Michelle Hamilton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Woolloomooloo-Brochure-170719.Pdf

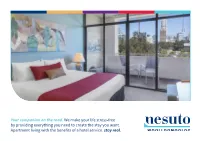

Your companion on the road. We make your life stress-free by providing everything you need to create the stay you want. Apartment living with the benefits of a hotel service. stay real. Sydney’s harbour side suburb. Nesuto Woolloomooloo is situated on the Sydney city centre fringe, in the beautiful harbour side suburb of Woolloomooloo, about 900 metres from the heart of Sydney city on the eastern side towards Potts Point. These fabulous serviced-apartments are set in a beautiful heritage listed 4 storey building, located amongst traditional Sydney terrace houses in the tree lined streets of historic Woolloomooloo, a 3-minute walk from the restaurants and bars at Finger Wharf and the legendary Harry’s Cafe de Wheels. Nesuto Woolloomooloo Sydney Apartment Hotel offers a range of self-contained Studio, One, Two and Three Bedroom Apartments, allowing you to enjoy all the comforts of home whilst providing the convenience of apartment style accommodation, making it ideal for corporate and leisure travellers looking for short term or long stay accommodation within Sydney. Nesuto. stay real. A WELCOMING LIVING SPACE Nesuto Woolloomooloo Sydney Apartment Hotel offers a range of spacious self-contained Studio, One, Two and Three Bedroom Apartments in varying styles and layouts. We offer fully equipped kitchenettes, varied bedding arrangements and spacious living areas, ideal for guests wanting more space, solo travellers, couples, families, corporate workers or larger groups looking for a home away from home experience. Our Two and Three Bedroom apartments, along with some Studio apartments, have full length balconies offering spectacular views of the Sydney CBD cityscape and Sydney Harbour Bridge. -

City of Sydney Submission on the CFFR Affordable Housing Working

City of Sydney Town Hall House City of Sydney submission 456 Kent Street Sydney NSW 2000 on the CFFR Affordable Housing Working Group Issues Paper March 2016 Contents Introduction ..........................................................................................................................2 Context: housing affordability pressures in inner Sydney ...................................................2 The City’s response to the Issues Paper ............................................................................4 Broad-based discussion questions ..................................................................................4 Model 1: Housing loan/bond aggregators .......................................................................6 Model 2: Housing trusts ...................................................................................................7 Model 3: Housing cooperatives .......................................................................................8 Model 4: Impact investing models including social impact bonds ...................................9 Other financial models to consider ................................................................................10 1 / City of Sydney response to the Affordable Housing Working Group Issues Paper Introduction The City of Sydney (the City) welcomes the initiative by the Council on Federal Financial Relations Affordable Housing Working Group (‘the Working Group’) to examine financing and structural reform models that have potential to enable increased -

Review of Environmental Factors Woolloomooloo Wastewater

Review of Environmental Factors Woolloomooloo Wastewater Stormwater Separation Project March 2016f © Sydney Water Corporation (2016). Commercial in Confidence. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced without the express permission of Sydney Water. File Reference: T:\ENGSERV\ESECPD\EES Planning\2002XXXX_Hot spots 3\20029431 Woolloomooloo sewer separation\REF Publication number: SWS232 03/16 Table of Contents Declaration and sign off Executive summary ........................................................................................................... i 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Project Background .................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Woolloomooloo Wastewater Stormwater Separation .............................................. 2 1.3 Related stormwater projects ...................................................................................... 4 1.4 Scope of this REF ........................................................................................................ 4 2. Stakeholder and community consultation .......................................................... 5 2.1 Consultation objectives .............................................................................................. 5 2.2 Social analysis ............................................................................................................. 5 2.3 Consultation -

