person as Yourself V'ahavta l'rey-acha kamocha and by this merit I open my mouth. .I ....................... ·· ./.· ~ I The P'nai Or Shabbat Morning Siddur Second Edition Completed, with Heaven's Aid, during the final days of the count of the Orner, 5769. "Prayer can be electric and alive! Prayer can touch the soul, burst forth a creative celebration of the spirit and open deep wells of gratitude, longing and praise. Prayer can connect us to our Living Source and to each other, enfolding us in love and praise, wonder and gratitude, awe and thankfulness. Jewish prayer in its essence is soul dialogue and calls us into relationship within and beyond. Through the power of words and melodies both ancient and new, we venture into realms of deep emotion and find longing, sorrow ,joy, hope, wholeness, connection and peace. When guided by skilled leaders of prayer and ritual, our complacency is challenged. We break through outworn assumptions about God and ourselves, and emerge refreshed and inspired to meet the challenges OUr lives offer." (-from the DLTI brochure, by Rabbis Marcia Prager and Shawn Israel Zevit) This Siddur was created as a vehicle to explore how traditional and novel approaches to Jewish prayer can blend, so that the experience of Jewish prayer can be renewed, revitalized and deepened. -

Halachic Minyan”

Guide for the “Halachic Minyan” Elitzur A. and Michal Bar-Asher Siegal Shvat 5768 Intoduction 3 Minyan 8 Weekdays 8 Rosh Chodesh 9 Shabbat 10 The Three Major Festivals Pesach 12 Shavuot 14 Sukkot 15 Shemini Atzeret/Simchat Torah 16 Elul and the High Holy Days Selichot 17 High Holy Days 17 Rosh Hashanah 18 Yom Kippur 20 Days of Thanksgiving Hannukah 23 Arba Parshiot 23 Purim 23 Yom Ha’atzmaut 24 Yom Yerushalayim 24 Tisha B’Av and Other Fast Days 25 © Elitzur A. and Michal Bar-Asher Siegal [email protected] [email protected] Guide for the “Halachic Minyan” 2 Elitzur A. and Michal Bar-Asher Siegal Shevat 5768 “It is a positive commandment to pray every day, as it is said, You shall serve the Lord your God (Ex. 23:25). Tradition teaches that this “service” is prayer. It is written, serving Him with all you heart and soul (Deut. 2:13), about which the Sages said, “What is service of the heart? Prayer.” The number of prayers is not fixed in the Torah, nor is their format, and neither the Torah prescribes a fixed time for prayer. Women and slaves are therefore obligated to pray, since it is a positive commandment without a fixed time. Rather, this commandment obligates each person to pray, supplicate, and praise the Holy One, blessed be He, to the best of his ability every day; to then request and plead for what he needs; and after that praise and thank God for all the He has showered on him.1” According to Maimonides, both men and women are obligated in the Mitsva of prayer. -

Daf Ditty Pesachim 118: Hallel Ha-Gadol

Daf Ditty Pesachim 118: Hallel Ha-Gadol Psalm 117, f. 21r in Passover Haggadah, with ritual instructions in French (Bouton Haggadah) Zürich, Braginsky Collection, B315 Expanses, expanses, Expanses divine my soul craves. Confine me not in cages, Of substance or of spirit. My soul soars the expanses of the heavens. Walls of heart and walls of deed Will not contain it. Morality, logic, custom - My soul soars above these, Above all that bears a name, 1 Above all that is exalted and ethereal. I am love-sick - I thirst, I thirst for God, As a deer for water brooks. Rav Kook, Chadarav, p. 391 They pour for him the third cup and he says grace after his meal. The fourth, and he concludes on it the Hallel and says on it the Blessing of the Song. Between these cups he may drink if he chooses, but between the third and the fourth he should not drink. Rabbi Simchah Roth writes:2 1: In the Gemara [Pesachim 117b] we are told that each of the four cups of wine during the Seder is designated for a certain mitzvah. The first is for Kiddush, the second is for the 'telling' (the 'haggadah'), the third is for Grace After Meals, and the fourth is for the Hallel. 2: In the Gemara [Pesachim 118a] a baraita is quoted: On the fourth [cup] he concludes the Hallel and recites the Great Hallel... The Great Hallel is then identified as Psalm 136, which includes the phrase 'for His kindness is everlasting' twenty-six times. (This is the view of Rabbi Tarfon, which is accepted; another view is also quoted in the baraita according to which the Great Hallel is Psalm 23.) More than one reason is offered for the inclusion of Psalm 136; the most appealing is probably that offered by Rabbi Yoĥanan: because God sits in his highest heaven and allocates food for each creature. -

This Motzai Shabbat: Selichot Begins!

