TVS – Suzuki : Alliance Turned Sour?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

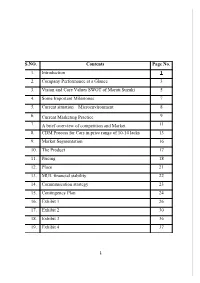

S.NO. Contents Page No. 1. Introduction 1 2. Company Performance at a Glance 3 3. Vision and Core Values SWOT of Maruti Suzuki 5 4

S.NO. Contents Page No. 1. Introduction 1 2. Company Performance at a Glance 3 3. Vision and Core Values SWOT of Maruti Suzuki 5 4. Some Important Milestones 7 5. Current situation – Microenvironment 8 6. Current Marketing Practice 9 7. A brief overview of competition and Market 11 8. CDM Process for Cars in price range of 10-14 lacks 13 9. Market Segmentation 16 10. The Product 17 11. Pricing 18 12. Place 21 13. MUL financial stability 22 14. Communication strategy 23 15. Contingency Plan 24 16. Exhibit 1 26 17. Exhibit 2 30 18. Exhibit 3 36 19. Exhibit 4 37 1 1. I NTRODUCTION Maruti Suzuki India Ltd. – Company Profile Maruti Suzuki India Ltd. (current logo) Maruti Udyog Ltd. (old logo) Maruti Suzuki is one of the leading automobile manufacturers of India, and is the leader in the car segment both in terms of volume of vehicle sold and revenue earned. It was established in February, 1981 as Maruti Udyog Ltd. (MUL), but actual production started in 1983 with the Maruti 800 (based on the Suzuki Alto kei car of Japan), which was the only modern car available in India at that time. Previously, the Government of India held a 18.28% stake in the company, and 54.2% was held by Suzuki of Japan. However, in June 2003, the Government of India held an initial public offering of 25%. By May 10, 2007 sold off its complete share to Indian financial institutions. Through 2004, Maruti Suzuki has produced over 5 million cars. Now, the company annually exports more than 50,000 cars and has an extremely large domestic market in India selling over 730,000 cars annually. -

Maruti Suzuki India Ltd

Business in India Content 1. Success Stories of Japanese companies in India a) Suzuki b) Daikin c) KUMON Global 2. Success story of McDonald in India 3. Corporate Frauds 4. GST Maruti Suzuki India Ltd. Connected For Success Sustained Performance 1.57 million cars in the financial year 2016-17 9.8% growth Hyundai, sold close to 509,707 units in 2016- 17 7 6 5 4 sales (mn) yr 2 3 sales (mn) Yr 1 2 1 0 2015-16 2016-17 Background • Founded in 1981 • To provide affordable mobility to India’s masses • Minute detail-orientation of the Japanese • Observing customers in detail, identifying their needs • Aligning the whole value chain to deliver this need at an appropriate value Guiding Principle . Osamu Suzuki’s conviction . “Cleanliness would drive effectiveness” . Check signs of inefficiency and waste . Every employee is equal . Open offices, one uniform, a common canteen for everyone from sweeper to Managing Director Philosophy that drove Maruti’s success Smaller, lighter, lesser and more beautiful “1 component, 1 gram, 1 yen” initiative . Identify cost improvements of at least ¥1 as well as weight reduction of at least one gram. Mobilized an army of about 6,000 employees Exchange programmes • Adherence to standards • Continuous improvement of standards via Kaizen • Management principles such as 3G, 3K, 3M and 5S. • Phased manufacturing programme • Balance between handholding and leveraging competition • Quality of components: increased cooperation between OEM and supplier • Financially responsible: Displaying real profits in books • Create more value than potential tax “savings” Digital training academy • First large-scale deployment of satellite broadband solution • Facilitating training in a corporate environment. -

