Prairie Mountain Health CHA 2019 7-1-2020 Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visitor Guide

VISITOR GUIDE 2017 Contents 3 Celebrate Canada 150 4 Welcome 5 Calendar of events 6 The Franklin Expedition 6 Artists in Residence 7 Visitor Centre 8-9 Guided experiences 10 Indigenous People of Riding Mountain 11 Bison and Wildlife 12-13 Camping 14-15 Trails 16-17 Riding Mountain National Park map 18 Wasagaming map 19 Clear Lake map 20-21 Welcome to Wasagaming 22-23 History of Riding Mountain 24 Clear Lake Country 25-27 The Shops at Clear Lake 28 Friends of Riding Mountain National Park 29 Photo Contest 30-33 Visitor Information 34 Winter in Riding Mountain 35 Contact Information Discover and Xplore the park Get your Xplorer booklet at the Visitor Centre and begin your journey through Riding Mountain. Best suited for 6 to 11-year-olds. 2 RidingNP RidingNP Parks Canada Discovery Pass The Discovery Pass provides unlimited opportunities to enjoy over 100 National Parks, National Historic Sites, and National Marine Conservation Areas across Canada. Parks Canada is happy to offer free admission for all visitors to all places operated by Parks Canada in 2017 to celebrate the 150th anniversary of Confederation. For more information regarding the Parks Canada Discovery Pass, please visit pc.gc.ca/eng/ar-sr/lpac-ppri/ced-ndp.aspx. Join the Celebration with Parks Canada! 2017 marks the 150th anniversary of Canadian Confederation and we invite you to celebrate with Parks Canada! Take advantage of free admission to national parks, national historic sites and national marine conservation areas for the entire year. Get curious about Canada’s unique natural treasures, hear stories about Indigenous cultures, learn to camp and paddle and celebrate the centennial of Canada’s national historic sites with us. -

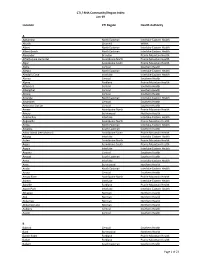

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19

CTI / RHA Community/Region Index Jan-19 Location CTI Region Health Authority A Aghaming North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Akudik Churchill WRHA Albert North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Albert Beach North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Alexander Brandon Prairie Mountain Health Alfretta (see Hamiota) Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Algar Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Alpha Central Southern Health Allegra North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Almdal's Cove Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Alonsa Central Southern Health Alpine Parkland Prairie Mountain Health Altamont Central Southern Health Albergthal Central Southern Health Altona Central Southern Health Amanda North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Amaranth Central Southern Health Ambroise Station Central Southern Health Ameer Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Amery Burntwood Northern Health Anama Bay Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Angusville Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arbakka South Eastman Southern Health Arbor Island (see Morton) Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Arborg Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arden Assiniboine North Prairie Mountain Health Argue Assiniboine South Prairie Mountain Health Argyle Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Arizona Central Southern Health Amaud South Eastman Southern Health Ames Interlake Interlake-Eastern Health Amot Burntwood Northern Health Anola North Eastman Interlake-Eastern Health Arona Central Southern Health Arrow River Assiniboine -

Variations in Resource Use and Costs of Hospital Care in Manitoba

VARIATIONS IN RESOURCE USE AND COSTS OF HOSPITAL CARE IN MANITOBA Authors: Nathan Nickel, PhD Greg Finlayson, PhD Randy Fransoo, PhD Roxana Dragan, MA Charles Burchill, MSc Okechukwu Ekuma, MSc Tamara Thomson, MSc Leanne Rajotte, BComms(Hons) Joshua Ginter, MA Ruth-Ann Soodeen, MSc Susan Burchill, BMus Fall 2017 Manitoba Centre for Health Policy Max Rady College of Medicine Rady Faculty of Health Sciences University of Manitoba This report is produced and published by the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (MCHP). It is also available in PDF format on our website at: http://mchp-appserv.cpe.umanitoba.ca/deliverablesList.html Information concerning this report or any other report produced by MCHP can be obtained by contacting: Manitoba Centre for Health Policy Rady Faculty of Health Sciences Max Rady College of Medicine, University of Manitoba 4th Floor, Room 408 727 McDermot Avenue Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada R3E 3P5 Email: [email protected] Phone: (204) 789-3819 Fax: (204) 789-3910 How to cite this report: Nickel N, Finlayson G, Fransoo R, Dragan R, Burchill C, Ekuma O, Thomson T, Rajotte L, Ginter J, Soodeen RA, Burchill S. Variations in Resource Use and Costs of Hospital Care in Manitoba. Winnipeg, MB. Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, Fall 2017. Legal Deposit: Manitoba Legislative Library National Library of Canada ISBN 978-1-896489-86-5 ©Manitoba Health This report may be reproduced, in whole or in part, provided the source is cited. 1st printing (Fall 2017) This report was prepared at the request of Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living (MHSAL) as part of the contract between the University of Manitoba and MHSAL. -

