The Nature Restoration Trust: the First Five Years an Exploratory Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Change Assessment of Tolay Creek Restoration, San Pablo Bay

An Elevation and Climate Change Assessment of the Tolay Creek Restoration, San Pablo Bay National Wildlife Refuge U. S. Geological Survey, Western Ecological Research Center Data Summary Report Prepared for the California Landscape Conservation Cooperative and U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Refuges John Y. Takekawa, Karen M. Thorne, Kevin J. Buffington, and Chase M. Freeman Tolay Creek Restoration i An Elevation and Climate Change Assessment of the Tolay Creek Restoration, San Pablo Bay National Wildlife Refuge U.S. Geological Survey, Western Ecological Research Center Data Summary Report Prepared for California Landscape Conservation Cooperative and U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Refuges John Y. Takekawa, Karen M. Thorne, Kevin J. Buffington, and Chase M. Freeman 1 U.S. Geological Survey, Western Ecological Research Center, San Francisco Bay Estuary Field Station, 505 Azuar Drive Vallejo, CA 94592 USA 2 U.S. Geological Survey, Western Ecological Research Center, 3020 State University Dr. East, Modoc Hall Suite 2007, Sacramento, CA 95819 USA For more information contact: John Y. Takekawa, PhD Karen M. Thorne, PhD U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Western Ecological Research Center Western Ecological Research Center 505 Azuar Dr. 3020 State University Dr. East Vallejo, CA 94592 Modoc Hall, Suite 2007 Tel: (707) 562-2000 Sacramento, CA 95819 [email protected] Tel: (916)-278-9417 [email protected] Suggested Citation: Takekawa, J. Y., K. M. Thorne, K. J. Buffington, and C. M. Freeman. 2014. An elevation and climate change assessment of the Tolay Creek restoration, San Pablo Bay National Wildlife Refuge. Unpublished Data Summary Report. U. S. Geological Survey, Western Ecological Research Center, Vallejo, CA. -

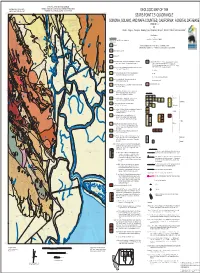

Sears Point Geologic

STATE OF CALIFORNIA- GRAY DAVIS, GOVERNOR CALIFORNIA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY THE RESOURCES AGENCY- MARY NICHOLS, SECRETARY FOR RESOURCES JAMES F. DAVIS, STATE GEOLOGIST DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION- DARRYL YOUNG, DIRECTOR GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE Qhf Qof QTu Qhf Qhty Qhly Qhc Qof Tsvm SEARS POINT 7.5' QUADRANGLE Qhf Qhc Qhty Qhc Qof Qhf Qof af QTu Qhc 30 Qhc 20 Tpu Qhf SONOMA, SOLANO, AND NAPA COUNTIES, CALIFORNIA: A DIGITAL DATABASE QTu Qof Th 35 Qhly af Qhty Qof Qha VERSION 1.0 1 Qhty Tpu Tp? By 50 Tsvm 20 Qf Qhbm 1 2 1 2 1 Qof David L. Wagner , Carolyn E. Randolph-Loar , Stephen P. Bezore , Robert C. Witter , and James Allen Tp? af Tsvm Tpu? Qof 49 1 Th 43 Qha Digital Database Qof Qha alf Qhbm 70 Unit Explanation by 1 1 55 Qhbm Jason D. Little and Victoria D. Walker Tsvm Qof (See Knudsen and others (2000), for more information on Qf 2002 30 Quaternary units). Tpu 40 Tp? Qhbm af Artificial fill Qhty Tpu Qhay afbm af 1. California Geological Survey, 801 K st. MS 12-31, Sacramento, CA 95814 Qof Qhbm 30 Qhf af Tsvt 2. William Lettis & Associates, Inc., 1777 Botello Drive, Suite 262 Walnut Creek, CA 94596 Tsvm Tsvm alf Tsvm Tsvm alf Qhbm afbm Artificial fill placed over bay mud 80 Tsvt? Tsvm Qhbm Qls Qhay 80 Qls Tsvt Qhbm Qhbm Qhbm Artificial levee fill Qhf alf 35 45 Tsvt Tsvt Tsvm 40 Tsvm Tsvt Qhbm Qhf 20 Qls Qhbm Qha af Qhc Late Holocene to modern (<150 years) stream channel deposits in active, natural KJfm Franciscan Complex melange. -

