Alentejo's Talha Wine Traditions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 2016 Half Case - Red

HIGHLAND FINE WINE DECEMBER 2016 HALF CASE - RED SanguIneti Cannonau Di Sardegna - Sardinia, Italy (Mixed & Red Club) $11.99 Made of 100% Cannonau, or Grenache, this fiercely Mediterranean varietal thrives in sun-soaked, arid landscapes. Rising to the occasion in the rocky, windswept vineyards of Sardegna, the vines find themselves in the capable hands of Antonio Sanguineti. In his youth, Sanguineti lost his ancestral Tuscan vineyards in familial disputes. He now relishes the opportunity to use his knowledge and passion for winegrowing. This wine is packed with ripe cherry, raspberry, plum, and pomegranate fruit notes along with some earthy/spicy nuances. It is medium bodied, juicy, pliant, and fresh with flavors of warm red berries, peppery spice, and smoky herbs. Pairs effortlessly with steak, lamb, sheep’s milk cheeses, and roasted red pepper. Delito Carinena - Aragon, Spain (Mixed & Red Club) $12.99 Delito Carinena is 100% Carignan from Carinena, Spain! Old-vine Carignan grapes, fully ripened on infertile soils in an area of warm summers, typical from Aragon. Yields have been restricted so there is enough ripe fruit character to compensate the naturally high tannins and acidity. Delito Carinena is a young red that shows aromas of blackberries and black currants mixed with mineral notes. The palate is medium- to full-bodied, with fine-grained, earthy tannins and good freshness and depth. Enjoy Delito Carinena with grilled meats, roasted duck and venison. Sean Minor Cabernet Sauvignon - Napa Valley, CA (Mixed & Red Club) $19.99 The Minor’s winery is 100% family owned and operated. Not long after Nicole and Sean Minor were married, they discovered their second largest monthly expense was wine. -

Wines of Alentejo Varieties by Season Sustainability Program (WASP) 18 23 24

Alentejo History Alentejo The 8 sub-regions of DOC the 'Alentejo' PDO 2 6 8 'Alentejano' Grape Red Grape PGI Varieties Varieties 10 13 14 The Alentejo White Grape Viticulture Season Wines of Alentejo Varieties by Season Sustainability Program (WASP) 18 23 24 Wine Tourism Alentejo Wine Grapes used in Gastronomy Wines of Alentejo blends 26 28 30 Facts and Guarantee Figures of Origin 33 36 WINES OF ALENTEJO UNIQUE BY NATURE CVRA - COMISSÃO VITIVINÍCOLA REGIONAL ALENTEJANA Copy: Rui Falcão Photographic credits: Nuno Luis, Tiago Caravana, Pedro Moreira and Fabrice Demoulin Graphic design: Duas Folhas With thanks to Essência do Vinho The AlentejoWINE REGION There is something profoundly invigorating and liberating about the Alentejo landscape: its endlessly open countryside, gently undulating plains, wide blue skies and distant horizons. The landscape mingles with the vines and cereal crops – an ever-changing canvas of colour: intensely green towards the end of winter, the colour of straw at the end of spring, and deep ochre during the final months of summer. 1 All over the Alentejo there are archaeological markers suggesting that wine has Historybeen an important part of life up to the present day. Whilst it is not known exactly when wine and viticulture was introduced to the Alentejo, there is plenty of evidence that they were already part of the day-to-day life in the Alentejo by the time the Romans arrived in the south of Portugal. It is thought that the Tartessians, an ancient civilisation based in the south of the Iberian Peninsula and heirs of the Andalusian Megalithic culture, were the first to domesticate vineyards and introduce winemaking principles in the Alentejo. -