Directory – Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba

Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba A directory of groups and programs organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis people Community Development Corporation Manual I 1 INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People Compiled, edited and printed by Indigenous Inclusion Directorate Manitoba Education and Training and Indigenous Relations Manitoba Indigenous and Municipal Relations ________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The directory of Indigenous organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to help people locate appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Indigenous organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown from 16 pages in the first edition to more than 100 pages in the current edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Indigenous cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present accurate and up-to-date listings, with fax numbers, email addresses and websites included whenever possible. If you see any errors or omissions, or if you have updated information on any of the programs and services included in this directory, please call, fax or write to the Indigenous Relations, using the contact information on the -

Regional Stakeholders in Resource Development Or Protection of Human Health

REGIONAL STAKEHOLDERS IN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT OR PROTECTION OF HUMAN HEALTH In this section: First Nations and First Nations Organizations ...................................................... 1 Tribal Council Environmental Health Officers (EHO’s) ......................................... 8 Government Agencies with Roles in Human Health .......................................... 10 Health Canada Environmental Health Officers – Manitoba Region .................... 14 Manitoba Government Departments and Branches .......................................... 16 Industrial Permits and Licensing ........................................................................ 16 Active Large Industrial and Commercial Companies by Sector........................... 23 Agricultural Organizations ................................................................................ 31 Workplace Safety .............................................................................................. 39 Governmental and Non-Governmental Environmental Organizations ............... 41 First Nations and First Nations Organizations 1 | P a g e REGIONAL STAKEHOLDERS FIRST NATIONS AND FIRST NATIONS ORGANIZATIONS Berens River First Nation Box 343, Berens River, MB R0B 0A0 Phone: 204-382-2265 Birdtail Sioux First Nation Box 131, Beulah, MB R0H 0B0 Phone: 204-568-4545 Black River First Nation Box 220, O’Hanley, MB R0E 1K0 Phone: 204-367-8089 Bloodvein First Nation General Delivery, Bloodvein, MB R0C 0J0 Phone: 204-395-2161 Brochet (Barrens Land) First Nation General Delivery, -

Gambler First Nation Communicable Disease Emergency Plan

Gambler First Nation Communicable Disease Emergency Plan (Appendix “F” Community Emergency Response Plan) 2021 Gambler First Nation would like to thank the Ebb and Flow First Nation Health Authority Inc. for graciously sharing their plan template with our community. 0 Table of Contents SECTION 1: OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................................ 3 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 3 1.2 Purpose and Scope ....................................................................................................................... 3 1.3 Plan Review/Maintenance/Distribution ..................................................................................... 4 1.4 Training and Exercises .................................................................................................................. 5 1.5 Mutual Aid Agreements ............................................................................................................... 5 1.6 Context for a Communicable Disease Emergency ....................................................................... 6 1.7 Responsibilities ............................................................................................................................. 6 1.7.1 Community Level Responsibilities ........................................................................................... 6 1.7.2 Provincial -

Prairie Mountain Health

Manitoba Health, Seniors and Active Living Population Report - June 1, 2020 Population of Prairie Mountain Health June 1, 2020 Manitoba RHAs -- Prairie Mountain Health Prairie Mountain Health (c) Prov. of Manitoba, 2021 Cartography by: MHSAL, Information Management & Analytics Last update: April. 2021 Manitoba Health, Seniors, and Active Living Population Report, June 1, 2020 Prairie Mountain Health Region District Gender Under 1 1 - 4 5 - 9 10 - 14 15 - 19 20 - 24 25 - 29 30 - 34 35 - 39 40 - 44 45 - 49 50 - 54 55 - 59 60 - 64 65 - 69 70 - 74 75 + Total PMH Brandon Zone Brandon Downtown F 78 306 391 298 378 499 534 490 453 419 375 326 338 285 227 224 580 6,201 M 68 322 403 334 361 473 559 537 523 432 391 344 349 283 207 157 284 6,027 Brandon East End F 49 189 235 240 187 217 266 300 266 241 198 169 207 164 118 121 407 3,574 M 42 180 255 209 204 230 279 282 299 246 218 171 200 156 115 84 226 3,396 Brandon North Hill F 44 150 204 234 217 233 282 272 265 241 228 210 290 254 269 235 303 3,931 M 40 175 251 236 208 214 248 266 236 216 238 210 228 240 218 181 285 3,690 Brandon South End F 70 284 343 313 289 327 371 434 435 370 333 308 344 330 269 243 355 5,418 M 66 300 390 343 324 354 353 366 431 385 342 307 306 277 259 199 276 5,278 Brandon West End F 78 440 566 570 517 585 642 686 675 659 557 466 542 487 464 390 756 9,080 M 93 453 579 593 537 547 541 647 644 592 579 458 482 449 401 344 524 8,463 F 319 1,369 1,739 1,655 1,588 1,861 2,095 2,182 2,094 1,930 1,691 1,479 1,721 1,520 1,347 1,213 2,401 28,204 M 309 1,430 1,878 1,715 1,634 1,818 -

