Baseline Geomorphic Assessment of Tolay Creek, Sonoma, California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Change Assessment of Tolay Creek Restoration, San Pablo Bay

An Elevation and Climate Change Assessment of the Tolay Creek Restoration, San Pablo Bay National Wildlife Refuge U. S. Geological Survey, Western Ecological Research Center Data Summary Report Prepared for the California Landscape Conservation Cooperative and U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Refuges John Y. Takekawa, Karen M. Thorne, Kevin J. Buffington, and Chase M. Freeman Tolay Creek Restoration i An Elevation and Climate Change Assessment of the Tolay Creek Restoration, San Pablo Bay National Wildlife Refuge U.S. Geological Survey, Western Ecological Research Center Data Summary Report Prepared for California Landscape Conservation Cooperative and U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Refuges John Y. Takekawa, Karen M. Thorne, Kevin J. Buffington, and Chase M. Freeman 1 U.S. Geological Survey, Western Ecological Research Center, San Francisco Bay Estuary Field Station, 505 Azuar Drive Vallejo, CA 94592 USA 2 U.S. Geological Survey, Western Ecological Research Center, 3020 State University Dr. East, Modoc Hall Suite 2007, Sacramento, CA 95819 USA For more information contact: John Y. Takekawa, PhD Karen M. Thorne, PhD U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Western Ecological Research Center Western Ecological Research Center 505 Azuar Dr. 3020 State University Dr. East Vallejo, CA 94592 Modoc Hall, Suite 2007 Tel: (707) 562-2000 Sacramento, CA 95819 [email protected] Tel: (916)-278-9417 [email protected] Suggested Citation: Takekawa, J. Y., K. M. Thorne, K. J. Buffington, and C. M. Freeman. 2014. An elevation and climate change assessment of the Tolay Creek restoration, San Pablo Bay National Wildlife Refuge. Unpublished Data Summary Report. U. S. Geological Survey, Western Ecological Research Center, Vallejo, CA. -

Bothin Marsh 46

EMERGENT ECOLOGIES OF THE BAY EDGE ADAPTATION TO CLIMATE CHANGE AND SEA LEVEL RISE CMG Summer Internship 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Research Introduction 2 Approach 2 What’s Out There Regional Map 6 Site Visits ` 9 Salt Marsh Section 11 Plant Community Profiles 13 What’s Changing AUTHORS Impacts of Sea Level Rise 24 Sarah Fitzgerald Marsh Migration Process 26 Jeff Milla Yutong Wu PROJECT TEAM What We Can Do Lauren Bergenholtz Ilia Savin Tactical Matrix 29 Julia Price Site Scale Analysis: Treasure Island 34 Nico Wright Site Scale Analysis: Bothin Marsh 46 This publication financed initiated, guided, and published under the direction of CMG Landscape Architecture. Conclusion Closing Statements 58 Unless specifically referenced all photographs and Acknowledgments 60 graphic work by authors. Bibliography 62 San Francisco, 2019. Cover photo: Pump station fronting Shorebird Marsh. Corte Madera, CA RESEARCH INTRODUCTION BREADTH As human-induced climate change accelerates and impacts regional map coastal ecologies, designers must anticipate fast-changing conditions, while design must adapt to and mitigate the effects of climate change. With this task in mind, this research project investigates the needs of existing plant communities in the San plant communities Francisco Bay, explores how ecological dynamics are changing, of the Bay Edge and ultimately proposes a toolkit of tactics that designers can use to inform site designs. DEPTH landscape tactics matrix two case studies: Treasure Island Bothin Marsh APPROACH Working across scales, we began our research with a broad suggesting design adaptations for Treasure Island and Bothin survey of the Bay’s ecological history and current habitat Marsh. -