Glutathione and Its Application in Winemaking

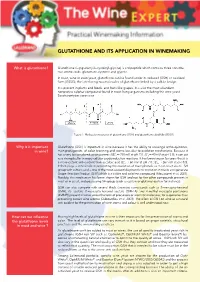

GLUTATHIONE AND ITS APPLICATION IN WINEMAKING What is glutathione? Glutathione (L-g-glutamyl-L-cysteinyl-glycine) is a tripeptide which contains three constitu- tive amino acids: glutamate, cysteine and glycine. In must, wine or even yeast, glutathione can be found under its reduced (GSH) or oxidized form (GSSG), the later being two molecules of glutathione linked by a sulfide bridge. It is present in plants and foods, and fruits like grapes. It is also the most abundant nonproteic sulphur compound found in most living organisms including the wine yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Figure 1: Molecular structures of glutathione (GSH) and glutathione disulfide (GSSG) Why is it important Glutathione (GSH) is important in wine because it has the ability to scavenge ortho-quinones, in wine? main protagonists of color browning and aroma loss due to oxidation mechanisms. Because it has a very low oxydoreduction potential (E’o=-250 mV at pH 7.0 ; E’o=-40 mV at pH 3.0), it can act as a strong buffer in many cellular oxydoreduction reactions. It has been known for years that it is a more potent anti-oxidant than ascorbic acid (E’o=+60 mV at pH 7.0 ; E’o=+267 mV at pH 3.0). It then plays a critical role in preventing the oxidation of must phenols as it can react via its –SH group with caftaric acid – one of the most susceptible phenols to oxidation in musts and generate Grape Reaction Product (GRP) which is a stable and colorless compound (Moutounet et al, 2001). Notably, this mechanism has been shown for GSH and not for the other compounds present in must or in yeast, and possessing SH-group (such as cystein or glutamyl-cystein for instance). -

International Herdade Das Barras November

GOLD MEDAL WINE CLUB Taste the Adventure! Portugal Vol. A • WITH A WINEMAKING HISTORY DATING OVER 4,000 YEARS OLD, PORTUGAL OFFERS THRILLINGLY DIFFERENT INDIGENOUS WINE GRAPE VARIETALS AND WONDERFULLY DIVERSE TERROIR . The fact that Portugal was named best wine region to visit by USA TODAY in 2014 came as no surprise to wine industry insiders. When you add the actuality that Portuguese wines have consistently placed extremely high among the world’s top wines for the past decade, you get the idea that the Portuguese are doing something right. Long a haven for dessert wines (Portuguese ports have been revered by practically everyone for the past two hundred years), modern Portuguese wineries have cropped up ever since Portugal joined the European Union in January of 1986 and international funding became available to the country’s mostly rural economy. Formerly bucolic areas suddenly became accessible and smart investors (generally Portuguese) jumped at the opportunity. No industry benefitted more than the enduring Portuguese Wine Industry. Smaller growers and wine producers received huge subsidies and grants that vastly improved winemaking facilities and vineyards. Small boutiques (quintas) revolutionized Portuguese winemaking and succeeded in establishing Portugal as an international market for more than port, madeira and Mateus. Wine growing regions suddenly sprung up in areas that had seldom seen vineyards and wineries, mostly state-of-the-art thanks to the huge influx of EU monies. Roads were widened and accompanying hotels and restaurants (as well as visitor facilities) became as fine as any in the country. Obscure regions such as this month’s featured Alentejo Region (see Region Section) benefited due to its closeness to Portugal’s main visitor stream in the Capitol of Lisbon. -

Green Wine Quinta Do Ameal Murças Terroir

Green Wine Quinta Do Ameal PVP 13,00€ VINHO VERDE AMEAL LOUREIRO VINHO VERDE AMEAL – SOLO ÚNICO CLÁSSICO 2019 2019 GRAPES: Loureiro GRAPES: Loureiro COLOUR: Light citrus color COLOUR: Clear and light citrus color AROMA: Intense, dominated by citrus fruits and floral AROMA: Floral and fruity, well combined and balanced, aromas characteristic of the Loureiro variety. typical of the very ripe grapes of the Loureiro variety. PALATE: Vibrant and balanced, with refreshing acidity PALATE: Quite complex and evolution typical of that predicts a good evolution. minimalist intervention. VINHO VERDE AMEAL – BICO VINHO VERDE AMEAL – ESCOLHA AMARELO 2020 2017 GRAPES: Castas da Região dos vinhos Verdes GRAPES: Loureiro COLOUR: Yellow with green tones. COLOUR: Clear and light citrus color AROMA: It presents an exuberant, fresh and light aroma, AROMA: Floral and fruity, orange blossom well combined dominated by citrus fruits and tropical aromas. with vanilla and smoked PALATE: Dominated by its acidity with good volume, it PALATE: Long and complex aftertaste, typical of a great has a persistent and refreshing finish. wine Murças Terroir PVP 12,00€ MURÇAS RESERVA 2015- ESPORÃO MARGEM 2018- ESPORÃO (Douro) (Douro) GRAPES: Touriga Nacional, Touriga Franca GRAPES: Touriga Nacional, Touriga Franca, Sousão, COLOUR: Deep, with hints of violet. Tinta Amarela, Tinta Barroca, Tinta Roriz. AROMA: Very intense and exuberant, with ripe black fruits COLOUR: Deep dark and intense.. such as blackberry and blackcurrant standing out. AROMA: Complex, fresh and elegant aroma of dark berry PALATE: Concentrated and with good acidity, it has very fruits, with balsamic notes and integrated spicy notes from ripe tannins that give it a sense of volume and body. -