Eicher Motors

Techno Funda Pick SiScrip IDiI-Direct Co de AiAction Target UidUpside Maruti Suzuki MARUTI Buy in the range of 5770-5910 6640.00 14% Eicher Motors EICMOT Buy in the range of 23300-23600 27450.00 17% Time Frame: 6 Months Research Analysts Dharmesh Shah [email protected] Nishit Zota [email protected] January 27, 2017 Techno Funda Pick: Maruti Suzuki (MARUTI) Time Frame: 6 Months CMP: | 5885. 00 BiBuying Range: | 5770-5910 Tt|Target: | 6640. 00 UidUpside: 14% Stock Data Key technical observations Recommended Price 5770-5910 The share price of Maruti has remained in a secular uptrend since 2014 as it continues to form higher peak and higher Price Target 6570 trough in all time frame and has consistently generated superior returns for investors over the long term. Within this structural bull run, the stock has undergone periodic phases of consolidation providing fresh entry opportunities for 52 Week High 5974 medium term players to ride the uptrend. We believe the consolidation over the last three months has approached 52 Week Low 3193 maturity and the stock provides a good entry opportunity for medium term investors. 50 days EMA 5474 The stock rebounded from a major support area ... 200 days EMA 4995 The stock after hitting a life-time high of | 5974 in the first week of November 2016 has entered a corrective 52 Week EMA 4888 consolidation phase to work off the excesses post the breakout rally from March 2016 low of | 3185 to the life-time *Recommendation given on i-click to gain on January high of 5974. -

Auto, IT Firms Lead Growth Surge

ADVANCE TAX COLLECTION Auto, IT firms lead growth surge SHRIMI CHOUDHARY such as State Bank of India (SBI) and KEY CONTRIBUTORS New Delhi, 22 June ICICI Bank reported lower (but dou- Amount paid (in ~ cr) YoY growth (%) ble-digit) growth in tax payment. Maruti Suzuki 150 200 Tech Mahindra 190 35 Sharp growth in advance tax payment According to officials, the first- by India Inc has been led mainly by quarter numbers have been compared Hero Motocorp 126 96 SBI 1,910 21 automakers and technology giants with the beginning of the pandemic- TCS 1,160 65 HUL 397 20 including Maruti Suzuki, Hero induced lockdown, so automatically L&T 30 50 Cipla 126 20 MotoCorp, Tata Consultancy (TCS), the figures showed a sharp jump. The and Infosys. second instalment will have a clearer P&G 32 45 NTPC 485 10 These four companies reported a picture, they said. Infosys 720 44 Dr Reddy’s 60 9 jump between 44 per cent and 200 per Meanwhile, final advance tax col- ICICI Bank 800 39 HDFC Bank 2,100 8 cent in the April-June quarter of this lection by companies showed 51 per financial year on account of a low base. cent growth (YoY) for the first quarter. Note: Figures for April 1-June 21 Source: CBDT sources Even top financial institutions Turn to Page 13 > > FROM PAGE 1 Auto, IT firms lead growth surge Earlier, the preliminary data impact on the companies’ increased its tax outflow by Suzuki paid ~150 crore. showed a growth rate of 146 growth. 35 per cent at ~190 crore. -

Equity Strategy

FOR EXTERNAL DISTRIBUTION TO THE FOLLOWING GROUP OF CUSTOMERS ONLY: 1. Accredited Investors (Singapore: Priority Banking). Further distribution of this publication to other group(s) is STRICTLY PROHIBITED. India Top Picks equity strategy This reflects the views of the Wealth Management Group equities | 07 March 2014 Sensex consolidating in a narrow range Contents No changes to our Top Picks this month Sensex consolidating in a narrow range 1 On Watch: India Top Picks 2 – Maruti Suzuki (MSIL IN) to Cut (waiting for a rebound) India Top Picks Review 2 – Tata Power (TPWR IN) and HPCL (HPCL IN) or Oil India Range-bound till elections 7 (OINL IN) under consideration to Add Technical Commentary 8 Indian markets were up last month because of better-than- India Top Picks – Results Update 18 expected inflation data and pre-election opinion polls suggesting Sector – Performance & Valuations 19 that the BJP-led coalition is the frontrunner for forming the next List of Equity Market Commentary Publication 21 government at the Centre. Important Information 22 Of the stocks we highlight, we believe those with the most favourable technicals are Cipla (CIPLA IN), Lupin (LPC IN) and Tech Mahindra (TECHM IN). We would advocate investors consider adding to these names at current levels. In the Interim Union Budget, the Finance Minister surprised the market by announcing that the FY14 fiscal deficit would be 4.8%, 20bps lower than previously forecast. Other highlights include the lack of populist measures ahead of the budget and excise duty Rob Aspin, CFA reduction in automobiles, capital goods and non-consumer Head, Equity Investment Strategy durables. -

A Fundamental Analysis of Indian Automobile Industry with Special Reference to Tata, Maruti & Mahindra & Mahindra

