Wild Blackberries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

F a C T S H E E T Blackberries

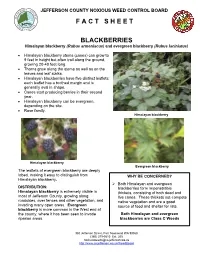

JEFFERSON COUNTY NOXIOUS WEED CONTROL BOARD F A C T S H E E T BLACKBERRIES Himalayan blackberry (Rubus armeniacus) and evergreen blackberry (Rubus laciniatus) Himalayan blackberry stems (canes) can grow to 9 feet in height but often trail along the ground, growing 20-40 feet long. Thorns grow along the stems as well as on the leaves and leaf stalks. Himalayan blackberries have five distinct leaflets; each leaflet has a toothed margin and is generally oval in shape. Canes start producing berries in their second year. Himalayan blackberry can be evergreen, depending on the site. Rose family. Himalayan blackberry Himalayan blackberry Evergreen blackberry The leaflets of evergreen blackberry are deeply lobed, making it easy to distinguish from WHY BE CONCERNED? Himalayan blackberry. Both Himalayan and evergreen DISTRIBUTION: blackberries form impenetrable Himalayan blackberry is extremely visible in thickets, consisting of both dead and most of Jefferson County, growing along live canes. These thickets out-compete roadsides, over fences and other vegetation, and native vegetation and are a good invading many open areas. Evergreen source of food and shelter for rats. blackberry is more common in the West end of the county, where it has been seen to invade Both Himalayan and evergreen riparian areas. blackberries are Class C Weeds 380 Jefferson Street, Port Townsend WA 98368 (360) 379-5610 Ext. 205 [email protected] http://www.co.jefferson.wa.us/WeedBoard ECOLOGY: . Seeds can be spread by birds, humans and other mammals. The canes often cascade outwards, forming mounds, and can root at the tip when they hit the ground, expanding the infestation . -

Adlumia Fungosa (Aiton) Greene Ex Britton

Adlumia fungosa (Aiton) Greene ex Britton Common Names: Allegheny vine, Climbing Fumitory, Mountain-fringe (1, 3) Etymology: Adlumia for John Adlum, amateur botanist of the late 18th century and early 19th century; fungosa: from the Greek ‘fung’, meaning spongy or mushroom-like (5, 7). Botanical synonyms: Fumaria fungosa (Aiton), Bicuculla fungosa (Aiton) Kuntze, Adlumia cirrhosa (Raf.), Fumaria recta (Michx.), Bicuculla fungosa (Aiton), Bicuculla fumarioides (Borkh.), Corydalis fungosa (Aiton) (3, 11, 14). FAMILY: Papaveraceae (the poppy family) Quick Notable Features: ¬ Spongy, tube-like flowers, each individual flower lasting all summer ¬ Prehensile, climbing leaves ¬ Short, often un-noticeable petiole Plant Height: A. fungosa can climb to 4m, but averages 3m (4, 8). Subspecies/varieties: none found (3) Most Likely Confused with: Rosa setigera and Rubus laciniatus, as well as other Fumarioideae species, some trifoliate Fabaceae (most notably Amphicarpaea bracteata and Lespedeza procumbens), and Ranunculaceae climbers like Clematis virginiana and C. occidentalis. Habitat Preference: A. fungosa prefers full sun, although it can tolerate shade. It is often found in moist or freshly burned woods, as well on rocky slopes and slightly acidic soils. It prefers sites protected from wind (8, 12). It was reported in 1999 in Great Smoky Mountains National Park growing on Betula lenta along streams at 2670m elevation (21). Geographic Distribution in Michigan: Allegheny-vine is found sporadically in Michigan 1 (in a geographic sense; habitat analysis may provide some explanation as to why). It is found in the following counties: Berrien, Charlevoix, Chippewa, Delta, Hillsdale, Ingham, Ishpeming, Kent, Luce, Mackinack, Menominee, Muskegon, Ottawa, Presque Isle, St. Clair, Van Buren, Washtenaw, and Wayne (2). -