Sydney City News February 2019

DAWES POINT / KIRRIBILLI Sydney Harbour TAR-RA Bridge Walsh Bay Sydney Harbour ROAD Barangaroo Reserve HIGHWAY Campbells Cove / HICKSON Meeliyahwool MILLERS Sydney THE Opera POINT House ARGYLE ROCKS Sydney Cove / BRADFIELD Warrane ST KENT Observatory ST HICKSON Park Garden Island ST Government Ferry House STREET BARANGAROO GEORGE CIRCULAR QUAY Farm Cove / STREET Wahganmuggalee Darling ROAD Macquarie Place D HARRINGTON A MACQUARIE RO Harbour GROSVENOR ST Conservatorium Lang BRIDGE STREET Pirrama of Music The YORK Park Park Farrer DISTRIBUTOR A Place Royal M STREET STREET A ST STREET R MARGARET R OUR NEW PLAN FORPI Botanic KIRRIBILLI HUNTER Garden P IR WYNYARD JOHN STREET SQUARE R Sydney Chifley C A DAWES POINT / A Garden M Harbour TheWynyard City of Sydney’s three fabulousH outdoor aquatic centres are the best places to Square State IL A TAR-RA Bridge STREET L Island HARRIS ST Sydney WESTERNERSKINE swim,Park picnic and play thisLibrary summer. They all have 50 metre pools for lap swimming CLARENCE Walsh KENT EXPRESSWAY SYDNEY’S NIGHTLIFE SUSSEX Bay THE STAR W LeisureSTREET in Sydney this summer Harbour as well as smaller poolsMARTIN PLACE for learners and leisure seekers. In addition, there are two Martin Y STREET L Place D WE PYRMONT RO E Last year, an extensive consultationSTE 24-hour trading will be extendedADROAD across the Sydney CBD: indoor pools, open longer hours for city workers and residents. RN PITT S DIS T process brought forward more than 10,000TRI BU HIGHWAY Campbells Cove / KING TO Barangaroo PYRMONT BAY STREET R Meeliyahwool Sydney The Y Anzac A T Reserve E people who called for more late night HICKSON Opera Maritime STREET W E Bridge proposed 24-hourET Sydney STREET Art Gallery TRE House MACQUARIE D R A T S STREET Museum Aquarium Queens of NSW CHALLIS O S areas, extended opening hours and more LER MILLERS THE Sydney Domain CO R AVE tradingMIL zones Pyrmont Bridge Square W B D Sydney Cove / PE F POINT A Tower R R AD ROCKS GardenES RD Island W HA things to do after dark. -

Gardens of History and Imagination GROWING NEW SOUTH WALES

ii Illustrations Where indicated by their individual catalogue numbers, illustrations are from the Mitchell Library, Dixson Library and the Dixson Galleries Collection, State Li- brary of NSW, Sydney. Illustrations are also drawn from the Daniel Solander Library, Royal Botanic Gardens and from private collections as indicated. Rosebank, Woolloomooloo, the Residence of James Laidley (detail), 1840, by Conrad Martens, ML DG V* / Sp Coll / Martens / 5 Digitalis purpurea, in William Curtis, Flora Londinensis, 1777, Daniel Solander Library, RBG Castle Hill, ca 1806. Watercolour, ML PX*D 379 Map. The City of Sydney, 1888, Hill, ML M3 811.17s/1888 Map. ‘County of Cumberland’, ca 1868, in Atlas of the Settled Counties of New South Wales, Basch, 1872, ML F981.01/B 1 Rosebank, Woolloomooloo, the Residence of James Laidley, 1840, by Con- rad Martens, ML DG V* / Sp Coll / Martens / 5 2 Aboriginal Fisheries, Darling River, New South Wales, ML PXA 434/12 3 Japanese garden, Hiroshima-ken, Gaynor Macdonald, 1988 4 Rainbow, Turill, Wonnarua Country, Gaynor Macdonald, 2009 5 Panoramic Views of Port Jackson, ca 1821, drawn by Major James Taylor, engraved by R Havell & Sons, Colnaghi, London, ca 1823, ML V1 / ca 1821 /6 6 Frog Rock, Wiradjuri Country, Gaynor Macdonald, 2005 7 State Ball in Australia. Kangaroo Dance, in Native Scenes, 1840–1849?, P H F Phelps, DL PX 58 8 Hand Stencils, in Album Including Drawings of Snakes and Aboriginal Rock Art, Sydney Harbour, New South Wales, 1876–1897, by J S Bray, ML PXA 192 9 Pteris tremula, in Item 07: Dried Specimens -

Sustainable Neighbourhoods in Australia Raymond Charles Rauscher · Salim Momtaz

Sustainable Neighbourhoods in Australia Raymond Charles Rauscher · Salim Momtaz Sustainable Neighbourhoods in Australia City of Sydney Urban Planning 1 3 Raymond Charles Rauscher Salim Momtaz University of Newcastle University of Newcastle Ourimbah, NSW Ourimbah, NSW Australia Australia ISBN 978-3-319-17571-3 ISBN 978-3-319-17572-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-17572-0 Library of Congress Control Number: 2015935216 Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2015 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Cover image: Woolloomooloo Square (Forbes St) developed from street closure (see Chapter 3 on Woolloomooloo). -