San Francisco Bay Plan

San Francisco Bay Plan San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission In memory of Senator J. Eugene McAteer, a leader in efforts to plan for the conservation of San Francisco Bay and the development of its shoreline. Photo Credits: Michael Bry: Inside front cover, facing Part I, facing Part II Richard Persoff: Facing Part III Rondal Partridge: Facing Part V, Inside back cover Mike Schweizer: Page 34 Port of Oakland: Page 11 Port of San Francisco: Page 68 Commission Staff: Facing Part IV, Page 59 Map Source: Tidal features, salt ponds, and other diked areas, derived from the EcoAtlas Version 1.0bc, 1996, San Francisco Estuary Institute. STATE OF CALIFORNIA GRAY DAVIS, Governor SAN FRANCISCO BAY CONSERVATION AND DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION 50 CALIFORNIA STREET, SUITE 2600 SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA 94111 PHONE: (415) 352-3600 January 2008 To the Citizens of the San Francisco Bay Region and Friends of San Francisco Bay Everywhere: The San Francisco Bay Plan was completed and adopted by the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission in 1968 and submitted to the California Legislature and Governor in January 1969. The Bay Plan was prepared by the Commission over a three-year period pursuant to the McAteer-Petris Act of 1965 which established the Commission as a temporary agency to prepare an enforceable plan to guide the future protection and use of San Francisco Bay and its shoreline. In 1969, the Legislature acted upon the Commission’s recommendations in the Bay Plan and revised the McAteer-Petris Act by designating the Commission as the agency responsible for maintaining and carrying out the provisions of the Act and the Bay Plan for the protection of the Bay and its great natural resources and the development of the Bay and shore- line to their highest potential with a minimum of Bay fill. -

Ethnohistory and Ethnogeography of the Coast Miwok and Their Neighbors, 1783-1840

ETHNOHISTORY AND ETHNOGEOGRAPHY OF THE COAST MIWOK AND THEIR NEIGHBORS, 1783-1840 by Randall Milliken Technical Paper presented to: National Park Service, Golden Gate NRA Cultural Resources and Museum Management Division Building 101, Fort Mason San Francisco, California Prepared by: Archaeological/Historical Consultants 609 Aileen Street Oakland, California 94609 June 2009 MANAGEMENT SUMMARY This report documents the locations of Spanish-contact period Coast Miwok regional and local communities in lands of present Marin and Sonoma counties, California. Furthermore, it documents previously unavailable information about those Coast Miwok communities as they struggled to survive and reform themselves within the context of the Franciscan missions between 1783 and 1840. Supplementary information is provided about neighboring Southern Pomo-speaking communities to the north during the same time period. The staff of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GGNRA) commissioned this study of the early native people of the Marin Peninsula upon recommendation from the report’s author. He had found that he was amassing a large amount of new information about the early Coast Miwoks at Mission Dolores in San Francisco while he was conducting a GGNRA-funded study of the Ramaytush Ohlone-speaking peoples of the San Francisco Peninsula. The original scope of work for this study called for the analysis and synthesis of sources identifying the Coast Miwok tribal communities that inhabited GGNRA parklands in Marin County prior to Spanish colonization. In addition, it asked for the documentation of cultural ties between those earlier native people and the members of the present-day community of Coast Miwok. The geographic area studied here reaches far to the north of GGNRA lands on the Marin Peninsula to encompass all lands inhabited by Coast Miwoks, as well as lands inhabited by Pomos who intermarried with them at Mission San Rafael. -

Species and Community Profiles to Six Clutches of Eggs, Totaling About 861 Eggs During California Vernal Pool Tadpole Her Lifetime (Ahl 1991)