August 31, 2018 – Elul 20, 5778 Flamingo E Weekly 812 Erev Shabbat, Parshat Ki Tavo | Avot Chapter 3 - 4 Candle lighting time from 6:36 pm, but no later than 7:37 pm Shabbat ends: 8:37 pm Extending Warmest Wishes for an Inspirational Shabbat Selichot Your Chabad Flamingo Week-at-a-Glance: Prayer Services, Classes & Events Erev Shabbat, Friday, August 31 Shabbat Selichot ~ Saturday, September 1 Sunday, September 2 6:30 am Maamer Moment 8:30 am Chassidic Reader ~ Lekutei Torah on Elul 8:00 am Early Minyan 6:30 am Early Minyan 9:15 am Main Shacharit Prayer Services 9:15 am Regular Minyan 7:00 am Regular Minyan 9:30 am Parents ’n Kids’ Youth Minyan 10:30 am Shabbat Youth Programs 7:00 pm Mincha and Sefer 6:15 pm Mincha, Sefer HaMitzvot 11:00 am The Teen Scene! HaMitzvot; Ma’ariv and “Timely Torah” then, 12:30 pm Congregational Kiddush and Friendly Schmooze joyous Kabbalat Shabbat Hear the Shofar Daily! and Ma’ariv! 6:20 pm Pirkei Avot Roundtable Review led by Alex Davis Shofar Blowing & HaYom Yom 6:50 pm Mincha, then communal Seudah Shlisheet follows daily Shacharit - also 8:30 pm Ma’ariv, then screening of the Rebbe’s Living Torah Video streamed LIVE on Facebook! Our Diamond Daveners! Youth Minyan: Shmuel Krybus 12:00 am Pre-Selichot Farbrengen Youth Program: Sara Levinoff 1:17 am The Inaugural Selichot Services! Important Reminder: Kiddush Honours: Seuda Shlisheet: Selichot Daily all week! The Kranc Family & Moshe Dayan Anonymous Women’s Mikvah: by appt. only Women’s Mikvah: 9:20 pm – 11:20 pm Women’s Mikvah: 8:00 – 10:00 pm Monday, September -

Shabbat Beshalah January 30, 2021 • 17 Shevat 5781

Shabbat Beshalah January 30, 2021 • 17 Shevat 5781 Annette W. Black Memorial Lecture Guest Speaker: Dr. Rebecca Cherry The Second Brain: Connections Between Our Minds and Bodies SHAHARIT Mah Tovu Page 144 Joan Wohl Birchot HaShechar (English) Page 147 Maxine Marlowe Hebrew Blessings Pages 146–148 Sandy Berkowitz Prayer After Birchot HaShechar Page 149 Suzan Fine Psalm 30 Page 167 Lorna Rosenberg Mourners Kaddish Page 168 Sandy Berkowitz Ashray Page 202 Jemma Blue Greenbaum, Melena Walters, Gali Nussbaum Psalm 150 Page 214 Sandra Berkowitz Nishmat Kol Hai Page 226 Marcia Webber Were Our Mouths (English) Page 229 Rene Smith, Carol Shackmaster Ki Kol Peh and Shochen Ad Pages 230–232 Marcia Webber Hatzi Kaddish and Barechu Page 234 Marcia Webber Yotzayr and Hakol Yoducha Pages 234–236 Marcia Webber El Adon Page 238 Marcia Webber Unto God Page 241 Margie Green, Missy Present KaAmoor and Ahavah Rabah Pages 244–246 Marcia Webber Sh’ma, V’Ahavta, and Parashat Tzitzit Pages 248–250 Rose Glantz, Rory Glantz True and Firm (English) Page 253 Claire Newman, Lilian Weilerstein Mi Chamocha Page 254 Mindy Goldstein, Sarah Ann Goldstein Shacharit Amidah, Kedushah and Kaddish Shalem Pages 256–274; 312 Mindy Goldstein, Sarah Ann Goldstein Shalom Rav Page 610 Karen Moses TORAH SERVICE Prayer Leader Pages 322–358 Amy Blum Introduction to Torah and Haftarah Readings Barbara Lerner Torah Reading ~ Beshalah, Exodus 14:26-17:16 Hertz Pentateuch (p. 269), Etz Hayim (p. 405) Readers Meryl Sussman, Idelle Wood, Rabbi Sandi Berliner, Terry Smerling, Anne Fassler, Nancy Zucker, Betsy Braun, Carra Minkoff, Pam Maman, GailSchwartz, Michelle Britchkow, Hazzan Howard Glantz Misheberach (Original composition by Susie Sommovilla) Susie Sommovilla Hatzi Kaddish Before Maftir Aliyah Page 333 Sharon Masarsky Maftir Aliyah HAFTARAH Blessings Before Haftarah Page 336 Jessica Izes, Rebecca Izes Haftarah Reading ~ Haftarah for Parashat Parah, Judges 4:4-5:31 Hertz Pentateuch (p. -