Art Gallery of New South Wales Expansion: Sydney Modern Heritage Impact Statement Report Prepared for the Art Gallery of NSW April 2018

Art Gallery of New South Wales Expansion: Sydney Modern Heritage Impact Statement Report prepared for the Art Gallery of NSW April 2018 Sydney Office Level 6 372 Elizabeth Street Surry Hills NSW Australia 2010 T +61 2 9319 4811 Canberra Office 2A Mugga Way Red Hill ACT Australia 2603 T +61 2 6273 7540 GML Heritage Pty Ltd ABN 60 001 179 362 www.gml.com.au GML Heritage Report Register The following report register documents the development and issue of the report entitled Art Gallery of NSW Expansion: Sydney Modern—Heritage Impact Statement, undertaken by GML Heritage Pty Ltd in accordance with its quality management system. Job No. Issue No. Notes/Description Issue Date 15-0518B 2 Revised Preliminary Draft 19 October 2017 15-0518B 3 Final—SSDA Submission 2 November 2017 15-0518B 4 Revised Final—RtS Submission Test of Adequacy 28 March 2018 15-0518B 5 Revised Final—RtS Final Lodgement 17 April 2018 Quality Assurance GML Heritage Pty Ltd operates under a quality management system which has been certified as complying with the Australian/New Zealand Standard for quality management systems AS/NZS ISO 9001:2008. The report has been reviewed and approved for issue in accordance with the GML quality assurance policy and procedures. Project Manager: Emma McGirr Project Director & Claire Nunez Reviewer: Issue No. 5 Issue No. 5 Signature Signature Position: Consultant Position: Associate Date: 17 April 2018 Date: 17 April 2018 Copyright Historical sources and reference material used in the preparation of this report are acknowledged and referenced at the end of each section and/or in figure captions. -

3.6 Reclamation and Land Consolidation 1825 to 1870S

277 3.6 Reclamation and Land Consolidation 1825 to 1870s 3.6.1 Introduction Between the 19th and mid-20th century the foreshore of Sydney Harbour was transformed from its natural state by successive phases of waterfront development. Shipping was the primary mode of transport for people and goods for much of the 19th century. Despite the development of better roadways and rail networks, local, intercolonial and international trade was reliant on the connection to the harbours and waterways. Suitable and adequate port facilities were crucial for the city’s economic development and growth. As a main area for early industry and trade activity, the Darling Harbour foreshore was radically altered by numerous land reclamations, initially for maritime infrastructural and later railway development projects. Reclamation can be broadly defined as the process of turning submerged or unusable land into land suitable for a variety of purposes. Reclamation has a long history around the world. In a global context, reclamation prior to industrialisation was primarily undertaken to create and secure land for agriculture. In urban environments, reclamation was undertaken to consolidate city waterfronts, improve defences and turn obsolete landfill sites into habitable land. From the 18th century onwards, the transition to mechanised manufacture and production processes led to extraordinary urban expansion, population growth, and industrial development. During the 19th century reclamation became more associated with the industrialisation and commercial development of urban waterfronts. In Sydney, as with other towns and cities in the industrialised world, it became an integral component of wharf construction. Reclamation also became a necessary process within broader waterway management systems, as wharf construction, reclamation and pollution from the expanding urban centre changed and adversely affected the natural depositional patterns and environment of the harbour and rivers feeding it. -

New South Wales from 1810 to 1821

Attraction information Sydney..................................................................................................................................................................................2 Sydney - St. Mary’s Cathedral ..............................................................................................................................................3 Sydney - Mrs Macquarie’s Chair ..........................................................................................................................................4 Sydney - Hyde Park ..............................................................................................................................................................5 Sydney - Darling Harbour .....................................................................................................................................................7 Sydney - Opera House .........................................................................................................................................................8 Sydney - Botanic Gardens ................................................................................................................................................. 10 Sydney - Sydney Harbour Bridge ...................................................................................................................................... 11 Sydney - The Rocks .......................................................................................................................................................... -