International Journal of Marketing, Sales and Brand Management Volume 1 Issue 2 A Fundamental Analysis of Indian Automobile Industry with Special Reference to Tata, Maruti & Mahindra & Mahindra Mukund S Assistant Professor Department of M.B.A Marian International Institute of Management, Kuttikkanam, Kerala Corresponding Author’s email: [email protected] DOI: http://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.3626835 Abstract The intrinsic value or the real value of any stock should be known to the investor prior to the initiation of investment in the particular company. Therefore fundamental analysis can be used to find out the intrinsic value. Fundamental analysis is based on certain factors including industry, competition, operational efficiency, dividend policy, capital structure, ratios etc. Those factors tend to change according to the industry and economy. Indian automobile industry had witnessed a growth rate of 8 % during 2019-20. The fuel prices have played an important role in the growth of automobile industry when it comes to price sensitive consumers in India. This study has attempted to analyze the fundamental components of three Indian made automobiles by using various financial and statistical techniques. Maruti stands No. 1 in the segment followed by TATA. Keywords: Automobile Industry, Dividend policy, Fundamental analysis, Operational efficiency, Ratios. INTRODUCTION to sales. 2017-18 can be considered as Indian automobile industry is a lucrative their best time of sales. It marked a double industry which is currently one of the digit growth rate from 1st April 2017 to largest markets in the world with regards 31st March 2018. We have taken three 1 Page 1-9 © MANTECH PUBLICATIONS 2019. -

Fuel Consumption from Light Commercial Vehicles in India, Fiscal Year 2018–19

WORKING PAPER 2021-02 © 2021 INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL ON CLEAN TRANSPORTATION JANUARY 2021 Fuel consumption from light commercial vehicles in India, fiscal year 2018–19 Author: Ashok Deo Keywords: CO2 standards, fleet average fuel consumption, mini truck, pickup truck, greenhouse gas emissions Introduction This paper examines the fuel consumption of new light commercial vehicles (LCVs) sold in India in fiscal year (FY) 2018–19. These vehicles are the N1 segment in India, and passenger vehicles are the M1 category.1 LCVs in India are not yet subject to any carbon dioxide (CO2) emission standards, even though such standards apply to passenger cars and have proven effective in driving down test-cycle emission levels of new vehicles. This work establishes a baseline of fuel consumption for the N1 segment in India, to help regulators develop an effective CO2/fuel consumption standard. Additionally, we compare the N1 fleets for FY 2014–15, FY 2017–18, and FY 2018–19, understand the characteristics of the mini truck and pickup segments within the N1 category, and compare the performance of major LCV manufacturers in India in terms of fleet average fuel consumption. Finally, we assess the performance of India’s LCV fleet against the LCV fleet in the European Union, considering the differences in the curb weight and size of the vehicles, and examine the performance of LCV manufacturers if a star labeling standard or passenger car fuel consumption standards were to be applied. Background LCVs are used in India as “last-mile” connectivity to move goods to their final destination. The light-duty vehicle market was approximately 87% passenger cars and 13% LCVs in FY 2018 –19.2 This study focuses on India’s LCVs, which are bifurcated into two segments by the Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers (SIAM), as shown in www.theicct.org Table 1. -

India Light Vehicle Sales Update

August 2018 India Light Vehicle Sales Update Weak July Growth Due to High Base in 2017 India’s Light Vehicle (LV) wholesales inched up by a mere 1% year-on-year (YoY) to 339k units in July, over a high base in the same period a year ago. At the same time, the dispatch of vehicles to dealers was partially impacted by an eight-day truckers’ strike. The overall volume was dragged down in particular by Passenger Vehicles (PVs), which declined by 3% YoY to 274k units. It is important to point out that dealers had depleted their inventory in June 2017 to avoid paying higher taxes under the new Goods and Services Tax (GST) regime that became effective last July. This was then followed by restocking, which bolstered wholesales in July 2017. In contrast, demand for Light Commercial Vehicles (LCVs) with GVW of up to 6 tons surged by 23% YoY to 65k units in July of this year. The LCV segment is bouncing back from the negative impact of demonetization (from November 2016 to Q1 2017) and the GST implementation, while also benefiting from an improved rural economy. On a seasonally adjusted annualized rate (SAAR) basis, sales improved marginally to 4.20 mn units in July, compared to 4.19 mn units in June. While the July SAAR was lower than the record-high selling rates of 4.37 mn units in May and 4.27 mn in April, it was, nevertheless, still a very impressive performance for India, particularly since the SAAR has exceeded 4 mn units for four consecutive months. -