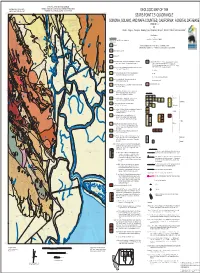

Sears Point Geologic

STATE OF CALIFORNIA- GRAY DAVIS, GOVERNOR CALIFORNIA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY THE RESOURCES AGENCY- MARY NICHOLS, SECRETARY FOR RESOURCES JAMES F. DAVIS, STATE GEOLOGIST DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION- DARRYL YOUNG, DIRECTOR GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE Qhf Qof QTu Qhf Qhty Qhly Qhc Qof Tsvm SEARS POINT 7.5' QUADRANGLE Qhf Qhc Qhty Qhc Qof Qhf Qof af QTu Qhc 30 Qhc 20 Tpu Qhf SONOMA, SOLANO, AND NAPA COUNTIES, CALIFORNIA: A DIGITAL DATABASE QTu Qof Th 35 Qhly af Qhty Qof Qha VERSION 1.0 1 Qhty Tpu Tp? By 50 Tsvm 20 Qf Qhbm 1 2 1 2 1 Qof David L. Wagner , Carolyn E. Randolph-Loar , Stephen P. Bezore , Robert C. Witter , and James Allen Tp? af Tsvm Tpu? Qof 49 1 Th 43 Qha Digital Database Qof Qha alf Qhbm 70 Unit Explanation by 1 1 55 Qhbm Jason D. Little and Victoria D. Walker Tsvm Qof (See Knudsen and others (2000), for more information on Qf 2002 30 Quaternary units). Tpu 40 Tp? Qhbm af Artificial fill Qhty Tpu Qhay afbm af 1. California Geological Survey, 801 K st. MS 12-31, Sacramento, CA 95814 Qof Qhbm 30 Qhf af Tsvt 2. William Lettis & Associates, Inc., 1777 Botello Drive, Suite 262 Walnut Creek, CA 94596 Tsvm Tsvm alf Tsvm Tsvm alf Qhbm afbm Artificial fill placed over bay mud 80 Tsvt? Tsvm Qhbm Qls Qhay 80 Qls Tsvt Qhbm Qhbm Qhbm Artificial levee fill Qhf alf 35 45 Tsvt Tsvt Tsvm 40 Tsvm Tsvt Qhbm Qhf 20 Qls Qhbm Qha af Qhc Late Holocene to modern (<150 years) stream channel deposits in active, natural KJfm Franciscan Complex melange. -

San Francisco Bay Plan

San Francisco Bay Plan San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission In memory of Senator J. Eugene McAteer, a leader in efforts to plan for the conservation of San Francisco Bay and the development of its shoreline. Photo Credits: Michael Bry: Inside front cover, facing Part I, facing Part II Richard Persoff: Facing Part III Rondal Partridge: Facing Part V, Inside back cover Mike Schweizer: Page 34 Port of Oakland: Page 11 Port of San Francisco: Page 68 Commission Staff: Facing Part IV, Page 59 Map Source: Tidal features, salt ponds, and other diked areas, derived from the EcoAtlas Version 1.0bc, 1996, San Francisco Estuary Institute. STATE OF CALIFORNIA GRAY DAVIS, Governor SAN FRANCISCO BAY CONSERVATION AND DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION 50 CALIFORNIA STREET, SUITE 2600 SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA 94111 PHONE: (415) 352-3600 January 2008 To the Citizens of the San Francisco Bay Region and Friends of San Francisco Bay Everywhere: The San Francisco Bay Plan was completed and adopted by the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission in 1968 and submitted to the California Legislature and Governor in January 1969. The Bay Plan was prepared by the Commission over a three-year period pursuant to the McAteer-Petris Act of 1965 which established the Commission as a temporary agency to prepare an enforceable plan to guide the future protection and use of San Francisco Bay and its shoreline. In 1969, the Legislature acted upon the Commission’s recommendations in the Bay Plan and revised the McAteer-Petris Act by designating the Commission as the agency responsible for maintaining and carrying out the provisions of the Act and the Bay Plan for the protection of the Bay and its great natural resources and the development of the Bay and shore- line to their highest potential with a minimum of Bay fill. -

Ethnohistory and Ethnogeography of the Coast Miwok and Their Neighbors, 1783-1840