Appendix A: University of Sydney Overview History

APPENDIX A: UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY OVERVIEW HISTORY THE PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT OF BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS Prepared by Rosemary Kerr (Sue Rosen & Associates) ______________________________ With PRE-COLONIAL HISTORY AND DESCRIPTION by Dr Val Attenbrow, Australian Museum, and Cheryl Stanborough ______________________________ SUMMARY OF PLANNING AND BUILT FORM DEVELOPMENT by Donald Ellsmore ______________________________ OVERVIEW OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF AUSTRALIAN UNIVERSITIES by Duncan Marshall University of Sydney Grounds Conservation Plan —October 2002 Page A1 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1.1 Authorship 1.2 Using the History as a Management Tool 2. Pre-Colonial Inhabitants and Land Use 2.1 People – The Original Inhabitants 2.2 Subsistence and material culture 2.3 Locational Details And Reconstruction Of Pre-1788 Environment 3. Early History of Grose Farm and Darlington 3.1 Church, School and Crown Land 3.2 Grose Farm 3.3 Surrounding Area 3.4 Female Orphan Institution 3.5 Subdivision 3.6 Pastoralism 3.7 Darlington Area 3.8 Subdivision and Residential Development 3.9 Institute Building and Darlington School 3.10 University Extension into Darlington 4. University of Sydney Foundation and Early Development 1850-1880 4.1 Background to Foundation 4.2 Establishment of University at Grose Farm 4.3 Initial Building Program 4.4 Great Hall and East Wing of Main Building 4.5 Development of Colleges 4.6 Grounds and Sporting Facilities 5. Development of Medicine and the Sciences 1880-1900 5.1 Expansion of Curriculum 5.2 Challis Bequest 5.3 Establishment of a Medical School 5.4 The Macleay Museum 5.5 ‘Temporary’ Buildings for Sciences and Engineering 5.6 Student Facilities 5.7 Sporting Facilities 5.8 Grounds 6. -

Sydney's New Jams

Fears major bus routes will be cut Fairfax and Google like if we don’t have the newsrooms we have BY PETER HACKNEY “Light rail in Surry Hills is supposed to replace now?” There are fears major bus services serving Sydney’s these buses but down Devonshire St – an average of become Pyrmont The news might not be all bad for Fairfax inner east will be cut, with the NSW Long Term one kilometre away from current bus stops. And the though, and the close proximity to Google Transport Masterplan appearing to show that a raft of light rail [will only go] to Circular Quay, not across the housemates could present some strategic advantages for bus routes serving Darlinghurst and Surry Hills will bridge to North Sydney and beyond, as some of the BY MAX CHALMERS the struggling company. be scrapped. bus services do. A new arrangement between two of the most Maureen Henninger, a Senior Lecturer in While the masterplan does not specifically spell “This doesn’t help residents who work in the North recognisable brands in Australia has led to the Information and Knowledge Management at out the fate of the services, the blueprint for Sydney’s Sydney commercial precinct or who, for example, go radical reimagining of a Pyrmont office space. the University of Technology, Sydney (UTS), transport future does not include any bus services on to the North Sydney pool in the mornings for a swim.” Internet giant Google has moved into the said that while Google would hardly be giving Fitzroy and Albion Streets. Ms Slama-Powell said residents of Surry Hills, second floor of Fairfax’s Pyrmont offices, away any secrets, conversations with Fairfax about its social networking programs Google “All bus services on Fitzroy and Albion Streets Paddington and Darlinghurst needed to know about subleasing the space from the struggling media Plus could be fertile. -

Central Precinct Draft Strategic Vision October 2019 Central

Transport for NSW Central Precinct Draft Strategic Vision October 2019 Central Acknowledgement of country Transport for NSW respectfully acknowledges the Traditional Owners and custodians of the land within Central Precinct, the Gadigal of the Eora Nation, and recognises the importance of this place to all Aboriginal people. Transport for NSW pays its respect to Elders past, present and emerging. The vision for Central Precinct: Central Precinct will be a vibrant and exciting If you require the services of an interpreter, place that unites a world-class transport contact the Translating and Interpreting Services on 131 450 and ask them to call interchange with innovative businesses Transport for NSW on (02) 9200 0200. The interpreter will then assist you with and public spaces. It will connect the city translation. at its boundaries, celebrate its heritage and Disclaimer become a centre for the jobs of the future and While all care is taken in producing and publishing this work, no responsibility is economic growth. taken or warranty made with respect to the accuracy of any information, data or representation. The authors (including copyright owners) and publishers expressly disclaim all liability in respect of anything done or omitted to be done and the consequences upon reliance of the contents of this publication. Images The photos used within these document include those showing the existing environment as well as precedent imagery from other local, Australian and international examples. The precedent images are provided to demonstrate how they achieve some of the same outcomes proposed for Central Precinct. They should not be interpreted as a like for like example of what will be seen at Central Precinct.