3 Invertebrates their effects on this species are currently being investi- Franciscan Brine Shrimp gated (Maiss and Harding-Smith 1992). Artemia franciscana Kellogg Reproduction, Growth, and Development Invertebrates Brita C. Larsson Artemia franciscana has two types of reproduction, ovovi- General Information viparous and oviparous. In ovoviviparous reproduction, the fertilized eggs in a female can develop into free-swim- The Franciscan brine shrimp, Artemia franciscana (for- ming nauplii, which are set free by the mother. In ovipa- merly salina) (Bowen et al. 1985, Bowen and Sterling rous reproduction, however, the eggs, when reaching the 1978, Barigozzi 1974), is a small crustacean found in gastrula stage, become surrounded by a thick shell and highly saline ponds, lakes or sloughs that belong to the are deposited as cysts, which are in diapause (Sorgeloos order Anostraca (Eng et al. 1990, Pennak 1989). They 1980). In the Bay area, cysts production is generally are characterized by stalked compound eyes, an elongate highest during the fall and winter, when conditions for body, and no carapace. They have 11 pairs of swimming Artemia development are less favorable. The cysts may legs and the second antennae are uniramous, greatly en- persist for decades in a suspended state. Under natural larged and used as a clasping organ in males. The aver- conditions, the lifespan of Artemia is from 50 to 70 days. age length is 10 mm (Pennak 1989). Brine shrimp com- In the lab, females produced an average of 10 broods, monly swim with their ventral side upward. A. franciscana but the average under natural conditions may be closer lives in hypersaline water (70 to 200 ppt) (Maiss and to 3-4 broods, although this has not been confirmed. -

Environmental Assessment for Partial Funding for the Sears Point Restoration Project

Environmental Assessment For Partial Funding for the Sears Point Restoration Project September 2014 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Purpose and Need 1.2 Public Participation 1.3 Organization of this EA 2.0 PROPOSED ACTION 2.1 Alternatives Considered 3.0 AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT 3.1 Protected and Special-Status Species 3.1.1 Special Status Wildlife 3.1.2 Special Status Fish 3.2.3 Special Status Plants 3.2 Climate 4.0 ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS 4.1.1 Special Status Wildlife 4.1.2 Special Status Fish 4.1.3 Special Status Plants 4.2.1 Climate 5.0 MITIGATION MEASURES AND MONITORING 6.0 CUMULATIVE AND INDIRECT IMPACTS 6.1 Baseline Conditions for Cumulative Impacts Analysis 6.2 Past, Present, and Reasonably Foreseeable Future Actions 6.3 Resources Discussed and Geographic Study Areas 6.4 Approach to Cumulative Impact Analysis 7.0 AGENCY CONSULTATIONS 2 I. Executive Summary Ducks Unlimited requested funding through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Community-based Restoration Program (CRP) for restoration of a 960 acre site that is part of Sears Point Wetlands and Watershed Restoration Project . The Sonoma Land Trust (SLT), a non-profit organization, purchased the 2,327-acre properties collectively known as Sears Point in 2004 and 2005, and is the recipient of a number of grants for its restoration. In April of 2012, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the STL and the California Department of Fish and Game published a final Sears Point Wetland and Watershed Restoration Project Environmental Impact Report (SPWWRP) / Environmental Impact Statement that assess the environmental impacts of restoration of Sears Point (State Clearinghouse #2007102037). -

