Journal 26 2010 2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NR05 Oxford TWAO

OFFICIAL Rule 10(2)(d) Transport and Works Act 1992 The Transport and Works (Applications and Objections Procedure) (England and Wales) Rules 2006 Network Rail (Oxford Station Phase 2 Improvements (Land Only)) Order 202X Report summarising consultations undertaken 1 Introduction 1.1 Network Rail Infrastructure Limited ('Network Rail') is making an application to the Secretary of State for Transport for an order under the Transport and Works Act 1992. The proposed order is termed the Network Rail (Oxford Station Phase 2 Improvements (Land Only)) Order ('the Order'). 1.2 The purpose of the Order is to facilitate improved capacity and capability on the “Oxford Corridor” (Didcot North Junction to Aynho Junction) to meet the Strategic Business Plan objections for capacity enhancement and journey time improvements. As well as enhancements to rail infrastructure, improvements to highways are being undertaken as part of the works. Together, these form part of Oxford Station Phase 2 Improvements ('the Project'). 1.3 The Project forms part of a package of rail enhancement schemes which deliver significant economic and strategic benefits to the wider Oxford area and the country. The enhanced infrastructure in the Oxford area will provide benefits for both freight and passenger services, as well as enable further schemes in this strategically important rail corridor including the introduction of East West Rail services in 2024. 1.4 The works comprised in the Project can be summarised as follows: • Creation of a new ‘through platform’ with improved passenger facilities. • A new station entrance on the western side of the railway. • Replacement of Botley Road Bridge with improvements to the highway, cycle and footways. -

Strategic Review of Secondary Education Planning for Cheltenham

Strategic review of Secondary Education Planning for Cheltenham January 2017 1 Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................. 2 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Supporting data .................................................................................................................................. 3 Current number on roll ....................................................................................................................... 3 Pupil forecasts 2015/16 ...................................................................................................................... 4 Planned local housing developments ................................................................................................. 4 Strategic Housing ................................................................................................................................ 5 Recommendation, Land and Footnotes....………………………………………………………………………………………6 Executive Summary There has been pressure on local primary school places in Cheltenham since 2011. This is the result of a change in the birth rate locally and natural changing demographics, coupled with some local housing growth. This growth has been significant and resulted in the need to provide additional temporary and permanent school places at existing primary schools. -

Revised Lecture Programme 2020-21

November 2020 Cheltenham LHS For CONTENTS please see page 21 REVISED LECTURE PROGRAMME 2020-21 When we learned that severe restrictions would apply henceforth at St Luke’s Hall, and that the Borough Council was accepting no more bookings for the Council Chamber, we realised that our talks would have to go online. We are grateful that our lecturers are willing to adapt, and only sorry that not all mem- bers can participate. We have already delivered two lectures by Zoom. Those listed below will take us through until March, by which time - dare we hope? - there may be a prospect of meeting face to face once again. Newsletter No. 98 Affiliated to Cheltenham Arts Council November 2020 Registered Charity No. 1056046 Tuesday 8th December: http://www.cheltlocalhistory.org.uk Paul Barnett— The Cotswolds Navy: What’s in a Name? Land-locked as Gloucestershire is, with only the River Severn running gently EDITORIAL through its midst, this talk explores the region’s inseparable connection to the sea In this issue, another ‘Covid-era’ compi- via its maritime fleet of locally named vessels and the county’s contribution to lation, we again offer a variety of articles financing a depleted navy during Warship Week of 1942. we hope you will enjoy reading, There is also a bit of mental exercise in the form Tuesday 19th January 2021: of a little pictorial quiz—see page12-13. Martin Boothman and Peter Barlow—Early Gloucestershire Vehicle This picture is by way of a free sample. Registrations Do you know where it is? If you walk Peter Barlow and Martin Boothman, both Society members, will be talking about along Royal Well Place towards St how motor vehicle registration became compulsory country-wide with effect George’s Place you’ll see it there from 1st January 1904 and about their work in transcribing and indexing the (appropriately) on the side wall of the Gloucestershire vehicle registers from 1904 to the end of December 1913. -

