Indigenous Archaeology at Tolay Lake

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Change Assessment of Tolay Creek Restoration, San Pablo Bay

An Elevation and Climate Change Assessment of the Tolay Creek Restoration, San Pablo Bay National Wildlife Refuge U. S. Geological Survey, Western Ecological Research Center Data Summary Report Prepared for the California Landscape Conservation Cooperative and U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Refuges John Y. Takekawa, Karen M. Thorne, Kevin J. Buffington, and Chase M. Freeman Tolay Creek Restoration i An Elevation and Climate Change Assessment of the Tolay Creek Restoration, San Pablo Bay National Wildlife Refuge U.S. Geological Survey, Western Ecological Research Center Data Summary Report Prepared for California Landscape Conservation Cooperative and U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Refuges John Y. Takekawa, Karen M. Thorne, Kevin J. Buffington, and Chase M. Freeman 1 U.S. Geological Survey, Western Ecological Research Center, San Francisco Bay Estuary Field Station, 505 Azuar Drive Vallejo, CA 94592 USA 2 U.S. Geological Survey, Western Ecological Research Center, 3020 State University Dr. East, Modoc Hall Suite 2007, Sacramento, CA 95819 USA For more information contact: John Y. Takekawa, PhD Karen M. Thorne, PhD U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Western Ecological Research Center Western Ecological Research Center 505 Azuar Dr. 3020 State University Dr. East Vallejo, CA 94592 Modoc Hall, Suite 2007 Tel: (707) 562-2000 Sacramento, CA 95819 [email protected] Tel: (916)-278-9417 [email protected] Suggested Citation: Takekawa, J. Y., K. M. Thorne, K. J. Buffington, and C. M. Freeman. 2014. An elevation and climate change assessment of the Tolay Creek restoration, San Pablo Bay National Wildlife Refuge. Unpublished Data Summary Report. U. S. Geological Survey, Western Ecological Research Center, Vallejo, CA. -

Issue Information

Juengst and Becker, Editors Editors and Becker, Juengst of Community The Bioarchaeology 28 AP3A No. The Bioarchaeology of Community Sara L. Juengst and Sara K. Becker, Editors Contributions by Sara K. Becker Deborah Blom Jered B. Cornelison Sylvia Deskaj Lynne Goldstein Sara L. Juengst Ann M. Kakaliouras Wendy Lackey-Cornelison William J. Meyer Anna C. Novotny Molly K. Zuckerman 2017 Archeological Papers of the ISSN 1551-823X American Anthropological Association, Number 28 aapaa_28_1_cover.inddpaa_28_1_cover.indd 1 112/05/172/05/17 22:26:26 PPMM The Bioarchaeology of Community Sara L. Juengst and Sara K. Becker, Editors Contributions by Sara K. Becker Deborah Blom Jered B. Cornelison Sylvia Deskaj Lynne Goldstein Sara L. Juengst Ann M. Kakaliouras Wendy Lackey-Cornelison William J. Meyer Anna C. Novotny Molly K. Zuckerman 2017 Archeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association, Number 28 ARCHEOLOGICAL PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION Lynne Goldstein, General Series Editor Number 28 THE BIOARCHAEOLOGY OF COMMUNITY 2017 Aims and Scope: The Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association (AP3A) is published on behalf of the Archaeological Division of the American Anthropological Association. AP3A publishes original monograph-length manuscripts on a wide range of subjects generally considered to fall within the purview of anthropological archaeology. There are no geographical, temporal, or topical restrictions. Organizers of AAA symposia are particularly encouraged to submit manuscripts, but submissions need not be restricted to these or other collected works. Copyright and Copying (in any format): © 2017 American Anthropological Association. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing from the copyright holder. -