Oregon City Nuisance Plant List

Nuisance Plant List City of Oregon City 320 Warner Milne Road , P.O. Box 3040, Oregon City, OR 97045 Phone: (503) 657-0891, Fax: (503) 657-7892 Scientific Name Common Name Acer platanoides Norway Maple Acroptilon repens Russian knapweed Aegopodium podagraria and variegated varieties Goutweed Agropyron repens Quack grass Ailanthus altissima Tree-of-heaven Alliaria officinalis Garlic Mustard Alopecuris pratensis Meadow foxtail Anthoxanthum odoratum Sweet vernalgrass Arctium minus Common burdock Arrhenatherum elatius Tall oatgrass Bambusa sp. Bamboo Betula pendula lacinata Cutleaf birch Brachypodium sylvaticum False brome Bromus diandrus Ripgut Bromus hordeaceus Soft brome Bromus inermis Smooth brome-grasses Bromus japonicus Japanese brome-grass Bromus sterilis Poverty grass Bromus tectorum Cheatgrass Buddleia davidii (except cultivars and varieties) Butterfly bush Callitriche stagnalis Pond water starwort Cardaria draba Hoary cress Carduus acanthoides Plumeless thistle Carduus nutans Musk thistle Carduus pycnocephalus Italian thistle Carduus tenufolius Slender flowered thistle Centaurea biebersteinii Spotted knapweed Centaurea diffusa Diffuse knapweed Centaurea jacea Brown knapweed Centaurea pratensis Meadow knapweed Chelidonium majou Lesser Celandine Chicorum intybus Chicory Chondrilla juncea Rush skeletonweed Cirsium arvense Canada Thistle Cirsium vulgare Common Thistle Clematis ligusticifolia Western Clematis Clematis vitalba Traveler’s Joy Conium maculatum Poison-hemlock Convolvulus arvensis Field Morning-glory 1 Nuisance Plant List -

Rubus Laciniatus Willd. (Rosaceae), an Introduced Species New in the Flora of Serbia and the Balkans

42 (2): (2018) 255-258 Short Communication Rubus laciniatus Willd. (Rosaceae), an introduced species new in the flora of Serbia and the Balkans Zoran Krivošej1✳, Danijela Prodanović2, Nusret Preljević3 and Bojana Veljković3 1 University of Priština, Faculty of Natural Science, Lole Ribara 29, 38220 Kosovska Mitrovica, Serbia 2 University of Priština, Faculty of Agriculture Lešak, Kopaonička bb, 38219 Lešak, Serbia 3 State University of Novi Pazar, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Vuka Karadžića bb, 36300 Novi Pazar, Serbia ABSTRACT: Rubus laciniatus has been found as a species new for the flora of Serbia during floristic investigation in the Ibar river valley. It was found on serpentine terrains near the town of Raška (SW Serbia). This is the single known locality of the given species on the Balkan Peninsula. Data on morphology, distribution, and habitat preferences of the species are provided, and the possible pathways of its introduction in Serbia are assessed. Keywords: Rubus laciniatus, blackberry, new record, Ibar river valley Received: 20 March 2018 Revision accepted: 11 July 2018 UDC: 634.71:581.95(497.11) (292.464) DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.1468362 One of the largest of plant genera, Rubus L. (Rosaceae) be in Southwest China (Lu 1983), since it is geologically has worldwide distribution and is variously classified archaic and was not seriously covered by glaciers dur- into 12 or 15 subgenera (Jennings 1988). According to ing the Quaternary (Gu et al. 1993). In Europe, the ge- The Plant List (2013), 1568 species are accepted on the nus Rubus has its centre of diversity in the Atlantic and global level and there are also 5162 unresolved names. -

Blackberry (Rubus Armeniacus/Discolor/Procerus)

Best Practices for Invasive Species Management in Garry Oak and Associated Ecosystems: Evergreen Blackberry (Rubus laciniatus) and Himalayan Blackberry (Rubus armeniacus/discolor/procerus) Assess the site characteristics and your available resources to help you decide where to take management action, what action to take, and when. These decisions should be made within the context of the overall restoration objectives (and restoration plan, if one exists). Before proceeding, be aware that it is very important to not confuse Evergreen blackberry (R. laciniatis) with the native Rubus ursinus. Evergreen blackberry is often found in association with Himalayan blackberry. If Evergreen blackberry is found alone and you are uncertain you have identified it correctly, leave it alone. Also leave it alone if it is in trailing form (rather than upright); you may damage understory vegetation by trying to remove it. a) Deciding where to take action Factor 1: Blackberry density Survey the areas in the GOE where blackberry occurs. Sketch-out and label these areas “zone 1”, “zone 2” or “zone 3” on your sketch map. Use the following descriptions: Zone 1 satellite patches (from a few canes, to a 5 foot by 5 foot patch) Zone 2 edges around larger patches Zone 3 larger patches (larger than 5’ by 5’) Where to focus your effort? Follow the Priority Principle: contain the invasive species first, then reduce its amount! The highest priority is to prevent further spread of blackberry. Only take action to reduce the “footprint” of the blackberry invasion after it is contained. Therefore Zones 1 and 2 should be your first priority, and you should only move into Zones 3 areas when blackberry has been successfully removed from Zones 1 and 2. -