ETHNOHISTORY AND ETHNOGEOGRAPHY OF THE COAST MIWOK AND THEIR NEIGHBORS, 1783-1840 by Randall Milliken Technical Paper presented to: National Park Service, Golden Gate NRA Cultural Resources and Museum Management Division Building 101, Fort Mason San Francisco, California Prepared by: Archaeological/Historical Consultants 609 Aileen Street Oakland, California 94609 June 2009 MANAGEMENT SUMMARY This report documents the locations of Spanish-contact period Coast Miwok regional and local communities in lands of present Marin and Sonoma counties, California. Furthermore, it documents previously unavailable information about those Coast Miwok communities as they struggled to survive and reform themselves within the context of the Franciscan missions between 1783 and 1840. Supplementary information is provided about neighboring Southern Pomo-speaking communities to the north during the same time period. The staff of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GGNRA) commissioned this study of the early native people of the Marin Peninsula upon recommendation from the report’s author. He had found that he was amassing a large amount of new information about the early Coast Miwoks at Mission Dolores in San Francisco while he was conducting a GGNRA-funded study of the Ramaytush Ohlone-speaking peoples of the San Francisco Peninsula. The original scope of work for this study called for the analysis and synthesis of sources identifying the Coast Miwok tribal communities that inhabited GGNRA parklands in Marin County prior to Spanish colonization. In addition, it asked for the documentation of cultural ties between those earlier native people and the members of the present-day community of Coast Miwok. The geographic area studied here reaches far to the north of GGNRA lands on the Marin Peninsula to encompass all lands inhabited by Coast Miwoks, as well as lands inhabited by Pomos who intermarried with them at Mission San Rafael. -

Species and Community Profiles to Six Clutches of Eggs, Totaling About 861 Eggs During California Vernal Pool Tadpole Her Lifetime (Ahl 1991)

3 Invertebrates their effects on this species are currently being investi- Franciscan Brine Shrimp gated (Maiss and Harding-Smith 1992). Artemia franciscana Kellogg Reproduction, Growth, and Development Invertebrates Brita C. Larsson Artemia franciscana has two types of reproduction, ovovi- General Information viparous and oviparous. In ovoviviparous reproduction, the fertilized eggs in a female can develop into free-swim- The Franciscan brine shrimp, Artemia franciscana (for- ming nauplii, which are set free by the mother. In ovipa- merly salina) (Bowen et al. 1985, Bowen and Sterling rous reproduction, however, the eggs, when reaching the 1978, Barigozzi 1974), is a small crustacean found in gastrula stage, become surrounded by a thick shell and highly saline ponds, lakes or sloughs that belong to the are deposited as cysts, which are in diapause (Sorgeloos order Anostraca (Eng et al. 1990, Pennak 1989). They 1980). In the Bay area, cysts production is generally are characterized by stalked compound eyes, an elongate highest during the fall and winter, when conditions for body, and no carapace. They have 11 pairs of swimming Artemia development are less favorable. The cysts may legs and the second antennae are uniramous, greatly en- persist for decades in a suspended state. Under natural larged and used as a clasping organ in males. The aver- conditions, the lifespan of Artemia is from 50 to 70 days. age length is 10 mm (Pennak 1989). Brine shrimp com- In the lab, females produced an average of 10 broods, monly swim with their ventral side upward. A. franciscana but the average under natural conditions may be closer lives in hypersaline water (70 to 200 ppt) (Maiss and to 3-4 broods, although this has not been confirmed. -

Environmental Assessment for Partial Funding for the Sears Point Restoration Project

Environmental Assessment For Partial Funding for the Sears Point Restoration Project September 2014 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Purpose and Need 1.2 Public Participation 1.3 Organization of this EA 2.0 PROPOSED ACTION 2.1 Alternatives Considered 3.0 AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT 3.1 Protected and Special-Status Species 3.1.1 Special Status Wildlife 3.1.2 Special Status Fish 3.2.3 Special Status Plants 3.2 Climate 4.0 ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS 4.1.1 Special Status Wildlife 4.1.2 Special Status Fish 4.1.3 Special Status Plants 4.2.1 Climate 5.0 MITIGATION MEASURES AND MONITORING 6.0 CUMULATIVE AND INDIRECT IMPACTS 6.1 Baseline Conditions for Cumulative Impacts Analysis 6.2 Past, Present, and Reasonably Foreseeable Future Actions 6.3 Resources Discussed and Geographic Study Areas 6.4 Approach to Cumulative Impact Analysis 7.0 AGENCY CONSULTATIONS 2 I. Executive Summary Ducks Unlimited requested funding through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Community-based Restoration Program (CRP) for restoration of a 960 acre site that is part of Sears Point Wetlands and Watershed Restoration Project . The Sonoma Land Trust (SLT), a non-profit organization, purchased the 2,327-acre properties collectively known as Sears Point in 2004 and 2005, and is the recipient of a number of grants for its restoration. In April of 2012, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the STL and the California Department of Fish and Game published a final Sears Point Wetland and Watershed Restoration Project Environmental Impact Report (SPWWRP) / Environmental Impact Statement that assess the environmental impacts of restoration of Sears Point (State Clearinghouse #2007102037). -