A Homestead Era History of Nunns' Canyon and Calabazas Creek

A Homestead Era History of Nunns’ Canyon and Calabazas Creek Preserve c.1850 - 1910 Glen Ellen, California BASELINE CONSULTING contents Homesteads, Roads, & Land Ownership 3 Historical Narrative 4 Introduction Before 1850 American Era Timeline 18 Selected Maps & documents 24 Sources 29 Notes on the Approach 32 and focus of this study Note: Historically, what is now Calabazas Creek Preserve was referred to as Nunns’ Can- yon. These designations are used interchangeably in this report and refer to all former public lands of the United States within the boundaries of the Preserve. Copyright © 013, Baseline Consulting. Researched, compiled and presented by Arthur Dawson. Right to reproduce granted to Lauren Johannessen and the Sonoma County Agricultural Preservation and Open Space District Special thanks to Lauren Johannessen, who initially commissioned this effort.Also to the Sonoma County Agricultural Preservation and Open Space District for additional support. DISCLAIMER: While every effort has been made to be accurate, further research may bring to light additional information. Baseline Consulting guarantees that the sources used for this history contain the stated facts; however some speculation was involved in developing this report. For inquiries about this report, services offered by Baseline Consulting, or permission to reproduce this report in whole or in part, contact: BASELINE CONSULTING ESSENTIAL INFORMATION FOR LANDOWNERS & RESOURCE MANAGERS P.O. Box 207 13750 Arnold Drive, Suite 3 Glen Ellen, California 95442 (707) 996-9967 (707) 509-9427 [email protected] www.baselineconsult.com A HOMESTEAD ERA HISTORY OF NUNNS’ CANYON & CALABAZAS CREEK PRESERVE Baseline Consulting A HOMESTEAD ERA HISTORY OF NUNNS’ CANYON & CALABAZAS CREEK PRESERVE Baseline Consulting 3 HISTORICAL narratiVE Introduction Time has erased much of the story of Nunns’ Canyon homesteaders. -

Historic Context Statement City of Benicia February 2011 Benicia, CA

Historic Context Statement City of Benicia February 2011 Benicia, CA Prepared for City of Benicia Department of Public Works & Community Development Prepared by page & turnbull, inc. 1000 Sansome Street, Ste. 200, San Francisco CA 94111 415.362.5154 / www.page-turnbull.com Benicia Historic Context Statement FOREWORD “Benicia is a very pretty place; the situation is well chosen, the land gradually sloping back from the water, with ample space for the spread of the town. The anchorage is excellent, vessels of the largest size being able to tie so near shore as to land goods without lightering. The back country, including the Napa and Sonoma Valleys, is one of the finest agriculture districts in California. Notwithstanding these advantages, Benicia must always remain inferior in commercial advantages, both to San Francisco and Sacramento City.”1 So wrote Bayard Taylor in 1850, less than three years after Benicia’s founding, and another three years before the city would—at least briefly—serve as the capital of California. In the century that followed, Taylor’s assessment was echoed by many authors—that although Benicia had all the ingredients for a great metropolis, it was destined to remain in the shadow of others. Yet these assessments only tell a half truth. While Benicia never became the great commercial center envisioned by its founders, its role in Northern California history is nevertheless one that far outstrips the scale of its geography or the number of its citizens. Benicia gave rise to the first large industrial works in California, hosted the largest train ferries ever constructed, and housed the West Coast’s primary ordnance facility for over 100 years. -

Southern Sonoma County Stormwater Resources Plan Evaluation Process

Appendix A List of Stakeholders Engaged APPENDIX A List of Stakeholders Engaged Specific audiences engaged in the planning process are identified below. These audiences include: cities, government officials, landowners, public land managers, locally regulated commercial, agricultural and industrial stakeholders, non-governmental organizations, mosquito and vector control districts and the general public. TABLE 1 LIST OF STAKEHOLDERS ENGAGED Organization Type Watershed 1st District Supervisor Government Sonoma 5th District Supervisor Government Petaluma City of Petaluma Government Petaluma City of Sonoma Government Sonoma Daily Acts Non-Governmental Petaluma Friends of the Petaluma River Non-Governmental Petaluma Zone 2A Petaluma River Watershed- Flood Control Government Petaluma Advisory Committee Zone 3A Valley of the Moon - Flood Control Advisory Government Sonoma Committee Marin Sonoma Mosquito & Vector Control District Special District Both Sonoma Ecology Center Non-Governmental Sonoma Sonoma County Regional Parks Government Both Sonoma County Agricultural Preservation and Open Government Both Space District Sonoma Land Trust Non-Governmental Both Sonoma County Transportation and Public Works Government Both Valley of the Moon Water District Government Sonoma Sonoma Resource Conservation District Special District Both Sonoma County Permit Sonoma Government Both Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Non-Governmental N/A California State Parks Government Both California State Water Resources Control Board Government N/A Southern Sonoma -

