Guide to Voter Caging Justin Levitt and Andrew Allison June 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Letter to Robert Duncan

August 24, 2020 Robert M. Duncan Chairman USPS Board of Governors 475 L'Enfant Plaza SW Washington, DC 20260 Mr. Duncan, With an expected onslaught of requests by Americans for mail-in ballots leading up to the 2020 election and repeated attacks by President Trump on the efficacy of voting by mail, it is essential now more than ever that those at the helm of the United States Postal Service (USPS) have the best interests of the American people, and the postal service as an institution, driving their actions. Due to your extensive past involvement in voter disenfranchisement efforts, we call on you to resign from the USPS Board of Governors. Your history raises significant concerns about your commitment to ensuring free, fair, and accessible voting. During your tenure as general counsel of the Republican National Committee and as a member of the Kentucky Republican Party’s executive committee, numerous state parties — including Kentucky’s — were accused of coordinated voter suppression efforts via the banned practice of voter caging1 in an attempt to sway the 2004 election.2 Despite the Republican National Committee being forbidden from conducting voter caging by a court-ordered consent decree in 1982,3 accusations surrounding Kentucky’s 2004 election suggest that you may have overseen this type of voter suppression — primarily in majority- minority metropolitan areas.4 Your role in the potential voter suppression tactic deployed by Kentucky’s Republican Party is particularly suspect given your positions in both the state party and the Republican National Committee, as internal emails suggest the groups were in close coordination to carry out these efforts.5 Your history in Kentucky alone should be reason for grave concern about your ability to protect Americans’ access to voting. -

Guide for Scrutineers

GUIDE FOR SCRUTINEERS Form 125 Mar 2021 Role of Scrutineers It is important that candidates are familiar with the duties and responsibilities of the scrutineers that observe proceedings and act on your on your behalf. Scrutineers may observe election activities on your behalf. Up to two scrutineers per candidate may attend at one station at a time (Note: This could be changed to one scrutineer per polling station due to COVID-19 protective measures) Scrutineers will receive identification badges to wear in the polling place. Political affiliation is not permitted on the badges or elsewhere The candidate or the official agent must appoint them in writing on the Appointment of Scrutineer forms, which are available from your Returning Officer. They must have a properly completed appointment and take a declaration of secrecy to be authorized to remain in the polling place. Scrutineers must present the Appointment of Scrutineer form to the election officer and complete a declaration of secrecy at each polling station they attend On the form, you must designate the polling station(s) or registration station(s) they have been appointed to observe. The Elections Act authorizes scrutineers to remain in the polling place while the vote and the ballot count take place. Scrutineers may observe polling day activities. Election officers are authorized to ask scrutineers to leave if they obstruct the taking of the poll, communicate with an elector who has asked not to be spoken to, disrupt the voting process, or commit any offence against the Elections -

The Truth About Voter Fraud 7 Clerical Or Typographical Errors 7 Bad “Matching” 8 Jumping to Conclusions 9 Voter Mistakes 11 VI

Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE The Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law is a non-partisan public policy and law institute that focuses on fundamental issues of democracy and justice. Our work ranges from voting rights to redistricting reform, from access to the courts to presidential power in the fight against terrorism. A sin- gular institution—part think tank, part public interest law firm, part advocacy group—the Brennan Center combines scholarship, legislative and legal advocacy, and communications to win meaningful, measurable change in the public sector. ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER’S VOTING RIGHTS AND ELECTIONS PROJECT The Voting Rights and Elections Project works to expand the franchise, to make it as simple as possible for every eligible American to vote, and to ensure that every vote cast is accurately recorded and counted. The Center’s staff provides top-flight legal and policy assistance on a broad range of election administration issues, including voter registration systems, voting technology, voter identification, statewide voter registration list maintenance, and provisional ballots. © 2007. This paper is covered by the Creative Commons “Attribution-No Derivs-NonCommercial” license (see http://creativecommons.org). It may be reproduced in its entirety as long as the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law is credited, a link to the Center’s web page is provided, and no charge is imposed. The paper may not be reproduced in part or in altered form, or if a fee is charged, without the Center’s permission. -