Petaluma Watershed Science and Ecosystem Restoration Project Project Information

Petaluma Watershed Science and Ecosystem Restoration Project Project Information 1. Proposal Title: Petaluma Watershed Science and Ecosystem Restoration Project 2. Proposal applicants: Leandra Swent, Southern Sonoma County Resource Conservation District Nadav Nur, Point Reyes Bird Observatory Laurel Collins, Geomorphology Consultant 3. Corresponding Contact Person: Leandra Swent Southern Sonoma County Resource Conservation District 1301 Redwood Way, Suite 170 Petaluma, CA 94954 707 794-1242 [email protected] 4. Project Keywords: Geomorphology Habitat Restoration, Riparian Saline-freshwater Interfaces 5. Type of project: Implementation_Pilot 6. Does the project involve land acquisition, either in fee or through a conservation easement? No 7. Topic Area: Riparian Habitat 8. Type of applicant: Local Agency 9. Location - GIS coordinates: Latitude: 38.071 Longitude: -122.374 Datum: NAD83 Describe project location using information such as water bodies, river miles, road intersections, landmarks, and size in acres. The Petaluma River is located in southern Sonoma County and a portion of northeastern Marin County. It drains a 146 square mile, pear shaped basin. The Petaluma River empties into the northwest portion of San Pablo Bay. The largest sub-watershed is San Antonio Creek located in the western portion of the watershed, south of the community of Petaluma. It flows from near Laguna Lake in Chileno Valley to the Petaluma marsh and divides Marin and Sonoma Counties. U.S. Highway 101 bisects the watershed nearly in half, trending north-south. The watershed is approximately 19 miles long and 13 miles wide with the City of Petaluma near its center. 10. Location - Ecozone: 2.4 Petaluma River, 2.5 San Pablo Bay 11. -

Abundance and Distribution of Shorebirds in the San Francisco Bay Area

WESTERN BIRDS Volume 33, Number 2, 2002 ABUNDANCE AND DISTRIBUTION OF SHOREBIRDS IN THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY AREA LYNNE E. STENZEL, CATHERINE M. HICKEY, JANET E. KJELMYR, and GARY W. PAGE, Point ReyesBird Observatory,4990 ShorelineHighway, Stinson Beach, California 94970 ABSTRACT: On 13 comprehensivecensuses of the San Francisco-SanPablo Bay estuaryand associatedwetlands we counted325,000-396,000 shorebirds (Charadrii)from mid-Augustto mid-September(fall) and in November(early winter), 225,000 from late Januaryto February(late winter); and 589,000-932,000 in late April (spring).Twenty-three of the 38 speciesoccurred on all fall, earlywinter, and springcounts. Median counts in one or moreseasons exceeded 10,000 for 10 of the 23 species,were 1,000-10,000 for 4 of the species,and were less than 1,000 for 9 of the species.On risingtides, while tidal fiats were exposed,those fiats held the majorityof individualsof 12 speciesgroups (encompassing 19 species);salt ponds usuallyheld the majorityof 5 speciesgroups (encompassing 7 species); 1 specieswas primarilyon tidal fiatsand in other wetlandtypes. Most speciesgroups tended to concentratein greaterproportion, relative to the extent of tidal fiat, either in the geographiccenter of the estuaryor in the southernregions of the bay. Shorebirds' densitiesvaried among 14 divisionsof the unvegetatedtidal fiats. Most species groups occurredconsistently in higherdensities in someareas than in others;however, most tidalfiats held relativelyhigh densitiesfor at leastone speciesgroup in at leastone season.Areas supportingthe highesttotal shorebirddensities were also the ones supportinghighest total shorebird biomass, another measure of overallshorebird use. Tidalfiats distinguished most frequenfiy by highdensities or biomasswere on the east sideof centralSan FranciscoBay andadjacent to the activesalt ponds on the eastand southshores of southSan FranciscoBay and alongthe Napa River,which flowsinto San Pablo Bay. -