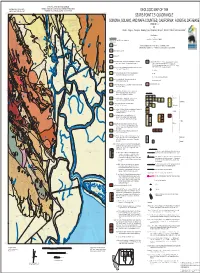

Sears Point Geologic

STATE OF CALIFORNIA- GRAY DAVIS, GOVERNOR CALIFORNIA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY THE RESOURCES AGENCY- MARY NICHOLS, SECRETARY FOR RESOURCES JAMES F. DAVIS, STATE GEOLOGIST DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION- DARRYL YOUNG, DIRECTOR GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE Qhf Qof QTu Qhf Qhty Qhly Qhc Qof Tsvm SEARS POINT 7.5' QUADRANGLE Qhf Qhc Qhty Qhc Qof Qhf Qof af QTu Qhc 30 Qhc 20 Tpu Qhf SONOMA, SOLANO, AND NAPA COUNTIES, CALIFORNIA: A DIGITAL DATABASE QTu Qof Th 35 Qhly af Qhty Qof Qha VERSION 1.0 1 Qhty Tpu Tp? By 50 Tsvm 20 Qf Qhbm 1 2 1 2 1 Qof David L. Wagner , Carolyn E. Randolph-Loar , Stephen P. Bezore , Robert C. Witter , and James Allen Tp? af Tsvm Tpu? Qof 49 1 Th 43 Qha Digital Database Qof Qha alf Qhbm 70 Unit Explanation by 1 1 55 Qhbm Jason D. Little and Victoria D. Walker Tsvm Qof (See Knudsen and others (2000), for more information on Qf 2002 30 Quaternary units). Tpu 40 Tp? Qhbm af Artificial fill Qhty Tpu Qhay afbm af 1. California Geological Survey, 801 K st. MS 12-31, Sacramento, CA 95814 Qof Qhbm 30 Qhf af Tsvt 2. William Lettis & Associates, Inc., 1777 Botello Drive, Suite 262 Walnut Creek, CA 94596 Tsvm Tsvm alf Tsvm Tsvm alf Qhbm afbm Artificial fill placed over bay mud 80 Tsvt? Tsvm Qhbm Qls Qhay 80 Qls Tsvt Qhbm Qhbm Qhbm Artificial levee fill Qhf alf 35 45 Tsvt Tsvt Tsvm 40 Tsvm Tsvt Qhbm Qhf 20 Qls Qhbm Qha af Qhc Late Holocene to modern (<150 years) stream channel deposits in active, natural KJfm Franciscan Complex melange. -

Sonoma Creek Baylands Strategy - Executive Summary May 2020 Contact: [email protected]

Sonoma Creek Baylands Strategy - Executive Summary May 2020 Contact: [email protected] Introduction Prior to the 1850s, the Sonoma Creek baylands were a vast mosaic of tidal and seasonal wetlands. Fresh water, sediment, and nutrients were delivered from the upper watershed to mix with the tidal waters of San Pablo Bay, creating a small estuary teeming with life. Floods along Sonoma Creek and Schell Creek spread out in an alluvial fan in the region south of present-day State Route (SR) 121, creating distributary channels and depositing sediment. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Sonoma Creek baylands, along with 80 percent of wetlands around San Francisco Bay, were diked and drained for agriculture and other purposes. This created discrete parcels and simplified creek networks. Flow of water and sediment across the alluvial fans was blocked and confined to the creek channels. As a result, portions of Schellville and surrounding areas in southern Sonoma County are frequently flooded during relatively small winter storm events, when flows overtop the banks of Sonoma and Schell creeks, resulting in road closures at the junction of SR 121 and SR 12 that affect travel and public safety. Much of what used to be tidal marsh has been transformed into other habitat types including diked agricultural fields. Narrow strips of tidal marsh have developed adjacent to the tidal slough channels that run between the diked agricultural baylands. Development within the Sonoma Creek baylands continues despite the chronic flooding that is caused by filling and fragmentation of the floodplain. Flooding, and loss of habitat, species, and ecological function will increase with climate change-driven sea level rise and increased storm intensity. -