AN INTEGRATED COMMUNICATION PLAN for HERDADE DOS ARROCHAIS Raquel Rodrigues Antão Project Submitted As a Partial Requirement Fo

AN INTEGRATED COMMUNICATION PLAN FOR HERDADE DOS ARROCHAIS Raquel Rodrigues Antão Project submitted as a partial requirement for the conferral of Master in Marketing Supervisor Professor Doctor Hélia Gonçalves Pereira, Assistant Professor, ISCTE Business School, Marketing, Operations and Management Department April 2013 AN INTEGRATED COMMUNICATION PLAN FOR HERDADE DOS ARROCHAIS RESUMO A presente tese de mestrado é um projecto-empresa em cooperação com a Herdade dos Arrochais, uma empresa produtora de vinhos Alentejanos, com localização na Amareleja (Alentejo), cujo reconhecimento por parte dos consumidores é reduzido embora os seus vinhos tenham um grande potencial. Após a identificação do problema, foi analisada toda a envolvente macro-económica, o sector, a concorrência e o consumidor por forma a identificar as oportunidades existentes. Foi igualmente efetuada uma análise interna, que permitiu a identificação das principais lacunas da empresa, e uma revisão de literatura e uma revisão de literatura que permitiu enquadrar os principais conceitos teóricos que estão na base deste projeto. Apesar da atual crise económica, os portugueses continuam a ser dos maiores consumidores de vinho do Mundo, pelo que o problema que se verifica está relacionado com a falta de reconhecimento da marca. A solução encontrada para aumentar o valor e a notoriedade da marca, conquistando clientes e aumentando as vendas, foi um plano de comunicação integrada. Assim, foi elaborado um plano com especial enfoque na proposta de comunicação através da criação de um Website, com o intuito também de melhorar a distribuição. A proposta realizada resultou no desenvolvimento de ideias e ações, reforçando os principais pontos fortes encontrados e criando novas vantagens competitivas, sem esquecer as limitações monetárias da empresa, bem como a concorrência. -

INTERNATIONAL COMMERCIALIZATION STRATEGY: PORTUGUESE WINE in CHINA Ana Carolina Martins Mendes

INTERNATIONAL COMMERCIALIZATION STRATEGY: PORTUGUESE WINE IN CHINA Ana Carolina Martins Mendes Dissertation submitted as partial requirement for the conferral of Master of Science in Business Administration Supervisor: Dr. Nelson Campos Ramalho, Assistant Professor, ISCTE Business School May 2016 CHINA IN WINE PORTUGUESE Mendes Martins STRATEGY: Carolina Ana COMMERCIALIZATION INTERNATIONAL INTERNATIONAL COMMERCIALIZATION STRATEGY: PORTUGUESE WINE IN CHINA Ana Carolina Martins Mendes Dissertation submitted as partial requirement for the conferral of Master of Science in Business Administration Supervisor: Dr. Nelson Campos Ramalho, Assistant Professor, ISCTE Business School May 2016 Abstract Portugal's economy is strongly built upon wine industry with a per capita production and quality above average world indicators. Its sustainability and competitiveness depends on being able to grow alongside its competitors while looking attentively to emerging markets. China is one of the fastest growing economies in the world with the corresponding growth in wine consumption. Although China is one of the largest international trading countries with Portugal, and one of its biggest investors, the wine sector has been lagging, especially when compared with France or other wine producers. Considering its strategic importance it is mandatory that reasons be found to explain such fact with a focus on the Chinese opportunities in order to offer insights. Keywords: Competitive Advantage, Wine market, Internationalization, China JEL Classification: M16 International Business Administration, L1 Market Structure, Firm Strategy, and Market Performance, Q17 Agriculture in International Trade ii Resumo A economia portuguesa é fortemente influenciada e condicionada pela indústria do vinho, possuindo uma produção per capita e uma qualidade acima da média mundial. A sua sustentabilidade e competitividade dependem da capacidade de acompanhar o crescimento da concorrência, apostando nos mercados emergentes. -