1 Forest Parkland Restoration Planning

FOREST PARKLAND RESTORATION PLANNING RELATED TO BREEDING BIRDS IN SEATTLE, WA September 2014 By Jen Syrowitz, M.Env., Audubon Washington With contributions from the following people: Lisa Ciecko, City of Seattle Barbara DeCaro, City of Seattle Jon Jainga, City of Seattle Mark Mead, City of Seattle Jillian Weed, City of Seattle Michael Yadrick, City of Seattle Trina Bayard, Ph.D., Audubon Washington Gail Gatton, Audubon Washington Joey Manson, Audubon Washington Woody Wheeler, Conservation Catalyst Suggested citation: Syrowitz, J. 2014. Forest parkland restoration planning related to breeding birds in Seattle, WA. Prepared for City of Seattle Parks and Recreation. Audubon Washington. Seattle, WA. 55pp. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................................ 4 LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................................................. 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................... 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 7 Purpose ............................................................................................................................... 7 Status of Breeding Birds in Seattle..................................................................................... -

Guidebook to Invasive Nonnative Plants of the Elwha Watershed Restoration

Guidebook to Invasive Nonnative Plants of the Elwha Watershed Restoration Olympic National Park, Washington Cynthia Lee Riskin A project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Environmental Horticulture University of Washington 2013 Committee: Linda Chalker-Scott Kern Ewing Sarah Reichard Joshua Chenoweth Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Environmental and Forest Sciences Guidebook to Invasive Nonnative Plants of the Elwha Watershed Restoration Olympic National Park, Washington Cynthia Lee Riskin Master of Environmental Horticulture candidate School of Environmental and Forest Sciences University of Washington, Seattle September 3, 2013 Contents Figures ................................................................................................................................................................. ii Tables ................................................................................................................................................................. vi Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... vii Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 Bromus tectorum L. (BROTEC) ..................................................................................................................... 19 Cirsium arvense (L.) Scop. (CIRARV) -

New Jersey Strategic Management Plan for Invasive Species

New Jersey Strategic Management Plan for Invasive Species The Recommendations of the New Jersey Invasive Species Council to Governor Jon S. Corzine Pursuant to New Jersey Executive Order #97 Vision Statement: “To reduce the impacts of invasive species on New Jersey’s biodiversity, natural resources, agricultural resources and human health through prevention, control and restoration, and to prevent new invasive species from becoming established.” Prepared by Michael Van Clef, Ph.D. Ecological Solutions LLC 9 Warren Lane Great Meadows, New Jersey 07838 908-637-8003 908-528-6674 [email protected] The first draft of this plan was produced by the author, under contract with the New Jersey Invasive Species Council, in February 2007. Two subsequent drafts were prepared by the author based on direction provided by the Council. The final plan was approved by the Council in August 2009 following revisions by staff of the Department of Environmental Protection. Cover Photos: Top row left: Gypsy Moth (Lymantria dispar); Photo by NJ Department of Agriculture Top row center: Multiflora Rose (Rosa multiflora); Photo by Leslie J. Mehrhoff, University of Connecticut, Bugwood.org Top row right: Japanese Honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica); Photo by Troy Evans, Eastern Kentucky University, Bugwood.org Middle row left: Mile-a-Minute (Polygonum perfoliatum); Photo by Jil M. Swearingen, USDI, National Park Service, Bugwood.org Middle row center: Canadian Thistle (Cirsium arvense); Photo by Steve Dewey, Utah State University, Bugwood.org Middle row right: Asian -

Rubus Armeniacus, R. Bifrons

Rubus armeniacus, R. bifrons Fire Effects Information System (FEIS) FEIS Home Page Rubus armeniacus, R. bifrons SUMMARY This Species Review summarizes the scientific information about fire effects and relevant ecology of Rubus armeniacus and Rubus bifrons in the United States and Canada that was available as of 2020. Both species are nonnative, very closely related, and share the common name "Himalayan blackberry". To avoid confusion, "Himalayan blackberry" refers to R. armeniacus in this Species Review, and R. bifrons is referred to by its scientific name. Himalayan blackberry occurs in many areas of the United States and is invasive in the Pacific Northwest and California. It is considered the most invasive nonnative shrub on the West Coast, where it forms large thickets, displaces native plants, hinders wildlife movement, and causes economic losses. It is most common in mediterranean climates and prefers moist, well-drained soils. It is most invasive in low-elevation riparian, hardwood, and conifer communities. In contrast, Rubus bifrons is not considered highly invasive. Both species reproduce primarily vegetatively via layering and sprouting from their rhizomes and root crown. They also reproduce from seed, which aids establishment on new sites, including burns. The seeds are primarily dispersed by animals. The seeds have a hard coat, are dormant upon dispersal, and are stored in the soil seed bank. Fire or animal ingestion helps break seed dormancy. These blackberries are primarily early-successional, fast-growing species that prefer open, disturbed sites such as streambanks and burns. Himalayan blackberry foliage and litter can be flammable, but Himalayan blackberry may fail to burn on moist sites that lack substantial fine fuels. -