Black Box Voting Ballot Tampering in the 21St Century

This free internet version is available at www.BlackBoxVoting.org Black Box Voting — © 2004 Bev Harris Rights reserved to Talion Publishing/ Black Box Voting ISBN 1-890916-90-0. You can purchase copies of this book at www.Amazon.com. Black Box Voting Ballot Tampering in the 21st Century By Bev Harris Talion Publishing / Black Box Voting This free internet version is available at www.BlackBoxVoting.org Contents © 2004 by Bev Harris ISBN 1-890916-90-0 Jan. 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form whatsoever except as provided for by U.S. copyright law. For information on this book and the investigation into the voting machine industry, please go to: www.blackboxvoting.org Black Box Voting 330 SW 43rd St PMB K-547 • Renton, WA • 98055 Fax: 425-228-3965 • [email protected] • Tel. 425-228-7131 This free internet version is available at www.BlackBoxVoting.org Black Box Voting © 2004 Bev Harris • ISBN 1-890916-90-0 Dedication First of all, thank you Lord. I dedicate this work to my husband, Sonny, my rock and my mentor, who tolerated being ignored and bored and galled by this thing every day for a year, and without fail, stood fast with affection and support and encouragement. He must be nuts. And to my father, who fought and took a hit in Germany, who lived through Hitler and saw first-hand what can happen when a country gets suckered out of democracy. And to my sweet mother, whose an- cestors hosted a stop on the Underground Railroad, who gets that disapproving look on her face when people don’t do the right thing. -

Randomocracy

Randomocracy A Citizen’s Guide to Electoral Reform in British Columbia Why the B.C. Citizens Assembly recommends the single transferable-vote system Jack MacDonald An Ipsos-Reid poll taken in February 2005 revealed that half of British Columbians had never heard of the upcoming referendum on electoral reform to take place on May 17, 2005, in conjunction with the provincial election. Randomocracy Of the half who had heard of it—and the even smaller percentage who said they had a good understanding of the B.C. Citizens Assembly’s recommendation to change to a single transferable-vote system (STV)—more than 66% said they intend to vote yes to STV. Randomocracy describes the process and explains the thinking that led to the Citizens Assembly’s recommendation that the voting system in British Columbia should be changed from first-past-the-post to a single transferable-vote system. Jack MacDonald was one of the 161 members of the B.C. Citizens Assembly on Electoral Reform. ISBN 0-9737829-0-0 NON-FICTION $8 CAN FCG Publications www.bcelectoralreform.ca RANDOMOCRACY A Citizen’s Guide to Electoral Reform in British Columbia Jack MacDonald FCG Publications Victoria, British Columbia, Canada Copyright © 2005 by Jack MacDonald All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system, now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher. First published in 2005 by FCG Publications FCG Publications 2010 Runnymede Ave Victoria, British Columbia Canada V8S 2V6 E-mail: [email protected] Includes bibliographical references. -

Voter Purges

ANALYSIS Voter Purges: the Risks in 2018 by Jonathan Brater† Introduction state sent county clerks the names of more than 50,000 people who were supposedly ineligible Voter purges — the often controversial practice to vote because of felony convictions. Those of removing voters from registration lists in or- county clerks began to remove voters without der to keep them up to date — are poised to be any notice. The state later discovered the purge one of the biggest threats to the ballot in 2018. list was riddled with errors: It included at least Activist groups and some state officials have 4,000 people who did not have felony convic- mounted alarming campaigns to purge voters tions.1 And among those on the list who once without adequate safeguards. If successful, these had a disqualifying conviction, up to 60 percent efforts could lead to a massive number of eligi- of those individuals were Americans who were ble, registered voters losing their right to cast a eligible to vote because they had their voting ballot this fall. rights restored back to them.2 Properly done, efforts to clean up voter rolls are The Arkansas incident also illustrates the important for election integrity and efficiency. confusion arising from many state laws that Done carelessly or hastily, such efforts are prone disenfranchise persons with past criminal to error, the effects of which are borne by vot- convictions. Nationally, more than 6 million ers who may show up to vote only to find their Americans cannot vote because of a past fel- names missing from the list. -