02:00 PM 2020-10-14 On

1 1 RETURN BIDS TO: Title - Sujet RETOURNER LES SOUMISSIONS À: Fire, Safety and Rescue Equi (RFSO) Bid Receiving - PWGSC / Réception des soumissions - Solicitation No. - N° de l'invitation Date TPSGC E60HN-20FSRE/B 2020-10-02 11 Laurier St. / 11, rue Laurier Client Reference No. - N° de référence du client Amendment No. - N° modif. Place du Portage, Phase III E60HN-20FSRE 003 Core 0B2 / Noyau 0B2 Gatineau, Québec K1A 0S5 File No. - N° de dossier CCC No./N° CCC - FMS No./N° VME Bid Fax: (819) 997-9776 hn336.E60HN-20FSRE GETS Reference No. - N° de référence de SEAG PW-$$HN-336-79041 Date of Original Request for Standing Offer 2020-08-31 Revision to a Request for a Standing Offer Date de la demande de l'offre à commandes originale Révision à une demande d'offre à commandes Solicitation Closes - L'invitation prend fin Time Zone Fuseau horaire National Master Standing Offer (NMSO) at - à 02:00 PM on - le 2020-10-14 Eastern Daylight Offre à commandes principale et nationale (OCPN) Saving Time EDT Address Enquiries to: - Adresser toutes questions à: Buyer Id - Id de l'acheteur Bisson(hn336), Phillipe hn336 The referenced document is hereby revised; unless otherwise indicated, all other terms and conditions of Telephone No. - N° de téléphone FAX No. - N° de FAX the Offer remain the same. (613) 295-8641 ( ) ( ) - Delivery Required - Livraison exigée Ce document est par la présente révisé; sauf indication contraire, les modalités de l'offre demeurent les mêmes. Destination - of Goods, Services, and Construction: Destination - des biens, services et construction: Comments - Commentaires 140 O'Connor St., Ottawa, ON Canada K1A 0R5 Vendor/Firm Name and Address Security - Sécurité Raison sociale et adresse du This revision does not change the security requirements of the Offer. -

5 Traditional Land and Resource Use

CA PDF Page 1 of 92 Energy East Project Part B: Saskatchewan and Manitoba Volume 16: Socio-Economic Effects Assessment Section 5: Traditional Land and Resource Use This section was not updated in 2015, so it contains figures and text descriptions that refer to the October 2014 Project design. However, the analysis of effects is still valid. This TLRU assessment is supported by Volume 25, which contains information gathered through TLRU studies completed by participating Aboriginal groups, oral traditional evidence and TLRU-specific results of Energy East’s aboriginal engagement Program from April 19, 2014 to December 31, 2015. The list of First Nation and Métis communities and organizations engaged and reported on is undergoing constant revision throughout the discussions between Energy East and potentially affected Aboriginal groups. Information provided through these means relates to Project effects and cumulative effects on TLRU, and recommendations for mitigating effects, as identified by participating Aboriginal groups. Volume 25 for Prairies region provides important supporting information for this section; Volume 25 reviews additional TRLU information identifies proposed measures to mitigate potential effects of the Project on TRLU features, activities, or sites identified, as appropriate. The TLRU information provided in Volume 25 reflects Project design changes that occurred in 2015. 5 TRADITIONAL LAND AND RESOURCE USE Traditional land and resource use (TLRU)1 was selected as a valued component (VC) due to the potential for the Project to affect traditional activities, sites and resources identified by Aboriginal communities. Project Aboriginal engagement activities and the review of existing literature (see Appendix 5A.2) confirmed the potential for Project effects on TLRU. -