Grape Escapes Brochure

Grape Escapes Short breaks and tours for wine lovers Love Wine…? So do we! Created by wine lovers for wine lovers, we are a small team of passionate and well-travelled people, who offer an inexhaustible selection of holidays to Europe’s premium wine regions. OUR MISSION: To provide high quality, good value holidays and tours in the premium wine regions of Europe by adopting a flexible, friendly and knowledgeable approach to the planning and delivery of every element of each trip. From our Premium tours as part of a small group in the world-famous regions of Champagne and Bordeaux, to exclusive birthday celebrations in Tuscany, and mouth-watering gastronomy experiences in Porto, our expertise lies in creating your perfect wine tasting trip. We would like to take this opportunity to thank our existing customers, for whom we have been delighted to arrange trips and whose feedback has been invaluable to us in perfecting the quality of our tours. A very large number of our customers return to us year on year and many more come through recommendations. The reason that we attract such loyalty from our customers is that not only do we provide an unforgettable trip; we also pride ourselves on giving superb customer service. This brochure is designed to provide you with information regarding our featured destinations and the types of experiences that we can arrange. Detailed descriptions of the multitude of packages that we offer can be found on our web site, www.grapeescapes.net and our handy Tour Finder allows you to browse all of the tours and filter them by wine colour, grape variety, country, region, price and duration. -

La Goya Manzanilla Sanlucar De Barrameda Spain 35/9 Alvear Fino

La Goya Manzanilla Sanlucar de Barrameda Spain 35/9 Alvear Fino en Rama Jerez Spain 50/10 Romate ‘NPU’ Amontillado Jerez Spain 11 Pennyweight ‘La Serena’ Oloroso Beechworth VIC 11 Romate ‘Regente’ Palo Cortado Jerez Spain 13 Napoleone & Co Pear Cider (330ml) Yarra Valley, VIC 8 Portica (White port,tonic & citrus) Porto Portugal 8 Escanciador Apple Sidra (250ml) Villaviciosa, Asturias Spain 7 Moritz Lager Barcelona Spain 8 Moritz ‘Epidor’ Barcelona Spain 10 Alhumbra Negra Granada Spain 10 Nastro Azzurro Peroni Italy 9 Mountain Goat ‘Steam Ale’ Melbourne 9 Cascade Light Tasmania 8 NV Vallformosa MVSA Macabeo/Parellada Penedes Spain 11 NV Paul Bara Pinot Noir/Chardonnay Bouzy France 18 2009 Belondrade ‘Apolonia’ Verdejo Castilla y leon Spain 11 2011 Chateau Petit Roubie Picpoul de Pinet Coteaux du Languedoc France 11 2009 Esporao Reserva Antao vaz/arinto/roupeiro Alentejo Portugal 14 2011 Pooley Pinot Grigio Coal River TAS 12 2011 Eidosela Albarino Rias Baixas Spain 13 2011 L’ Imposteur Grenache Gris/Roussanne Collioure France 15 2009 Tierra de Fernandez Gomez Garnacha Blanc Rioja Spain 12 2011 Espelt Lledoner Garnacha Emporda Spain 10 2011 Rayos Uva Tempranillo Rioja Spain 11 2009 Even Keel Shiraz Canberra ACT 12 2010 Ponce ‘La Casilla’ Bobal Manchuela Spain 11 2009 AN2 Callet/Montenegro/Syrah Mallorca 17 2009 Evohe ‘Vinas Viejas’ Garnacha Bajo Aragon Spain 10 2009 El Castro de Valtuille Mencia Bierzo Spain 10 2011 Allies ‘Main Ridge’ Pinot Noir Mornington Peninsula VIC 12 NV Vallformosa MVSA Macabeo/Parellada Penedes Spain 60 R & B Plageoles -