An Explorative Study of Brand Associations of Indian Automobile

Research Paper Volume : 5 | Issue : 1 | JANUARY 2016 • ISSN No 2277 - 8179 Management Brand Management-Alternatives: KEYWORDS : Brand Management an Explorative Study of Brand Associations alternatives, Indian automobile industry market performance, Snow Ball technique of Indian Automobile Industry Factor analysis BE, MBA, M.Phil. UGC-NET, Assistant professor Department of Business Management Mr. Manjunatha.V SBRR Mahajana First Grade College Jayalakshmi puram Mysore Karnataka 570012 India. BE MBA PhD Assistant professor DOS in MBA BIMS, Manasagangothri, and University of Dr Amulya M Mysore Karnataka India. ABSTRACT The purpose of this research is to explore and examine the Brand Management alternatives, more specifically the Brand Associations in the Indian automobile industry. The study attempts to examine and to establish the re- lationship between the market performance and the Brand Management alternatives through the establishment of Brand Image, Brand Awareness /Brand Knowledge, Brand Identity, Brand Loyalty, Perceived Quality, Brand associations. Probably the marketing Managers of the automobile companies may understand the sensitivity of Brand Associations and the extent to which they may/may not influence the market performance of the companies. Factor analysis and integrated analysis techniques are used to determine the principal components of various Brand Associations related to select automobile companies in India. The survey is conducted in the Mysore city of Karnataka state. The companies like Maruti-Suzuki, Tata motors, Toyota motors, Hyundai motors and Mahindra & Mahindra are considered for the survey. A sample of 174 passenger car users are identified by using Snow Ball technique & interviewed and the cognitive responses are noted .The research is conducted in four quarters of the year 2014 to ensure randomness and to reduce the monotony of the feedback given by the respondents. -

TVS Motors: an Emergent Leader in the History of South Indian

ABBS South Indian Business History TVS Motors: An Emergent Leader in the 10 History of South Indian Businesses Case Study Bhargavi, M. Faculty Member, Acharya Bangalore B-School (ABBS), Bengaluru Key Words: South Indian Business, Automobiles, industry accounts for 22 per cent of the country’s TVS, SWOT manufacturing Gross Domestic Product (GDP). An Introduction expanding middle class, a young population, and an increasing interest of the companies in Automobile sector is very fast growing in recent exploring the rural markets have made the two times, as many want more sophistication and wheelers segment (with 80 per cent market share) comfort. The automotive industry in India is the leader of the Indian automobile market. The one of the largest automotive markets in the world. overall passenger vehicle segment has 14 per cent It was previously one of the fastest growing market share. India is also a substantial auto markets globally, but it is currently experiencing exporter, with solid export growth expectations flat or negative growth rates. In 2009, India for the near future. Various initiatives by the emerged as Asia’s fourth largest exporter Government of India and the major automobile of passenger cars, behind Japan, South Korea, players in the Indian market are expected to make and Thailand, overtaking Thailand to become India a leader in the Two Wheeler and Four third in 2010. As of 2010, India was home to 40 Wheeler market in the world by 2020. million passenger vehicles. More than 3.7 million Market Size automotive vehicles were produced in India in 2010 (an increase of 33.9%), making India the Sales of commercial vehicles in India grew 5.3 second fastest growing automobile market in the per cent to 52,481 units in January 2015 from a world (after China). -