3.2 Planning Area Description, Map and Boundaries

3.2 Planning Area Description Southern Sonoma County SWRP/Sonoma County Water Agency 3.2 Planning Area Description, Map and Boundaries Justification of Planning Area Boundaries The planning area addressed by the Southern Sonoma Storm Water Resource Plan will include the watersheds of two neighboring tributaries to San Pablo Bay: Petaluma River and Sonoma Creek (see Figure 1). These two watersheds are well suited for coverage under a single comprehensive Storm Water Resource Plan (SWRP) because they are substantially identical to the jurisdictional areas of Sonoma County which drain into San Pablo Bay and the larger San Francisco Bay and share water quality goals driven by similar impairments in shared receiving waters. Petaluma and Sonoma watersheds also share similar and consistent typified land uses and flooding patterns that generate collaboration across watersheds. The Southern Sonoma County SWRP uses the CalWater 2.2 Hydrologic Area delineation for both watersheds in order to utilize the vast amount of existing data to support the project prioritization and quantification process. Supporting documents to be referenced within this plan have used this boundary for justification as have existing and original data sets and spatial layers. Concurrent planning efforts in the County, including the future Groundwater Sustainability Plans, pursuant to Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) and the Sonoma County Agricultural Preservation and Open Space District’s (SCAPOSDs) Vital Lands Initiative, will utilize the same planning area boundary allowing collaborators to maintain consistency between regional efforts to promote land use planning and storm water management objectives, as well as potential opportunities for recharge. The hydrologic area scale was used for both watersheds as limited existing data was found through an initial analysis that would provide a comprehensive look at smaller cataloging units. -

12 Hydrology, Flooding and Water Quality

12 HYDROLOGY, FLOODING AND WATER QUALITY This chapter describes local and regional hydrology, flooding and water quality in and around Novato, as well as the applicable federal, State and local regulations. A. Regulatory Framework 1. Federal Regulations a. Federal Water Pollution Control Act The Federal Water Pollution Control Act (Clean Water Act), also known as the CWA, was enacted in 1972 to restore and maintain the chemical, physical and biological integrity of the waters of the United States. The two-phase National Stormwater Program was established as part of the CWA. Phase 1 of the program requires discharges from Municipal Separate Storm Sewer Systems (MS4s) serving over 100,000 people to be covered under a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit. The City of Novato is considered a permittee under California’s statewide general permit (Water Quality Order No. 2003-0005-DWQ) for MS4s. Permitees must develop and implement a Stormwater Management Plan (SWMP) with the goal of reducing discharged pollutants to the maxi- mum extent. The City of Novato’s NPDES Storm Water Program prevents illicit discharges into drains, waterways and wetlands, and is discussed in more detail in Chapter 16, Utilities. b. National Flood Insurance Program Congress passed the National Flood Insurance Act of 1968 and the Flood Disaster Protection Act of 1973 to address the increasing cost of flood-related disaster relief. The intent of National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) is to reduce the need for large, publicly-funded flood control structures and disaster relief by restricting development on floodplains. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) administers the NFIP to provide subsidized flood insurance to communities that comply with FEMA regulations and limit development on floodplains. -

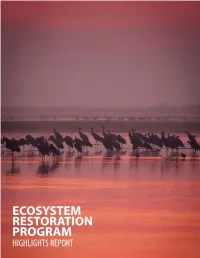

Ecosystem Restoration Program

ECOSYSTEM RESTORATION PROGRAM HIGHLIGHTS REPORT FOREWORD California’s Bay-Delta ecosystem is the largest estuary on the west coast of North America, draining almost 40,000 square miles via the state’s two largest rivers—the Sacramento and San Joaquin. The Bay-Delta ecosystem is home to hundreds of native fish, wildlife, and plant species, many of which are threatened or endangered. Since its inception in 1994 with the signing of the Bay-Delta Accord, the Ecosystem Restoration Program has been an unprecedented collaboration among local partners and governmental agencies to improve ecosystem processes and diverse habitats for species in the Bay-Delta watershed. Implemented by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, and the National Marine Fisheries Service, the primary focus of the Ecosystem Restoration Program is to increase the extent of aquatic and terrestrial habitats and improve ecological functions to support sustainable populations of native plant and animal species in the Bay-Delta ecosystem. Some of the Ecosystem Restoration Program’s accomplishments over the last two decades are highlighted here. FALL 2014 Front cover: Sandhill Cranes on Staten Island, Bay-Delta Region. Photo by B. Burkett. Back cover: Butte Creek Canyon, Sacramento Valley Region. Photo by T. McReynolds. TABLE OF CONTENTS FORWARD ERP STRATEGIC GOALS REGIONAL PERSPECTIVE MULTI-REGIONAL ACTIONS REGIONAL HIGHLIGHTS Sacramento Valley Region Clear Creek Bay-Delta Region Baylands Cosumnes River San Joaquin Valley Region