SONOMA VALLEY HISTORICAL HYDROLOGY MAPPING PROJECT, TASK 2.4.B: FINAL REPORT

Sonoma Valley Historical Hydrology Mapping Project Phase I FINAL REPORT Task 2.4b Arthur Dawson, Baseline Consulting Alex Young, Sonoma Ecology Center Rebecca Lawton Consulting Funded by the Sonoma County Water Agency November 2016 Prepared by: Baseline Consulting, 13750 Arnold Drive, P.O. Box 207, Glen Ellen, CA 95442 Sonoma Ecology Center, P.O. Box 1486, Eldridge, CA 95431 Rebecca Lawton Consulting, P.O. Box 654, Vineburg, CA 95687 BASELINE CONSULTING, SONOMA ECOLOGY CENTER, REBECCA LAWTON CONSULTING 2 CONTENTS OVERVIEW 3 METHODS 5 RESULTS 17 DISCUSSION 22 Comparison of Modern & Historical Conditions 24 RECOMMENDATIONS 27 BIBLIOGRAPHY 30 FIGURES 1. Project Area, Sonoma Valley Watershed, Sonoma County, California 4 2. Definition of Terms and Assumptions 6 3. Wetland Designations Used in this Study 10 4. Certainty Level Standards 14 5. Data Limitations and Temporal Context 15 6. Dates of Sources Used in this Study in Relation to Long-Term Rainfall 16 7. Estimated Pre-Settlement Freshwater Channels and Wetlands 18 8. Estimated Pre-Settlement Freshwater Channels and Wetlands (LIDAR Basemap) 19 9. Estimated Pre-Settlement Freshwater Channels and Wetlands (USGS quads) 20 10. Certainty Levels for Presence of Features Mapped from Historical Sources 21 11. Average annual hydrographs for the historical watershed for Napa River 25 APPENDIXES A. Selected Historical Maps A1. Detail from O’Farrell’s 1848 Rancho Petaluma Map A-2 A2. Confluence of Agua Caliente and Sonoma Creeks in 1860 A-3 A3. Confluence of Agua Caliente and Sonoma Creeks in 1980 A-4 A4. Alternate Channels Occupied by Pythian, an Unnamed Creek, and Sonoma Creek A-5 B. -

Courage and Thoughtful Scholarship = Indigenous Archaeology Partnerships

FORUM COURAGE AND THOUGHTFUL SCHOLARSHIP = INDIGENOUS ARCHAEOLOGY PARTNERSHIPS Dale R. eroes Robert McGhee's recent lead-in American Antiquity article entitled Aboriginalism and Problems of Indigenous archaeology seems to emphasize the pitfalls that can occur in "indige nolls archaeology." Though the effort is l1ever easy, I would empha size an approach based on a 50/50 partnership between the archaeological scientist and the native people whose past we are attempting to study through our field alld research techniques. In northwestern North America, we have found this approach important in sharillg ownership of the scientist/tribal effort, and, equally important, in adding highly significant (scientif ically) cullUral knowledge ofTribal members through their ongoing cultural transmission-a concept basic to our explana tion in the field of archaeology and anthropology. Our work with ancient basketry and other wood and fiber artifacts from waterlogged Northwest Coast sites demonstrates millennia ofcultl/ral cOlltinuity, often including reg ionally distinctive, highly guarded cultural styles or techniques that tribal members continue to use. A 50/50 partnership means, and allows, joint ownership that can only expand the scientific description and the cultural explanation through an Indigenous archaeology approach. El artIculo reciente de Robert McGhee en la revista American Antiquity, titulado: Aborigenismo y los problemas de la Arque ologia Indigenista, pC/recen enfatizar las dificultades que pueden ocurrir en la "arqueologfa indigenista -