Birtle Transmission Project Environmental Assessment Report

5.0 Environmental and socio-economic setting 5.1 Overview This chapter provides an overview of the physical, ecological (aquatic and terrestrial), and socio-economic environment with respect to the Project. It begins with a summary of the regional setting that discusses historic, present and potential future conditions for the region. The physical environment section then provides information on the existing: • Atmospheric conditions(climate, noise and air quality); • Surface water; • Geology and hydrogeology; and • Terrain and soils. This is followed by a section on the existing ecological environment, which discusses: • Fish habitat and resources; • Vegetation; • Terrestrial invertebrates; • Reptiles; • Amphibians; • Mammals; and • Birds. The socio-economic environment section then provides information on: • Population; • Infrastructure and services; • Employment and economy; • Property and residential development; • Agriculture; • Other commercial resource use; • Recreation and tourism; • Health; 5-1 • Traditional land and resource use; and • Heritage resources. The information in this chapter provides the basis of this environmental assessment. Additional information regarding the existing physical and ecological environment is provided in Appendix D, and additional information regarding the socioeconomic environment is provided in Appendix E. 5.2 Regional setting summary 5.2.1 Historic conditions The Project is located in the Interior Plains Physiographic Region, which covers southwest Manitoba, southern Saskatchewan and most of Alberta (Weir 2012). The generally low relief and soils in the area were formed through retreating glaciers and Lake Agassiz, and are generally very fertile. Relief in the region is primarily as a result of large rivers such as the Assiniboine and its tributaries, which have eroded deep valleys and ravines in some areas. -

District Profile Whitemud

DISTRICT PROFILE WHITEMUD LOCATION AND DEMOGRAPHICS LOCATION The Whitemud district is located in the South Zone on the east side of the PMH region. The district extends from the southeast corner of Riding Mountain National Park in the north to the Town of Carberry in the south. 1 2 2 DEMOGRAPHICS Population : 11,490 Land Area: 3,913 km Density: 2.94 persons/km FACILITIES Neepawa Health Centre, Neepawa PCH (Country Meadows), and Carberry Health Centre and PCH. COMMUNITY HEALTH Public Health, Home Care, Mental Health, Primary Health Care, Emergency SERVICES Medical Services DID YOU KNOW? Whitemud has the lowest prevalence of Total Respiratory Morbidity in Prairie Mountain Health Whitemud has the lowest prevalence of Substance Abuse in PMH ! Less than 50% of new depression patients in Whitemud had appropriate antidepressant follow-up care ! Whitemud has the second lowest rate of Appropriate Asthma Medication Use in the South Zone amongst those diagnosed with asthma Over 25% of Whitemud seniors (age 75+) living in the community (not in a personal care home) use Benzodiazepines SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC INDICATORS 5.5 dependents age LIFE DEPENDENCY 0-14 and 65+ for every 2 1 EXPECTANCY 83.2 years 78.0 years RATIO 10 of working age 15-64 Tenant: MEDIAN HOUSING 15.7% < 29.1% (PMH) HOUSEHOLD $53,867 > $50,888 3 3 AFFORDABILITY Owner: INCOME (PMH) 10.4% > 9.9% (PMH) 20% > 19% (PMH) EDUCATION population aged 25- UNEMPLOYMENT 3 3 LEVEL 64 without a High RATE 2.5% < 5.9% (PMH) School Diploma NOTES 1 Manitoba Health Population Reports, 2013 2 Manitoba Centre for Health Policy RHA Indicators Atlas, 2013 3 2011 Census. -

Pursuant to Rule 42 of the October 1, 2015 4

SCT File No.: SCT-4002-15 SPECIFIC CLAIMS TRIBUNAL BETWEEN: GAMBLER FIRST NATION also known as GAMBLERS FIRST NATION Claimant v. HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN IN RIGHT OF CANADA As represented by the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Respondent RESPONSE Pursuant to Rule 42 of the Specific Claims Tribunal Rules ofPractice a11d Procedure This Response is filed under the provisions of the Specific Claims Tribunal Act and the Specific Claims Tribunal Rules ofPractice and Procedure. TO: Gambler First Nation As represented by: Stephen M. Pillipow TheW Law Group Barristers and Solicitors 300-110, 21 51 Street East Saskatoon, SK S7K 086 Telephone: (306) 244-2242 Facsimile: (306) 652-0332 E-mail: spi11ipow@wlaw£roup.com Overview I. The Gambler First Nation, also known as the Gamblers First Nation (the "Claimant") alleges a surrender of a portion of Indian Reserve 63 ("IR 63") in 1898 was improperly done and that there was an unlawful lease or disposition of those reserve lands. The contested surrender in this claim is one of three occurring between 1881 and 1898. They arise in a context of the movement of interrelated or overlapping groups of Treaty 4 signatories between several reserve locations in this period. In respect of the 1898 surrender directly in issue in the present claim, the Claimant claims that the Crown incurred a legal obligation and must now compensate the Claimant for the lands taken. The Crown denies any outstanding lawful obligation is owed to the Claimant. The Crown says that in assessing the claim, the Tribunal will have to consider whether at the material time, the Claimant should be considered to be part of Waywayseecappo First Nation ("Waywayseecappo"), or regarded as a separate band.