Our Broken Voting System and How to Repair It

THE 2012 ELECTION PROTECTION REPORT OUR BROKEN VOTING SYSTEM AND HOW TO REPAIR IT FULL REPORT PRESENTED BY ELECTION PROTECTION Led by the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law 1401 New York Ave, NW, Suite 400 Washington, DC 20005 Phone: (202) 662-8600 Toll Free: (888) 299-5227 Fax: (202) 783-0857 www.866OurVote.org /866OurVote @866OurVote www.lawyerscommittee.org /lawyerscommittee @lawyerscomm © 2013 by the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. This report may be reproduced in its entirety as long as Election Protection is credited, a link to the Coalition’s web page is provided, and no charge is imposed. The report may not be reproduced in part or in altered form, or if a fee is charged, without the Lawyers’ Committee’s permission. NOTE: This report reflects the views of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law and does not necessarily reflect the views of any other Election Protection partner or supporter. About ELECTION PROTECTION The nonpartisan Election Protection coalition—led by the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law—was formed to ensure that all voters have an equal opportunity to participate in the political process. Made up of more than 100 local, state and national partners, this year’s coalition was the largest voter protection and education effort in the nation’s history. Through our state of the art hotlines (1-866-OUR-VOTE, administered by the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, and 1-888-Ve-Y-Vota, administered by the National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials Educational Fund); interactive website (www.866OurVote.org); and voter protection field programs across the country, we provide Americans from coast to coast with comprehensive voter information and advice on how they can make sure their vote is counted. -

Sample Type B Notice for Referendum

FASCIMILE BALLOT NOTICE OF PALMYRA-EAGLE AREA SCHOOL DISTRICT ADVISORY REFERENDUM ELECTION NOVEMBER 5, 2019 OFFICE OF THE DISTRICT CLERK OF THE PALMYRA-EAGLE AREA SCHOOL DISTRICT TO THE ELECTORS OF THE PALMYRA-EAGLE AREA SCHOOL DISTRICT: Notice is hereby given of an advisory referendum election to be held in the Palmyra-Eagle Area School District, on the 5th day of November, 2019 at which the question(s), to be submitted to a vote for an advisory referendum, is shown in the sample ballot below. INFORMATION TO VOTERS Upon entering the polling place, a voter shall state his or her name and address, show an acceptable form of photo identification and sign the poll book before being permitted to vote. If a voter is not registered to vote, a voter may register to vote at the polling place serving his or her residence if the voter provides proof of residence in a form specified by law. Where ballots are distributed to voters, the initials of two inspectors must appear on the ballot. Upon being permitted to vote, the voter shall retire alone to a voting booth or machine and cast his or her ballot except that a voter who is a parent or guardian may be accompanied by the voter's minor child or minor ward. An election official may inform the voter of the proper manner for casting a vote, but the official may not in any manner advise or indicate a particular voting choice. On referenda questions when voting by paper ballot, the elector shall make a cross (X) in the square at the right of “yes” if in favor of the question, or the elector shall make a cross (X) in the square at the right of “no” if opposed to the question. -

HB 192 -- Voter Caging Prohibition Act of 2009 Sponsor: Hughes This Bill

HB 192 -- Voter Caging Prohibition Act of 2009 Sponsor: Hughes This bill establishes the Voter Caging Prohibition Act of 2009 which: (1) Prohibits any person from using lists of ineligible voters to disqualify those wishing to vote or registering to vote unless the list contains specific information such as signatures, photographs, or unique numbers showing that the individual being challenged does not meet the statutory requirements to vote because the challenged individual is dead, has been convicted of certain crimes, has changed his or her address, or is ineligible for other reasons; (2) Prohibits any person from making challenges to disqualify those wishing to vote or registering to vote based on errors on the documents used for voter registration unless the error relates to voter eligibility; (3) Prohibits the use of documents to determine whether an individual has changed his or her address and no longer qualifies to vote unless the attempted delivery of the document used to verify his or her address was at least two election cycles before the challenge; (4) Prohibits anyone except an election authority from making a challenge unless the challenger is a registered voter in the precinct in which the challenge is being made, has first-hand knowledge of the grounds of ineligibility, documents the challenge in writing, and signs an oath under penalty of perjury that the individual being challenged is ineligible. Other procedures for a non-election authority to challenge voter eligibility are specified in the bill; (5) Allows anyone rejected from voting on election day by an election authority to vote a provisional ballot; and (6) Specifies that anyone who knowingly makes a false challenge of voter eligibility will be guilty of a class one election offense. -