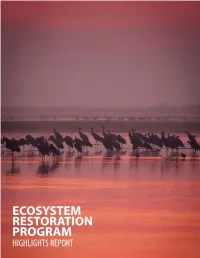

Ecosystem Restoration Program

ECOSYSTEM RESTORATION PROGRAM HIGHLIGHTS REPORT FOREWORD California’s Bay-Delta ecosystem is the largest estuary on the west coast of North America, draining almost 40,000 square miles via the state’s two largest rivers—the Sacramento and San Joaquin. The Bay-Delta ecosystem is home to hundreds of native fish, wildlife, and plant species, many of which are threatened or endangered. Since its inception in 1994 with the signing of the Bay-Delta Accord, the Ecosystem Restoration Program has been an unprecedented collaboration among local partners and governmental agencies to improve ecosystem processes and diverse habitats for species in the Bay-Delta watershed. Implemented by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, and the National Marine Fisheries Service, the primary focus of the Ecosystem Restoration Program is to increase the extent of aquatic and terrestrial habitats and improve ecological functions to support sustainable populations of native plant and animal species in the Bay-Delta ecosystem. Some of the Ecosystem Restoration Program’s accomplishments over the last two decades are highlighted here. FALL 2014 Front cover: Sandhill Cranes on Staten Island, Bay-Delta Region. Photo by B. Burkett. Back cover: Butte Creek Canyon, Sacramento Valley Region. Photo by T. McReynolds. TABLE OF CONTENTS FORWARD ERP STRATEGIC GOALS REGIONAL PERSPECTIVE MULTI-REGIONAL ACTIONS REGIONAL HIGHLIGHTS Sacramento Valley Region Clear Creek Bay-Delta Region Baylands Cosumnes River San Joaquin Valley Region -

NPDES Water Bodies

Attachment A: Detailed list of receiving water bodies within the Marin/Sonoma Mosquito Control District boundaries under the jurisdiction of Regional Water Quality Control Boards One and Two This list of watercourses in the San Francisco Bay Area groups rivers, creeks, sloughs, etc. according to the bodies of water they flow into. Tributaries are listed under the watercourses they feed, sorted by the elevation of the confluence so that tributaries entering nearest the sea appear they first. Numbers in parentheses are Geographic Nantes Information System feature ids. Watercourses which feed into the Pacific Ocean in Sonoma County north of Bodega Head, listed from north to south:W The Gualala River and its tributaries • Gualala River (253221): o North Fork (229679) - flows from Mendocino County. o South Fork (235010): Big Pepperwood Creek (219227) - flows from Mendocino County. • Rockpile Creek (231751) - flows from Mendocino County. Buckeye Creek (220029): Little Creek (227239) North Fork Buckeye Crcck (229647): Osser Creek (230143) • Roy Creek (231987) • Soda Springs Creek (234853) Wheatfield Fork (237594): Fuller Creek (223983): • Sullivan Crcck (235693) Boyd Creek (219738) • North Fork Fuller Creek (229676) South Fork Fuller Creek (235005) Haupt Creek (225023) • Tobacco Creek (236406) Elk Creek (223108) • )`louse Creek (225688): Soda Spring Creek (234845) Allen Creek (218142) Peppeawood Creek (230514): • Danfield Creek (222007): • Cow Creek (221691) • Jim Creek (226237) • Grasshopper Creek (224470) Britain Creek (219851) • Cedar Creek (220760) • Wolf Creek (238086) • Tombs Crock (236448) • Marshall Creek (228139): • McKenzie Creek (228391) Northern Sonoma Coast Watercourses which feed into the Pacific Ocean in Sonoma County between the Gualala and Russian Rivers, numbered from north to south: 1. -

Biological Resources Study Tolay Creek Ranch Sonoma County, California

BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES STUDY TOLAY CREEK RANCH SONOMA COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Submitted to: Sonoma Land Trust 2300 County Center Drive #120A Santa Rosa, California 95403 Prepared by: LSA Associates, Inc. 157 Park Place Point Richmond, California 94801 (510) 236-6810 LSA Project No. SOZ0801 May 2o, 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................................1 1.1 PURPOSE.............................................................................................................................1 1.2 LOCATION ..........................................................................................................................1 1.3 BACKGROUND ..................................................................................................................1 1.4 LAND USE AND HISTORY...............................................................................................2 1.5 REGULATORY CONTEXT................................................................................................3 1.5.1 Federal Endangered Species Act .............................................................................3 1.5.2 Clean Water Act ......................................................................................................4 1.5.3 Porter-Cologne Water Quality Control Act.............................................................5 1.5.4 Migratory Bird Treaty Act.......................................................................................5 -