Folktalk Issue 58

Issue 58 FOLKtalk Autumn 2018 Friends of Leckhampton Hill & Charlton Kings Common Conserving and improving the Hill for you Inside this issue: FOLK AGM 2 The Word from Wayne 13 Walter Ballinger: Stalwart and soldier 3 Who painted the trig point? 16 Cheltenham remembers 4 Aerial photos 17 The flora and fauna on the Hill 5 Smoke Signals 17 Work party report 10 STALWARTS REMEMBERED AT THE WHEATSHEAF On Sunday September 30th, in bright sunshine with a hint of an autumn breeze, a plaque to commemorate the so called Leckhampton Stalwarts was unveiled by Neela Mann at The Wheatsheaf in Old Bath Road. A gathering of more than 50 people heard Neela, a local history expert and a FOLK member, pay tribute to Walter Ballinger and the other Stalwarts, who were imprisoned in 1906 as a result of their action to secure public access to the Hill. The Wheatsheaf was the headquarters for the Stalwarts and so it is fitting that the new plaque will be a permanent reminder of the sacrifice they made so that future generations could continue to enjoy the Hill. The Leckhampton Local History Society organised the event with their members being half of the gathering. FOLK was well represented. Martin Horwood, Leckhampton ward Borough Councillor and a supporter of FOLK was present. The current owner of the Dale Forty Piano company, Colin Crawford attended the unveiling. Colin is not related to Henry Dale, who bought the site in 1894 and was a protagonist in the drama, but he has an interest in the history. Walkers along the Cotswold Way from Hartley Lane will be able to see another plaque dedicated to a Stalwart and more information on the battle for access is available on the FOLK website www.leckhamptonhill.org.uk/site- description/history. -

Painswick to Winchcombe Cycle Route

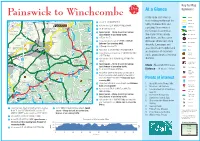

Great Comberton A4184 Elmley Castle B4035 Netherton B4632 B4081 Hinton on the Green Kersoe A38 CHIPPING CAMPDEN A46(T) Aston Somerville Uckinghall Broadway Ashton under Hill Kemerton A438 (T) M50 B4081 Wormington B4479 Laverton B4080 Beckford Blockley Ashchurch B4078 for Tewkesbury Bushley B4079 Great Washbourne Stanton A38 A38 Key to Map A417 TEWKESBURY A438 Alderton Snowshill Day A438 Bourton-on-the-Hill Symbols: B4079 A44 At a Glance M5 Teddington B4632 4 Stanway M50 B4208 Dymock Painswick to WinchcombeA424 Linkend Oxenton Didbrook A435 PH A hilly route from start to A Road Dixton Gretton Cutsdean Hailes B Road Kempley Deerhurst PH finish taking you through the Corse Ford 6 At fork TL SP BRIMPSFIELD. B4213 B4211 B4213 PH Gotherington Minor Road Tredington WINCHCOMBE Farmcote rolling Cotswold hills and Tirley PH 7 At T junctionB4077 TL SP BIRDLIP/CHELTENHAM. Botloe’s Green Apperley 6 7 8 9 10 Condicote Motorway Bishop’s Cleeve PH Several capturing the essence of Temple8 GuitingTR SP CIRENCESTER. Hardwicke 22 Lower Apperley Built-up Area Upleadon Haseld Coombe Hill the Cotswold countryside. Kineton9 Speed aware – Steep descent on narrow B4221 River Severn Orchard Nook PH Roundabouts A417 Gorsley A417 21 lane. Beware of oncoming traffic. The route follows mainly Newent A436 Kilcot A4091 Southam Barton Hartpury Ashleworth Boddington 10 At T junction TL. Lower Swell quiet lanes, and has some Railway Stations B4224 PH Guiting Power PH Charlton Abbots PH11 Cross over A 435 road SP UPPER COBERLEY. strenuous climbs and steep B4216 Prestbury Railway Lines Highleadon Extreme Care crossing A435. Aston Crews Staverton Hawling PH Upper Slaughter descents. -

Pates Grammar School

M1 Cheltenham - Charlton Kings - Moorend - Lansdown - Pates Grammar School Marchants Coaches Timetable valid from 02/09/2020 until further notice. Direction of stops: where shown (eg: W-bound) this is the compass direction towards which the bus is pointing when it stops Mondays to Fridays Service Restrictions Sch Cheltenham, after Beaufort Arms 0740 Charlton Kings, opp Six Ways Shops 0742 East End, corner of Chase Avenue 0746 Charlton Kings, by Spring Bridge 0747 Charlton Kings, opp Copt Elm Close 0749 Charlton Kings, after Post Office 0750 Charlton Kings, opp Sainsburys Local 0751 Moorend, by Branch Hill Rise 0752 Moorend, after Stockton Close 0753 Moorend, nr Sandy Lane 0754 Pilley, by Mead Road 0756 Charlton Park, opp Croquet Club 0757 Cheltenham, before Church of Latter-day Saints 0758 Cheltenham, by Suffolk Parade 0801 Cheltenham, opp Lansdown Walk 0803 Lansdown, by Cheltenham Spa Rail Stn 0806 Hester’s Way, o/s Pates Grammar School 0825 Saturdays Sundays Bank Holidays no service no service no service Service Restrictions: Sch - Gloucestershire School Days M1 Pates Grammar School - Lansdown - Moorend - Charlton Kings - Cheltenham Marchants Coaches Direction of stops: where shown (eg: W-bound) this is the compass direction towards which the bus is pointing when it stops Mondays to Fridays Service Restrictions Sch Hester’s Way, o/s Pates Grammar School 1555 Lansdown, opp Cheltenham Spa Rail Stn 1601 Cheltenham, nr Lansdown Walk 1603 Cheltenham, opp Suffolk Parade 1606 Cheltenham, after Church of Latter-day Saints 1609 Charlton Park, -