SOR-PART B.Xlsx

NAME OF BIDDER SCHEDULE OF RATES -SECTION-VII TENDER NO. GAIL/NCR/C&P/S44/2K18-19 (E-TENDER NO. 8000013966) SUB: ANNUAL RATE CONTRACT FOR DISCHARGING & BOOST CHARGING OF NI-CD BATTERY BANKS INSTALLED ACROSS THE NCR (O&M) PIPELINE JURISDICTION PART-B : HARYANA, PUNJAB,RAJASTHAN & DELHI FIRST CYCLE: Ampere Hour (AH ) capacity testing of Ni-Cd battrey banks under NCR(O&M), Natural Gas pipeline network. No. OF UNIT PRICE IN S MAINTENANC BATTERY UNIT PRICE IN WORDS TOTAL STATE SV / SITE NAME UOM Battery bank FIGURE PER No E BASE BANK DETAIL PER BATTERY BANK AMOUNT (RS) per Site BATTERY BANK Haryana (3029) 1 HARYANA DHARUHERA CGS DHARUHEDA 80KGL597P Nos 2 2 HARYANA 6666 BHIWADI 80KGL597P Nos 2 3 HARYANA GURGAON SV-2/ Raisina 98KBL450P Nos 2 4 HARYANA GURGAON SV-3/ Hayatpur 97KBL650P Nos 2 5 HARYANA GURGAON SV-4/ Sultanpur 20KBL650P Nos 2 6 HARYANA GURGAON SV-4/ Sultanpur A 98KBL650P Nos 2 7 HARYANA GURGAON Maruti Suzuki Manesar 277KPL100P Nos 1 8 HARYANA GURGAON HCGDL Terminal, Gurgaon 170KPL180P Nos 1 9 HARYANA GURGAON DLF Cybercity, Gurgaon 277KPL100P Nos 1 10 HARYANA GURGAON CGS Manesar 80KGL597P Nos 2 11 HARYANA FARIDABAD SV-15, RR Station,Jatoli 37KPL870P Nos 2 12 HARYANA FARIDABAD Chainsa 20KBL650P Nos 2 13 HARYANA FARIDABAD Chainsa 98KBL650P Nos 2 14 HARYANA FARIDABAD Faridabad 142KPL200P Nos 1 15 HARYANA FARIDABAD JATAULI 36KPL870P Nos 2 16 HARYANA BAWANA SV-1, Jakhouli 40KGL1024P Nos 2 IP-02, Khandwa, Yamuna 17 HARYANA HARIDWAR 76KGL768P Nos 2 Nagar 18 HARYANA LUDHIANA SV-6, Adhoya, Ambala 76KGL768P Nos 2 19 HARYANA LUDHIANA SV-7, Jalbera, Ambala 76KGL768P Nos 2 Punjab (3030) SCHEDULE OF RATES -SECTION-VII TENDER NO. -

Blackrock Global Funds India Fund A2 EUR This Fund Is Managed by Blackrock (Luxembourg) S.A

29 June, 2020 BlackRock Global Funds India Fund A2 EUR This fund is managed by BlackRock (Luxembourg) S.A. EFC Classification Equity India Price +/- Date 52wk range 27.07 EUR 0.28 26/06/2020 20.51 36.32 Issuer Profile Administrator BlackRock (Luxembourg) S.A. The India Fund seeks to maximise total return. The Fund invests at least 70% of its total Address 35 A, avenue J.F. Kennedy 1855 assets in the equity securities of companies domiciled in, or exercising the predominant part of their economic activity in, India. (The Fund may invest through its Subsidiary). City Luxembourg Tel/Fax + 352 34 2010 4201 Website www.blackrock.com Chart 5 year General Information ISIN LU0248271941 Fund Type Capitalization Quote Frequency daily 35 Quote Currency EUR Currency USD Foundation Date 28/04/2006 30 Fund Manager Andrew Swan Legal Type Investment company according to Luxembourg law UCITS Yes 25 Financial Year End 31/08/2019 Fund size 410,769,654.30 EUR 20 Minimal Order 5,000.00 USD Costs 15 Entry fee 5.00 % 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Exit fee 0.00 % vwdgroup: Operation costs 1.50 % 38 Days 200 Days Ongoing charges 1.96 % Fund Returns 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Returns 10.33 4.93 23.69 -7.72 10.06 -20.22 Category Average 6.12 2.49 24.34 -8.73 7.75 -18.25 Category Ranking 46 / 219 65 / 289 151 / 305 138 / 329 97 / 371 255 / 385 40 20 s e u l 0 a V -20 -40 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Returns Category Average Fund Ratios (end previous month) Timing YTD 1 month 6 months 1 year 3 year 5 year Performance BlackRock Global Funds India Fund A2 EUR -26.23 % -6.43 % -26.83 % -27.09 % -6.68 % -1.37 % Volatility BlackRock Global Funds India Fund A2 EUR 36.73 % 25.56 % 22.45 % 29 June, 2020 BlackRock Global Funds India Fund A2 EUR This fund is managed by BlackRock (Luxembourg) S.A.