Lo-Lanu, Adonai, Lo-Lanu, Ki L'shimcha Tein Kavod, Al Chasd'cha Al Amee-Techa

Hallel - Hebrew Transliteration Contributed by Jill Maller-Kesselman Source: Lo-lanu, Adonai, lo-lanu, ki l'shimcha tein kavod, al chasd'cha al amee-techa. Lamah yomru hagoyeem, ayeih na Eloheihem. Veiloheinu vashamayim, kol asher chafeitz asah. Atzabeihem kesef v'zahav, ma-aseih y'dei adam. Peh lahem v'lo y'dabeiru, einayeem lahem v'lo yiru. Oz'nayeem lahem v'lo yishma-u, af lahem v'lo y'richun. Y'deihem v'lo y'mishun, ragleihem v'lo y'haleichu, lo yehgu bigronam. K'mohem yihyu oseihem, kol asher botei-ach bahem. Yisra-el b'tach b’Adonai, ezram u-maginam hu. Beit aharon bitchu v'Adonai, ezram umageenam hu. Yirei Adonai bitchu v'Adonai, ezram u-mageenam hu. Adonai z'charanu y'vareich, y'vareich et beit yisra-el, y'vareich et beit aharon. Y'vareich yirei Adonai, hak'tanim im hag'doleem. Yoseif Adonai aleichem, aleichem v'al b'neichem. B'rucheem atem l'Adonai, oseih shamayeem va-aretz. Hashamayeem shamayeem l'Adonai, v'ha-aretz natan livnei adam. Lo hameiteem y'hal'lu yah, v'lo kol yor'dei dumah. Va-anachnu n'vareich yah, mei-atah v'ad olam, hal'luyah. Ahavti ki yishma Adonai, et koli tachanunay. Ki hitah oz'no li, uv'yamai ekra. Afafuni chevlei mavet, um'tzarei sh'ol m'tza-uni, tzarah v'yagon emtza. Uv'sheim Adonai ekra, anah Adonai maltah nafshi. Chanun Adonai v'tzadik, veiloheinu m'racheim. Shomeir p'ta-im Adonai, daloti v'li y'hoshi-a. Shuvi nafshi limnuchay'chi, ki Adonai gamal alay'chi. -

Mourning Without a Minyan

mourning Without A Minyan t is our deepest hope that our world will soon heal. We pray that you will soon be able to Isafely recite the Mourner’s Kaddish with a minyan at Adath Israel. During the shiva, we remain at home and allow others to care for us. In the age of Covid-19, the community relies on telephone calls, Facetime, Skype, etc to fulfill the mitzvah ofnichum aveilim, providing comfort for those who are bereaved. In person visitation is not permissible. In the absence of a minyan, one is encouraged to recite one or both of the texts attached in the morning, afternoon, and evening – corresponding with Shacharit, Minchah, and Ma’ariv. For the time following shiva, we recognize that the Kaddish is a stand-in for a larger way of live – specifically the study of Torah and the fulfillment of mitzvot. Many believe that performing a mitzvah that was important to your loved one is even more praiseworthy than reciting the Kaddish. So too is the study of Torah done in their merit. If the recitation of Kaddish with a minyan is not possible, please consider doing a mitzvah that would have been meaningful to your loved one. At this precarious moment, checking in on isolated friends and relatives or donating money to support the many individuals who suddenly find themselves without an income are especially timely mitzvot. For study, you may consider reading the weekly Torah portion either in a chumash or online. Pirkei Avot (Ethics of our Fathers) is a wonderful and accessible ancient collection of wisdom that you should consider studying as well. -