Invasive Plant Management Plan for Yosemite National Park Finding of No Significant Impact Errata Sheets

Invasive Plant Management Plan for Yosemite National Park Finding of No Significant Impact Errata Sheets September 2008 Finding of No Significant Impact Finding of No Significant Impact Invasive Plant Management Plan for Yosemite National Park Lead Agency: National Park Service September 2008 Purpose and Need Introduction This Finding of No Significant Impact documents the decision of the National Park Service to adopt a plan to manage invasive plants in Yosemite National Park and the determination that no significant impacts on the human environment are associated with that decision. The purpose of the Invasive Plant Management Plan for Yosemite National Park (Invasive Plant Management Plan) is to protect the natural, cultural, and scenic resources of the park by reducing existing invasive plant infestations and preventing the establishment and spread of invasive plants into uninfested areas of the park. The goals of the plan are: Prevention and Early Detection – Protect ecosystems from the impacts of invasive plants through an integrated and comprehensive approach that emphasizes the prevention of invasive plant spread through early detection, and treatment of newly established populations. Prioritization and Control – Remove invasive plant populations that pose the greatest threat to park resources. Outreach and Education – Educate, inform, consult, and collaborate with park employees, concessioners, visitors, park partners, private property holders, and gateway communities to address invasive plant issues. Monitoring and Research – Ensure that the invasive plant program is regularly monitored and improved, environmentally safe, and supported by science and research. Ecological Restoration – Restore ecosystems and key ecological processes that have been impacted by invasive plant species. Need The diversity of native plants in Yosemite National Park is striking; although Yosemite accounts for less than 1 percent of the land mass of California, the park contains representatives of nearly 23 percent of all native plant species in the state. -

Himalaya Blackberry

A WEED REPORT from the book Weed Control in Natural Areas in the Western United States This WEED REPORT does not constitute a formal recommendation. When using herbicides always read the label, and when in doubt consult your farm advisor or county agent. This WEED REPORT is an excerpt from the book Weed Control in Natural Areas in the Western United States and is available wholesale through the UC Weed Research & Information Center (wric.ucdavis.edu) or retail through the Western Society of Weed Science (wsweedscience.org) or the California Invasive Species Council (cal-ipc.org). Rubus armeniacus Focke Himalaya blackberry Family: Rosaceae Range: Common throughout the western United States, except in Wyoming, North and South Dakota. Habitat: Disturbed, open, moist sites such as canals, ditch banks, fencerows, roadsides, open fields, and riparian zones, in a variety of plant communities. It can also tolerate periodic flooding with brackish water. Origin: A cultivar introduced from Eurasia, originating from Armenia, quickly spread throughout Europe and the rest of the world. Impact: Himalaya blackberry is a highly competitive plant with a growth form that allows it to quickly crowd out native species. Its thickets have dense canopies allowing little light penetration and reducing the growth of understory plants. In riparian areas it can prevent access to water sources for livestock and wildlife. Western states listed as Noxious Weed: California, Oregon California Invasive Plant Council (Cal-IPC) Inventory: High Invasiveness Himalaya blackberry is an evergreen erect shrub that grows up to 10 ft tall and is climbing, mounded, or trailing. The aboveground canes are usually biennial while the roots are perennial. -

Whatcom County NWCB Fact Sheet

BLACKBERRIES Himalayan Blackberry Rubus armeniacus; Evergreen Blackberry Rubus laciniatus; Trailing Blackberry Rubus ursinus Himalayan blackberry, evergreen (or cut-leaf) blackberry and trailing (or wild) blackberry are the three common blackberries in Whatcom County. Of these, only one, trailing blackberry, is native. The other two are both introduced plants, which have become aggressive weeds here. Himalayan and evergreen blackberry are “C” Class noxious weeds on the Washington State Noxious Weed List, but not currently listed for Whatcom County. HIMALAYAN BLACKBERRY THREAT: Himalayan blackberry is the most visible blackberry of Whatcom County, growing along roadsides, over fences and other vegetation, and invading many open areas. It is native to Western Europe and was probably first introduced into North America in 1885, as a cultivated crop. Himalayan blackberry is very aggressive, reproducing both vegetatively and through seed production, and can displace native vegetation. Seeds can be spread by birds, humans and other mammals. Blackberries can form suckers off roots, and canes will root when they touch the ground, forming new plants. New plants will also readily grow from pieces of root or cane. Himalayan blackberry quickly forms impenetrable thickets, consisting of both dead and live canes. DESCRIPTION: Himalayan blackberry is a robust, sprawling, weak-stemmed shrub. The stems, called canes, grow upright at first, then cascade onto surrounding vegetation, forming large mounds or thickets of the blackberry. While some canes stay more erect, growing up to 9 feet high, others are more trailing, growing 20-40 feet long. The canes can take root at the tip, when they hit the ground, further expanding the infestation.