American and British Reactions to Mexico's Expropriation of Foreign Oil Properties, 1937-1943

THE DIPLOMACY OF EXPROPRIATION: AMERICAN AND BRITISH REACTIONS TO MEXICO'S EXPROPRIATION OF FOREIGN OIL PROPERTIES, 1937-1943 Catherine E. Jayne Submitted for the Degree of Ph.D., Arts Department of International History London School of Economics University of London November 1997 UMI Number: U111299 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U111299 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ^<3 32 S191 H S3S: 2 ABSTRACT On 18 March 1938 Mexican labour problems in the oil industry culminated in Mexican President Ldzaro Cdrdenas' decision to expropriate the holdings of 17 American, Dutch and British oil companies.^ The purpose of this thesis is to fill the gaps in the literature on the Mexican oil nationalisation by analyzing the policies of the oil companies, and comparing and analyzing in detail how policy was determined in both Britain and the United States at a time when Britain was trying to win US cooperation in the face of increasing hostilities in Europe and the Far East. While Whitehall wanted US cooperation in taking a firm stance against Mexico, Washington refused. -

Highways Information Pack

HIGHWAYS INFORMATION PACK June 2014 CHELTENHAM Produced by: Forward Programme Team Highways Commissioning Working together, improving the quality of life for Gloucestershire people Contents Foreword and introduction to Highways Information Pack Pointing you in the right direction 1 Area Highway Managers 2 Local Highway Managers - West 3 New Highways Contract - April 2014 4 Transport Asset Management Plan (TAMP) 5 Levels of Service (LoS) 6 Everything you wanted to know about potholes 9 Gloucestershire’s road condition 14 Winter Maintenance Service update (Salting) 18 Severe Weather Recovery Fund 20 The Big Community Offer: Highways - Your Way 21 Highways Local 22 Public Rights Of Way (PROW) 24 Capital Programme: Overview of programmes & budget allocation 26 Proposed Major Transport Schemes - Countywide 27 Improvements Programme 34 Road Programme 38 Footway Programme 45 Bridges & Structures Programme 48 Drainage Programme 52 Geotechnical Programme - Countywide 55 Street Lighting Programme - Countywide 60 Traffic Signals Programme - Countywide 63 Foreword and introduction to Highways Information Pack Welcome to the 2014 Highways Information Pack, so named because it gives you a pack of information related to our business and the services / programmes of work for the year ahead. Our works and services are based on the Transport Asset Management Plan that defines our strategy and levels of service in accordance with the Council’s Corporate Strategy and Local Transport Plan. The works we undertake are split into two types: Revenue and Capital. Generally revenue funding is used for the day-to-day operational repair of assets to keep the network safe and capital funding is used for the replacement of highway assets when they reach the end of their useful life as follows: Revenue Programme - operations and maintenance of the asset: Activities undertaken to ensure the efficient operation and serviceability of the asset, typically referred to as routine maintenance. -

Berky Enrichment Imaginative, Inspiring and Fun! Spring Concerts Berky Pupils Pull out All the Stops History Mystery Year 2 Solve Clues to Become Knights!

2019 SPRING MAGAZINE SCHOOL B ERKHAMPSTEAD TERM Berky enrichment IMAGINATIVE, INSPIRING AND FUN! Spring concerts BERKY PUPILS PULL OUT ALL THE STOPS History Mystery YEAR 2 SOLVE CLUES TO BECOME KNIGHTS! INSIDE: HELEN Gill’s BALLET CLASSES | CHESS SUCCESS | SPOTLIGHT ON CERYS MCCREANOR Thoughts from Spotlight on THE HEAD CERYS MCCREANOR Glance through this edition of the Berky Blazer and you’ll see evidence Mme McCreanor is our specialist language of creative teaching and a passion for learning... everywhere! teacher. She joined Berky in October 2016 and The staff offer such a wide range of wonderful opportunities for the teaches French to every pupil in the School. children... from the chicks in Kindergarten, to adventures in space in She also teaches Spanish to the Year 5s and 6s Reception, to Superheroes in Year 1, the wonderful History Mystery and manages to sneak in a few other languages Day in Year 2 with its code-breaking, research and sleuthing challenges on special days too. Mme McCreanor is a Year (and allowing me to dress up as King Richard). In Prep, the range of 3 form teacher, responsible for the U9 girls’ opportunities has included the annual 500 Word Story Competition, the games teams and also teaches mindfulness Commandery History trip, the House Pancake Races, football, netball and during Carousel. cross-country fixtures - as well as the very successful Chess fixtures and Here, some of her form ask the questions Congress and the wonderful Spring Concert. they’ve always wanted to know... Our magical Spring Concerts, held at the Pittville Pump Room, once Have you always been a teacher? again showed that Music is at the heart of Berkhampstead. -