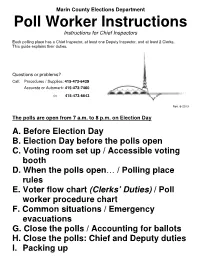

Poll Worker Instructions Instructions for Chief Inspectors

Marin County Elections Department Poll Worker Instructions Instructions for Chief Inspectors Each polling place has a Chief Inspector, at least one Deputy Inspector, and at least 2 Clerks. This guide explains their duties. Questions or problems? Call: Procedures / Supplies: 415-473-6439 Accuvote or Automark: 415-473-7460 Or 415-473-6643 Rev. 6-2013 The polls are open from 7 a.m. to 8 p.m. on Election Day A. Before Election Day B. Election Day before the polls open C. Voting room set up / Accessible voting booth D. When the polls open … / Polling place rules E. Voter flow chart (Clerks’ Duties) / Poll worker procedure chart F. Common situations / Emergency evacuations G. Close the polls / Accounting for ballots H. Close the polls: Chief and Deputy duties I. Packing up A. Before Election Day – Chief Inspector Duties ♣ Pick up a red bag at the training class. Do not open the sealed This bag contains: a black Accuvote bag, a polling place portion of the Accuvote accessibility supply bag, a Vote by Mail Ballot Box, and other bag until Election Day. supplies you will need. ♣ Use the inventory list in the red bag to make sure your red bag has all the supplies you need. ♣ Call your polling place contact (listed on your supply receipt) to make sure you can get into the polling place on Election Day by 6:30 a.m., or earlier. Important! Take this person’s contact info with you on Election Day in case you have any problems getting in. ♣ Call your Deputy Inspector(s) to tell them what time to meet you at the polling place on Election Day. -

If You Don't Know How to Get Started, Just Ask a Question

Module 8 Get Public Records and Freedom of Information Documents Public records are the kind of evidence that can stand up in a court of law. And like a box o' chocolates, you never know what you're gonna get. Guide for Requesting Public Documents Goals: Get provable documentation to find out what's really going on. Anything that's on paper or e-mail at a government agency is fair game, with a small handful of exceptions. You can't use public records request to ask a question, but you can use them to ask for documents. All you have to do is try to imagine what documents might contain answers to your questions, and request those records. It is the legal obligation of governmental agencies to provide the documents you request. How to Ask For Public Documents • Label your request "Public Records Request" if you are requesting it from a state or local governmental entity, or "Freedom of Information Act Request" if you are requesting it from a federal governmental entity. • Make sure to date it and provide an address for them to send responses. • You cannot request a record before it exists. To request election audit logs, for example, you need to wait until the election events have taken place. C ITIZEN' S T OOL K IT TO T AKE B ACK Y OUR E LECTIONS http://www.blackboxvoting.org/toolkit.pdf © Black Box Voting Inc. 2006 8/14/06 edition • Once you have requested a record, it is illegal to destroy it. If you think you might need a time-sensitive record but you aren't sure, request it as soon as possible and ask that they quote you a price for it. -

The State of the Right to Vote After the 2012 Election

S. HRG. 112–794 THE STATE OF THE RIGHT TO VOTE AFTER THE 2012 ELECTION HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION DECEMBER 19, 2012 Serial No. J–112–96 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 81–713 PDF WASHINGTON : 2013 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont, Chairman HERB KOHL, Wisconsin CHUCK GRASSLEY, Iowa DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah CHUCK SCHUMER, New York JON KYL, Arizona DICK DURBIN, Illinois JEFF SESSIONS, Alabama SHELDON WHITEHOUSE, Rhode Island LINDSEY GRAHAM, South Carolina AMY KLOBUCHAR, Minnesota JOHN CORNYN, Texas AL FRANKEN, Minnesota MICHAEL S. LEE, Utah CHRISTOPHER A. COONS, Delaware TOM COBURN, Oklahoma RICHARD BLUMENTHAL, Connecticut BRUCE A. COHEN, Chief Counsel and Staff Director KOLAN DAVIS, Republican Chief Counsel and Staff Director (II) C O N T E N T S STATEMENTS OF COMMITTEE MEMBERS Page Coons, Hon. Christopher A., a U.S. Senator from the State of Delaware ........... 6 Durbin, Hon. Dick, a U.S. Senator from the State of Illinois .............................. 4 Grassley, Hon. Chuck, a U.S. Senator from the State of Iowa ............................ 3 Leahy, Hon. Patrick J., a U.S. Senator from the State of Vermont .................... 1 prepared statement .......................................................................................... 178 Whitehouse, Hon. Sheldon, a U.S. Senator from the State of Rhode Island .....