DRAFT Sonoma Creek Watershed Enhancement Plan

DRAFT Sonoma Creek Watershed Enhancement Plan An owner’s manual for the residents & landowners of the Sonoma Creek Watershed. Prepared by: The Sonoma Resource Conservation District in conjunction with the people of the Sonoma Creek Watershed and collaboration with the Sonoma Ecology Center. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS .................................................................................................................................. 6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT .............................................................................................................. 8 SECTION 1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND.............................................................. 9 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................. 10 PURPOSE OF THE SONOMA CREEK WATERSHED ENHANCEMENT PLAN....................................... 10 PROCESS FOR DEVELOPING THE PLAN ........................................................................................ 10 STAKEHOLDER GROUPS ............................................................................................................. 11 ORGANIZATION OF THE PLAN ..................................................................................................... 14 WATERSHED GOALS ................................................................................................................... 15 CHAPTER 2: WATERSHED DESCRIPTION AND HISTORY ............................................... 18 WATERSHED BOUNDARY OVERVIEW ........................................................................................ -

Coastal Resilience Assessment of the San Francisco Bay and Outer Coast Watersheds

Coastal Resilience Assessment of the San Francisco Bay and Outer Coast Watersheds Suggested Citation: Crist, P.J., S. Veloz, J. Wood, R. White, M. Chesnutt, C. Scott, P. Cutter, and G. Dobson. Coastal Resilience Assessment of the San Francisco Bay and Outer Coast Watersheds. 2019. National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. IMPORTANT INFORMATION/DISCLAIMER: This report represents a Regional Coastal Resilience Assessment that can be used to identify places on the landscape for resilience-building efforts and conservation actions through understanding coastal flood threats, the exposure of populations and infrastructure have to those threats, and the presence of suitable fish and wildlife habitat. As with all remotely sensed or publicly available data, all features should be verified with a site visit, as the locations of suitable landscapes or areas containing flood hazards and community assets are approximate. The data, maps, and analysis provided should be used only as a screening-level resource to support management decisions. This report should be used strictly as a planning reference tool and not for permitting or other legal purposes. The scientific results and conclusions, as well as any views or opinions expressed herein, are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government, or the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation’s partners. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government or the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation or its funding sources. NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION DISCLAIMER: The scientific results and conclusions, as well as any views or opinions expressed herein, are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of NOAA or the Department of Commerce. -

Baseline Geomorphic Assessment of Tolay Creek, Sonoma, California

BASELINE GEOMORPHIC ASSESSMENT OF TOLAY CREEK SONOMA COUNTY, CALIFORNIA A REPORT PREPARED FOR SONOMA LAND TRUST Prepared by: Joan Florsheim, Geology Department University of California, Davis JUNE 2009 Florsheim 1 Tolay Creek Geomorphic Assessment Baseline Geomorphic Assessment of Tolay Creek INTRODUCTION This baseline geomorphic assessment of Tolay Creek Watershed is intended to provide information about geomorphology that may be used to aid Sonoma Land Trust to address active erosion and sedimentation processes. This information is treated within the context of natural processes, land use changes, and potential future restoration activities. In particular, this report addresses an important question: how do physical watershed characteristics and land uses govern geomorphic processes such as erosion and sedimentation in the Tolay Creek Watershed? This question is important to address due to concern that active gully and fluvial incision and bank erosion in the middle reaches of Tolay Creek and channel aggradation in downstream reaches occurred within the past decade. This work is based on a reconnaissance level investigation including field observations, map and photograph analysis, and discussions with agency staff and local residents knowledgeable about Tolay Creek. The data and results of the reconnaissance reported here is intended to provide a basis for an approach to restoration and management that accommodates geomorphic processes. Results also serve as a basis for a more detailed field work plan to initiate baseline monitoring that would be conducted during a future phase of this investigation. METHODS Methods utilized in this work included field reconnaissance, photographic analysis, historic, topographic, and geologic map analysis, review of available hydrologic, geologic, and geomorphic literature, and discussion with agency staff and residents knowledgeable about the watershed.