Rosh Chodesh Amidot

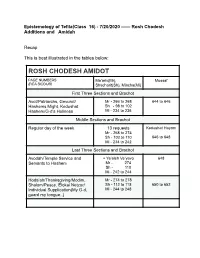

Epistemology of Tefila(Class 16) - 7/20/2020 —— Rosh Chodesh Additions and Amidah Recap This is best illustrated in the tables below: ROSH CHODESH AMIDOT PAGE NUMBERS Ma’ariv(Mr), Mussaf (RCA SIDDUR) Shacharit(Sh), Mincha(Mi) First Three Sections and Brachot Avot/Patriarchs, Gevurot/ Mr - 266 to 268 644 to 646 Hashems Might, Kedushat Sh - 98 to 102 Hashem/G-d’s Holiness Mi - 234 to 236 Middle Sections and Brachot Regular day of the week 13 requests Kedushat Hayom Mr - 268 to 274 Sh - 102 to 110 646 to 648 Mi - 234 to 242 Last Three Sections and Brachot Avodah/Temple Service and + Ya’aleh Ve’yavo 648 Servants to Hashem Mr - 274 Sh - 110 Mi - 242 to 244 Hoda’ah/Thanksgiving/Modim, Mr - 274 to 278 Shalom/Peace, Elokai Netzor/ Sh - 112 to 118 650 to 652 Individual Supplication(My G-d, Mi - 244 to 248 guard my tongue..) ROSH CHODESH AMIDOT PAGE NUMBERS Ma’ariv(Mr), Mussaf (THE KOREN SIDDUR) Shacharit(Sh), Mincha(Mi) First Three Sections and Brachot Avot/Patriarchs, Gevurot/ Mr - 257 to 261 745 to 749 Hashems Might, Kedushat Sh - 109 to 115 Hashem/G-d’s Holiness Mi - 211 to 215 Middle Sections and Brachot Regular day of the week 13 requests Kedushat Hayom Mr - 261 to 269 Sh - 115 to 125 749 to 751 Mi - 215 to 223 Last Three Sections and Brachot Avodah/Temple Service and + Ya’aleh Ve’yavo 753 Servants to Hashem Mr - 269 to 271 Sh - 127 Mi - 223 to 225 Hoda’ah/Thanksgiving/Modim, Mr - 271 to 277 Shalom/Peace, Elokai Netzor/ Sh - 127 to 135 753 to 757 Individual Supplication(My G-d, Mi - 225 to 231 guard my tongue..) Class Strategy 1. -

HIGH HOLY DAY WORKSHOP – Elul and Selichot 5 Things to Know

1 HIGH HOLY DAY WORKSHOP – Elul and Selichot 5 Things to Know About Elul Elul is the Hebrew month that precedes the High Holy Days Some say that the Hebrew letters that comprise the word Elul – aleph, lamed, vav, lamed – are an acronym for “Ani l’dodi v’dodi li,” a verse from Song of Songs that means “I am my beloved’s and my beloved is mine.” Most often interpreted as love poetry between two people, the phrase also reflects the love between God and the Jewish people, especially at this season, as we assess our actions and behaviors during the past year and hope for blessings in the coming year. Several customs during the month of Elul are designed to remind us of the liturgical season and help us prepare ourselves and our souls for the upcoming High Holidays. 1. BLOWING THE SHOFAR Traditionally, the shofar is blown each morning (except on Shabbat) from the first day of Elul until the day before Rosh HaShanah. Its sound is intended to awaken the soul and kick start the spiritual accounting that happens throughout the month. In some congregations the shofar is sounded at the opening of each Kabbalat Shabbat service during Elul. 2. SAYING SPECIAL PRAYERS Selichot (special penitential prayers) are recited during the month of Elul. A special Selichot service is conducted late in the evening – often by candlelight – on the Saturday night a week before Rosh HaShanah. 3. VISITING LOVED ONES' GRAVES Elul is also a time of year during which Jews traditionally visit the graves of loved ones.