Wine by the Glass

Wine By the Glass Glass Bottle Sparkling and Champagne Zonin Prosecco 400 1,850 Glera Veneto, Italy Chandon Brut 750 3,500 Pinot Noir Chardonnay Victoria, Australia Gran Monte Crémant 750 3,500 Chenin Blanc Asoke Valley, Thailand Möet & Chandon Brut Impérial 1,300 6,000 Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, Pinot Meunier Épernay, France Rosé R de Roubine Rosé 600 2,250 Grenache, Shiraz, Cinsault Côtes de Provence, France Rates are inclusive of local tax & VAT, subject to 10% service charge Wine By the Glass Glass Bottle White Wine P. Ferraud & Fils 500 2,250 Sauvignon Blanc Pays d’Oc. France Château La Gravière 500 2,250 Semillon, Sauvignon Blanc Bordeaux, France Romio Friuli 350 1.500 Pinot Grigio Venezia, Italy Vina Maipo Vitral 350 1,500 Sauvignon Blanc Maipo Valley, Chile Round Hill Cellars 425 2,000 Chardonnay Napa Valley, USA Elderton E-Series Unoaked 375 1,800 Chardonnay Barossa Valley, Australia Pebble Lane 400 1,950 Sauvignon Blanc, Marlborough, New Zealand Gran Monte Spring 450 2,200 Chenin Blanc Asoke Valley, Thailand Rates are inclusive of local tax & VAT, subject to 10% service charge Wine By the Glass Glass Bottle Red Wine Château Cap de Fer 500 2,250 Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Cabernet Franc Bordeaux, France Robert Mondavi Woodbridge 450 1,950 Merlot California, USA Vina Maipo Vitral Reserva 350 1,500 Shiraz Maipo Valley, Chile Trapiche 400 1,800 Malbec Mendoza, Argentina Pebble Lane 400 1,800 Pinot Noir Marlborough , New Zealand Gran Monte Spring 450 2,200 Cabernet Sauvignon, Syrah Asoke Valley, Thailand Rates are inclusive of local -

The Role of Grapevine Leaf Morphoanatomical Traits in Determining Capacity for Coping with Abiotic Stresses: a Review

Ciência Téc. Vitiv. 36(01) 75-88. 2021 Review THE ROLE OF GRAPEVINE LEAF MORPHOANATOMICAL TRAITS IN DETERMINING CAPACITY FOR COPING WITH ABIOTIC STRESSES: A REVIEW CARACTERISTICAS MORFOANATÓMICAS DA FOLHA PARA A DETERMINAÇÃO DA CAPACIDADE DE ADAPTAÇÃO DA VIDEIRA AOS STRESSES ABIÓTICOS: REVISÃO Phoebe MacMillan1, Generosa Teixeira2,3, Carlos M. Lopes4, Ana Monteiro4,* 1 Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Tapada da Ajuda, 1349-017 Lisboa, Portugal. 2 cE3c, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa, edf. C2, Campo Grande, 1749-016, Lisboa, Portugal. 3 Faculdade de Farmácia, Universidade de Lisboa, Av. Prof. Gama Pinto, 1649-003 Lisboa, Portugal. 4 LEAF (Linking Landscape, Environment, Agriculture and Food), Dep. of Biosystems Science and Engineering, Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade de Lisboa, Tapada da Ajuda, 1349-017 Lisboa, Portugal. * Corresponding author: Tel.: + 351 918845993; e-mail: [email protected] (Received 15.03.2021. Accepted 31.05.2021) ABSTRACT Worldwide, there are thousands of Vitis vinifera grape cultivars used for wine production, creating a large morphological, anatomical, physiological and molecular diversity that needs to be further characterised and explored, with a focus on their capacity to withstand biotic and abiotic stresses. This knowledge can then be used to select better adapted genotypes in order to help face the challenges of the expected climate changes in the near future. It will also assist grape growers in choosing the most suitable cultivar(s) for each terroir; with adaptation to drought and heat stresses being a fundamental characteristic. The leaf blade of grapevines is the most exposed organ to abiotic stresses, therefore its study regarding the tolerance to water and heat stress is becoming particularly important, mainly in Mediterranean viticulture. -

Laying Down Detailed Rules for the Description and Presentation of Wines and Grape Musts

8 . 11 . 90 Official Journal of the European Communities No L 309 / 1 I (Acts whose publication is obligatory) COMMISSION REGULATION (EEC) No 3201 /90 of 16 October 1990 laying down detailed rules for the description and presentation of wines and grape musts THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, frequently been amended; whereas, in the interests of clarity, and on the occasion of further amendments, the rules in question should be consolidated; Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, Whereas, in applying rules concerning the description and presentation of wines, the traditional and customary practices of the Community wine-growing regions should Having regard to Council Regulation (EEC) No 822/ 87 of be taken into account to the extent that the traditional and 16 March 1987 on the common organization of the market customary practices are compatible with the principles of a in wine ( 3 ), as last amended by Regulation ( EEC) single market; whereas it is also necessary to avoid any No 1325 / 90 ( 2 ), and in particular Articles 72 ( 5 ) and 81 confusion in the use of expressions employed in labelling thereof, and to ensure that the information on the label is as clear and complete as possible for the consumer; Whereas Council Regulation ( EEC ) No 2392/ 89 (3 ), as amended by Regulation ( EEC ) No 3886 / 89 (4), lays down Whereas, in order to allow the bottler some freedom as general rules for the description and presentation of wines regards the manner in which he presents the mandatory and grape