Congress Report 2004

Congress Report 2004 The 136th annual Trades Union Congress 13-16 September, Brighton Contents Page General Council members 2004 – 2005-03-15………………………………..4 Section one - Congress decision…………………………………………...........7 Part 1 Resolutions carried.............................. ………………………………………………8 Part 2 Motion remitted………………………………………………… ............................30 Part 3 Motion Lost…………………………………………………….................................31 General Council statement on Europe………………………………….……. ......32 Section two – Verbatim report of Congress proceedings Day 1 Monday 13 September ......................................................................................34 Day 2 Tuesday 14 September……………………………………… .................................73 Day 3 Wednesday 15 September...............................................................................119 Day 4 Thursday 16 September ...................................................................................164 Section three - unions and their delegates ............................................187 Section four - details of past Congresses ...............................................197 Section five - General Council 1921 – 2004.............................................200 Index of speakers .........................................................................................205 3 General Council Members John Hannett 2004 – 2005 Union of Shop Distributive and Allied Workers Dave Anderson Pat Hawkes UNISON National Union of Teachers Jonathan Baume Billy Hayes FDA Communication -

Volume 02 Number 09

CAKE AND COCKHORSE Banbury Historical Society September 1964 2s.6d. BAN BURY HI ST OR1 C A L SOCIETY President: The Rt. Hon. Lord Saye and Sele. O.B.E.,M.C., D.L. Chairman: J.H. Fearon, Esq., Fleece Cottage, Bodicote, Banbury. Hon. Secretary Hon. Treasurer: J.S.W. Gibson+ F.S.G.. A.W. Pain, A.L.A. Humber House, c/o Borough Library, Bloxham. Marlborough Road, Banbuy. Banbury. (Tel: Bloxham 332) (Tel: Banbury 2282) Hon. Editor "Cake and Cockhorse": B. S. Trinder, 90 Bretch Hill. Banbury. Hon. Research Adviser: E.R.C. Brinkworth, M. A., F.R. HiSt. SOC. Hon. Archaelogical Adviser: J. H. Fearon, B.SC. Committee Members: Dr. C.F.C. Beeson. D.Sc., R.K. Bigwood. G.J.S. Ellacott, A.C.A. Dr. G.E. Gardam. Dr. H.G. Judge, M.A. *..*....tl The Society was founded in 1958 to encourage interest in the history of the town and neighbour- ing parts of Oxfordshire, Northamptonshire and Warwickshire. The magazine Cake and Cockhorse is issued to members four times a year. This includes illus- trated articles based on original local historical research, as well as recording the Society's activities. A booklet Old Banbury - a short popular history, by E.R.C. Brinkworth, M.A., price 3/6 and a pamphlet A History of Banbury Cross price 6d have been published and a Christmas card is a popular annual production, The Society also publishes an annual records volume. Banbury Marriage Register has been pub- lished in three parts, a volume on Oxfordshire Clockmakers 1400-1850 and South Newin ton Churchwardens' Accounts 1553-1684 have been produced and the Register oduials 'for Banbury covering the years 1558 - 1653 is planned for 1965. -

Economic Activity Draft 1.0

VCH Glos Cheltenham post-1945 – Economic Activity Draft 1.0 Economic Activity Jan Broadway In the immediate post-war period the economic strategy of Gloucestershire County Council was guided by the aims of safeguarding the aircraft industry workforce and encouraging the provision of jobs in the smaller towns and the Forest of Dean. There was consequently little provision for industrial development in Cheltenham, where the arrival of GCHQ, UCCA and Eagle Star increased the proportion of white-collar employment. There was also an emphasis on the town's development as a retail and tourism hub. At the end of the 20th century 28% of the town's economic output derived from the financial and business sectors, 20% from public administration, 18% from manufacturing, and 20% from distribution, hotels and catering. Its particular strengths were in tourism, shopping, education, construction and manufacturing.1 Manufacturing In 1946 a report by the county's former chief planning officer foresaw Cheltenham's future development as 'an industrial centre of no small importance'.2 However, as a result of its failure to acquire county borough status3, Cheltenham was obliged to follow the G.C.C. moratorium on new industrial development within the town.4 A 1947 survey of small, local firms found a majority in favour of moving to purpose-built, out-of-town facilities5, which of necessity would predominantly be built beyond the borough boundaries. In response to this the council purchased land across the borough border at the Runnings, Swindon for factory development.6