Archaeology and Development / Peter G. Gould

Theme01: Archaeology and Development / Peter G. Gould Poster T01-91P / Mohammed El Khalili / Managing Change in an ever-Changing Archeological Landscape: Safeguard the Natural and Cultural Landscape of Jarash T01-92P / Wai Man Raymond Lee / Archaeology and Development: a Case Study under the Context of Hong Kong T01A / RY103 / SS5,SS6 T01A01 / Emmanuel Ndiema / Engaging Communities in Cultural Heritage Conservation: Perspectives from Kakapel, Western Kenya T01A02 / Paul Edward Montgomery / Branding Barbarians: The Development of Renewable Archaeotourism Destinations to Re-Present Marginalized Cultures of the Past T01A03 / Selvakumar Veerasamy / Historical Sites and Monuments and Community Development: Practical Issues and ground realities T01A04 / Yoshitaka SASAKI / Sustainable Utilization Approach to Cultural Heritage and the Benefits for Tourists and Local Communities: The Case of Akita Fortification, Akita prefecture, Japan. T01A05 / Angela Kabiru / Sustainable Development and Tourism: Issues and Challenges in Lamu old Town T01A06 / Chulani Rambukwella / ENDANGERED ARCHAEOLOGICAL LANDSCAPE OF THE WORLD HERITAGE CITY OF KANDY AND ITS SUBURBS IN SRI LANKA T01A07 / chandima bogahawatta / Sigiriya: World’s Oldest Living Heritage and Multi Tourist Attraction T01A08 / Shahnaj Husne Jahan Leena / Sustainable Development through Archaeological Heritage Management and Eco-Tourism at Bhitargarh in Bangladesh T01A09 / OLALEKAN AKINADE / IGBO UKWU ARCHAEOLOGICAL HERITAGE AS A BOOST TO NIGERIAN CULTURAL HERITAGE OLALEKAN AJAO AKINADE, [email protected] -

San Francisco Bay Plan

San Francisco Bay Plan San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission In memory of Senator J. Eugene McAteer, a leader in efforts to plan for the conservation of San Francisco Bay and the development of its shoreline. Photo Credits: Michael Bry: Inside front cover, facing Part I, facing Part II Richard Persoff: Facing Part III Rondal Partridge: Facing Part V, Inside back cover Mike Schweizer: Page 34 Port of Oakland: Page 11 Port of San Francisco: Page 68 Commission Staff: Facing Part IV, Page 59 Map Source: Tidal features, salt ponds, and other diked areas, derived from the EcoAtlas Version 1.0bc, 1996, San Francisco Estuary Institute. STATE OF CALIFORNIA GRAY DAVIS, Governor SAN FRANCISCO BAY CONSERVATION AND DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION 50 CALIFORNIA STREET, SUITE 2600 SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA 94111 PHONE: (415) 352-3600 January 2008 To the Citizens of the San Francisco Bay Region and Friends of San Francisco Bay Everywhere: The San Francisco Bay Plan was completed and adopted by the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission in 1968 and submitted to the California Legislature and Governor in January 1969. The Bay Plan was prepared by the Commission over a three-year period pursuant to the McAteer-Petris Act of 1965 which established the Commission as a temporary agency to prepare an enforceable plan to guide the future protection and use of San Francisco Bay and its shoreline. In 1969, the Legislature acted upon the Commission’s recommendations in the Bay Plan and revised the McAteer-Petris Act by designating the Commission as the agency responsible for maintaining and carrying out the provisions of the Act and the Bay Plan for the protection of the Bay and its great natural resources and the development of the Bay and shore- line to their highest potential with a minimum of Bay fill. -

Tidewater Park Trail, Oakland, CA LWCF Funding Assistance: $183,000

Land and Water Conservation Fund National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Tidewater Park Trail, Oakland, CA LWCF Funding Assistance: $183,000 Completing the Bay Trail in Oakland Located near the Oakland International Airport and part of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Regional Shoreline, Tidewater Park is a significant shoreline access point and open space along the Alameda waterfront, fea- turing spectacular views of San Leandro Bay. Recent Land and Water Conservation Fund improvements include completion of about half a mile of the multi-use San Francisco Bay Trail, restrooms, 1.4 acres of turf with trees and irrigation and picnic areas. “The Oakland waterfront and the Bay Trail are recreational resources for the entire Bay Area and serve a greater- than-local population, while providing Oakland residents with a new recre- ational resource.” California Coastal Conservancy www.nps.gov/lwcf Land and Water Conservation Fund National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Tolay Lake Acquisition, Sonoma County, CA LWCF Funding Assistance: $202,980 Protecting Sonoma Baylands for a New Regional Park “County officials have learned through bitter experience that park sites are The proposed Tolay Lake Regional Park, a project of Sonoma County, is an effort hard to find…. Which means the time is to provide hiking, horseback riding, bird- now. This rare opportunity needs to be watching, picnicking and other recreation embraced so that 10 years or 100 years activities while protecting pristine farm from now, people will be able to stand and grasslands, critical habitat for threat- on that ridge and be inspired by what ened and endangered species, significant they see.” prehistoric and archaeological sites.